Roll, Jordan, Roll

"Roll, Jordan, Roll" (Roud 6697), also "Roll, Jordan", is a spiritual written by Charles Wesley in the 18th century which became well-known among slaves in the United States during the 19th century. Appropriated as a coded message for escape, by the end of the American Civil War it had become known through much of the eastern United States. In the 20th century it helped inspire blues, and it remains a staple in gospel music.

History

The tune known as "Roll, Jordan, Roll" was written by the English Methodist preacher Charles Wesley in the 18th century. It was introduced to the United States by the early 19th century, in states such as Kentucky and Virginia, as part of the Second Great Awakening, and often sung at camp meetings. From there, it was introduced to Black slaves by a planter or missionary, in an attempt to Christianize the slaves and eliminate their faith in traditional religions; this was hoped to make the slaves more docile, and thus easier to control.[1]

The song soon became popular with the slaves. According to Ann Powers of NPR, it became a "primary example of slaves' claiming and subverting a Christian message to express their own needs and send their own messages". The River Jordan of the song became a coded message for escape, calling to mind the Mississippi or Ohio Rivers, both of which led to the slave-free northern United States and thus freedom.[2]

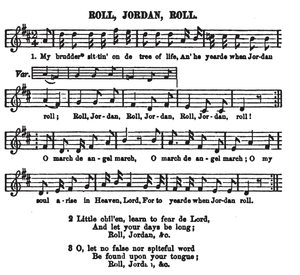

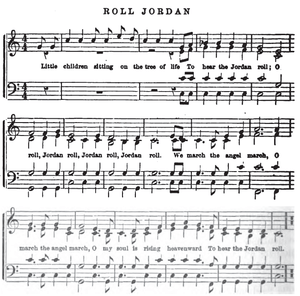

The American war journalist Charles Carleton Coffin, who heard a performance of the song in Blythewood, South Carolina, in 1863, described "Roll, Jordan, Roll" as already having become a favourite song, with many versions to be found.[3] A year later, a version was published in Slave Songs of the United States (compiled by abolitionists William Francis Allen, Lucy McKim Garrison, and Charles Pickard Ware).[4] The editors, who positioned the song "in a place of honor" as the first entry in the book,[2] noted that the song could be found from South Carolina down to Florida, and described it as "one of the best known and noblest" of Black spirituals.[4] By 1920 over fifty publications had reproduced or referenced the song.[5]

"Roll, Jordan, Roll" influenced a variety of songs. The refrain of Stephen Foster's "Camptown Races", for instance, is considerably similar to the spiritual, and the melodies likewise have parallels.[6] By the early 20th century, Stephen Calt writes, "Roll, Jordan, Roll" had influenced the creation of a new genre, blues, though likely through an undocumented secular version of the song. He finds compositional similarities in "Roll, Jordan, Roll" and all blues songs.[7] Early blues songs, such as "Bad-luck Blues" (1927) and "Cool Drink of Water" (1928), used a similar structure to that of "Roll, Jordan, Roll".[7] "Roll, Jordan, Roll", meanwhile, became a standard of the Fisk Jubilee Singers and has remained a staple of gospel music.[2]

The song was adapted, together with several other Black spirituals, by Nicholas Britell for the 2013 film 12 Years a Slave, Steve McQueen's adaptation of the memoir by Solomon Northup. Britell, in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter, stated that he felt compelled to rearrange the song because "it was very important to create a world that was very unique", and the original lyrics were already well known.[8] Powers found that the film's use of "Roll, Jordan, Roll" served as a counterpoint to "Run, Nigger, Run", a song of warning appropriated by the White overseer John Tibeats (portrayed by Paul Dano): where "Run, Nigger, Run" is used as a "taunt" to break the slaves' spirits, "Roll, Jordan, Roll" serves to reaffirm the character Northup's desire to not just survive, but live.[2]

Composition, contents, and performance

"Roll, Jordan, Roll" is constructed as four-bar phrases, with a ten-beat line followed by a six-beat refrain.[7] The first two phrases close with a keynote, and the lyrics are presented with an AABB rhyme scheme.[9] This construction, according to Calt, was reflected in the construction of blues songs in the early 20th century.[7]

