Bound variable pronoun

A bound variable pronoun (also called a bound variable anaphor or BVA) is a pronoun that has a quantified determiner phrase (DP) – such as every, some, or who – as its antecedent.[1]

An example of a bound variable pronoun in English is given in (1).

(1) Each manager exploits the secretary who works for him.

(Reinhart, 1983: 55 (19a))

In (1), the quantified DP is each manager, and the bound variable pronoun is him. This pronoun is a bound variable pronoun because it does not refer to one single entity in the world. Rather, its reference varies depending on which entities are encompassed by the phrase each manager. For example, if each manager encompasses both John and Adam, then him will refer variably to both John and Adam. The meaning of this sentence in this case would then be:

(2) John1 exploits the secretary who works for him1, and Adam2 exploits the secretary who works for him2.

(Adapted from Reinhart, 1983: 55 (19a))

where him first refers to John, and then to Adam.

In linguistics, the occurrence of bound variable pronouns is important for the study of the syntax and semantics of pronouns. Semantic analyses focus on the interpretation of the quantifiers. Syntactic analyses focus on issues relating to co-indexation, binding domain, and c-command.

Semantics: quantifier interpretation

Semantics is the branch of linguistics that examines the meaning of natural language, the notion of reference and denotation, and the concept of possible worlds. One concept used in the study of semantics is predicate logic, which is a system that uses symbols and alphabet letters to represent the overall meaning of a sentence. Quantifiers in semantics – such as the quantifier in the antecedent of a bound variable pronoun – can be expressed in two ways. There is an existential quantifier, ∃, meaning some. There is also a universal quantifier, ∀, meaning every, each, or all. Ambiguity arises when there are multiple quantifiers in one sentence.

An example of the use of quantifiers is shown in (3).

(3) Every man thinks he is intelligent.

= ∀x(man(x)): x thinks x is intelligent. (bound)

= For every man x, x thinks x is intelligent.

≠ Every man thinks every man is intelligent.

(Carminati, 2002: 2(3a))

In this example, the quantified determiner phrase every man can be expressed in predicate logic as a universal quantifier. Because of this, he refers universally and variably to each man, rather than to a single specific man.

Syntax

Syntax is the branch of linguistics that deals with the formation and structure of a sentence in natural language. It is descriptive, meaning it is concerned with how language is actually used, spoken, or written by its users, unlike prescriptive grammar/prescription which is concerned with teaching people the "correct way" to speak.

There are three main aspects of syntax that are important to the study of bound variable pronouns. These are:

- Co-indexation of a pronoun and its antecedent

- C-command relationship between the antecedent and the pronoun

- Binding domain of the pronoun

Co-indexation

According to the indexing theory,[2] each phrase in a sentence can be given a unique index, which is a number (or letter) that identifies that phrase as picking out a particular entity in the world. It is possible to modify the indexes on these phrases so that two or more phrases have the same index. This is called co-indexation. If co-indexation occurs, the phrases with the same-numbered index will all refer to the same entity. This phenomenon is called co-reference.

An example of co-indexation and co-reference is shown in (4).

(4) (a) *[Mary]i likes [herself]j

(b) [Mary]i likes [herself]i

(adapted from Sportiche et al., 2014: 161 (8a))

In (4a), the determiner phrases – Mary and herself – are each given a unique index. In (4b), co-indexing takes place, and herself changes its index to be the same as the one that Mary has. Because of this, Mary and herself now refer to the same entity in this sentence.

C-command

If a pronoun has a quantified expression as antecedent, the pronoun must be c-commanded by this antecedent.[3][4] An antecedent c-commands a pronoun if, when observing the structure of the sentence, a sister of the antecedent dominates the pronoun.[5]

The c-command relationship can be shown by drawing a tree for the sentence. Take, for instance, the following tree diagram for example (4b).

Here, Mary is the antecedent, and herself is the pronoun. The sister of Mary is the T' node, and this node dominates herself. So Mary c-commands herself in this instance.

When discussing bound variable pronouns, the pronoun is said to be bound if it is c-commanded by the quantified determiner phrase that is its antecedent.[6]

Binding domain

The domain of a determiner phrase is defined as "the smallest XP with a subject that contains the DP".[7] This domain is illustrated in the picture below.

