Eparchy of Marča

| Eparchy of Marča Марчанска епархија[1] | |

|---|---|

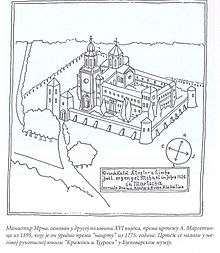

The Marcha Monastery (1775) | |

| Location | |

| Country | Habsburg Monarchy |

| Coordinates | 45°45′48″N 16°29′33″E / 45.76333°N 16.49250°ECoordinates: 45°45′48″N 16°29′33″E / 45.76333°N 16.49250°E |

| Statistics | |

| Members | 60,000–72,000 |

| Information | |

| Rite | Eastern Catholic |

| Established | 21 November 1611 |

| Dissolved | 1753 |

The Eparchy of Marča (Serbian Cyrillic: Марчанска епархија) is term used for designating two historical ecclesiastical entities: Eastern Orthodox eparchy and Eastern Catholic vicariate. The term vas derived from the name of the monastery at Marča (today Stara Marča) near Ivanić-Grad, Habsburg Monarchy (present-day Zagreb County, Republic of Croatia).

Although Serbian Orthodox bishop Simeon Vratanja traveled to Rome in 1611 and formally accepted jurisdiction of the Pope over this bishopric, until 1670 Serb bishops continued to recognize the jurisdiction of the Serb Orthodox Church and Patriarchate of Peć and struggled against conversion attempts by Roman Catholic bishops from Zagreb. This semi-union existed until the 1670 appointment of Pavle Zorčić as bishop. All Serb Orthodox clergy who objected to the union were arrested and sentenced to life in prison in Malta where they died. The bishopric eventually became the Eastern Catholic Eparchy of Križevci.[2]

Name

The name Marča was derived from the name of the nearby hill, Marča. Other names used for this bishopric include Svidnik (Svidnička eparhija), Vretanija (Vretanijska eparhija), and the "Uskok" bishopric.[3]

Background

After the Ottoman capture of Smederevo fortress in 1459 up to 200,000 Orthodox Christians moved into central Slavonia and territory of Srem which today belong to eastern Croatia.[4] At the beginning of the 16-th century settlements of Orthodox Christians were also established in western Croatia.[5] In the first half of the 16-th century Serbs settled Ottoman part of Slavonia while in the second part of the 16-th century they moved to Austrian part of Slavonia.[6] In 1550 they established the Lepavina Monastery.[7] At the end of the 16th century a group of Serb Orthodox priests built a monastery dedicated to Saint Archangel Gabriel (Serbian: Манастир Светог Арханђела Гаврила) on the foundations (or near them)[8] of the deserted and destroyed Catholic Monastery of All Saints.[9]

Eparchy of Vretanija

Some scholars promoted the view that Marča, as a diocese of the Patriarchate of Peć, was established in the late 16th century (1578 or 1597).[10] This theory was used as evidence of the long-time presence of the Serb population on the northern bank of river Sava.[10]

In 1609 Serb Orthodox priests established Marča Monastery in Marča near Ivanić-Grad. In the same year the Marča Monastery became a seat of the Eparchy of Vretanija. This bishopric was the westernmost eparchy of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć. Its name was derived from Vretanija (Serbian: Вретанијски остров) which was a part of the title of the Serbian patriarch.[11] Its first bishop was Simeon Vratanja, appointed in 1609 by the Serb Orthodox patriarch Jovan to the position of bishop of all Orthodox Serbs who settled to Croatia.[12] This appointment marked establishment of the Eparchy of Vretanja in 1609 according to historian Aleksa Ivić.[13]

Establishment as Eastern Catholic Church

Being under strong pressure from Croatian clergy and state officials to recognize the jurisdiction of the Pope, and to convert the population of his bishopric to Eastern Catholicism, Simeon Vratanja visited Pope Paul V in 1611 and recognized his jurisdiction and maybe the Union of Florence as well.[14] The strongest influence to his decision had Martin Dobrović, who convinced Simeon to recognize papal jurisdiction and to accept the Eastern Catholicism.[15][16]

