Théodore Steeg

| Théodore Steeg | |

|---|---|

| |

| 100th Prime Minister of France | |

|

In office 13 December 1930 – 27 January 1931 | |

| Preceded by | André Tardieu |

| Succeeded by | Pierre Laval |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

19 December 1868 Libourne, Gironde, France |

| Died |

19 December 1950 (aged 82) Paris, France |

| Political party | Radical |

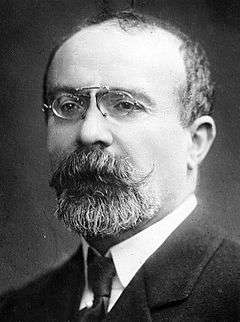

Théodore Steeg (French pronunciation: [teodɔʁ stɛɡ]) (19 December 1868 – 19 December 1950) was a lawyer and professor of philosophy who became Premier of the French Third Republic.

Steeg entered French politics in 1904 as a radical socialist, although his views were generally moderate. He was a Deputy of the Seine from 1904 to 1914 and Senator from 1914 to 1944. At different times he was Minister of Higher Education, Interior, Justice and Colonies. In the 1920s he was in charge of the colonial administrations first of Algeria and then of Morocco. He encouraged irrigation projects to provide land for French colons at a time of growing demands for political and economic rights from the indigenous people, accompanied by growing unrest. Steeg was briefly prime minister in 1930–1931.

Early years

Jules Joseph Théodore Steeg was born in Libourne, Gironde on 19 December 1868.[1] He was of German descent, and his political opponents would later attack him for this fact.[2] His father, Jules Steeg (1836–1898), was a Protestant pastor who became a journalist and then a radical deputy in the National Assembly.[lower-alpha 1][1] Théodore's mother was Anne-Marie Zoé Tuyès, born in 1840 in Orthez, Basses-Pyrénées.[1]

Théodore Steeg attended the college at Libourne and then studied at the Lycée Henri-IV in Paris. He was admitted to the University of Paris and the Faculty of Law, coming first there in 1887. He obtained the degrees of Bachelor of Laws and Bachelor of Arts in 1890.[3] He then began studies for the agrégation in Philosophy, in which he won first place in 1895.[4] On 25 October 1892 he married Ewaldine Bonet-Maury (born on 14 June 1872 in Dordrecht, Netherlands). She was the daughter of Gaston Bonet-Maury, a correspondent member of the Institute and a knight of the Legion of Honor, and the sister in law of the government architect Lecoeur. They were to have three daughters. The eldest, Juliette Isabelle, was born on 14 April 1894. She became a doctor and married a doctor.[1]

.jpg)

Théodore Steeg taught at the Alsatian school from 1892 to 1894, then was appointed professor of philosophy at the College of Vannes, and next taught at the College of Niort. In 1897 he co-founded the "People's Union" with Ferdinand Buisson, Maurice Bouchor, Émile Duclaux and Pauline Kergomard, and was secretary of the union for two years. After returning to Paris he taught philosophy at the Alsatian school and at the Lycée Charlemagne until 1904.[3]

Political career

Deputy (1904–1914)

Théodore Steeg was elected a deputy of the Seine in 1904.[5] He was aged 35.[6] He ran as a radical socialist in a by-election to replace Émile Dubois, who had died on 7 May 1904. Steeg was elected in the second round on 24 July 1904 for the second riding of the 14th arrondissement of Paris. As a new deputy, Steeg threw himself into a campaign for the protection and education of children. Steeg became a lawyer in Paris in 1905. He was re-elected with growing majorities in 1906 and 1910. In 1906 he was elected to the Budget Committee, responsible for Posts and Telegraphs. In 1907 he was appointed rapporteur on the Public Education budget.[3]

Théodore Steeg was appointed Minister of Public Instruction and Beaux-Arts in Ernest Monis's cabinet on 2 March 1911.[3] The Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre on 21 August 1911, and Steeg was forced to start an administrative inquiry into how such an important painting could have been stolen from such a major museum.[7] Steeg was a supporter of the Nouvelle Sorbonne movement with its insistence on basic republican principles. He rejected a petition to revise the Sorbonne reforms of 1902, to which the government was committed.[8]