The way a DP can bind given this domain depends on the kind of that DP that is being bound. Anaphors (reflexives pronouns like herself and reciprocals like each other) must be bound in their domain, meaning they must have a c-commanding antecedent in their domain. Pronouns (such as she or he) must not be bound in their domain, meaning they cannot have a c-commanding antecedent in their domain. Finally, R-expressions (such as proper names, descriptions, or epithets) must not be bound, meaning they must not have a c-commanding antecedent at all.[8]

When determining the binding possibilities of a bound variable pronoun, in addition to the above conditions, the bound variable pronoun must also be c-commanded by the quantified determiner phrase that is its antecedent.[9]

Theories

Higginbotham's (1980) indexing theory

One theory used to describe pronominal binding is to use index marking rules to determine possible bindings.[2][10] Index marking rules are rules used to determine which parts of a sentence carry the same reference. Each element in a sentence is given an index, which is a unique identifier of that element. A set of rules can then be applied to modify the index of one element to be the same as the index of another. Those two elements will then share the same index, and so will refer to the same thing. This indexing theory was used as a way to describe pronominal binding by Noam Chomsky, and expanded upon by James Higginbotham. The theory holds that the binding of pronouns consists of three main parts.

- There are coindexing rules that assign unique indexes to the elements in a sentence.

- There are contraindexing rules, which create a list of indexes for which an element cannot hold a reference.

- There are deletion/reindexing rules, which are rules used to allow some previously prohibited references to occur, and which modify index numbers of certain elements to be the same as another element and allow these two elements to refer to the same entity.[10]

Co-indexing and contra-indexing

In the coindexing stage,[11] each noun phrase is given a unique index, called a "referential index". In the contraindexing[12] stage, each non-anaphoric noun phrase (i.e. each noun phrase that is not a reflexive pronoun like "herself" or a reciprocal pronoun like "each other") is given a set of "anaphoric indices". This set consists of the referential indices of all elements that c-command it. This set of anaphoric indices is used to determine whether coreference can occur between two noun phrases. In order for coreference to occur, neither noun phrase can contain the other's referential index in its set of anaphoric indices. For example, in sentence (5):

(5) Johni,Φ saw himj,{i}.

(Higginbotham, 1980: 682 (15)) |

.png) "John saw him", adapted from Higginbotham, 1980: 682 (15), drawn using phpSyntaxTree |

"John" has a referential index of i, but its anaphoric index is empty, since it is not c-commanded by anything. "Him" has a referential index of j, and its set of anaphoric indices contains only i, because "John" c-commands "him". Since the set of anaphoric indices for "him" contains i, "John" and "him" cannot be coreferenced, which is expected in this sentence.[12]

Deletion rules must then be applied to account for sentences with permissible coreference such as (6):

(6) John thinks he's a nice fellow. (Higginbotham, 1980: 682 (16)) |

.png) "John thinks he is a nice fellow", adapted from Higginbotham, 1980: 682 (16), drawn using phpSyntaxTree |

The deletion rule, as broadly stated by Chomsky,[13] can be focused to pronouns as Higginbotham describes:

If B is a pronoun that is free(i) in the minimal X = S or NP containing B and B is either: (a) nominative; or, (b) in the domain of the subject of X, then i deletes from its anaphoric index. (Higginbotham, 1980: 682–683 (18))

Where a "pronoun B is free(i) in X iff it occurs in X and there is nothing in X with the referential index i that c-commands B".[14]

Reindexing rules

Once the appropriate indices are determined, bound variable pronouns can be coreferenced with their antecedents, where possible, by applying a set of reindexing rules. During this process, when one element is reindexed, all other elements with the same initial referential index will also be reindexed.[15] Reindexing can also occur between a pronoun and a trace or PRO element, as follows:

In a configuration: ... ei... pronounj reindex j to i. (Higginbotham, 1980: 689 (55))

Where ei is a trace or PRO element.[16]

This reindexing rule is constrained by what Higginbotham calls the "C-Constraint",[17] which states that reindexing cannot cause the following pattern to occur in the Logical Form of the sentence:

...[NP...ei...]j...pronouni...ej... (Higginbotham, 1980: 693 (C))

For example, a sentence such as:

(7) it2s climate is hated by [everybody in some city]4]3

(Higginbotham, 1980: 693 (84))

would have the Logical Form:

(8) [some city]4 [everybody in e4]3 it2s climate is hated by e3

(Higginbotham, 1980: 693 (85))

In the Logical Form, the Noun Phrase everybody in some city is one logical unit, and the noun phrase some city is another. These phrases are unfolded and brought to the front of the form, leaving their (identically-indexed) traces behind to show where they would appear in the sentence. Without the C-constraint proposed above, applying the reindexing rule to this Logical Form would allow it2 to be reindexed to it4,[17] resulting in the form:

(9) [some city]4 [everybody in e4]3 it4s climate is hated by e3

(adapted from Higginbotham, 1980: 693 (85))

This sentence, when reindexed, is supposed to carry the same meaning as "everybody in some city hates its climate",[17] but does not do so correctly. With the C-Constraint in place, it2 would not be allowed to reindex to it4 which, Higginbotham claims, is what speakers of English would expect.[17]

Application to bound variable pronouns

The indexing theory is meant to explain pronoun indexing and coreference in general. When applied to bound variable pronouns, Higginbotham states that the same rules apply.[15] Take, for example, the following sentence:

(10) Everyone told someone he expected to see him.

