Youth on the Prow, and Pleasure at the Helm

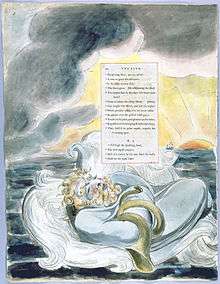

Youth on the Prow, and Pleasure at the Helm (also known as Fair Laughs the Morn and Youth and Pleasure) is an oil painting on canvas by English artist William Etty, first exhibited in 1832 and currently in Tate Britain. Etty had been planning the painting since 1818–19, and an early version was exhibited in 1822. The piece was inspired by a metaphor in Thomas Gray's poem The Bard in which the apparently bright start to the notorious misrule of Richard II of England was compared to a gilded ship whose occupants are unaware of an approaching storm. Etty chose to illustrate Gray's lines literally, depicting a golden boat filled with and surrounded by nude and near-nude figures.

Etty felt that his approach to the work illustrated a moral warning about the pursuit of pleasure, but his approach was not entirely successful. The Bard was about a supposed curse on the House of Plantagenet placed by a Welsh bard following Edward I of England's attempts to eradicate Welsh culture, and critics felt that Etty had somewhat misunderstood the point of Gray's poem. Some reviewers greatly praised the piece, and in particular Etty's technical abilities, but audiences of the time found it hard to understand the purpose of Etty's painting, and his use of nude figures led some critics to consider the work tasteless and offensive.

The painting was bought in 1832 by Robert Vernon to form part of his collection of British art. Vernon donated his collection, including Youth on the Prow, and Pleasure at the Helm, to the National Gallery in 1847, which, in turn, transferred it to the Tate Gallery in 1949. It remains one of Etty's best-known works, and formed part of major exhibitions at Tate Britain in 2001–02 and at the York Art Gallery in 2011–12.

Background

William Etty, the seventh son of a York baker and miller,[2] had been an apprentice printer in Hull.[3] On completing his seven-year apprenticeship at the age of 18 he moved to London "with a few pieces of chalk crayons",[4] and the intention of becoming a history painter in the tradition of the Old Masters.[5] He enrolled in the Schools of the Royal Academy of Arts, studying under renowned portrait painter Thomas Lawrence.[4] He submitted numerous paintings to the Royal Academy over the following decade, all of which were either rejected or received little attention when exhibited.[6]

In 1821 Etty's The Arrival of Cleopatra in Cilicia (also known as The Triumph of Cleopatra) was a critical success.[6] The painting featured nude figures, and over the following years Etty painted further nudes in biblical, literary and mythological settings.[7] All but one of the 15 paintings Etty exhibited in the 1820s included at least one nude figure.[8]

While some nudes existed in private collections, England had no tradition of nude painting and the display and distribution of nude material to the public had been suppressed since the 1787 Proclamation for the Discouragement of Vice.[9] Etty was the first British artist to specialise in the nude,[10] and the reaction of the lower classes to these paintings caused concern throughout the 19th century.[11] Although his portraits of male nudes were generally well received,[upper-alpha 1] many critics condemned his repeated depictions of female nudity as indecent.[7][8]

Composition

Fair laughs the morn, and soft the zephyr blows,

While proudly riding o'er the azure realm,

In gallant trim, the gilded vessel goes,

Youth on the prow and Pleasure at the helm,

Unmindful of the sweeping whirlwind's sway,

That, hushed in grim repose, expects his evening prey.

Lines from The Bard which accompanied Youth and Pleasure when originally exhibited.[13]

Youth on the Prow, and Pleasure at the Helm was inspired by a passage in Thomas Gray's poem The Bard.[14] The theme of The Bard was the English king Edward I's conquest of Wales, and a curse placed by a Welsh bard upon Edward's descendants after he ordered the execution of all bards and the eradication of Welsh culture.[14] Etty used a passage Gray intended to symbolise the seemingly bright start to the disastrous reign of Edward's great-great-grandson Richard II.[15]

Etty chose to illustrate Gray's words literally, creating what has been described as "a poetic romance".[10] Youth and Pleasure depicts a small gilded boat. Above the boat, a nude figure representing Zephyr blows on the sails. Another nude representing Pleasure lies on a large bouquet of flowers, loosely holding the helm of the boat and allowing Zephyr's breeze to guide it. A nude child blows bubbles, which another nude on the prow of the ship, representing Youth, reaches to catch. Naiads, again nude, swim around and clamber on the boat.[14] Although the seas are calm, a "sweeping whirlwind" is forming on the horizon, with a demonic figure within the storm clouds.[14][16] (Deterioration and restoration means this demonic figure is now barely visible.[14]) The intertwined limbs of the participants were intended to evoke the sensation of transient and passing pleasure, and to express the themes of female sexual appetites entrapping innocent youth,[17] and the sexual power women hold over men.[10]