On 14 January 1912 Steeg became Minister of Interior in Raymond Poincaré's government.[3] That year a Tunis congress of Alienists and Neurologists pointed out the lack of facilities for treating the insane in the colonies. Steeg worked with the Algerian governor-general, Charles Lutaud, to set up a planning commission to improve psychiatric care in the colony.[9] The committee filed its report in 1914. It recommended building an asylum at Blida, but World War I delayed implementation.[10]

On 21 January 1913 Steeg briefly resumed the post of Minister of Public Instruction and Beaux-Arts in Aristide Briand's third and fourth cabinets, holding office until 21 March 1913. He then resumed his seat in the Assembly, where he worked with Maurice Viollette to introduce humanitarian improvements to the Civil Code regarding illegitimate children.[3]

Senator (1914–1921)

On 12 March 1914 Théodore Steeg ran in a Senate election in the Seine department to replace Athanase Bassinet, who had died on 12 February 1914. He was elected on the second ballot. Steeg joined the Democratic Left. World War I (1914–1918) started in July 1914. In 1915 Steeg served on the Finance Committee and many special commissions. On 20 March 1917 he joined Alexandre Ribot's fifth cabinet as Minister of Public Instruction and Beaux-Arts, where he adopted the law of Wards of the Nation. Paul Painlevé succeeded Ribot on 12 September 1917, at a time when France was struggling for survival. Steeg was briefly Minister of the Interior in Painlevé's cabinet, leaving on 16 November 1917.[3]

In 1918 and 1919 Steeg returned to the ranks. He ran for re-election to the Senate on 11 January 1920 and won the first ballot. On 20 January 1920 Steeg was appointed Minister of Interior in Alexandre Millerand cabinet.[3] The right had won the election and the appointment of a Radical Socialist to this sensitive position was controversial.[11] Léon Daudet attacked Steeg, trying unsuccessfully to get Millerand to abandon Steeg's nomination. However, Millerand had appointed his friend in part to demonstrate his independence, in part due to his desire to form a "republican union" that rose above party lines, and stood firm.[12]

Steeg had to deal with a general strike launched by the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) on 1 May 1920 that first called out transport workers, then miners, seamen, dockers, metalworkers and other trades.[13] The government moved forcibly to end the strike. On 20 May 1920 Steeg said the government considered that deliberately trying to throw the country's economy into chaos was a criminal act. The strike was unsuccessful, and ended with the last workers returning on 28 May 1920.[14] Steeg retained his position as Minister of Interior in Georges Leygues's cabinet of 24 September 1920.[3] When Aristide Briand formed his cabinet on 16 January 1921, Steeg left the Ministry.[15] He was elected president of the new committee on general administration, departmental and communal.[3]

Algeria (1921–1925)

Steeg was appointed governor-general of Algeria on 28 July 1921 at a time when the colony was in crisis.[3] Muslim Algerians had fought for France in the trenches and now expected political rights.[16] The Jonnart Law of 4 February 1919 had granted less than the Muslims wanted, but more than the French colons could readily accept.[17] In April 1922 President Alexandre Millerand visited Algeria to calm the fears of the French colons about the growth in numbers of Muslim electors, and to assure them that France would continue to protect their interests. The prefect of Algiers did not want the influential Emir Khalid ibn Hashim (1875–1936) to present his position, but Steeg overrode him. Khaled told Millerand, "The inhabitants of Algeria without racial or religious distinction are equally children of France ... We come to solicit representation in the French Parliament."[18]

Steeg was able to reduce the tensions and initiate a stable period of economic growth.[3] As a Radical, Steeg was committed to benevolent civilian administrations in the colonies. However, Steeg inherited a system in Algeria where the local settler assemblies dominated by wealthy landowners controlled taxation and spending.[10] There was a tendency to favor spending that boosted to economy over spending on social projects. When Steeg resubmitted the 1914 plan for an asylum at Blida, the assembly delayed approval of funding.[19] Steeg was able to initiate major irrigation projects to improve agricultural productivity, a policy he would later repeat in Morocco.[20] He became known as the "water governor".[21]

