Yūrei

| Part of the series on |

| Japanese mythology and folklore |

|---|

|

| Mythic texts and folktales |

| Divinities |

| Legendary creatures and spirits |

| Legendary figures |

| Mythical and sacred locations |

| Sacred objects |

| Shintō and Buddhism |

| Folklorists |

Yūrei (幽霊) are figures in Japanese folklore, analogous to Western legends of ghosts. The name consists of two kanji, 幽 (yū), meaning "faint" or "dim" and 霊 (rei), meaning "soul" or "spirit." Alternative names include 亡霊 (Bōrei), meaning ruined or departed spirit, 死霊 (Shiryō) meaning dead spirit, or the more encompassing 妖怪 (Yōkai) or お化け (Obake).

Like their Chinese and Western counterparts, they are thought to be spirits kept from a peaceful afterlife.

Japanese afterlife

According to traditional Japanese beliefs, all humans have a spirit or soul called a 霊魂 (reikon). When a person dies, the reikon leaves the body and enters a form of purgatory, where it waits for the proper funeral and post-funeral rites to be performed, so that it may join its ancestors.[1] If this is done correctly, the reikon is believed to be a protector of the living family and to return yearly in August during the Obon Festival to receive thanks.[2]

However, if the person dies in a sudden or violent manner such as murder or suicide, if the proper rites have not been performed, or if they are influenced by powerful emotions such as a desire for revenge, love, jealousy, hatred or sorrow, the reikon is thought to transform into a yūrei, which can then bridge the gap back to the physical world. The emotion or thought need not be particularly strong or driving, and even innocuous thoughts can cause a death to become disturbed. Once a thought enters the mind of a dying person, their Yūrei will come back to complete the action last thought of before returning to the cycle of reincarnation.[3]

The yūrei then exists on Earth until it can be laid to rest, either by performing the missing rituals, or resolving the emotional conflict that still ties it to the physical plane. If the rituals are not completed or the conflict left unresolved, the yūrei will persist in its haunting.[4]

Oftentimes the lower the social rank of the person who died violently, or who was treated harshly during life, the more powerful as a yūrei they would return. This is illustrated in the fate of Oiwa in the story Yotsuya Kaidan, or the servant Okiku in Banchō Sarayashiki.

Appearance

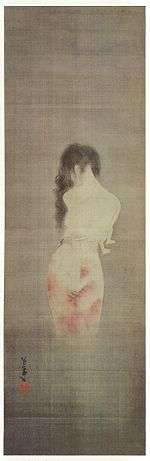

In the late 17th century, a game called Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai became popular,[5] and kaidan increasingly became a subject for theater, literature and other arts.[6] Ukiyo-e artist Maruyama Ōkyo created the first known example of the now-traditional yūrei, in his painting The Ghost of Oyuki.[7] The Zenshō-an in Tokyo houses the largest single collection of yūrei paintings which are only shown in August, the traditional month of the spirits.[8]

Today, the appearance of yūrei is somewhat uniform, instantly signalling the ghostly nature of the figure, and assuring that it is culturally authentic.

- White clothing: Yūrei are usually dressed in white, signifying the white burial kimono used in Edo period funeral rituals. In Shinto, white is a color of ritual purity, traditionally reserved for priests and the dead.[9] This kimono can either be a katabira (a plain, white, unlined kimono) or a kyokatabira (a white katabira inscribed with Buddhist sutras). They sometimes have a hitaikakushi (lit., "forehead cover"), which is a small white triangular piece of cloth tied around the head.[10]

- Black hair: The hair of a yūrei is often long, black and disheveled, which some believe to be a trademark carried over from kabuki theater, where wigs are used for all actors.[11] This is a misconception: Japanese women traditionally grew their hair long and wore it pinned up, and it was let down for the funeral and burial.