Etty said of his approach to the text that he was hoping to create "a general allegory of Human Life, its empty vain pleasures—if not founded on the laws of Him who is the Rock of Ages."[18] While Etty felt that the work conveyed a clear moral warning about the pursuit of pleasure, this lesson was largely lost upon its audiences.[10]

When Etty exhibited the completed painting at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1832,[19] it was shown untitled,[20] with the relevant six lines from The Bard attached;[14] writers at the time sometimes referred to it by its incipit of Fair Laughs the Morn.[20][upper-alpha 2] By the time of Etty's death in 1849, it had acquired its present title of Youth on the Prow, and Pleasure at the Helm.[21]

Versions

The final version of Youth and Pleasure was painted between 1830 and 1832,[22] but Etty had been contemplating a painting on the theme since 1818–19.[23] In 1822 he had exhibited an early version at the British Institution titled A Sketch from One of Gray's Odes (Youth on the Prow);[24][25] in this version the group of figures on the prow is reversed, and the swimmers around the boat are absent.[23] Another rough version of the painting also survives, similar to the 1832 version but again with the figures on the prow reversed.[26] This version was exhibited at a retrospective of Etty's work at the Society of Arts in 1849; it is dated 1848 but this is likely to be a misprint of 1828, making it a preliminary study for the 1832 painting.[26]

Although it received little notice when first exhibited, the 1822 version provoked a strong reaction from The Times:

We take this opportunity of advising Mr. Etty, who got some reputation for painting "Cleopatra's Galley", not to be seduced into a style which can gratify only the most vicious taste. Naked figures, when painted with the purity of Raphael, may be endured: but nakedness without purity is offensive and indecent, and on Mr. Etty's canvass is mere dirty flesh. Mr. Howard,[upper-alpha 3] whose poetical subjects sometimes require naked figures, never disgusts the eye or mind. Let Mr. Etty strive to acquire a taste equally pure: he should know, that just delicate taste and pure moral sense are synonymous terms.— The Times, 29 January 1822[28]

An oil sketch attributed to Etty, given to York Art Gallery in 1952 by Judith Hare, Countess of Listowel and entitled Three Female Nudes, is possibly a preliminary study by Etty for Youth and Pleasure, or a copy by a student of the three central figures.[26] Art historian Sarah Burnage considers both possibilities unlikely, as neither the arrangement of figures, the subject matter or the sea serpent approaching the group appear to relate to the completed Youth and Pleasure, and considers it more likely to be a preliminary sketch for a now-unknown work.[29]

Reception

Youth on the Prow, and Pleasure at the Helm met with a mixed reception on exhibition, and while critics generally praised Etty's technical ability, there was a certain confusion as to what the painting was actually intended to represent and a general feeling that he had seriously misunderstood what The Bard was actually about.[14] The Library of the Fine Arts felt "in classical design, anatomical drawing, elegance of attitude, fineness of form, and gracefulness of grouping, no doubt Mr. Etty has no superior", and while "the representation of the ideas in the lines quoted [from The Bard] are beautifully and accurately expressed upon the canvas" they considered "the ulterior reference of the poet [to the destruction of Welsh culture and the decline of the House of Plantagenet] was entirely lost sight of, and that, if this be the nearest that Art can approach in conveying to the eye the happy exemplification of the subject which Gray intended, we fear we must give up the contest upon the merits of poetry and painting."[30] Similar concerns were raised in The Times, which observed that it was "Full of beauty, rich in colouring, boldly and accurately drawn, and composed with a most graceful fancy; but the meaning of it, if it has any meaning, no man can tell", pointing out that although it was intended to illustrate Gray it "would represent almost as well any other poet's fancies."[20] The Examiner, meanwhile, took issue with the cramped and overladen boat, pointing out that the characters "if not exactly jammed together like figs in a basket, are sadly constrained for want of room", and also complained that the boat would not in reality "float half the weight which is made to press upon it."[14]

Other reviewers were kinder; The Gentleman's Magazine praised Etty's ability to capture "the beauty of the proportion of the antique", noting that in the central figures "there is far more of classicality than is to be seen in almost any modern picture", and considered the overall composition "a most fortunate combination of the ideality of Poetry and the reality of Nature".[16] The Athenæum considered it "a poetic picture from a very poetic passage", praising Etty for "telling a story which is very difficult to tell with the pencil".[31]