Steeg supported cooperation between Algerian and French West African (AOF) forces in combating rezzous (Tuareg raids) in the western Sahara, a constant source of insecurity that prevented development of north-south transport routes.[22] In February 1923 he met in Algiers with his counterparts Marshal Hubert Lyautey of Morocco and Lucien Saint of Tunisia to discuss common problems. They agreed that the western Sahara must be treated as a whole, ignoring arbitrary boundaries.[23] Nomadic migration across borders would be allowed but smuggling would not. A joint Algerian-Moroccan police force would operate from a base at Forthassa Rharbia.[24]

On 17 April 1925 Steeg was unexpectedly called back to France to become Minister of Justice in Painlevé's second cabinet.[3] Painlevé needed left-wing politicians such as Steeg, Briand, Caillaux, Monzie and Laval in his cabinet so he could gain support for his program, which was essentially conservative.[25] Steeg was succeeded in Algeria by Viollette.

Morocco (1925–1928)

In April 1925 Abd-el-Krim proclaimed the independent Rif Republic in the Rif region of Spanish Morocco.[26] He advanced south into French Morocco, defeating French forces and threatening the capital, Fes.[27] The resident-general, Hubert Lyautey, was replaced as military commander by Philippe Pétain on 3 September 1925.[28] On 11 October 1925 Steeg replaced Lyautey as resident-general with the mandate of restoring peace and making the transition from military to civilian government.[3] Lyautey received very little recognition for his achievement in securing Morocco as a colony.[29] Steeg would have been willing to give autonomy to the people of the Rif, but was overruled by the army.[30] Abd-el-Krim surrendered to Pétain on 26 May 1926 and was deported to Réunion in the Indian Ocean, where he was held until 1947.[31] Steeg said he wanted Abd el Krim to be "neither exalted nor humiliated, but in time forgotten."[32]

Steeg moved quickly to resolve the most acute social problems.[33] Steeg appointed men who had worked with him in Algeria to key posts, and brought many more Frenchmen into the administration.[34] There were 66,000 Europeans in Morocco when he arrived, most of them citizens of France.[35] Steeg favored bringing more French settlers into the country.[36] In his first three years he introduced almost as many colonists to Morocco as his predecessor had in thirteen.[37] Steeg issued a decree of 4 January 1927 that created a fund for large scale irrigation projects such as the El Kansera dam on the Beth and the N'fis dam, both of which were started that year.[38] Through his "grands barrages" projects he planned to bring year-round irrigation to 250,000 hectares (620,000 acres) of land.[39] Irrigation would make new land available for French settlers, and would allow for denser settlement.[40]

Steeg temporarily banned the Ha-Olam journal of the World Zionist Organization, but generally allowed publication of pro-Zionist newspapers and permitted Zionist activity.[41] At a meeting of the French League for Human Rights in 1926 he said that the Jews were progressing faster than Muslims. Educated Moroccan Jews should be able to apply to become French citizens.[42]

Some observers were disturbed by the shift from Lyautey's sympathy for the Moroccans and respect for their customs to Steeg's policy of land expropriation and French colonization, which seemed sure to create mounting hostility between the two peoples.[43] Steeg favored assimilation of the indigenous cadres into the French administration to avoid competition between the two, which he felt would weaken the government's authority.[44] In contrast to Lyautry, Steeg spent little time with the Sultan and other members of the Moroccan elite.[34] His selection of Sidi Mohammed Ben Youssef as the new Sultan in 1927 may have been due to a desire for an inexperienced young ruler who would conform to his wishes.[45]

