Portuguese invasion of the Banda Oriental (1811–12)

| Portuguese invasion of the Banda Oriental | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The countryside of the Banda Oriental (Eastern Bank) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

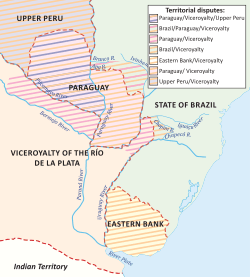

The Portuguese invasion of the Banda Oriental was a short-lived and failed attempt, beginning in 1811 and ending the following year, by the Portuguese Empire to annex the remaining territory of the Spanish Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata.

Background

Coveted Banda Oriental

Portugal had long desired to secure the east bank of the River Plate (Río de la Plata) in South America, which it regarded the natural border of Brazil (the Portuguese Overseas Empire's largest and wealthiest colony).[1] In 1680, the Portuguese founded the Colônia do Santíssimo Sacramento (Colony of the most Saintly Sacrament), the first European settlement on the river's eastern bank.[2][3] It served mainly as a port for smuggling activities between Buenos Aires, which was already one of Hispanic America's major trading centers, and Brazil. Although Sacramento was only a few hours by ship from Spanish Buenos Aires, it was an outpost that was very isolated from Portugal's other possessions, requiring a two weeks sea voyage to reach the colony's capital at Rio de Janeiro. The need for defenses and development to shore up the southern flank was only slowly addressed, however, and the town's population never grew beyond 3,000 under Portuguese rule.[4]

Spain did not lightly dismiss the construction of a settlement on territory it regarded as part of its colonial empire. The Spanish in Buenos Aires protested and demanded the withdrawal of the Portuguese outpost, claiming the entire area as theirs according to the Treaty of Tordesillas, signed centuries before in 1494. The Portuguese refused to comply, citing the same treaty as granting the east bank of the River Plate to them. In fact, the treaty had not assigned the east bank of the river to Portugal; the misconception was a result of a calculation error in determining the location of the demarcation line.[2] Barely a few months after its foundation, Sacramento was captured by the Spanish, but was later returned to the Portuguese early in 1683.[5] In 1704, during the War of the Spanish Succession, the Spanish forces again attacked and overran the Portuguese outpost. It was restored to Portugal only in 1716, after the Treaty of Utrecht was signed.[6]

In 1723, the Portuguese dispatched a small expedition that founded an outpost at Montevideo to the southeast of Sacramento. The new establishment had inadequate support, and was abandoned in 1724. The Spanish took advantage of the vacancy to move in and set up their own outpost in 1726, which became the town of Montevideo.[7][8] To resolve the territorial contention, both nations signed the Treaty of Madrid in 1750, whereby Spain was granted control of Sacramento and Portugal was acknowledged as having jurisdiction over the Seven Missions (the western part of today's Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul).[9][10] Neither side fulfilled its obligations under the treaty, however, and the agreement was subsequently scrapped under the Treaty of El Pardo in 1761.[11][12] Spain finally acquired Sacramento under the Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1777, which gave it control over the entire Banda Oriental (Eastern Bank), as the entire region had come to be known because of its geographical position.[13][14]

Crises in the Hispanic-American colonies

During the French Revolutionary Wars, Spain sided with France and attacked Portugal in 1801, which led to the War of the Oranges. The conflict had mixed results, but the outcome was largely favorable to Portuguese interests. Portugal lost its frontier town of Olivença to Spain, but gained further territories in South America. The Portuguese enlarged the captaincy of Mato Grosso after expelling the Spanish, and they extended their control to the Apa River. The captaincy of Rio Grande do Sul was also expanded with the conquest of the Seven Missions and the seizure of lands extending to the Jaguarão River and to the south beyond, up to the banks of the Chuí. Each side retained the regions it had subjugated, and the status was implicitly acknowledged by the Treaty of Badajoz.[15][16]

The Franco–Hispanic alliance was short-lived. France's Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte betrayed his ally, the Spanish King Don Fernando VII, by arresting and deposing him in favor of Napoleon's own brother Joseph Bonaparte. The Hispanic-American colonies refused to accept the new Spanish king and remained loyal to Fernando VII.[17][18] According to historian Dana Gardner Munro, with "the dethronement of the King, the position of his representatives in America became precarious. The quarrels between different branches of the administration, which had always caused trouble, became more acute when there was no higher authority to whom they could be referred."[19] One of Spain's South American colonies, the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, experienced from the same difficulties. Factions within the viceregal capital, Buenos Aires, contended for power. Viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros was ousted in the May Revolution of 1810 and replaced by a junta (ruling council) formed by members of the native aristocracy who were of Spanish descent.[20][21]

