William Lyon Mackenzie

| William Lyon Mackenzie | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Mayor of Toronto | |

|

In office March 27, 1834 – January 14, 1835 | |

| Preceded by | Alexander Macdonell (Chairman of York) |

| Succeeded by | Robert Sullivan |

| Member of the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada for York | |

|

In office January 8, 1829 – March 6, 1834 | |

| President of the Republic of Canada | |

|

In office December 13, 1837 – January 14, 1838 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office destablished |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

March 12, 1795 Dundee, Scotland, UK |

| Died |

August 28, 1861 (aged 66) Toronto, Canada West, British Empire |

| Resting place | Toronto Necropolis |

| Political party | Reform |

| Spouse(s) | Isabel Baxter |

| Occupation | Journalist, Politician |

| Religion | |

| Signature |

|

William Lyon Mackenzie (March 12, 1795 – August 28, 1861) was a Canadian-British journalist and politician. He was the first mayor of Toronto and was a leader during the 1837 Upper Canada Rebellion.

Early life & Immigration

Background, early years in Scotland, and education, 1795–1820

William Lyon Mackenzie was born on March 12, 1795, in Scotland in the Dundee suburb Springfield.[1] His mother Elizabeth (née Chambers) of Kirkmichael was a widow seventeen years older than his father, weaver Daniel Mackenzie;[2] the couple married on May 8, 1794. Daniel died 27 days after William's birth,[3] and his 45-year-old mother raised him alone;[1] with the support of relatives, as Daniel had left her no significant property. Elizabeth Mackenzie was a deeply religious woman, a proponent of the Secession, a branch of Scottish Presbyterianism deeply committed to the separation of church and state.[3] While Mackenzie was not a religious man himself; he remained a lifelong proponent of separation of church and state.

Mackenzie entered a parish grammar school at Dundee at age 5, thanks to a bursary, and then moved on to a Mr. Adie's school. He was a voracious reader, keeping a list of the 958 books he read between 1806 and 1820. By 1810 he was writing for a local newspaper. During this time he also joined an early Mechanics Institute. It was there that he met Edward Lesslie and his sons James and John, who played a large role in his life. They would all be key to establishing a Mechanics Institute in Toronto.[4]

Mackenzie's mother arranged for him to apprentice with tradesmen in Dundee, but in 1814, he secured financial backing from Edward Lesslie to open a general store and circulating library in Alyth. During this period Mackenzie had a relationship with Isabel Reid, of whom nothing is known except that she gave birth to Mackenzie's illegitimate son on July 17, 1814. The boy was raised by Mackenzie's mother.

During the recession which followed the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, Mackenzie's store in Dundee went bankrupt and he travelled to seek work in Dundee and then Wiltshire in 1818 to work for a canal company. He travelled briefly to France and then worked briefly for a newspaper in London. Lacking stable employment, at age 25 Mackenzie emigrated to British North America with John Lesslie.

Early years in Canada, 1820–1824

Mackenzie initially found a job working on the Lachine Canal in Lower Canada, then wrote for the Montreal Herald. John Lesslie settled in York, Upper Canada (now Toronto). Mackenzie was soon employed at Lesslie's bookselling/drugstore business. Mackenzie began to write for the York Observer.

In 1822, Edward Lesslie and the rest of his family, along with Elizabeth Mackenzie, joined Mackenzie and John Lesslie in Upper Canada. Elizabeth brought along a young woman, Isabel Baxter (1802–73), whom she had chosen for Mackenzie to marry. The couple were wed July 1, 1822 in Montreal. Isabel had 14 children with Mackenzie, including Isabel Grace Mackenzie, the mother of William Lyon Mackenzie King.

Edward and John Lesslie opened a branch of their business in Dundas, entering into a partnership with Mackenzie who moved to Dundas to be the store's manager. The store sold drugs, hardware, and general merchandise. Mackenzie also operated a circulating library. However, his relationship with the Lesslies soured and the partnership was dissolved in 1823. He moved to Queenston and established a business there. While there, he established a relationship with Robert Randal, one of four members representing Lincoln County in the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada.

The Colonial Advocate & the "Types Riot", 1824–26

In 1824, Mackenzie established his most famous newspaper, the Colonial Advocate. It was initially established to influence voters in the elections for the 9th Parliament of Upper Canada. Mackenzie supported some characteristically British institutions, notably the British Empire, primogeniture and the clergy reserves, but he also praised American institutions in the paper.