The effect of Steeg's policies was for the traditional elite to lose power as pastoralists and subsistence farmers left the land to work for wages in the city.[46] Many of the new colons came from Algeria, and were intolerant to the "natives", seeing them as no more than unskilled laborers. Racial tensions increased.[35] There was growing demand for Moroccan labor, and labor shortages emerging in some areas.[33] Steeg was pressed by socialists to pass social laws to give workers the same protection as in France, and to create organizations for the protection of labor. He responded that because of the many foreign workers, and an indigenous population not yet ready to benefit from such measures, he could do no more than study the possibility.[47] Various "seditious" organizations emerged with communist or pan-Islamic goals, or both, including the Egypt-based Union Maghrébine and El Mountadda el Abaddi. In a report to the Foreign Ministry of 27 December 1927, Steeg said the Union Maghrébine had 1,500 supporters in the cities of Fez, Casablanca and Tangiers. The Sûreté kept these groups under observation, routinely arresting and imprisoning leaders and seizing material.[48]

A fourth North African conference was held in Algiers in May 1927. Steeg participated for Morocco, Maurice Viollette for Algeria and Lucien Saint for Tunisa. General Jules Carde of French West Africa was represented by Albert Duchêne, the Director of Political Affairs at the Ministry of Colonies.[49] Steeg was asked to act more decisively to suppress dissidence in the region to the south of the Atlas Mountains. However, Moroccan forces were still tied up in what was proving to be a slow campaign to eliminate resistance in the north of the High Atlas.[50] It was agreed that troops from Algeria and Mauritania could enter Moroccan territory, up to defined boundaries, but without prejudice to Morocco's later taking part in pacifying the western Sahara.[51]

In 1927 Steeg was re-elected to the Senate. When the Pujols, Gironde, cantonal elections of 1928 were held, Steeg was unable to retain his position as General Counsel of Gironde while also sitting as Senator for the Seine and holding office in Morocco.[52] Steeg left the Residence of Morocco in January 1929 and was replaced by Lucien Saint.[53]

Later career (1929–1950)

From 1929 to 1935 Steeg was a member of the Committee on Colonies, and became president of the committee. He also belonged to the Foreign Affairs Committee, the Committee of Algeria and the Education committee. Steeg was Minister of Justice in Camille Chautemps's short-lived government (21 February – 1 March 1930) replacing Lucien Hubert. He was succeeded in this position by Raoul Péret.[3]

The government of André Tardieu was defeated by a Senate vote at the start of December 1930, and after several days of negotiation a new government was formed, headed by Steeg, much further to the left than any recent governments.[54] He accepted the position of President of the Council, and simultaneously Minister of Colonies, on 13 December 1930.[3] The right-wing Action Française launched violent attacks on the new government. It called the Minister of Defense, Louis Barthou, "mad, vicious, corrupt". Steeg, the son and grandson of Prussians, was clearly a traitor.[54] Although he had the support of the Senate, he could not get a stable majority in the House for his moderate policies, and was thrown out of office on 22 January 1931 when he lost a vote on agricultural policy and wheat speculation.[3]

Steeg was elected to the Senate again on 14 January 1936. He remained chairman of the committee on the Colonies and member of the committees on Foreign Affairs, Algeria and Education.[3] Under the first government of Léon Blum (in office 4 June 1936 – 22 June 1937) Steeg was appointed head of a commission to study socio-economic conditions in the French colonial empire.[55] The North African sub-committee included leading figures such as Paul Reynaud, Henry Bérenger, Charles-André Julien and Paul Rivet. Meeting on 8 July 1937, this sub-committee decided to focus on labor conditions in the Maghreb.[lower-alpha 2][56] They were too late to prevent the escalation of widespread and violent labor unrest in the region, which was violently suppressed.[57]

Steeg was briefly Minister of Colonies in Camille Chautemps's fifth cabinet, from 18 January to 13 March 1938.[3] He replaced Marius Moutet, a supporter of a plan to settle Jewish refugees in Madagascar.[58] Steeg was hostile to this plan. He said that the urbanized Jewish settlers would not have the skills needed to work the land, but would engage in small-scale commerce "at the expense of the local economy and the natives."[59] He also said the plan would be too expensive, and would be widely criticized in the press. Steeg recommended that Jews should look for help to the Jewish Colonization Association rather than to his ministry.[60]