The greatest criticism of Youth and Pleasure came from The Morning Chronicle, a newspaper which had long disliked Etty's female nudes.[32] It complained "no decent family can hang such sights against their wall",[33] and condemned the painting as an "indulgence of what we once hoped a classical, but which are now convinced, is a lascivious mind", commenting "the course of [Etty's] studies should run in a purer channel, and that he should not persist, with an unhallowed fancy, to pursue Nature to her holy recesses. He is a laborious draughtsman, and a beautiful colourist; but he has not taste or chastity of mind enough to venture on the naked truth." The reviewer added "we fear that Mr. E will never turn from his wicked ways, and make himself fit for decent company."[32]

Legacy

Youth on the Prow, and Pleasure at the Helm was purchased at the time of its exhibition by Robert Vernon for his important collection of British art.[10][23] (The price Vernon paid for Youth and Pleasure is not recorded, although Etty's cashbook records a partial payment of £250—about £21,000 in 2016 terms[34]—so it is likely to have been a substantial sum.[26]) Vernon later purchased John Constable's The Valley Farm, planning to hang it in the place then occupied by Youth and Pleasure. This decision caused Constable to comment "My picture is to go into the place—where Etty's "Bumboat" is at present—his picture with its precious freight is to be brought down nearer to the nose."[10][upper-alpha 4] Vernon presented his collection to the nation in 1847, and his 157 paintings, including Youth and Pleasure, entered the National Gallery.[36]

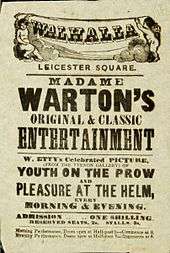

When Samuel Carter Hall was choosing works to illustrate his newly launched The Art Journal, he considered it important to promote new British artists, even if it meant illustrations which some readers considered pornographic or offensive. In 1849 Hall secured reproduction rights to the paintings Vernon had given to the nation and soon published and widely distributed an engraving of the painting under the title Youth and Pleasure,[35] describing it as "of the very highest class".[37]

Needled by repeated attacks from the press on his supposed indecency, poor taste and lack of creativity, Etty changed his approach after the response to Youth on the Prow, and Pleasure at the Helm.[38] He exhibited over 80 further paintings at the Royal Academy alone, and remained a prominent painter of nudes, but from this time made conscious efforts to reflect moral lessons.[39] He died in November 1849 and, while his work enjoyed a brief boom in popularity, interest in him declined over time, and by the end of the 19th century all of his paintings had fallen below their original prices.[40]

In 1949 the painting was transferred from the National Gallery to the Tate Gallery,[23] where as of 2015 it remains.[22] Although Youth and Pleasure is one of Etty's best-known paintings,[41] it remains controversial, and Dennis Farr's 1958 biography of Etty describes it as "singularly inept".[41] It was one of five works by Etty chosen for Tate Britain's landmark Exposed: The Victorian Nude exhibition in 2001–02,[10] and also formed part of a major retrospective of Etty's work at the York Art Gallery in 2011–12.[14]

Footnotes

- ↑ Etty's male nude portraits were primarily of mythological heroes and classical combat, genres in which the depiction of male nudity was considered acceptable in England.[12]

- ↑ Etty's 2007 biographer Leonard Robinson states that much of this verse was omitted, and the painting was captioned Fair laughs the Morn, and soft the Zephyr blows, Youth on the prow, and Pleasure at the helm, That hush'd in grim repose, expects his evening prey.[18] The original catalogue for the 1832 Summer Exhibition clearly indicates that all six lines accompanied the painting on its original exhibition.[13]

- ↑ Henry Howard, one of Etty's rivals in the field of history painting.[27]

- ↑ Art historians differ in their interpretation of Constable's reaction, and whether he was expressing surprise or pleasure that Vernon was moving Youth and Pleasure to a less prominent position to make way for The Valley Farm.[10][35]

References

Notes

- ↑ Burnage 2011b, p. 116.

- ↑ "William Etty". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8925. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Farr 1958, p. 5.

- 1 2 Burnage 2011a, p. 157.

- ↑ Smith 1996, p. 86.

- 1 2 Burnage 2011d, p. 31.

- 1 2 "About the artist". Manchester Art Gallery. Archived from the original on 2015-02-11. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- 1 2 Burnage 2011d, p. 32.

