Rauðúlfs þáttr

Rauðúlfs þáttr is a short allegorical story preserved in Iceland in a number of medieval manuscripts. The author is unknown but was apparently a 12th–13th century ecclesiastical person. The story is about Saint Olav’s (Olav Haraldsson II king of Norway 995–1030) visit to a wise man named Rauðúlfr (also called Rauðr and Úlfr), their entertainment in the evening, the staying overnight in a round, rotating and richly decorated house and a vision the king had in his dream that night. The story is sometimes incorporated in the Separate Saga of St. Olaf.[1]

The visit

The story relates King Olav’s trip with his retinue, including the queen and bishop, to “Eystridalir” (now Österdalen) a then rather remote part of Norway, bordering on Sweden. He visits Rauðúlfr and his family who have been accused of cattle theft. Rauðúlfr and his two sons, Dagr and Sigurðr, turn out to be wise men, skilled in astronomy, time reckoning and physiognomy among other things. There is a feast in the evening where the king asks the bishop and six noblemen together with their host to relate about their skills, which they do one by one. After that the king and his retinue are led to a new house in the yard to spend the night.

The rotating house

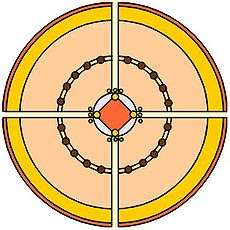

The geometry and ornaments of the house are described in detail. The house was round, with four doors placed equidistantly. The roof had a dome, supported by twenty pillars. The house was divided into four quarters (presumably by corridors leading from the doors to the centre). The house was also divided in three concentric parts: a round central platform with steps and two outer parts divided by a fence. The central platform had a large bed where king Olav was to sleep. The bedposts had large spheres of gilded copper and projecting iron bars, each supporting a tripartite candle. The king’s retinue was ordered by rank as follows. The queen was in the quarter on his left side with her ladies in waiting. The bishop was in the quarter on his right with the clerics. Three noblemen were in the quarter above the king’s head, but three others in the opposite quarter. Twenty people slept in each quarter in the inner ring, but forty in the outer ring, 200 people altogether.

As the king lay in the bed he observed that the ceiling was all decorated with scenes depicting the entire creation. The apex of the dome had the godhead in a mandorla surrounded by the orders of angels. Out from there were the planets then the clouds and winds, then terrestrial plants and animals and finally the sea and sea creatures. The outer ceiling, outside the pillars, had stories depicted of ancient deeds. Just before the king fell asleep he noticed that the house was rotating.

The dream

King Olav then had a most peculiar dream. When he woke up the next morning he went to see Rauðúlfr and asked him to decipher it. Rauðúlfr knew the dream without being told, described it to Olav (and the reader) and expounded its meaning. King Olav had seen a huge crucifix, a green cross with a human figure. This figure was made of metals and other materials with a more or less decreasing value from head to feet. The head was made of red gold (Icelandic: rautt gull) which glowed like ‘lýsigull’ (bright gold[2]) and had a long and golden hair, the neck was of copper, surrounded by Greek fire, the breast and arms were of pure silver engraved with the paths and figures of the heavenly bodies. The uppermost part of the belly was made of polished iron decorated with the deeds of some ancient heroes like Sigurðr Fáfnisbani, Haraldur hilditönn and Harald fairhair. The middle part of the abdomen was made of impure gold and was decorated with trees, herbs and terrestrial animals. The lowest part of the belly was made of undecorated impure silver. The thighs had skin or flesh colour and the legs below the knees were made of wood. Rauðúlfr interpreted the dream vision as the successive reigns of kings of Norway down from the reign of Olav, who represented the golden head and the glory of Heaven, to about 1155 when the reign had been divided (the legs). By a series of ingenious puns Rauðúlfr linked the character of each of King Olav’s successors (or their reign) with the material or decoration of the corresponding part of the crucifix. Rauðúlfr further explained that the house was rotating in harmony with the sun. Before the king departed Rauðúlfr demonstrated the use of a (legendary) sunstone to locate the sun in an overcast sky. Finally, Rauðúlfr and his family were proven innocent of the cattle thefts. On the king’s departure Rauðúlfr’s two sons joined his retinue.

Research

Early researchers noted the debt Rauðúlfs þáttr owed to the dream of Nebuchadnezzar in the Old Testament. His dream was of a huge image made of various materials (gold, copper, iron, etc.). The prophet Daniel interpreted it to stand for the rise and fall of world powers (Chapter 2). The likeness of events at the feast with a similar but much exaggerated narration in the French chanson de geste Voyage de Charlemagne à Jérusalem et à Constantinople[3] was also noted.[4][5] Both stories also feature a round and rotating house. The round house in the French song has been compared with “abodes of the Sun” in Greek medieval romances.[6][7] Later studies indicate that Rauðúlfs þáttr is an allegory that uses a host of symbolic imagery of cosmological nature to manifest the holiness of King Olav (=Saint Olav).[8][9] The round house can be seen as a prefiguration of the Church[10] and an image or model of the universe. The crucifix is a reflection of the house in the same way as man was seen as a microcosmos, or mirror image, of the universe.[11][12] The central platform corresponds to the head, the decorations of the ceiling correspond to the body parts further away from the head. The author places King Olav in the central position of the house, in a bed surrounded by symbols of the New Jerusalem (4x3 lights), the symbolic seat of Christ.[13] The effect is a glorification or apotheosis of King Olav. As an image of the universe the house can also be envisaged as a symbolic man composed of a four-divided, earthly body and a heavenly, central and undivided soul (the central platform). As such this allegorical house might well have served as a tool for meditation. The symbolic imagery of Rauðúlfs þáttr is close to that used in the cosmological visions of Hildegard of Bingen,[14] both works represent a widespread tradition of cosmological imagery within the medieval church. Other examples of such imagery appear in church architecture, medieval architectural allegories in the literature,[15][16] the cave of love in Tristan and Isolde by Gottfried von Strassburg,[17] and as a cosmogram in Byrhtferth’s Enchiridion.[18]