Steeg was Minister of State in Léon Blum's second cabinet (13 March 1938 – 10 April 1938). World War II broke out in September 1939. After the armistice with Germany, at the Congress of Vichy on 10 July 1940 Steeg voluntarily abstained during the vote on transferring constitutional powers to Marshal Philippe Pétain. Théodore Steeg died on 19 December 1950 in the 14th arrondissement of Paris at the age of 82.[3]

Summary of Cabinet positions

| Ministry | Premier | Start | End |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Instruction and Beaux-Arts | Ernest Monis | 2 March 1911 | 14 January 1912 |

| Interior | Raymond Poincaré | 14 January 1912 | 21 January 1913 |

| Public Instruction and Beaux-Arts | Aristide Briand | 21 January 1913 | 21 March 1913 |

| Public Instruction and Beaux-Arts | Alexandre Ribot | 20 March 1917 | 1 September 1917 |

| Interior | Paul Painlevé | 1 September 1917 | 16 November 1917 |

| Interior | Alexandre Millerand | 20 January 1920 | 24 September 1920 |

| Interior | Georges Leygues | 24 September 1920 | 16 January 1921 |

| Justice | Paul Painlevé | 17 April 1925 | 10 October 1925 |

| Justice | Camille Chautemps | 21 February 1930 | 1 March 1930 |

| Colonies | (self) | 13 December 1930 | 27 January 1931 |

| Colonies | Camille Chautemps | 18 January 1938 | 13 March 1938 |

| Minister of State | Léon Blum | 13 March 1938 | 10 April 1938 |

Steeg's Cabinet, 13 December 1930 – 27 January 1931

- Théodore Steeg – President of the Council and Minister of Colonies

- Aristide Briand – Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Louis Barthou – Minister of Defense

- Georges Leygues – Minister of the Interior

- Louis Germain-Martin – Minister of Finance

- Louis Loucheur – Minister of National Economy, Commerce, and Industry

- Maurice Palmade – Minister of Budget

- Édouard Grinda – Minister of Labour and Social Security Provisions

- Henri Chéron – Minister of Justice

- Albert Sarraut – Minister of Military Marine

- Charles Daniélou – Minister of Merchant Marine

- Paul Painlevé – Minister of Air

- Camille Chautemps – Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts

- Robert Thoumyre – Minister of Pensions

- Victor Boret – Minister of Agriculture

- Édouard Daladier – Minister of Public Works

- Henri Queuille – Minister of Public Health

- Georges Bonnet – Minister of Posts, Telegraphs, and Telephones

Changes

- 23 December 1930 – Maurice Dormann succeeds Thoumyre as Minister of Pensions.

Bibliography

- Steeg, Théodore (1903). Edgar Quinet (1803–1875). L'oeuvre, le citoyen, l'éducateur. E. Cornély. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- Steeg, Théodore (1905). Union démocratique de la Somme. Conférence faite à l'Alcazar, le 16 avril 1905, par T. Steeg,... impr. du "Progrès de la Somme. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- Steeg, Jules Joseph Théodore (1912). La réforme électorale et l'union des républicains: discours prononcé le 25 octobre 1912. Éditions de la Ligue d'Union Républicaine pour la Réforme Électorale. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- Steeg, Jules Joseph Théodore (1917). L'Effort Charitable de la Suisse. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- Steeg, Théodore (1922). Les territoires du sud de l'Algérie: éxopsé de leur situation. Ancienne maison Bastide-Jourdan. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- Steeg, Théodore (1923). Exposé de la situation générale de l'Algérie en 1922.

- Steeg, Jules Joseph Théodore (1926). La Paix Française en Afrique Du Nord, Etc. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- Chauvelot, Robert; Steeg, Théodore (1931). Où va l'Islam ? Stamboul, Damas, Jérusalem, Le Caire, Fez, le Sahara... [2e édition.]. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- Thézard, Joël; Steeg, Théodore (1935). Arabesques. Préface de T. Steeg,... Éditions Artes-Tuae (Thézard). Retrieved 2013-07-05.