- ↑ Smith 2001b, p. 53.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Smith 2001a, p. 57.

- ↑ Smith 2001b, p. 55.

- ↑ Burnage 2011d, pp. 32–33.

- 1 2 The Exhibition of the Royal Academy: The Sixty Fourth. London: Royal Academy of Arts. 1832. p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Burnage 2011b, p. 128.

- ↑ Gray & Bradshaw 1891, p. 87.

- 1 2 "Fine Arts.—Royal Academy". The Gentleman's Magazine. London: J. B. Nichols and Son. 33 (6): 539. June 1832.

- ↑ Smith 2001a, p. 67.

- 1 2 Robinson 2007, p. 180.

- ↑ Burnage & Bertram 2011, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 "Royal Academy". The Times (14860). London. 24 May 1832. col F, p. 3.

- ↑ "Obituary.—William Etty, Esq, R.A.". The Gentleman's Magazine. London: John Bower Nichols and Son. 33 (1): 98. January 1850.

- 1 2 "William Etty – Youth on the Prow, and Pleasure at the Helm". Tate. May 2007. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Farr 1958, p. 158.

- ↑ Burnage & Bertram 2011, p. 22.

- ↑ Robinson 2007, p. 178.

- 1 2 3 4 Farr 1958, p. 159.

- ↑ Farr 1958, p. 31.

- ↑ "Lord Gwydyr". The Times (11466). London. 29 January 1822. col A, p. 3.

- ↑ Burnage 2011c, p. 215.

- ↑ "Exhibition of the Royal Academy". Library of the Fine Arts. London: M. Arnold. 4 (18): 57. July 1832.

- ↑ "Fine Arts; Exhibition at Somerset House". The Athenæum. London: J. Holmes (239): 340. 26 May 1832.

- 1 2 Burnage 2011d, p. 33.

- ↑ Burnage 2011b, p. 129.

- ↑ UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- 1 2 Robinson 2007, p. 181.

- ↑ Robinson 2007, p. 388.

- ↑ Smith 1996, p. 69.

- ↑ Burnage 2011d, p. 36.

- ↑ Burnage 2011d, p. 42.

- ↑ Robinson 2007, p. 440.

- 1 2 Farr 1958, p. 63.

Bibliography

- Burnage, Sarah (2011a). "Etty and the Masters". In Burnage, Sarah; Hallett, Mark; Turner, Laura. William Etty: Art & Controversy. London: Philip Wilson Publishers. pp. 154–97. ISBN 978-0-85667-701-4. OCLC 800599710.

- Burnage, Sarah (2011b). "History Painting and the Critics". In Burnage, Sarah; Hallett, Mark; Turner, Laura. William Etty: Art & Controversy. London: Philip Wilson Publishers. pp. 106–54. ISBN 978-0-85667-701-4. OCLC 800599710.

- Burnage, Sarah (2011c). "The Life Class". In Burnage, Sarah; Hallett, Mark; Turner, Laura. William Etty: Art & Controversy. London: Philip Wilson Publishers. pp. 198–227. ISBN 978-0-85667-701-4. OCLC 800599710.

- Burnage, Sarah (2011d). "Painting the Nude and 'Inflicting Divine Vengeance on the Wicked'". In Burnage, Sarah; Hallett, Mark; Turner, Laura. William Etty: Art & Controversy. London: Philip Wilson Publishers. pp. 31–46. ISBN 978-0-85667-701-4. OCLC 800599710.

- Burnage, Sarah; Bertram, Beatrice (2011). "Chronology". In Burnage, Sarah; Hallett, Mark; Turner, Laura. William Etty: Art & Controversy. London: Philip Wilson Publishers. pp. 20–30. ISBN 978-0-85667-701-4. OCLC 800599710.

- Farr, Dennis (1958). William Etty. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. OCLC 2470159.

- Gray, Thomas; Bradshaw, John (1891). Gray's Poems, with introduction and noted by John Bradshaw. London: Macmillan & Co. OCLC 779886823.

- Robinson, Leonard (2007). William Etty: The Life and Art. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2531-0. OCLC 751047871.

- Smith, Alison (2001a). Exposed: The Victorian Nude. London: Tate Publishing. ISBN 1-85437-372-2.

- Smith, Alison (2001b). "Private Pleasures?". In Bills, Mark. Art in the Age of Queen Victoria: A Wealth of Depictions. Bournemouth: Russell–Cotes Art Gallery and Museum. ISBN 0-905173-65-1.

- Smith, Alison (1996). The Victorian Nude. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4403-0.