- Hands and feet: A yūrei's hands dangle lifelessly from the wrists, which are held outstretched with the elbows near the body. They typically lack legs and feet, floating in the air. These features originated in Edo period ukiyo-e prints, and were quickly copied over to kabuki.[12] In kabuki, this lack of legs and feet is often represented by using a very long kimono or even hoisting the actor into the air by a series of ropes and pulleys.[13]

- Hitodama: Yūrei are frequently depicted as being accompanied by a pair of floating flames or will o' the wisps (hitodama in Japanese) in eerie colors such as blue, green, or purple. These ghostly flames are separate parts of the ghost rather than independent spirits.[14]

Classifications

Yūrei

While all Japanese ghosts are called yūrei, within that category there are several specific types of phantom, classified mainly by the manner they died or their reason for returning to Earth.

- Onryō: Vengeful ghosts who come back from purgatory for a wrong done to them during their lifetime[14]

- Ubume: A mother ghost who died in childbirth, or died leaving young children behind. This yūrei returns to care for her children, often bringing them sweets[15]

- Goryō: Vengeful ghosts of the aristocratic class, especially those who were martyred[16]

- Funayūrei: The ghosts of those who died at sea. These ghosts are sometimes depicted as scaly fish-like humanoids and some may even have a form similar to that of a mermaid or merman[16]

- Zashiki-warashi: The ghosts of children, often mischievous rather than dangerous[17]

- Earth-bound spirits (Japanese: 地縛霊, hepburn: jibakurei): Something of a rarity among Yūrei, these spirits do not seek to fulfill an exact purpose and are instead bound to a specific location or situation.[18] Famous examples of this include the famous story of Okiku and the haunting in Ju-On: The Grudge.[19]

Buddhist ghosts

There are two types of ghosts specific to Buddhism, both being examples of unfulfilled earthly hungers being carried on after death. They are different from other classifications of yūrei due to their wholly religious nature.

Ikiryō

In Japanese folklore, not only the dead are able to manifest their reikon for a haunting. Living creatures possessed by extraordinary jealousy or rage can release their spirit as an ikiryō 生き霊, a living ghost that can enact its will while still alive.[16]

The most famous example of an ikiryo is Rokujō no Miyasundokoro, from the novel The Tale of Genji. A mistress of the titular Genji who falls deeply in love with him, the lady Rokujō is an ambitious woman whose ambition is denied upon the death of her husband. The jealousy she repressed over Genji transformed her slowly into a demon, and then took shape as an Ikiryō upon discovering that Genji's wife was pregnant. This Ikiryō possessed Genji's wife, ultimately leading to her demise. Upon realising that her jealousy had caused this misfortune, she locked herself away and became a nun until her death, after which time her spirit continued to haunt Genji until her daughter performed the correct spiritual rites.[21][22]

Hauntings

Yūrei often fall under the general umbrella term of obake, derived from the verb bakeru, meaning "to change"; thus obake are preternatural beings who have undergone some sort of change, from the natural realm to the supernatural.

However, Yūrei differ from traditional bakemono due to their temporal specificity. The Yūrei is one of the only creatures in Japanese mythology to have a preferred haunting time (the hour of the bull, around 2:00-2:30am, the witching hour for Japan, when the veils between the world of the dead and the world of the living are at their thinnest). By comparison, normal obake could strike at any time, often darkening or changing their surroundings should they feel the need.[23] Similarly, Yūrei are more bound to specific locations of haunting than the average bakemono, which are free to haunt any place without being bound to it.[24]

Yanagita Kunio generally distinguishes Yūrei from Obake by noting that Yūrei tend to have a specific purpose for their haunting, such as vengeance or completing unfinished business.[25] While for many Yūrei this business is concluded, some Yūrei such as the famed Okiku remain earthbound due to the fact that their business is not possible to complete. In Okiku's case, this business is counting plates hoping to find a full set, but the last plate is invariably missing or broken according to the different retellings of the story. This means that her spirit can never find peace, and thus will remain a jibakurei.[26]

Famous hauntings

Some famous locations that are said to be haunted by yūrei are the well of Himeji Castle, haunted by the ghost of Okiku, and Aokigahara, the forest at the bottom of Mt. Fuji, which is a popular location for suicide. A particularly powerful onryō, Oiwa, is said to be able to bring vengeance on any actress portraying her part in a theater or film adaptation.