References

- ↑ Jules Steeg (1836–1898), was a pastor of the reformed church at Gensac, Gironde and then at Lilbourne from 1865 to 1877. Jules Steeg was founder and editor in chief of the liberal journal Progrès des communes in Bordeaux (1869), editor in chief of Patriote in Libourne, and then of L'Union républicaine in Bordeaux. Jules Steeg was a radical deputy for Bordeaux, Gironde, from 1881 to 1889, and was one of the founders of the Republican party. In 1890 Jules Steeg was appointed inspector-general of public education in charge of the pedagogic museum. From 1896 to 1898 he was director of the École Normale Primaire Superieure of Fontenay-aux-Roses. [1]

- ↑ The Maghreb is the region of North Africa that includes Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schweitz 2001, p. 548.

- ↑ Weber 1962, p. 129.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Jolly 1977.

- ↑ Robin 2007, p. 137.

- ↑ Delaunay 2010, p. 683.

- ↑ Robin 2007, p. 268.

- ↑ Scotti 2010, p. 32.

- ↑ Shurts 2007, p. 149.

- ↑ Keller 2008, p. 49.

- 1 2 Keller 2008, p. 50.

- ↑ Maier 1975, p. 108.

- ↑ Maier 1975, p. 109.

- ↑ Wohl 1966, p. 164.

- ↑ Wohl 1966, p. 165.

- ↑ Maier 1975, p. 235.

- ↑ Hardman 2009, p. 120.

- ↑ Haddour 2000, p. 7.

- ↑ Hardman 2009, p. 121.

- ↑ Keller 2008, p. 51.

- ↑ Swearingen 1988, p. 33.

- ↑ Perennes 1993, p. 126.

- ↑ Trout 1969, p. 233.

- ↑ Trout 1969, p. 254.

- ↑ Trout 1969, p. 255.

- ↑ Weber 1962, p. 159.

- ↑ Lepage 2008, p. 125.

- ↑ Lepage 2008, p. 126.

- ↑ Griffiths 2011, p. 111.

- ↑ Woolman 1968, p. 195.

- ↑ Griffiths 2011, p. 113.

- ↑ Ansprenger 1989, p. 88-89.

- ↑ Woolman 1968, p. 208.

- 1 2 Ayache 1990, p. 31.

- 1 2 Trout 1969, p. 260.

- 1 2 Slavin 2001, p. 86.

- ↑ Perennes 1993, p. 131.

- ↑ Swearingen 1988, p. 51.

- ↑ Swearingen 1988, p. 53.

- ↑ Swearingen 1988, p. 54.

- ↑ Swearingen 1988, p. 52.

- ↑ Lasḳier 1983, p. 210.

- ↑ Lasḳier 1983, p. 167.

- ↑ Singer & Langdon 2008, p. 224.

- ↑ Ayache 1990, p. 55.

- ↑ Trout 1969, p. 261.

- ↑ Slavin 2001, p. 85.

- ↑ Ayache 1990, p. 58.

- ↑ Thomas 2008, p. 102-103.

- ↑ Trout 1969, p. 266.

- ↑ Trout 1969, p. 267.

- ↑ Trout 1969, p. 268.

- ↑ Robin 2007, p. 198.

- ↑ Ayache 1990, p. 61.

- 1 2 Weber 1962, p. 297.

- ↑ Thomas 2012, p. 129.

- ↑ Thomas 2012, p. 130.

- ↑ Thomas 2012, p. 131.

- ↑ Watt 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ Caron 1999, p. 155-156.

- ↑ Caron 1999, p. 156.

