Ubykh language

| Ubykh | |

|---|---|

| /tʷaxəbza/ | |

| Native to | Turkey |

| Region | Manyas, Balıkesir |

| Extinct | October 1992, with the death of Tevfik Esenç |

|

Northwest Caucasian

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

uby |

| Glottolog |

ubyk1235[1] |

|

Ubykh (extinct) | |

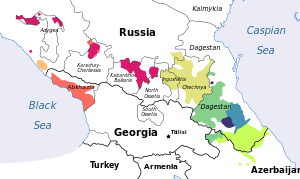

Ubykh or Ubyx is an extinct Northwest Caucasian language once spoken by the Ubykh people (who originally lived along the eastern coast of the Black Sea before migrating en masse to Turkey in the 1860s). The language's last native speaker, Tevfik Esenç, died in 1992.[2]

The Ubykh language is ergative and agglutinative, with polypersonal verbal agreement and a very large number of distinct consonants, but only two phonemically distinct vowels. With around eighty consonants it has one of the largest inventories of consonants in the world,[3] the largest number for any language without clicks.

The name Ubykh is derived from /wəbəx/, its name in the Abdzakh Adyghe language. It is known in linguistic literature by many names: variants of Ubykh, such as Ubikh, Ubıh (Turkish) and Oubykh (French); and Pekhi (from Ubykh /tʷaχə/) and its Germanised variant Päkhy.

Major features

Ubykh is distinguished by the following features, some of which are shared with other Northwest Caucasian languages:

- It is ergative, making no syntactic distinction between the subject of an intransitive sentence and the direct object of a transitive sentence. Split ergativity plays only a small part, if at all.

- It is highly agglutinative, using mainly monosyllabic or bisyllabic roots, but with single morphological words sometimes reaching nine or more syllables in length: /aχʲazbatɕʼaʁawdətʷaajlafaqʼajtʼmadaχ/ ('if only you had not been able to make him take [it] all out from under me again for them'). Affixes rarely fuse in any way.

- It has a simple nominal system, contrasting just four noun cases, and not always marking grammatical number in the direct case.

- Its system of verbal agreement is quite complex. English verbs must agree only with the subject; Ubykh verbs must agree with the subject, the direct object and the indirect object, and benefactive objects must also be marked in the verb.

- It is phonologically complex as well, with 84 distinct consonants (four of which, however, appear only in loan words). According to some linguistic analyses, it only has two phonological vowels, but these vowels have a large range of allophones because the range of consonants which surround them is large.

Phonology

Ubykh has 84 phonemic consonants, a record high amongst languages without click consonants, but only 2 phonemic vowels. Four of these consonants are found only in loanwords and onomatopoeia. There are nine basic places of articulation for the consonants and extensive use of secondary articulation, such that Ubykh has 20 different uvular phonemes. Ubykh distinguishes three types of postalveolar consonants: apical, laminal, and laminal closed. Regarding the vowels, even though there are only two phonemic vowels, there is a great deal of allophony.

Grammar

Morphosyntax

Ubykh is agglutinative and polysynthetic: /ʃəkʲʼaajəfanamət/ ('we will not be able to go back'), /awqʼaqʼajtʼba/ ('if you had said it'). Ubykh is often extremely concise in its word forms.

The boundaries between nouns and verbs in Ubykh is somewhat blurred. Any noun can be used as the root of a stative verb (/məzə/ 'child', /səməzəjtʼ/ 'I was a child'), and many verb roots can become nouns simply by the use of noun affixes (/qʼa/ 'to say', /səqʼa/ 'what I say').[4][5]

Nouns

The noun system in Ubykh is quite simple. Ubykh has three noun cases (the oblique-ergative case may be two homophonous cases with differing function, thus presenting four cases in total):

- direct or absolutive case, marked with the bare root; this indicates the subject of an intransitive sentence and the direct object of a transitive sentence (e.g. /tət/ 'a man')

- oblique-ergative case, marked in -/n/; this indicates either the subject of a transitive sentence, targets of preverbs, or indirect objects which do not take any other suffixes (/məzən/ '(to) a child')

- locative case, marked in -/ʁa/, which is the equivalent of English in, on or at.

The instrumental case (-/awn(ə)/) was also treated as a case in Dumézil (1975). Another pair of postpositions, -/laaq/ ('to[wards]') and -/ʁaafa/ ('for'), have been noted as synthetic datives (e.g. /aχʲəlaaq astʷadaw/ 'I will send it to the prince'), but their status as cases is also best discounted.