Okiku, Oiwa, and the lovesick Otsuya together make up the San O-Yūrei (Japanese: 三大幽霊, lit "three great Yūrei") of Japanese culture. These are Yūrei whose stories have been passed down and retold throughout the centuries, and whose characteristics along with their circumstances and fates have formed a large part of Japanese art and society.[27]

Exorcism

The easiest way to exorcise a yūrei is to help it fulfill its purpose. When the reason for the strong emotion binding the spirit to Earth is gone, the yūrei is satisfied and can move on. Traditionally, this is accomplished by family members enacting revenge upon the yūrei's slayer, or when the ghost consummates its passion/love with its intended lover, or when its remains are discovered and given a proper burial with all rites performed.

The emotions of the onryō are particularly strong, and they are the least likely to be pacified by these methods.

On occasion, Buddhist priests and mountain ascetics were hired to perform services on those whose unusual or unfortunate deaths could result in their transition into a vengeful ghost, a practice similar to exorcism. Sometimes these ghosts would be deified in order to placate their spirits.

Like many monsters of Japanese folklore, malicious yūrei are repelled by ofuda (御札), holy Shinto writings containing the name of a kami. The ofuda must generally be placed on the yūrei's forehead to banish the spirit, although they can be attached to a house's entry ways to prevent the yūrei from entering.

See also

- Bancho Sarayashiki

- Botan Doro

- Hungry ghost

- Inoue Enryo

- Japanese mythology

- Japanese Urban Legends

- J-Horror

- Kaidan

- Kayako Saeki

- Sadako Yamamura

- Sayako

- Shinigami

- Yokai

- Yotsuya Kaidan

- Yūrei zaka

Notes

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 81-85.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 139-140.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 81.

- ↑ Foster 2009, p. 149.

- ↑ Foster 2009, p. 53.

- ↑ Balmain 2008, p. 16-17.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 27-30.

- ↑ Zensho-an.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 44.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 45-46.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 48.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 49.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 49-50.

- 1 2 Davisson 2014, p. 215.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 216.

- 1 2 3 4 Davisson 2014, p. 214.

- ↑ Blacker 1963, p. 87.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 129.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, pp. 129-130.

- ↑ Hearn 2006, p. 43-47.

- ↑ Meyer 2014, p. Rokujō no Miyasundokoro.

- ↑ Murasaki 2010, p. 679-693.

- ↑ Foster 2014, p. 23.

- ↑ Reider 2010, p. 162.

- ↑ Yanagita 1970, pp. 292-293.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 111-112.

- ↑ Davisson 2014, p. 87.

References

- Balmain, Collette (2008). Introduction to Japanese Horror Film. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2475-1.

- Blacker, Carmen (1963). "The Divine Boy in Japanese Buddhism". Asian Folklore Studies. 22: 77–88. JSTOR 1177563.

- Davisson, Zack (2014). Yūrei The Japanese Ghost. Chin Music Press. ISBN 978-09887693-4-2.

- Davisson, Zack. "Yūrei Stories". hyakumonogatari.com. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- Foster, Michael Dylan (2009). Pandemonium and Parade Japanese Demonology and the Culture of Yōkai. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520253629.

- Foster, Michael Dylan (2014). The Book of Yōkai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. Shinonome Kijin. Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27102-9.

- Hearn, Lafcadio (2006). Kwaidan. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-45094-5.

- Iwasaka, Michiko; Toelken, Barre (1994). Ghosts And The Japanese: Cultural Experience in Japanese Death Legends. Utah: Utah State University Press. ISBN 0874211794.

- Meyer, Matthew (2014). "Rokujō no Miyasundokoro". yokai.com. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Murasaki, Shikibu (2001). The Tale of Genji. Translated by Royall Tyler. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-243714-8.

- Reider, Noriko T. (2010). Japanese Demon Lore: Oni from Ancient Times to the Present. Utah State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87421-793-3.

- Yanigata, Kunio (1970). 定本柳田國男集. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō.

- Zensho-an. "Yurei Goaisatsu". Retrieved 16 May 2016.