(Higginbotham, 1980: 686 (33))

This sentence can have many different interpretations, depending on how the pronouns "he" and "him" bind. However, as Higginbotham points out, "he" and "him" cannot both refer to the same person.[15] This is due to restrictions on the reindexing rule because of the referential index and set of anaphoric indices that exist for each Noun Phrase in the sentence.[18] To see how this would be the case, the rules stated above can be applied to the sentence to determine the final binding possibilities. Applying the co-indexing rule will result in the following Logical Form, in which each Noun Phrase is given a referential index:

(11) everyone2 told someone3 [S he4 expected [S for e4 self to see him5]]

(adapted from Higginbotham, 1980: 686 (39))

Once the co-indexing step is complete, then the contra-indexing step is applied as described above, producing the Logical Form below:

(12) everyone2 told someone3,{2} [S he4{2,3} expected [S for e4 self to see him5{2,3,4}]]

(Higginbotham, 1980: 686 (39))

The deletion rules are then applied, yielding the Logical Form:

(13) everyone2 told someone3,{2} [S he4 expected [S for e4 self to see him5{4}]]

(Higginbotham, 1980: 686 (40))

At this point, reindexing rules can apply. However, Higginbotham notes,[18] if he and him reindex to the same quantifier (for example, everyone), the following form would be generated, since the indexes 4 and 5 would be reindexed to 2:

(14) everyone2 told someone3,{2} [S he2 expected [S for e2 self to see him2{2}]]

(Higginbotham, 1980: 686 (41))

This is not possible, since him has 2 as both its referential index and as part of its set of anaphoric (non co-referable) indices. Therefore, as predicted, he and him cannot bind to the same antecedent.[18] It is possible, however, to apply the reindexing rules so that he binds to everyone and him binds to someone, since the application of the reindexing rule in this case does not cause a contradiction, as exemplified below:

(15) everyone2 told someone3,{2} [S he2 expected [S for e2 self to see him3{2}]]

(adapted from Higginbotham, 1980: 686 (40))

Objections

One objection that has been made to this theory is that it is too complex.[19] While it accounts for many possible sentences, it also requires introducing new rules and constraints, and treats bound variable pronouns differently from other types of pronouns. Proponents of this objection, such as linguist Tanya Reinhart, argue that the difference between bound variable pronouns and pronouns of other kinds should be a semantic rather than a syntactic difference. They propose that a syntactic theory that requires less rules would be a more preferable theory.[19]

Reinhart's (1983) bound variable theory

Studies on anaphora focus on the conditions for definite NP anaphora and avoid the problems with interpreting pronouns.[20] Reinhart clarifies the difference between bound-variable pronouns (ie. bound-anaphora) and coreference (ie. the referential interpretation) and concludes that the bound-variable conditions apply to a number of seemingly unrelated phenomena, including reflexivization, quantified NP anaphora, and sloppy identity. She argues that the way pronouns can be interpreted and the times at which coreference cannot occur are determined by the syntax of the sentence.[21]

Coindexing conditions

Previous studies on anaphora focused on coreference instead of bound anaphora, which dictated groupings of anaphora facts in a specific way.[22] Reinhart states that previous analyses focusing primarily on coreference would determine the permissibility of examples (16)-(18) in three different ways. Group (16) would be classified as cases where definite NP coreference is allowed. Definite NP coreference would be deemed impossible in group (17). Finally, group (18) would require special treatment since it deals with cases of quantified NP anaphora.[23] By following these coreference rules, Reinhart notes that examples (16)–(18) would not constitute well-formed sentences.

(16)

(a) Felix thinks he is a genius.

(b) Felix adores himself.

(c) Those who know him despite Felix.

(Reinhart, 1983: 80 (74a-c))

(17)

(a) He thinks Felix is a genius.

(b) Felix adores him.

(Reinhart, 1983: 80 (75a-b))

(18) * Those who know him despite every manager.