The crucifix and the kings of Norway, a table

| Part of body | Material | Decoration | Reign |

|---|---|---|---|

| Head | Luminous red gold (rautt gull) | Rainbow coloured mandorla. Angels and heavenly glory | Ólafur Haraldsson (St. Olav) (1015–1028) |

| Neck | Copper | Greek fire (skoteldur) | Sveinn Alfífuson (1030–1035) |

| Breast and arms | Refined silver (brennt silfur) | Paths of the heavenly bodies (sun moon and stars/planets) | Magnús góði Ólafsson (1035–1047) |

| Below breast | Polished iron | Sagas of ancient kings and heroes | Haraldur harðráði (1047–1066) |

| Belly above navel | Gold alloy (electrum) (bleikt gull) | Trees, flowers and tetrapods | Ólafur kyrri (1066–1093) |

| Belly: navel to genitals | Silver alloy (unrefined silver)(óskírt silfur) | Magnús berfættur (1093–1103) | |

| Thighs | Flesh coloured material | Sigurður Jórsalafari (d. 1130) and Eysteinn Magnússon (d. 1123) | |

| Legs and feet | Wood | A time of strife between the (claimed) sons and grandsons of Magnús berfættur |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Johnsen, O.A. and Jón Helgason (eds.) 1941. Saga Óláfs konungs hins helga. Den store saga om Olav den hellige. Efter pergamenthandskrift i Kungliga Biblioteket i Stockholm nr. 2 4to med varianter fra andre handskrifter. Norsk Historisk Kjeldeskrifts-Institutt. Oslo. Vol. II.

- ↑ Cleasby-Vigfússon (1874), Lyritareiðr-Lýsing

- ↑ Picherit, J.-L. G. (ed. and transl.) 1984. The Journey of Charlemagne to Jerusalem and Constantinople. Summa Publications, Inc. Birmingham, Alabama.

- ↑ Turville-Petre, Joan E. 1947. The story of Rauð and his sons. Transl. from the Icelandic by J.E. Turville-Petre. Viking Society for Northern Research. Payne Memorial Series II.

- ↑ Faulkes, Anthony. 1966. Rauðúlfs þáttr. A study. Studia Islandica 25. Heimspekideild Háskóla Íslands og Bókaútgáfa Menningarsjóðs. Reykjavík.

- ↑ Schlauch, M. 1932. The palace of Hugon of Constantinopel. Speculum 7: 500-514.

- ↑ Faulkes, Anthony. 1966. Rauðúlfs þáttr. A study. Studia Islandica 25. Heimspekideild Háskóla Íslands og Bókaútgáfa Menningarsjóðs. Reykjavík.

- ↑ Einarsson, Árni. 1997. Saint Olaf’s dream house. A medieval cosmological allegory. Skáldskaparmál 4: 179–209, Stafaholt, Reykjavík.

- ↑ Einarsson, Árni. 2001. The symbolic imagery of Hildegard of Bingen as a key to the allegorical Raudulfs thattr in Iceland. Erudiri Sapientia II: 377–400.

- ↑ Loescher, G. 1981. Rauðúlfs þáttr. Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und Deutsche Literatur 110: 253–266.

- ↑ Kurdzialek, M. 1971. Der Mensch als Abbild des Kosmos. Miscell. Med. 8: 35-75.

- ↑ Einarsson, Árni. 1997. Saint Olaf’s dream house. A medieval cosmological allegory. Skáldskaparmál 4: 179–209, Stafaholt, Reykjavík.

- ↑ Meyer, Ann R. 2003. Medieval Allegory and the Building of the New Jerusalem. D.S. Brewer, Cambridge. 214 pp.

- ↑ Einarsson, Árni. 2001. The symbolic imagery of Hildegard of Bingen as a key to the allegorical Raudulfs thattr in Iceland. Erudiri Sapientia II: 377–400.

- ↑ Mann, J. 1994. Allegorical buildings in medieval literature. Medium Ævum 63: 191-210.

- ↑ Whitehead, Christinia 2003. Castles of the Mind. A Study of Medieval Architectural Allegory. University of Wales Press, Cardiff. 324 pp.

- ↑ Finckh, Ruth 1999. Minor Mundus Homo. Studien zur Mikrokosmos-Idee in der mittelalterlichen Literatur. Palaestra 306. Untersuchungen aus der Deutschen und Skandinavischen Philologie. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. Göttingen. 475 pp.

- ↑ Einarsson, Árni. 1997. Saint Olaf’s dream house. A medieval cosmological allegory. Skáldskaparmál 4: 179–209, Stafaholt, Reykjavík.

Further reading

- Hildegard of Bingen. Book of Divine Works, with Letters and Songs. Edited and introduced by Matthew Fox. Bear & Company, Santa Fe, New Mexico. 1987.

- Hildegard of Bingen. Liber Divinorum Operum. Cura et studio. A. Derolez & P. Dronke (eds.). In: Corpus Christianorum. Continuatio Mediaevalis XCII. Brepols. Turnhout 1996.

- Peck, R. A. 1980. Number as cosmic language. pp. 15–64 in C.D. Eckhardt (ed.): Essays in the Numerical Criticism of Medieval Literature. Associated University Press, London.