Nouns do not distinguish grammatical gender. The definite article is /a/ (e.g. /atət/ 'the man'). There is no indefinite article directly equivalent to the English a or an, but /za/-(root)-/ɡʷara/ (literally 'one'-(root)-'certain') translates French un and Turkish bir: e.g. /zanajnʃʷɡʷara/ ('a certain young man').

Number is only marked on the noun in the ergative case, with -/na/. The number marking of the absolutive argument is either by suppletive verb roots (e.g. /akʷən blas/ 'he is in the car' vs. /akʷən blaʒʷa/ 'they are in the car') or by verb suffixes: /akʲʼan/ ('he goes'), /akʲʼaan/ ('they go'). Interestingly, the second person plural prefix /ɕʷ/- triggers this plural suffix regardless of whether that prefix represents the ergative, the absolutive, or an oblique argument:

- Absolutive: /ɕʷastʷaan/ ('I give you all to him')

- Oblique: /səɕʷəntʷaan/ ('he gives me to you all')

- Ergative: /asəɕʷtʷaan/ ('you all give it/them to me')

Note that, in this last sentence, the plurality of it (/a/-) is obscured; the meaning can be either 'I give it to you all' or 'I give them to you all'.

Adjectives, in most cases, are simply suffixed to the noun: /tʃəbʒəja/ ('pepper') with /pɬə/ ('red') becomes /tʃəbʒəjapɬə/ ('red pepper'). Adjectives do not decline.

Postpositions are rare; most locative semantic functions, as well as some non-local ones, are provided with preverbal elements: /asχʲawtxqʼa/ ('you wrote it for me'). However, there are a few postpositions: /səʁʷa səɡʲaatɕʼ/ ('like me'), /aχʲəlaaq/ ('near the prince').

Verbs

A past-present-future distinction of verb tense exists (the suffixes -/qʼa/ and -/awt/ represent past and future) and an imperfective aspect suffix is also found (-/jtʼ/, which can combine with tense suffixes). Dynamic and stative verbs are contrasted, as in Arabic, and verbs have several nominal forms. Morphological causatives are not uncommon. The conjunctions /ɡʲə/ ('and') and /ɡʲəla/ ('but') are usually given with verb suffixes, but there is also a free particle corresponding to each:

- -/ɡʲə/ 'and' (free particle /ve/, borrowed from Turkish);

- -/ɡʲəla/ 'but' (free particle /aʁʷa/)

Pronominal benefactives are also part of the verbal complex, marked with the preverb /χʲa/-, but a benefactive cannot normally appear on a verb that has three agreement prefixes already.

Gender only appears as part of the second person paradigm, and then only at the speaker's discretion. The feminine second person index is /χa/-, which behaves like other pronominal prefixes: /wəsχʲantʷən/ ('he gives [it] to you [normal; gender-neutral] for me'), but compare /χasχʲantʷən/ 'he gives [it] to you [feminine] for me').

Adverbials

A few meanings covered in English by adverbs or auxiliary verbs are given in Ubykh by verb suffixes:

- /asfəpχa/ ('I need to drink it')

- /asfəfan/ ('I can drink it')

- /asfəɡʲan/ ('I drink it all the time')

- /asfəlan/ ('I am drinking it all up')

- /asfətɕʷan/ ('I drink it too much')

- /asfaajən/ ('I drink it again')

Questions

Questions may be marked grammatically, using verb suffixes or prefixes:

- Yes-no questions with -/ɕ/: /wana awbjaqʼaɕ/? ('did you see that?')

- Complex questions with -/j/: /saakʲʼa wəpʼtsʼaj/? ('what is your name?')

Other types of questions, involving the pronouns 'where' and 'what', may also be marked only in the verbal complex: /maawkʲʼanəj/ ('where are you going?'), /saawqʼaqʼajtʼəj/ ('what had you said?').

Preverbs and determinants

Many local, prepositional, and other functions are provided by preverbal elements providing a large series of applicatives, and here Ubykh shows remarkable complexity. Two main types of preverbal elements exist in Ubykh: determinants and preverbs. The number of preverbs is limited, and mainly show location and direction. The number of determinants is also limited, but the class is more open; some determinant prefixes include /tʃa/- ('with regard to a horse') and /ɬa/- ('with regard to the foot or base of an object').