(Reinhart, 1983: 80 (76))

However, Reinhart argues that it is due to these analyses that problems with the current anaphora theory arise. She suggests that once the focus is shifted from coreference to bound anaphora, it would appear that the sentences groups in (16)–(18) would "not constitute grammatical or sentence-level classes."[24]

Reinhart points out that the main distinction is in (16a) and (16b) where bound anaphora is possible. She suggests that the "pronoun can be translated as a bound variable," and that in all the other sentences, it cannot.[25]

The coreference differences between the sentences that do not allow bound anaphora come from semantic and pragmatic considerations from outside the syntax. Reinhart states that with the sloppy-identity test, "the distinction between bound anaphora and coreference in the case of definite NPs is not arbitrary."[25]

In previous analyses, phenomena such as reflexivisation, quantified NP anaphora, and sloppy identity were treated as separate mechanisms. However, Reinhart states that clarifying the distinction between bound anaphora and coreference allows us to observe that these mechanisms are "all instances of the same phenomenon" and that they "observe the same bound-anaphora conditions."[25]

From her analysis, Reinhart proposes a rule that captures anaphora as a mechanism which she argues is "governing the translation of pronouns as bound variables."[25]

(19) Coindex a pronoun P with a c-commanding NP α (α not immediately dominated by COMP or S')

conditions:

(a) if P is an R-pronoun α must be in its minimal governing category (MGC).

(b) if P is non-R-pronoun α must be outside its minimal governing categories (MGC)

(Reinhart, 1984: 158–159 (34a-b))

Here, an R-pronoun is a reflexive pronoun (like herself) or reciprocal pronoun (like each other).[26] The minimal governing category (or MGC) is defined, broadly, as the smallest category that contains both the pronoun and a governor of that pronoun.[27]

Reinhart then provides examples where rule (19) is optional and "no special obligatory requirement on R-pronouns is needed."[25] This is because R-pronouns can only ever be interpreted as bound variables. Because only coindexed pronouns are able to be interpreted in this way, then if an R-pronoun becomes uncoindexed, the sentence that arises as a result of this derivation will be uninterpretable.[28]

(20)

(a) Everyonei respects himselfi.

(b) Felixi thinks that hei is a genius.

(c) In hisi drawer each of the managersi keeps a gun.

(Reinhart, 1984: 159 (35a–c))

(21)

(a) Zelda bores her.

(b) He thinks that Felix is a genius.

(c) Felix thinks that himself is a genius.

(d) Those who know her respect Zelda.

(e) Those who know her respect no presidents' wife.

(Reinhart, 1984: 159 (36a–e))

Based on Reinhart's theory, the pronouns in group (20) can all be coindexed within their respective sentences. In contrast, the pronouns in group (21) are unable to be coindexed because none of the sentences meets the coindexing conditions.[28]

(21a) does not meet the coindexing condition of (19b) because the condition does not allow non-R-pronouns to be coindexed within their MGC. (21b, d, and e) are unable to be coindexed because the pronouns are not c-commanded by the potential antecedent. (21c)'s R-pronouns cannot be coindexed with NPs outside their MGC. Thus, the pronouns in the sentences in group (21) are uninterpretable as bound variables.[28]

Only in cases of “genuinely quantified NP’s” is bound anaphora feasible because bound anaphora cannot involve reference or coreference.

Kratzer (2009)

Introduction

Angelika Kratzer introduced the idea that fake indexicals are ambiguous between bound variable pronouns and a referential interpretation, creating a theory where a pronoun must be formed with feature transmission from a v in a vP. There are cases where a feature is not required to bind a bound variable pronoun to a v, but in these situations, the pronoun in question must have been referential and fully produced with all features.[29]

Theory

Kratzer brings up the topic of an embedded vP, which can be roughly defined as a verb phrase that projects a predicate that ends up "reflexivized". "Reflexivized", as defined by Kratzer, is when a pronoun bound from v and an argument introduced by v have coreferential or covarying interpretations.[29]

(22) (a) I talked about myself. (b) I blamed myself. (Kratzer, 2009: 194 (15))

Minimal pronouns require closeness to a vP, often with an embedded possessive. An embedded v would start with a relative pronoun in specifier position, which would later be followed by a bound variable interpretation. Locality domains for reflexives are first determined by the proximity of indexicals, myself, to v. Previously thought of as indexicals, the subject pronoun myself can be instead attributed to being bound pronouns connected to the closest v.[29]

In English, bound variable pronouns are grammatical in some situations while in German they are not (see the section on German below).