Meanwhile, in Europe, Portugal was faced with imminent invasion by France and Spain, and the Portuguese Royal Family relocated to Rio de Janeiro, capital of Brazil. After their arrival in Rio de Janeiro in early 1808, Prince Regent Dom João (later King Dom João VI) made plans to retaliate. He ordered the invasion of French Guiana, which was conquered in January 1809.[22] He next turned his attention to the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata. The Spanish colony was riven by factional disputes. While the local aristocrats sought to carve out semi-autonomous entities under Fernando VII's suzerainty, some of the more ambitious were looking forward to an eventual and complete break with the Spanish monarchy.[23]

Portugal's territorial ambitions

Sent by Spain to replace Cisneros as viceroy, Francisco Javier de Elío arrived in January 1811. Elio was prevented from landing at Buenos Aires by the ruling junta and sailed instead to nearby Montevideo, the main port of the Banda Oriental.[24][25] Both Buenos Aires and Elío laid claim to be the legitimate government and each attempted to assert control over all the viceroyalty's territories. Buenos Aires sent a military expedition under Manuel Belgrano to the intendancy (roughly province) of Paraguay. The expedition ended in failure, and Belgrano retreated after encountering resistance from troops loyal to Spain.[26][27][28][29] Meanwhile, on 13 February, Elío declared war on Buenos Aires.[30] Orientais (Easterners) led by José Gervasio Artigas rebelled against Elío soon afterward and declared loyalty to the government in Buenos Aires. Belgrano and his men, who had recently returned from Paraguay, joined the Oriental (Easterner) rebellion. He assumed command of all rebel troops, numbering 3,000 men, while Artigas assumed the position of second-in-command.[31]

The rebels subjugated the majority of towns in the Banda Oriental. An increasingly isolated Elío made repeated overtures to the Portuguese.[32] Others within the viceroyalty had already turned to Portugal. The Spanish governor of Paraguay, Bernardo de Velasco y Huidobro, had asked for Portuguese troops, and the same request had been made by the small town of Mandisoví (present-day Federación) in the region of Entre Ríos.[33] Velasco submitted a proposal to Brigadier Dom Diogo de Sousa, captain-general (governor) of Rio Grande do Sul (and later Count of Rio Pardo), for a joint offensive with Portugal (to be joined by Elío) against Buenos Aires.[34] As a token of goodwill, Velasco named Diogo de Sousa governor of the Misiones region, with the day-to-day administration to be in the hands of a representative from Paraguay, Lieutenant Colonel Fulgencio Yegros.[35] The Spanish governor of Paraguay also requested Portuguese troops to occupy the towns of Corrientes and Curuzú Cuatiá in the intendancy of Corrientes.[35]

Despite the pleas for assistance, Portugal never sent any troops and, instead, opted to gather an army under Diogo de Sousa on the border of Banda Oriental. Portugal's Spanish allies were unaware that Diogo de Sousa had already advocated conquest of the Banda Oriental to Prince Regent João, a plan that the latter already had in mind for some time.[36] João hoped to retake Sacramento along with the entire Banda Oriental. Although his goal was feasible, there was little likelihood that the inhabitants of Banda Oriental would welcome Portuguese rule. Although the Portuguese were the first Europeans to discover the River Plate and the first to create a permanent settlement in what would later be known as the Banda Oriental, by this time most development activities had been carried out by the Spanish. The part played by Spain during its formative phases is why present-day Uruguay is regarded as part of Hispanic America, with its Portuguese–Brazilian heritage often downplayed, if not ignored.[37][38]

Portuguese invasion

Occupation of Melo

The Portuguese deployed two army divisions near the border with the Banda Oriental in Rio Grande do Sul. One division, commanded by Field Marshal Manuel Marques de Sousa, camped in the hills of Bagé. It consisted of one infantry battalion from the town of Rio Grande, two squadrons of light cavalry, four cavalry squadrons from the Legion of São Paulo (a militia unit) and one squadron of mounted militiamen (also from the town of Rio Grande).[39][40] The other division was stationed in what became known as the São Diogo camp (at the shore of River Ibirapuitã) and was commanded by Field Marshal Joaquim Xavier Curado (later Count of São João das Duas Barras). The second division comprised two infantry battalions, two horse artillery batteries from the Legion of São Paulo, one regiment of dragoons, one squadron of mounted militiamen from the town of Rio Pardo and one company of Guarani lancers.[39][41] The two divisions were under the command of Diogo de Sousa (who had been promoted to Field Marshal), and together they formed the "Pacifying Army of the Banda Oriental" with a total of 3,000 men. Except for the Portuguese-born Diogo de Sousa, the troops were all natives of Brazil.[42][40][43][44]