For simple locations, there are a number of possibilities that can be encoded with preverbs, including (but not limited to):

- above and touching

- above and not touching

- below and touching

- below and not touching

- at the side of

- through a space

- through solid matter

- on a flat horizontal surface

- on a non-horizontal or vertical surface

- in a homogeneous mass

- towards

- in an upward direction

- in a downward direction

- into a tubular space

- into an enclosed space

There is also a separate directional preverb meaning 'towards the speaker': /j/-, which occupies a separate slot in the verbal complex. However, preverbs can have meanings that would take up entire phrases in English. The preverb /jtɕʷʼaa/- signifies 'on the earth' or 'in the earth', for instance: /ʁadja ajtɕʷʼaanaaɬqʼa/ ('they buried his body'; literally, "they put his body in the earth"). Even more narrowly, the preverb /faa/- signifies that an action is done out of, into or with regard to a fire: /amdʒan zatʃətʃaqʲa faastχʷən/ ('I take a brand out of the fire').

Orthography

Writing systems for the Ubykh language have been proposed,[6] but there has never been a standard written form.

Lexicon

Native vocabulary

Ubykh syllables have a strong tendency to be CV, although VC and CVC also exist. Consonant clusters are not as large as in Abzhywa Abkhaz or in Georgian, rarely being larger than two terms. Three-term clusters exist in two words - /ndʁa/ ('sun') and /psta/ ('to swell up'), but the latter is a loan from Adyghe, and the former more often pronounced /nədʁa/ when it appears alone. Compounding plays a large part in Ubykh and, indeed, in all Northwest Caucasian semantics. There is no verb equivalent to English to love, for instance; one says "I love you" as /tʂʼanə wəzbjan/ ('I see you well').

Reduplication occurs in some roots, often those with onomatopoeic values (/χˤaχˤa/, 'to curry[comb]' from /χˤa/ 'to scrape'; /kʼərkʼər/, 'to cluck like a chicken' [a loan from Adyghe]); and /warqwarq/, 'to croak like a frog').

Roots and affixes can be as small as one phoneme. The word /wantʷaan/, 'they give you to him', for instance, contains six phonemes, each a separate morpheme:

- /w/ - 2nd singular absolutive

- /a/ - 3rd singular dative

- /n/ - 3rd ergative

- /tʷ/ - to give

- /aa/ - ergative plural

- /n/ - present tense

However, some words may be as long as seven syllables (although these are usually compounds): /ʂəqʷʼawəɕaɬaadətʃa/ ('staircase').

Slang and idioms

As with all other languages, Ubykh is replete with idioms. The word /ntʷa/ ('door'), for instance, is an idiom meaning either "magistrate", "court", or "government." However, idiomatic constructions are even more common in Ubykh than in most other languages; the representation of abstract ideas with series of concrete elements is a characteristic of the Northwest Caucasian family. As mentioned above, the phrase meaning "I love you" translates literally as 'I see you well'; similarly, "you please me" is literally 'you cut my heart'. The term /wərəs/ ('Russian'), a Turkish loan, has come to be a slang term meaning "infidel", "non-Muslim" or "enemy" (see History below).

Foreign loans

The majority of loanwords in Ubykh are derived from either Adyghe or Turkish, with smaller numbers from Persian, Abkhaz, and the South Caucasian languages. Towards the end of Ubykh's life, a large influx of Adyghe words was noted; Vogt (1963) notes a few hundred examples. The phonemes /ɡ/ /k/ /kʼ/ were borrowed from Turkish and Adyghe. /ɬʼ/ also appears to come from Adyghe, although it seems to have arrived earlier on. It is possible, too, that /ɣ/ is a loan from Adyghe, since most of the few words with this phoneme are obvious Adyghe loans: /paaɣa/ ('proud'), /ɣa/ ('testis').

Many loanwords have Ubykh equivalents, but were dwindling in usage under the influence of Turkish, Circassian, and Russian equivalents:

- /bərwə/ ('to make a hole in, to perforate' from Turkish) = /pɕaatχʷ/

- /tʃaaj/ ('tea' from Turkish) = /bzəpɕə/

- /wərəs/ ('enemy' from Turkish) = /bˤaqˤʼa/

Some words, usually much older ones, are borrowed from less influential stock: Colarusso (1994) sees /χˤʷa/ ('pig') as a borrowing from a proto-Semitic *huka, and /aɡʲarə/ ('slave') from an Iranian root; however, Chirikba (1986) regards the latter as being of Abkhaz origin ( ← Abkhaz agər-wa 'lower cast of peasants; slave', literally 'Megrelian').

Evolution

In the scheme of Northwest Caucasian evolution, despite its parallels with Adyghe and Abkhaz, Ubykh forms a separate third branch of the family. It has fossilised palatal class markers where all other Northwest Caucasian languages preserve traces of an original labial class: the Ubykh word for 'heart', /ɡʲə/, corresponds to the reflex /ɡʷə/ in Abkhaz, Abaza, Adyghe, and Kabardian. Ubykh also possesses groups of pharyngealised consonants. All other NWC languages possess true pharyngeal consonants, but Ubykh is the only language to use pharyngealisation as a feature of secondary articulation.

