Biguanide

| |

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| 56-03-1 | |

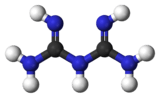

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image Interactive image |

| 507183 | |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:3095 |

| ChemSpider | 5726 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.229 |

| EC Number | 200-251-8 |

| 240093 | |

| KEGG | C07672 |

| PubChem | 5939 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C2H7N5 | |

| Molar mass | 101.11 g·mol−1 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.07, 13.25 |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

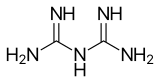

Biguanide (/baɪˈɡwɒnaɪd/) is the organic compound with the formula HN(C(NH)NH2)2. It is a colorless solid that dissolves in water to give highly basic solution. These solutions slowly hydrolyse to ammonia and urea.[1]

Biguanidine drugs

A variety of derivatives of biguanide are used as pharmaceutical drugs.

Antihyperglycemic agents

The term "biguanidine" often refers specifically to a class of drugs that function as oral antihyperglycemic drugs used for diabetes mellitus or prediabetes treatment.[2]

Examples include:

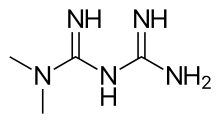

- Metformin - widely used in treatment of diabetes mellitus type 2

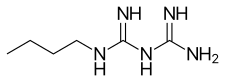

- Phenformin - withdrawn from the market in most countries due to toxic effects

- Buformin - withdrawn from the market due to toxic effects

- bioactive biguanidines

Metformin, an "unsym"-dimethylbiguanidine

Metformin, an "unsym"-dimethylbiguanidine

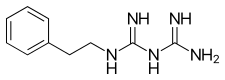

Phenformin. A phenethylated biguanidine.

Phenformin. A phenethylated biguanidine.

History

Galega officinalis (French lilac) was used in diabetes treatment for centuries.[3] In the 1920s, guanidine compounds were discovered in Galega extracts. Animal studies showed that these compounds lowered blood glucose levels. Some less toxic derivatives, synthalin A and synthalin B, were used for diabetes treatment, but after the discovery of insulin, their use declined. Biguanides were reintroduced into Type 2 diabetes treatment in the late 1950s. Initially phenformin was widely used, but its potential for sometimes fatal lactic acidosis resulted in its withdrawal from most pharmacopeias (in the U.S. in 1978).[4] Metformin has a much better safety profile, and it is the principal biguanide drug used in pharmacotherapy worldwide.

Mechanistic aspects

Biguanides do not affect the output of insulin, unlike other hypoglycemic agents such as sulfonylureas and meglitinides. Therefore, they are effective in Type 2 diabetics; and in Type 1 diabetes when used in conjunction with insulin therapy.

The mechanism of action of biguanides is not fully understood, and many mechanisms have been proposed for metformin.

Mainly used in Type II diabetes, metformin is considered to increase insulin sensitivity in vivo, resulting in reduced plasma glucose concentrations, increased glucose uptake, and decreased gluconeogenesis.

However, in hyperinsulinemia, biguanides can lower fasting levels of insulin in plasma. Their therapeutic uses derive from their tendency to reduce gluconeogenesis in the liver, and, as a result, reduce the level of glucose in the blood. Biguanides also tend to make the cells of the body more willing to absorb glucose already present in the blood stream, and there again reducing the level of glucose in the plasma.

Side effects and toxicity

The most common side effect is diarrhea and dyspepsia, occurring in up to 30% of patients. The most important and serious side effect is lactic acidosis, therefore metformin is contraindicated in renal insufficiency. Renal functions should be assessed before starting metformin. Phenformin and buformin are more prone to cause acidosis than metformin; therefore they have been practically replaced by it. However, when metformin is combined with other drugs (combination therapy), hypoglycemia and other side effects are possible.

Antimalarial

Some biguanides are also used as antimalarial drugs. Examples include:

Disinfectants

The disinfectants chlorhexidine, polyaminopropyl biguanide (PAPB), polihexanide, and alexidine feature biguanide functional groups.

References

- ↑ Thomas Güthner, Bernd Mertschenk and Bernd Schulz "Guanidine and Derivatives" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2006, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_545.pub2

- ↑ Rang; et al. (2003). Pharmacology (5th ed.). p. 388.

- ↑ Witters L. The blooming of the French lilac. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(8):1105–7. doi:10.1172/JCI14178. PMID 11602616. PMC 209536.

- ↑ Tonascia, Susan; Meinert, Curtis L. (1986). Clinical trials: design, conduct, and analysis. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. pp. 53–54, 59. ISBN 0-19-503568-2.