(23) (a) ?I am the only one who has brushed my teeth. (b) ?You are the only one who has brushed your teeth. (c) We are the only ones who have brushed our teeth. (d) You are the only ones who have brushed your teeth. (Kratzer, 2009: 202 (27))

(23a) and (23b) are determined to be grammatically correct, but an issue arises from the bound variable standpoint. Due to a third person inflective, the bound variable readings for (23a) and (23b) should be considered impossible, but as Kratzer states, they are considered to be correct. This can be attributed to how the third person inflection is not supposed to be associated with a possessive first or second person bound variable pronoun.[29]

Expanding slightly from (23), Kratzer gives the example:

(24) We are the only people who brush our teeth. (Kratzer, 2009: 202 (28))

In this example, the v, what normally binds the pronoun, has all phi features bound to itself from the start. Kratzer describes predication as the subject pronoun that eventually becomes a relative pronoun. Predication, in (24) adopts the phi features from v. Kratzer predicts that the merging of DPs to a specifier position would only happen when the DPs are without phi features. In the event that a DP adopts phi features from v from predication, then there should be a clear distinction.[29]

Kratzer illustrates this point by providing the following example:

(25) *Nina v respects myself. (Kratzer, 2009: 205 (20))

(25) is deemed ungrammatical because it has a third person and first person feature. The third person feature, "Nina", marks the sentence as ungrammatical due to how it specifies a person. English does not accept third person features in sentences when first person features already exist. German, however, does, which is explained in the German section below.[29]

Leading off of (25)'s inability to have third and first person features, Kratzer builds on the idea that third person features may be gender features instead of person features. The subset principle, which determines that a word can be inserted into a position it may not belong in as long as subsets of the features in the position match the word, allows the introduction of first, second or third person features in relative pronouns. First, second, and third person features can thus have gender features, which in turn would account for a verbal agreement that requires the word following subset principle to obey.[29]

(26) I am the only one who takes care of her children (Kratzer, 2009: 207 (38))

(26) has a feature combination with third person possessives aligning with third person verbal agreement, creating a grammatical sentence.[29]

Data

English

Weak Crossover

While bound variable pronouns fall into the category of anaphora, there are cases in which bound variable pronouns behave differently from regular anaphora. Take, for instance, the examples below, as presented by Reinhart.

(27)(a) The secretary that works for him despises Siegreied.

(b) *The secretary who works for him despises {a manager/each manager}

(c) *Who does the secretary who works for him despise t

(Reinhart, 1983: 55 (16))

In (27a), the pronoun him is able to be interpreted as being coreferential with Siegreied. However, in (27b), the same pronoun him is not able to be interpreted as being coreferential with either a manager or each manager. The difference between these two sentences is only that the DP Siegreied is replaced with a quantified DP. Likewise, when Siegreied is replaced with the wh-expression who as in (27c), the coreferential interpretation is again not possible.[30]

Reinhart is quick to point out that the difference in available interpretations is not because the Logical Form of these sentences is impossible to describe. To prove this, she provides an interpretation of these sentences in symbolic logic, shown below.[30]

(28) {Each x: x a manager/Which x: x a manager} the secretary who works for x despises x

(Reinhart, 1983: 55 (17))

This is the meaning that is trying to be expressed in (27a)–(27c), these forms are not able to properly capture this meaning.[31] The problem seen here is called "weak crossover".[30]

Problems with c-command restriction

Another difficulty faced in determining a theory of anaphora that properly encompasses bound variable pronouns is properly determining the definition of bound. As previously stated, a bound variable pronoun is said to be bound if it is c-commanded by its antecedent. In many cases, this definition makes correct predictions about the availability of bound variable interpretations. However, as in the example below, this requirement does not always seem to work.

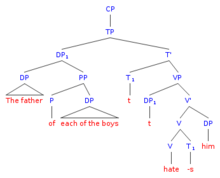

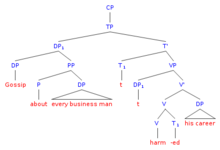

(29)(a) The father of each of the boys hates him

(b) Gossip about every business man harmed his career

(Reinhart, 1983: 56 (20)) |

Simplified syntax tree adapted from Reinhart (1983) example 20a, made with phpSyntaxTree |

Simplified syntax tree adapted from Reinhart (1983) example 20b, made with phpSyntaxTree |

In both of these instances, Reinhart claims that most people will find co-reference (and a "bound variable" interpretation) permissible.[32] However, in each case the quantified DP does not in fact c-command the pronoun, as shown in the tree diagrams for these sentences. Reinhart proposes that we need to create a theory of anaphora that accounts for cases such as these.[32]

Issues with adjoined prepositional phrases

Similar to the problem with c-command stated above, issues with binding arise when the antecedent appears within a prepositional phrase (PP). Reinhart illustrates this problem with the following example.