In April 1811, Curado's division left the São Diogo camp and joined Marques de Sousa's division.[45] The Portuguese lost one of its main allies on 9 June, after Velasco was ousted and arrested in a coup d'état that eventually resulted in the isolationist dictatorship of José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia.[46] The loss was offset only days later when an expedition sent by Buenos Aires to Upper Peru (to the northwest) retreated after being defeated by forces loyal to Spain.[47][27][28][29] On 17 July, the Pacifying Army was ready to march and began making its way toward Montevideo.[48][49] As the army moved, Diogo de Sousa made an appeal to the Portuguese-speaking inhabitants of Banda Oriental to join him.[upper-alpha 1]

Meanwhile, Spanish Lieutenant Colonel Joaquin de Paz, commanding officer of Melo in Banda Oriental, received orders to expel the village's inhabitants and burn it. Paz was unwilling to obey and sent a letter to Diogo de Sousa requesting troops to garrison the town and prevent the orders for its destruction from being implemented. Marques de Sousa detached two light cavalry squadrons and two dragoon squadrons from the main army and rushed along with them to Melo. They crossed the border on 23 July and reached Melo the same day.[50][51][49] The main body of the Pacifying Army arrived three days later.[50] Diogo de Sousa assigned small units to occupy Spanish outposts along the way.[52] The army marched slowly, hindered by the winter season and lack of supplies. Some soldiers died, and others fell ill, from the intense cold.[51] The army's supply train required 6,000 horses, 1,500 oxen and 140 carts, but it was provided with less than half the necessary number of animals.[upper-alpha 2]

Northwestern invasion

The Portuguese sent another force to the Banda Oriental under Sergeant major (Major) Manuel dos Santos Pedroso. On 7 August Pedroso made a camp at São Xavier on Quaraí River.[53] He crossed the border and on 17 August occupied the town of Belén, located in the northwest of the Banda Oriental.[54] On 25 August Pedroso ordered Captain Joaquim Félix da Fonseca to take nearby Mandisoví on the other shore of the Uruguay River.[55] Pedroso then sent a small force of 60 mounted militiamen under Furriel (Third Sergeant) Bento Manuel Ribeiro to attack the town of Paysandú. On 30 August Bento Manuel defeated 180 or 200 rebels who guarded the town and took control of it.[56][57][58][55] Around 2 September sixteen men who served under the orders of Captain Félix da Fonseca intercepted and defeated a force of 120 Hispanic-American soldiers coming from Curuzú Cuatiá.[59]

Armistice

Marques de Sousa along with 300 cavalrymen headed southeast to the Fortress of Santa Teresa, built by the Portuguese but long in the hands of the Spanish. The stronghold was guarded by 350 rebels and four artillery pieces.[51] When Marques de Sousa and his men arrived on 5 September they discovered that the Oriental garrison had left, but not before they had burned the houses around the fortress, had placed mines and had expelled the civilian population.[60][49] Marques de Sousa divided his men in small groups and sent them after the fleeing rebels. They captured several Orientais and hundreds of horses in the town of Rocha, in Castillos Lagoon and in Castillo Grande.[60][61]

Some time later the Pacifying Army reached Santa Teresa. It departed on 3 October, but before leaving Diogo de Sousa guarded the fortress with 225 or 250 men, equipped with seven cannons, two mortars and one howitzer.[62][49]

Endnotes

- ↑ Diogo de Sousa made the "proclamation" on 21 July (Schröder 1934, p. 126). Portuguese-speaking residents had already been coming to his aid even before his call to arms. On April 9, the Alferes José Machado de Bittencourt enlisted, along with ten men mustered from Mandisoví (Schröder 1934, p. 120). On 1 June, José Lópes Lencina, who had commanded troops under Artigas, joined the Portuguese army (Schröder 1934, p. 123). On 19 June, the priest Mateus Augusto, a farmer who lived near the Chuí Stream, offered his services in the town of Jaguarão (Schröder 1934, p. 124). The Alferes Bento Lópes de Leão also sided with Portugal in the fight on 29 July (Schröder 1934, p. 126). On 15 September, Lieutenant Colonel Pedro José Vieira, who served Artigas, secretly entered in talks to switch sides (Schröder 1934, p. 131).

- ↑ This figure is according to José Feliciano Fernandes Pinheiro (later Viscount of São Leopoldo), who served under Colonel João de Deus Mena Barreto (later Viscount of São Gabriel) during the war (São Leopoldo 1839, p. 292). Historian Celso Schröder gave very different, and far larger, numbers. He said that the army had 10,000 horses and 2,000 oxen (Schröder 1934, p. 126).