With regard to the other languages of the family, Ubykh is closer to Adyghe and Kabardian but shares many features with Abkhaz due to geographic influence; many later Ubykh speakers were bilingual in Ubykh and Adyghe.

Dialects

While not many dialects of Ubykh existed, one divergent dialect of Ubykh has been noted (in Dumézil 1965:266-269). Grammatically, it is similar to standard Ubykh (i.e. Tevfik Esenç's dialect), but has a very different sound system, which had collapsed into just 62-odd phonemes:

- /dʷ/ /tʷ/ /tʷʼ/ have collapsed into /b/ /p/ /pʼ/.

- /ɕʷ/ /ʑʷ/ are indistinguishable from /ʃʷ/ /ʒʷ/.

- /ɣ/ seems to have disappeared.

- Pharyngealisation is no longer distinctive, having been replaced in many cases by geminate consonants.

- Palatalisation of the uvular consonants is no longer phonemic.

History

Ubykh was spoken in the eastern coast of the Black Sea around Sochi until 1864, when the Ubykhs were driven out of the region by the Russians. They eventually came to settle in Turkey, founding the villages of Hacı Osman, Kırkpınar, Masukiye and Hacı Yakup. Turkish and Circassian eventually became the preferred languages for everyday communication, and many words from these languages entered Ubykh in that period.

The Ubykh language died out on 7 October 1992, when its last fluent speaker (Tevfik Esenç) died in his sleep.[2] Before his death, thousands of pages of material and many audio recordings had been collected and collated by a number of linguists, including Georges Charachidzé, Georges Dumézil, Hans Vogt, George Hewitt and A. Sumru Özsoy, with the help of some of its last speakers, particularly Tevfik Esenç and Huseyin Kozan.[2] Ubykh was never written by its speech community, but a few phrases were transcribed by Evliya Celebi in his Seyahatname and a substantial portion of the oral literature, along with some cycles of the Nart saga, was transcribed. Tevfik Esenç also eventually learned to write Ubykh in the transcription that Dumézil devised.

Julius von Mészáros, a Hungarian linguist, visited Turkey in 1930 and took down some notes on Ubykh. His work Die Päkhy-Sprache was extensive and accurate to the extent allowed by his transcription system (which could not represent all the phonemes of Ubykh) and marked the foundation of Ubykh linguistics.

The Frenchman Georges Dumézil also visited Turkey in 1930 to record some Ubykh and would eventually become the most celebrated Ubykh linguist. He published a collection of Ubykh folktales in the late 1950s, and the language soon attracted the attention of linguists for its small number (two) of phonemic vowels. Hans Vogt, a Norwegian, produced a monumental dictionary that, in spite of its many errors (later corrected by Dumézil), is still one of the masterpieces and essential tools of Ubykh linguistics.

Later in the 1960s and into the early 1970s, Dumézil published a series of papers on Ubykh etymology in particular and Northwest Caucasian etymology in general. Dumézil's book Le Verbe Oubykh (1975), a comprehensive account of the verbal and nominal morphology of the language, is another cornerstone of Ubykh linguistics.

Since the 1980s, Ubykh linguistics has slowed drastically. No other major treatises have been published; however, the Dutch linguist Rieks Smeets is currently trying to compile a new Ubykh dictionary based on Vogt's 1963 book, and a similar project is also underway in Australia. The Ubykh themselves have shown interest in relearning their language.

The Abkhaz writer Bagrat Shinkuba's historical novel Bagrat Shinkuba. The Last of the Departed treats the fate of the Ubykh people.

People who have published literature on Ubykh include

- Brian George Hewitt

- Catherine Paris

- Christine Leroy

- Georg Bossong

- Georges Dumézil

- Hans Vogt

- John Colarusso

- Julius von Mészáros

- Rieks Smeets

- Rohan Fenwick

- Tevfik Esenç

- Viacheslav Chirikba

- Wim Lucassen

Notable characteristics

Ubykh has been cited in the Guinness Book of Records (1996 ed.) as the language with the most consonant phonemes, although it may have fewer than some of the Khoisan languages. It has 20 uvular and 29 pure fricative phonemes, more than any other known language.

Samples of Ubykh

All examples from Dumézil 1968.[7]

- Faːχe tʼqʼokobʒa kʼeʁən azaχeʃənan amʁen ɡikeqʼan.

- 'Once, two men set out together on the road.'