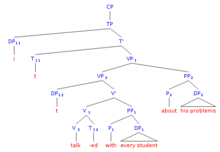

(30) I talked with every studenti about hisi problems

(Reinhart, 1983: 82 (Appendix (4a))) |

In this case, and cases like it, the antecedent does not c-command the pronoun. This is clearly visible in the tree structure provided for this sentence. Regardless of the lack of c-command, the "bound variable" interpretation is nonetheless permissible. This yet again illustrates that there are problems with the current definition of binding.[33]

Mandarin Chinese

Similarities to English

Mandarin Chinese contains bound variable pronouns that behave similarly to bound variable pronouns in English in some ways.

(31) Shei kanjyan ta muchin?

who see he mother (emphasis added)

'Who sees his mother?' (adapted, emphasis added)

(Higginbotham, 1980: 695 (94)) |

Simplified syntax tree adapted from Higginbotham (1980) example 94, made with phpSyntaxTree |

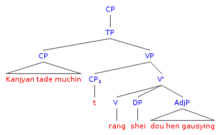

(32) Kanjyan tade muchin rang shei dou hen gausying. (emphasis added)

see his mother make everyone very happy

'Seeing his mother made everyone very happy.' (emphasis added)

(Higginbotham, 1980: 695 (96)) |

Simplified syntax tree adapted from Higginbotham (1980) example 96, made with phpSyntaxTree |

Example (31) can be interpreted as "Who sees his mother", in which who and his refer to the same person.[34]

In example (32), his is able to either refer either an unnamed third party, or to co-refer with everyone.[35] This leads to an ambiguity, in which the second interpretation is the bound variable interpretation.

Quantifier scope adverb "dou"

As in English, the quantifier must have scope over the pronoun in order to permit a bound variable interpretation.[36] Mandarin uses the scope adverb dou (or all) to denote the scope of certain noun phrases.[36] Compare, for instance, examples (33) and (34) below:

(33) [NP [S meige reni shoudao] de xin] shangmian dou you tai taitai de mingzi.

every man receive DE letter top all have he wife DE name

'For every person x, letters that x received have x's wife's name on them.'

(Huang, 1982: 409 (206a))

(34) *[NP [S meige reni dou shoudao] de xin] shangmian you tai taitai de mingzi.

every man all receive DE letter top have he wife DE name

*'Letters that everybodyi received have hisi wife's name on them.'

(Huang, 1982: 409 (206b))

In example (33), the scope adverb occurs outside of the Quantified Noun Phrase every man, which permits this quantifier to have scope over the entire sentence, thus allowing it to c-command the pronoun ta (or he). This allows he to be interpreted as a variable bound to the quantifier phrase every man.[36] In contrast, in example (34) the scope adverb occurs within the Quantified Noun Phrase, causing the quantifier to only have scope over that noun phrase. It therefore cannot c-command the pronoun ta, and so the pronoun cannot be interpreted as a variable bound to the quantifier.[36]

CC-constraint

There are cases in which Mandarin Chinese appears to differ from English with respect to pronouns being able to be interpreted as bound variables. Take, for instance, example (35):

(35) Shei de muchin dou kanjyan ta.

who mother all see him (adapted, emphasis added)

'Everyone's mother saw him.' (emphasis added)

(Higginbotham, 1980: 696(98)) |

Simplified syntax tree adapted from Higginbotham (1980) example 98, made with phpSyntaxTree |

Here, him cannot be co-referenced with everyone and must refer to another person. This differs from the English interpretation which can allow him to refer as a bound variable to whichever person everyone selects. Higginbotham claims that this is due to Mandarin Chinese having stronger constraints on reindexing than English in general.[35] He suggests that, in Mandarin, the following form cannot be created by the reindexing rules:

... [NP...ei...]j...pronouni... (Higginbotham, 1980: 696(CC))

Here, the ei is a trace element. This constraint is called the "CC-Constraint". It states that, in the underlying structure, the quantifier cannot appear inside another, differently indexed Noun Phrase.[35] This is a stronger version of his previously stated "C-Constraint", and he proposes that while Mandarin must always follow the CC-Constraint, English can at times relax this constraint to follow the C-Constraint instead. This, he claims, leads to the difference in interpretation possibilities in the English and Mandarin versions of example (35), since the quantifier shei appears within the differently indexed Noun Phrase shei de muchin, and so it cannot be reindexed to have the same index as ta.[35]

Empty and overt pronoun interpretations

Sentences such as (36), below, also seem to have different interpretation possibilities from English at first:

(36)

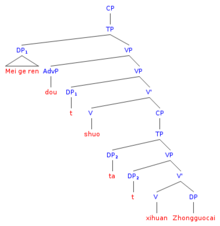

(a) Mei ge ren dou shuo ø xihuan Zhongguocai.

every CL person all say like Chinese food

'Everybody1 says that (I/you/he1/2/we/they...) like/likes Chinese cuisine.'