In November 1611, the Pope appointed Simeon as bishop of Serbs of Slavonia, Croatia and Hungary. He also granted all estates that once belonged to the Catholic Monastery of All Saints to the Marča Monastery.[17] On 21 November 1611 Marča was established as an eparchy (bishopric) of the Eastern Catholic Church,[18] having around 60,000 believers.[1]

History

Period of semi-union (1611–1670)

Simeon continued to use Slavic language, Julian calendar and maintained connection with Patriarchate of Peć.[19]

In 1642 Benedikt Vinković wrote a letter to emperor Ferdinand III to write a report about "Vlachs" (Orthodox Serbs).[20] Vinković's activities were aimed against Serb bishop of Marča, Maksim Predojević, whom he reported to the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith when Predojević refused to support the conversion of the population of his bishopric to Catholicism.[21] Vinković had intention to depose Predojević and appoint Rafael Levaković instead.[22]

In 1648 the king appointed Sava Stanislavić as bishop of the Bishopric of Marča, as wished by the Slavonian Serbs, although Petar Petretić, bishop of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Zagreb proposed another candidate.[23]

This kind of semi-union attitude of Serb bishops of the Bishopric of Marča remained until 1670 and appointment of Pavle Zorčić on the position of bishop.[24] All priests of the Bishopric of Marča who objected to the union were arrested and imprisoned in Malta where they all died.[25]

Period of union (1670–1753)

In 1754 around 17,000 Serb Uskoks rebelled in support of the Marča monastery, the seat of Uskok bishopric. The monastery was abandoned, as ordered by Empress Maria Theresa, and its treasury was looted.[26]

Bishops

The bishops of the Eparchy of Marča were:

- Simeon Vratanja (1607–1629)

- Maxim Predojević (1630–1642)

- Gabrijel Predojević (1642–1644)

- Vasilije Predojević (1644–1648)

- Sava Stanislavić (1648–1661)

- Gabrijel Mijakić (1663–1670)

- Pavao Zorčić (1671–1685)

- Marko Zorčić (1685–1688)

- Isaija Popović (1689–1699)

- Gabrijel Turčinović (1700–1707)

- Grgur Jugović (1707–1709)

- Rafael Marković (1710–1726)

- Georg Vučinić (1727–1733)

- Silvester Ivanović (1734–1735)

- Teofil Pašić (1738–1746)

- Gabrijel Palković (1751–1758)

- Vasilije Božičković (1759–1777)

References

- 1 2 Foundation 2001, p. 97.

- ↑ Letopis matice srpske. U Srpskoj narodnoj zadružnoj štampariji. 1926. p. 319.

Тако је на рушевинама српске православие епископије у Марчи створена крижевачка унијатска бискупија, која и данас постоји.

- ↑ Љушић, Радош (2008). Српска државност 19. века. Српска књижевна задруга. p. 449.

Насељавањем и подизањем цркава и манастира створени су предуслови за црквену организацију Срба, која је настала у манастиру Марчи - марчанска, ускочка или вретанщска епископија, почетком 17. века.

- ↑ (Frucht 2005, p. 535): "Population movements began in earnest after the Battle of Smederevo in 1459, and by 1483, up to two hundred thousand Orthodox Christians had moved into central Slavonia and Srijem (eastern Croatia)."

- ↑ (Frucht 2005, p. 535): "In the early sixteenth century Orthodox populations had also been established in western Croatia."

- ↑ sinod, Srpska pravoslavna crkva. Sveti arhijerejski (1972). Službeni list Srpske pravoslavne crkve. p. 55.

Тридесетих година XVI в. многи Срби из Босне су се населили у Крањској, Штајерској и Жумберку. ... Сеобе Срба у Славонију и Хрватску трајале су кроз цео XVI, XVII и XVIII в. У првој половини XVI в. су се најпре засељавали у турском делу Славоније, а у другој половини истог века су се пресељавали из турског у аустријски део Славони- је.

- ↑ sinod, Srpska pravoslavna crkva. Sveti arhijerejski (2007). Glasnik. 89. p. 290.

МАНАСТИР ЛЕПАВИНА, посвећен Ваведењу Пресвете Богородице, подигнут 1550.

- ↑ Kudelić 2002, p. 145.

- ↑ Kolarić 2002, p. 77.

- 1 2 Kudelić 2002, p. 147.

- ↑ Ćirković 2008, p. 164.