- Afoːtənə mʁøːəf aχodoːtən akenan, azan fatɕʼaːla ɕubˤaːla χodaqʼa,

- 'They went to buy some provisions for the journey; the one bought cheese and bread'

- Eːdəχəŋɡi ɕobˤaːla psaːla χodan eːnuːqʼa.

- 'and the other bought bread and fish.'

aajdə-χə-n-ɡʲə ɕʷəbˤa-aala psa-aala χʷada-n a-j-nə-w-qʼa other-of-ERG-and bread-and fish-and buy-ADV it-hither-he-bring-past

- Amʁen ɡikenaɡi

- 'While they were on the road,'

a-mʁʲa-n ɡʲə-kʲa-na-ɡʲə the-road-OBL on-enter(PL)-PL-GER

- Wafatɕʼdəχodaqʼeːtʼə ʁakʼeʁʁaːfa, "ɕuʁoɬa psa jeda ɕʷfaːn;"

- 'the one who had bought the cheese asked the other, "You people eat a lot of fish;"'

- "Saːba wanaŋɡʲaːfə psa ɕʷfaːniː?" qʼan ʁaːdzʁaqʼa.

- '"why do you eat fish as much as that?"'

saaba wana-n-ɡʲaafə psa ɕʷ-f-aa-nə-j qʼa-n ʁa-aa-dzʁa-qʼa why that-OBL-as.much.as fish you.all-eat-PL-PRES-QU say-ADV him-to-ask-past

- "Psa wufəba wutɕʼa jeda ʃoːt,"

- '"If you eat fish, you get smarter,"'

psa wə-fə-ba wə-tɕʼa jada ʃ-awt fish you-eat-if your-knowledge much become-FUT

- "Wonaʁaːfa ʃəʁoɬa psa jeda ʃfən," qʼaqʼa.

- '"so we eat a lot of fish," he answered.'

wana-ʁaafa ʃəʁʷaɬa psa jada ʃ-fə-n qʼa-qʼa that-for we fish much we-eat-PRES say-PAST

See also

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Ubykh". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 1 2 3 E. F. K. Koerner (1 January 1998). First Person Singular III: Autobiographies by North American Scholars in the Language Sciences. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 978-90-272-4576-2.

- ↑ Charles King, The Ghost of Freedom (2008) p 15

- ↑ Dumézil, G. 1975 Le verbe oubykh: études descriptives et comparatives (The Ubykh Verb: Descriptive and Comparative Studies). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale

- ↑ Hewitt, B. G. 2005 North-West Caucasian. Lingua 115: 91-145.

- ↑ Fenwick, R. S. H. (2011). A Grammar of Ubykh. Munich: Lincom Europa.

- ↑ http://lacito.vjf.cnrs.fr/archivage/tools/show_text.php?id=crdo-UBY_POISSON_SOUND

Bibliography

- Viacheslav Chirikba (1986). Abxazskie leksicheskie zaimstvovanija v ubyxskom jazyke (Abkhaz Lexical Loans in Ubykh). Problemy leksiki i grammatiki jazykov narodov Karachaevo-Cherkesii: Sbornik nauchnyx trudov (Lexical and Grammatical Problems of the Karachay-Cherkessian National Languages: A Scientific Compilation). Cherkessk, 112-124.

- Viacheslav Chirikba (1996). Common West Caucasian. The Reconstruction of its Phonological System and Parts of its Lexicon and Morphology. Leiden: CNWS Publications.

- Colarusso, J. (1994). Proto-Northwest Caucasian (Or How To Crack a Very Hard Nut). Journal of Indo-European Studies 22, 1-17.

- Dumézil, G. (1961). Etudes oubykhs (Ubykh Studies). Paris: Librairie A. Maisonneuve.

- Dumézil, G. (1965). Documents anatoliens sur les langues et les traditions du Caucase (Anatolian Documents on the Languages and Traditions of the Caucasus), III: Nouvelles études oubykhs (New Ubykh Studies). Paris: Librairie A. Maisonneuve.

- Dumézil, G. (1968). Eating Fish Makes You Clever. Annotated recording available via .

- Dumézil, G. (1975). Le verbe oubykh: études descriptives et comparatives (The Ubykh Verb: Descriptive and Comparative Studies). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hewitt, B. G. (2005). North-West Caucasian. Lingua. 115, 91-145.

- Mészáros, J. von. (1930). Die Päkhy-Sprache (The Ubykh Language). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Vogt, H. (1963). Dictionnaire de la langue oubykh (Dictionary of the Ubykh Language). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

External links

- Two proposals for a practical orthography for Ubykh

- YouTube: Tevfik Esenç narrating the story of the two travellers and the fish in Ubykh

- A number of narrations by Tevfik Esenç, WAV format

- Ubykh word list and recordings