(b) Mei ge ren dou shuo ta xihuan Zhongguocai.

every CL person all say 3SG like Chinese food

'Eveybody1 says that he2 likes Chinese cuisine.'

(Y. Huang, 1994: 173(6.51))

Simplified syntax tree adapted from Y. Huang (1994) example 6.51a, made with phpSyntaxTree |

Simplified syntax tree adapted from Y. Huang (1994) example 6.51b, made with phpSyntaxTree |

In (36a), the empty pronoun ø is able to refer to any entity.[37] However, the preferred reading is for it to be interpreted as a variable bound to the quantifier mei ge ren (or everyone).[37] In contrast, the ta (he) in sentence (36b) is unable to have a bound variable interpretation, and must be interpreted as referring to some other third party.[37] Huang states that this is because the empty pronoun construction (36a) is possible, and so it is preferred as the construction that carries the bound variable interpretation.[37] This explanation is made as an extension of a claim put forward by Chomsky in his theory of anaphora, which states that where empty pronouns and overt pronouns are both able to be used as a reference, languages will prefer to use the empty pronoun.[38][39] This implies that, since English does not have an empty pronoun available in the above examples, the overt pronoun he is used to refer to the quantifier everybody.[37] However, since the empty pronoun is available in Mandarin, using it is preferred when the pronoun in the sentence is meant to corefer with everybody, as in (36a).[37][38][39]

German

Embedded possessives

Kratzer provides a German example:[29]

(37) 1st person singular *Ich bin der einzige, der t meinen Sohn versorg-t. 1SG be.1SG the.MASC.SG only.one who.MASC.SG 1SG.POSS.ACC son take.care.of-3SG I am the only one who is taking care of my son. (Kratzer, 2009: 191 (5))

(38) 1st person plural Wir sind die einzigen, die t unseren Sohn versorg-en. 1PL be.1/3PL the.PL only.ones who.PL 1PL.POSS.ACC son take.care.of-1/3PL We are the only ones who are taking care of our son. (Kratzer, 2009: 191 (7))

In the above examples, Kratzer notes that although examples (37) and (38) are grammatical, there is an underlying issue with (37). (37) is deemed to be not preferred due to how the bound variable readings in German for any embedded possessives is not allowed. Kratzer mentions that due to the grammaticality of German, there is a "person feature clash between possessive and embedded verbs" in (38). In order for (37) to have proper bound variable interpretation, proper 1st person verbal agreement must be addressed in the relative clause.[29]

Possessor-raising

Should a bound variable cause ungrammaticality, like in (37), then a possessor-raising construction is required.

(39) Wir sind die einzigen, denen du t unsere Röntgenbilder gezeigt hast. 1PL be.1/3PL the.PL only.ones who.PL.DAT 1PL.POSS.ACC X-rays shown have.SG We are the only ones who you showed our X-rays. (Kratzer, 2009: 200 (24))

(40) *Wir sind die einzigen, denen du t unsere Katze gefüttert hast. 1PL be.1/3PL the.PL only.ones who.PL.DAT 1PL.POSS.ACC cat fed have.SG We are the only ones for whom you fed our cat. (Kratzer, 2009: 200 (25))

(40), an example of possessor raising, is used when the absence of a bound variable causes ungrammaticality. In this instance, a separate head would pop up between the VP and v, preventing the v from binding to a bound variable interpretation.[29]

Multiple arguments against this, by Pylkkänen and by Hole, state otherwise. Pylkkänen's argument, about low applicatives and high applicatives, states that on a syntax tree level, low applicatives have an applicative morpheme below the verb in a sentence and involve an additional v, or pronoun maker.[40] In looking at the German examples, (40) is deemed ungrammatical due to the possessor-raising and misplacement of the pronoun maker, or lack of a bound variable interpretation. To Pylkkänen, (39) is considered a low applicative sentence, and grammatical.[29]

Hole's argument agrees with Pylkkänen's, stating that the dative argument would introduce a new head in between a VP and v, agreeing with Pylkkänen's low applicative theory.[29][41]

See also

- Free variables and Bound variables

- Antecedent (grammar)