- ↑ Maković 2005, p. 12.

- ↑ Kudelić 2002, p. 148.

- ↑ Milutin Miltojević, Serbian Historiography of Union of Serbs in the 17th century, Niš University, p. 225

- ↑ Ivić 1909, p. 45.

- ↑ arhiv 1916, p. 89.

- ↑ "Манастир Марча". Metropolitanate of Zagreb and Ljubljana. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ↑ Z. Kudelić, Isusovačko izvješće o krajiškim nemirima 1658. i 1666. godine,Hrvatski institut za povijest, 2007, page 121

- ↑ Milutin Miltojević, Serbian Historiography of Union of Serbs in the 17th century, Niš University, p. 225

- ↑ tisak 1917, p. 37.

- ↑ Kašić 1967, p. 49.

- ↑ Kašić 1988, p. 144.

- ↑ Spomenica 1996, p. 74.

- ↑ Milutin Miltojević, Serbian Historiography of Union of Serbs in the 17th century, Niš University, p. 225

- ↑ Milutin Miltojević, Serbian Historiography of Union of Serbs in the 17th century, Niš University, p. 225

- ↑ Medaković 1971, p. 236.

Sources

- Dept, Central European University. History; Foundation, European Science (2001). Frontiers of faith: religious exchange and the constitution of religious identities 1400–1750. Central European University.

- Ćirković, Sima M. (2008). Srbi među europskim narodima. Golden marketing-Tehnička knjiga. ISBN 978-953-212-338-8.

- Kolarić, Juraj (2002). Povijest kršćanstva u Hrvata: Katolička crkva. Hrvatski studiji Sveučilišta u Zagrebu. ISBN 978-953-6682-45-4.

- tisak (1917). Djela Jugoslavenske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti. Tisak Dioničke tiskare.

- Kašić, Dušan Lj (1967). Srbi i pravoslavlje u Slavoniji i sjevernoj Hrvatskoj. Savez udruženja pravosl. sveštenstva SR Hrvatske.

- Damjanović, Dragan; Roksandić, Drago; Maković, Zvonko (2005). Saborna crkva Vavedenja Presvete Bogorodice u Plaškom: povijest episkopalnog kompleksa. Srpsko Kulturno Društvo Prosvjeta. ISBN 978-953-6627-77-6.

- Medaković, Dejan (1971). Putevi srpskog baroka. Nolit.

- Spomenica (1996). Spomeniža o srpskom pravoslavnom vladiǎnstvu pakračkom. Muzej Srpske Pravoslavne Črkve.

- Kašić, Dušan Lj (1988). Srpska naselja i crkve u sjevernoj Hrvatskoj i Slavoniji. Savez udruženja pravoslavnih sveštenika SR Hrvatske.

- Ivić, Aleksa (1909). Seoba srba u hrvatsku i slavoniju: prilog ispitivanju srpske prošlodti tokom 16. i 17. veka. Sremski karlovci.

- arhiv, Croatia. Drzavni (1916). Vjesnik.

- Kudelić, Zlatko (2002). Prvi marčanski grkokatolički biskup Simeon (1611–1630). Hrvatski institut za povijest, Zagreb, Republika Hrvatska.

- Frucht, Richard C. (2005). Eastern Europe: An Intruduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6.

Further reading

- Вуковић, Сава (1996). Српски јерарси од деветог до двадесетог века (Serbian Hierarchs from the 9th to the 20th Century). Евро, Унирекс, Каленић.

- Kudelić, Zlatko (2007). Marčanska biskupija: Habsburgovci, pravoslavlje i crkvena unija u Hrvatsko-slavonskoj vojnoj krajini (1611. – 1755). Hrvatski Inst. za Povijest. ISBN 978-953-6324-62-0.

- Kudelić, Zlatko (2007). Isusovačko izvješće o krajiškim nemirima 1658. i 1666. godine i o marčanskom biskupu Gabrijelu Mijakiću (1663.-1670.). Hrvatski institut za povijest.

- Kudelić, Zlatko (2004). Katoličko-pravoslavni prijepori o crkvenoj uniji i grkokatoličkoj Marčanskoj biskupiji tijekom 1737. i 1738. godine. Povijesni prilozi. 27. pp. 101–131.