Sources

- Ansprenger, Franz (1989-01-01). The Dissolution of the Colonial Empires. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-03143-1. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Ayache, Albert (1990). Le mouvement syndical au Maroc: La Marocanisation 1943–1948 (in French). L'Harmattan. p. 31. ISBN 978-2-85802-231-1. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Caron, Vicki (1999). Uneasy Asylum: France and the Jewish Refugee Crisis, 1933–1942. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4377-8. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Delaunay, Jean-Marc (2010). Méfiance cordiale – Les relations franco-espagnoles de la fin du XIXe siècle à l: Volume 2 : Les relations coloniales (in French). L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-54484-0. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- Griffiths, Richard (2011-05-19). Marshal Pétain. Faber & Faber. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-571-27909-8. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Hardman, Ben (2009). Islam and the Métropole: A Case Study of Religion and Rhetoric in Algeria. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-0271-4. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Jolly, Jean (1977). "STEEG (JULES, JOSEPH, Théodore)". Dictionnaire des parlementaires français: notices biographiques sur les ministres, sénateurs et députés français de 1889 à 1940 (in French). Presses universitaires de France. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- Haddour, Azzedine (January 2000). Colonial Myths: History and Narrative. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-5992-6. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Keller, Richard C. (2008-09-15). Colonial Madness: Psychiatry in French North Africa. University of Chicago Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-226-42977-9. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Lasḳier, Mikhael M. (1983). The Alliance Israélite Universelle and the Jewish Communities of Morocco: 1862–1962. SUNY Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-4384-1016-6. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Lepage, Jean-Denis G.G. (January 2008). The French Foreign Legion: An Illustrated History. McFarland. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-7864-6253-7. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Maier, Charles S. (1975). Recasting Bourgeois Europe: Stabilization in France, Germany and Italy in the Decade After World War I. Princeton University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-691-10025-8. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Perennes, Jean Jacques (1993). L'Eau et les hommes au Maghreb: contribution à une politique de l'eau en Méditerranée (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 978-2-86537-357-4. Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- Robin, Christophe-Luc (2007-05-01). Les hommes politiques du Libournais de Decazes à Luquot: Parlementaires, conseillers généraux et d'arrondissement, maires de l'arrondissement de Libourne de 1800 à 1940 (in French). Editions L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-17128-2. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Schweitz, Arlette (2001). "Steeg, Jules Joseph Théodore". Les Parlementaires de la Seine sous la Troisième République: Etudes (in French). Publications de la Sorbonne. ISBN 978-2-85944-432-7. Retrieved 2013-07-06.

- Scotti, R. A. (April 2010). Vanished Smile: The Mysterious Theft of the Mona Lisa. VINTAGE BOOKS. ISBN 978-0-307-27838-8. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Shurts, Sarah E. (2007). Redefining the "engagé": Intellectual Identity and the French Extreme Right, 1898–1968. ProQuest. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-549-12865-6. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Singer, Barnett; Langdon, John W. (2008-02-01). Cultured Force: Makers and Defenders of the French Colonial Empire. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-299-19904-3. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Slavin, David Henry (2001-10-09). Colonial Cinema and Imperial France, 1919–1939: White Blind Spots, Male Fantasies, Settler Myths. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6616-6. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Swearingen, Will D. (1988). Moroccan Mirages: Agrarian Dreams and Deceptions, 1912–1986. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-071-1. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Thomas, Martin (2008). Empires of Intelligence: Security Services and Colonial Disorder After 1914. University of California Press. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0-520-93374-3. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Thomas, Martin (2012-09-20). Violence and Colonial Order: Police, Workers and Protest in the European Colonial Empires, 1918–1940. Cambridge University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-521-76841-2. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Trout, Frank E. (1969). Morocco's Saharan Frontiers. Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-04495-0. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Watt, Sophie Laurence (2008). Constructions of Minority Identity in Late Third Republic France. ProQuest. ISBN 978-1-109-02400-5. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Weber, Eugen (1962). Action Française: Royalism and Reaction in Twentieth Century France. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0134-1. Retrieved 2013-07-07.

- Wohl, Robert (1966-01-01). French Communism in the Making, 1914–1924. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0177-8. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Woolman, David S. (1968). Rebels in the Rif: Abd El Krim and the Rif Rebellion. Stanford University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-8047-0664-3. Retrieved 2013-07-07.