- Anaphora (linguistics)

- Quantifier (linguistics)

- Pronoun

- Sloppy identity

Notes

- ↑ Hendrick (2005): 103

- 1 2 Chomsky (1980): 1–46

- ↑ Sportiche, Koopman, & Stabler (2014): 176, 319

- ↑ Carminati (2002): 1–34

- ↑ Sportiche, Koopman, & Stabler (2014): 161

- ↑ Carminati (2002): 2

- ↑ Sportiche, Koopman, & Stabler (2014): 168

- ↑ Sportiche, Koopman, & Stabler (2014): 170-172

- ↑ Sportiche, Koopman, & Stabler (2014): 176

- 1 2 Higginbotham (1980): 679–708

- ↑ Higginbotham (1980): 681–682

- 1 2 Higginbotham (1980): 682

- ↑ Chomsky (1980): 40

- ↑ Higginbotham (1980): 682–683

- 1 2 3 Higginbotham (1980): 685

- ↑ Higginbotham (1980): 689

- 1 2 3 4 Higginbotham (1980): 693

- 1 2 3 Higginbotham (1980): 686

- 1 2 Reinhart (1983): 60

- ↑ Reinhart (1983): 47

- ↑ Reinhart (1984): 150

- ↑ Reinhart (1983): 80

- ↑ Reinhart (1984): 157

- ↑ Reinhart (1984): 170

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reinhart (1984): 171

- ↑ Reinhart (1983) 50

- ↑ Chomsky (1993): 188

- 1 2 3 Reinhart (1984): 159

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Kratzer (2009)

- 1 2 3 Reinhart (1983): 55

- ↑ Reinhart (1983): 56

- 1 2 Reinhart (1983): 57

- ↑ Reinhart (1983): 82

- ↑ Higginbotham (1980): 695

- 1 2 3 4 Higginbotham (1980): 696

- 1 2 3 4 Huang, C. (1982): 409

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Huang, Y. (1994): 172–173

- 1 2 Chomsky (1982): 25

- 1 2 Chomsky (1993): 65

- ↑ Pylkkänen (2002): 19

- ↑ Hole (2005)

Bibliography

- Carminati, M. N. (1 February 2002). "Bound Variables and C-Command". Journal of Semantics 19 (1): 1–34. doi:10.1093/jos/19.1.1.

- Chomsky, Noam (1980). "On Binding". Linguistic Inquiry 11 (1): 1–46. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- Chomsky, Noam (1982). Some concepts and consequences of the theory of government and binding (6. printing ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT P. p. 25. ISBN 026203090X.

- Chomsky, Noam (1993). Lectures on government and binding : the Pisa lectures (7th ed. ed.). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. p. 65. ISBN 3110141310.

- Hendrick, Randall (2005). "Resumptive and bound variable pronouns in Tongan", pages 103–115 in Heinz & Ntelitheos (eds.) UCLA Working Papers in Linguistics 12 [Proceedings of AFLA XII].

- Higginbotham, James (1980). "Pronouns and Bound Variables". Linguistic Inquiry 11 (4): 679–708. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- Hole, Daniel (2005). "Reconciling “possessor” datives and “beneficiary” datives – Towards a unified voice account of dative binding in German", pages 213–241 in Maienborn & Wöllstein-Leisten (eds.) Event Arguments: Foundations and applications.

- Huang, C.-T. James (1995). "Logical form". Pages 125–240 in Gert Webelhuth (ed.). Government and binding theory and the minimalist program: principles and parameters in syntactic theory. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-18061-3

- Huang, Chung-Teh James (1982). "Logical Relations In Chinese and the Theory of Grammar". (Doctoral dissertation) (Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

- Huang, Yan (1994). The syntax and pragmatics of anaphora : a study with special reference to Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 172–173. ISBN 0521418879.

- Kratzer, Angelika (2009). "Making a Pronoun: Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Pronouns". Linguistic Inquiry 40 (2): 187–237. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Pylkkänen, Liina (2002). Introducing Arguments. (Doctoral dissertation) (Massachusetts Institute of Technology).

- Reinhart, Tanya (Feb 1983). "Coreference and Bound Anaphora: A Restatement of the Anaphora Questions". Linguistics and Philosophy 6 (1): 47–88. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Reinhart, T. (1984). Anaphora and semantic interpretation. (Repr. with corrections and rev. ed.). London u.a.: Croom Helm. ISBN 070992237X.

- Sportiche, Dominique; Koopman, Hilda; Stabler, Edward (2014). An Introduction to Syntactic Analysis and Theory (1. publ. ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0017-5.