References

- ↑ Viana 1994, pp. 255–256.

- 1 2 Viana 1994, p. 256.

- ↑ Bethell 1987, p. 62.

- ↑ Bethell 1987, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Viana 1994, p. 257.

- ↑ Viana 1994, pp. 258–259.

- ↑ Bethell 1987, p. 63.

- ↑ Viana 1994, p. 259.

- ↑ Bethell 1987, pp. 65, 247.

- ↑ Viana 1994, pp. 302–303.

- ↑ Bethell 1987, pp. 247–248.

- ↑ Viana 1994, p. 306.

- ↑ Bethell 1987, p. 248.

- ↑ Viana 1994, pp. 316–317.

- ↑ Bethell 1987, p. 249.

- ↑ Viana 1994, pp. 344–345.

- ↑ Munro 1960, pp. 127–128.

- ↑ Tasso Fragoso 1951, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Munro 1960, p. 127.

- ↑ Munro 1960, pp. 128, 130.

- ↑ São Leopoldo 1839, pp. 289–290.

- ↑ Viana 1994, pp. 380–381.

- ↑ Munro 1960, p. 131.

- ↑ Tasso Fragoso 1951, p. 109.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, pp. 116, 118.

- 1 2 São Leopoldo 1839, p. 290.

- 1 2 Tasso Fragoso 1951, p. 108.

- 1 2 Munro 1960, p. 135.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, p. 117.

- ↑ Tasso Fragoso 1951, p. 110.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, pp. 120–122.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, p. 119.

- 1 2 Schröder 1934, p. 121.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, p. 120.

- ↑ Bethell 1987, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Viana 1994, pp. 254, 256, 259–260.

- 1 2 São Leopoldo 1839, p. 291.

- 1 2 Tasso Fragoso 1951, pp. 114, 116.

- ↑ Tasso Fragoso 1951, pp. 116.

- ↑ São Leopoldo 1839, pp. 291–292.

- ↑ Barroso 1935, pp. 127, 129.

- ↑ Schneider 2009, p. 16.

- ↑ Barroso 1935, p. 129.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, p. 124.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, pp. 124, 128.

- ↑ São Leopoldo 1839, p. 292.

- 1 2 3 4 Silva 1865, p. 120.

- 1 2 Schröder 1934, p. 126.

- 1 2 3 São Leopoldo 1839, p. 293.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, p. 127.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, p. 128.

- 1 2 Schröder 1934, p. 129.

- ↑ Barroso 1935, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Schneider 2009, p. 82.

- ↑ Donato 2001, pp. 401–402.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, p. 130.

- 1 2 São Leopoldo 1839, p. 294.

- ↑ Schröder 1934, pp. 130–131.

- ↑ São Leopoldo 1839, pp. 294–295.

Bibliography

- Barroso, Gustavo (1935). História militar do Brasil (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional.

- Bethell, Leslie (1987). Colonial Brazil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34127-2.

- Donato, Hernâni (2001). Dicionáro das batalhas brasileiras (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: IBRASA. ISBN 85-348-0034-0.

- Munro, Dana Gardner (1960). The Latin American Republics: A History (3 ed.). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Rio Branco, José Maria da Silva Paranhos, Baron of (1999). Efemérides brasileiras (in Portuguese). Brasília: Senado Federal.

- São Leopoldo, José Feliciano Fernandes Pinheiro, Viscount of (1839). Anais da provincial de São Pedro (in Portuguese) (2 ed.). Paris: Tipografia de Casimir.

- Schröder, Celso (1934). "A Campanha do Uruguai em 1811–1812". Revista do Instituto Histórico e Geográfico do Rio Grande do Sul (in Portuguese). Porto Alegre: Barcellos, Bertaso & cia. 14.

- Silva, Domingos de Araujo e (1865). Dicionário histórico e geográfico da província de S. Pedro ou Rio Grande do Sul (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: E. & H. Laemmert.

- Tasso Fragoso, Augusto (1951). A Batalha do Passo do Rosário (in Portuguese) (2 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Freitas Bastos.

- Whigham, Thomas L. (2002). The Paraguayan War: Causes and early conduct. 1. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4786-4.

- Viana, Hélio (1994). História do Brasil: período colonial, monarquia e república (in Portuguese) (15 ed.). São Paulo: Melhoramentos. ISBN 978-85-06-01999-3.

External links

![]() Media related to Portuguese invasion of the Eastern Bank (1811–1812) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Portuguese invasion of the Eastern Bank (1811–1812) at Wikimedia Commons