The Jordan of the song's lyrics is a reference to the River Jordan, which in Biblical tradition the Israelites crossed to enter the Promised Land. As such, by crossing the Jordan River, the singers are expected to be able to set down their burdens and live life without trouble.[10] Owing to this symbolism, songs related to the River Jordan were not uncommon; Newman Ivey White, writing in 1928, noted that several writers had commented on slaves' fondness for including the river in their spirituals.[11]

Coffin recorded performances of the song as substituting the names of audience members or participants as sitting on the Tree of Life, for instance a Mr. Jones, with each progressive rendition of the song substituting a different individual.[12] Elizabeth Kilham, who listened to the song in a church, noticed a similar trend. However, rather than name members of the congregation, the version sung by the church went through a number of Biblical figures, including Jesus, the archangel Gabriel, and the prophet Moses. This was followed by friends and relatives, including "my fader" and "my mudder", before ultimately culminating with a number of people respected by the congregation, including former president Abraham Lincoln and Union general Oliver O. Howard.[13] As the performance continued, it became more enthusiastic.[12] Coffin describes the performance:

They [the performers] beat time, at first, with their hands, then their feet. ... They go round in a circle, shuffling, jerking, shouting louder and louder, while those outside of the circle responds with increasing vigor, all stamping, clapping their hands, and rolling out the chorus. William [a performer] seems to be in a trance, his eyes are fixed, yet he goes on with a double-shuffle, till the perspiration stands in beads upon his face. Every joint seems hung on wires. Feet, legs, arms, head, body, and hands swing and jump like a child's dancing Dandy Jim. ... Thus it went on till nature was exhausted.[14]

References

- ↑ Calt 2008, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 Powers 2013, '12 Years a Slave'.

- ↑ Coffin 1866, p. 230.

- 1 2 Allen, Garrison & Ware 1867, p. 1.

- ↑ Southern & Wright 1990, whole.

- ↑ Pruett 2007, p. 92.

- 1 2 3 4 Calt 2008, p. 35.

- ↑ Girkout 2013, '12 Years a Slave'.

- ↑ Calt 2008, p. 40.

- ↑ Chase 1992, p. 198.

- ↑ White 1928, p. 87.

- 1 2 Coffin 1866, pp. 230–231.

- ↑ Kilham 1870, p. 307.

- ↑ Coffin 1866, p. 231.

Works cited

- Allen, William Francis; Garrison, Lucy McKim; Ware, Charles Pickard, eds. (1867). Slave Songs of the United States. New York: Peter Smith. OCLC 220782519.

- Calt, Stephen (2008). I'd Rather Be the Devil: Skip James and the Blues. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-56976-996-6.

- Chase, Gilbert (1992). America's Music: From the Pilgrims to the Present. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06275-9.

- Coffin, Charles Carleton (1866). Four Years of Fighting: A Volume of Personal Observation with the Army and Navy, from the First Battle of Bull Run to the Fall of Richmond. Boston: Ticknor and Fields. OCLC 3351438.

- Girkout, Alexa (9 December 2013). "'12 Years a Slave' Composer Reveals the Challenges of Re-Creating Authentic Slave Songs". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- Kilham, Elizabeth (1870). "Sketches in Color". Putnam's Magazine: 31–38, 205–10, 304–11.

- Powers, Ann (13 November 2013). "'12 Years A Slave' Is This Year's Best Film About Music". NPR. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- Pruett, Laura Moore (2007). Louis Moreau Gottschalk, John Sullivan Dwight, and the Development of Musical Culture in the United States, 1853-1865 (Thesis). Florida State University. OCLC 234444031.

- Southern, Eileen; Wright, Josephine, eds. (1990). African-American Traditions in Song, Sermon, Tale, and Dance, 1600s–1920: An Annotated Bibliography of Literature, Collections, and Artworks. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-24918-1.

- White, Newman Ivey (1928). American Negro Folk-Songs. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC 411447.