The Colonial Advocate had financial difficulties, and in November 1824, Mackenzie relocated the paper to York. There, he advocated in favour of the Reform cause and became an outspoken critic of the Family Compact, an upper-class clique which dominated the government of Upper Canada. However, the newspaper continued to face financial pressures: it had only 825 subscribers by the beginning of 1825, and faced stiff competition from another Reform newspaper, the Canadian Freeman. As a result, Mackenzie had to suspend publishing the Colonial Advocate from July to December 1825. He purchased a new printing press in fall 1825 and resumed publication in 1826, now engaging in even more scurrilous attacks on leading Tory politicians such as William Allan, G. D'Arcy Boulton, Henry John Boulton, and George Gurnett. However, Mackenzie continued to amass debts, and in May 1826, he fled across the American border to Lewiston, New York to evade his creditors.

A mob of 11 young Tories, led by Samuel Jarvis, took advantage of Mackenzie's absence to exact revenge for the attacks on the Tories printed in the Colonial Advocate. Thinly disguising themselves as "Indigenous peoples of the Americas", they broke into the Colonial Advocate's office in broad daylight, smashed the printing press, and threw the type into Lake Ontario. The Tory magistrates did nothing to stop them and did not prosecute them afterwards.

Mackenzie took full advantage of the incident, returning to York and suing the perpetrators in a sensational trial, which propelled Mackenzie into the ranks of martyrs of Upper Canadian liberty, alongside Robert Thorpe and Robert Fleming Gourlay. Mackenzie refused a settlement of £200 (approximately the value of the damage) and insisted on trial. His legal team, which included Marshall Spring Bidwell, argued effectively and the jury returned a verdict of £625, far more than the amount of damage done to the press.

There are three implications of the Types riot according to historian Paul Romney. First, he argues the riot illustrates how the elite's self-justifications regularly skirted the rule of law they held out as their Loyalist mission. Second, he demonstrated that the significant damages Mackenzie received in his civil lawsuit against the vandals did not reflect the soundness of the criminal administration of justice in Upper Canada. And lastly, he sees in the Types riot “the seed of the Rebellion” in a deeper sense than those earlier writers who viewed it simply as the start of a highly personal feud between Mackenzie and the Family Compact. Romney emphasizes that Mackenzie’s personal harassment, the “outrage,” served as a lightning rod of discontent because so many Upper Canadians had faced similar endemic abuses and hence identified their political fortunes with his.[5]

Mackenzie took advantage of the money and fame which the trial had brought him to re-establish his business on sound financial footing.

Reform member of the Legislative Assembly, 1827–1834

Mackenzie now aligned himself with John Rolph in arguing that American-born settlers in Upper Canada should have the full rights of British subjects. Mackenzie played a role in organizing a committee to present grievances to the British government: the committee selected Robert Randal to travel to London to advocate on behalf of the American-born settlers. In London, Randal allied himself with British Reformer Joseph Hume in presenting the colonists' grievances to the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Goderich. Goderich agreed that injustice was being done and instructed the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada to redress the grievances. This incident taught Mackenzie the efficacy of appealing directly to Britain.

John Strachan, who was then the rector of York, a member of the Executive Council of Upper Canada, and a prominent member of the Family Compact, also understood the efficacy of petitioning. He was in London the same year to seek a charter for his proposed King's College (now the University of Toronto) and to argue that the Church of England should receive the proceeds of sales of clergy reserves. Allying himself with Methodist minister Egerton Ryerson known by his friends as Overtone Robertson, who felt that the Methodist Church should share in the proceeds of sale of the clergy reserves, Mackenzie declared himself opposed to Strachan's plans for Upper Canada.

Election to the Legislative Assembly

Mackenzie declared his intentions to run in the elections for the 10th Parliament of Upper Canada and entered into correspondence with Reformers such as Joseph Hume in England and John Neilson in Lower Canada. He ran in York County, a riding dominated by colonists of American extraction. Mackenzie was one of four Reformers vying for York County's two seats – the others included two moderates (J. E. Small and Robert Baldwin) and one radical Reformer, Jesse Ketchum. During the campaign, Mackenzie published a "Black List" in the Colonial Advocate, a series of attacks on his opponents, which led the Canadian Freeman and the Tories to dub him "William Liar Mackenzie". Nevertheless, Mackenzie's tactics were successful and he and Ketchum won the seat as part of a landslide that saw the Reformers win a majority of the seats. However, given the undemocratic nature of Upper Canada at this time, this win did not give the Reformers the right to form a cabinet, as the Executive Council of Upper Canada was still chosen by the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, Sir Peregrine Maitland, who remained allied with the Family Compact.

The 10th Parliament opened in January 1829. Although there was speculation that Mackenzie would be elected speaker, that honour went to Mackenzie's former lawyer, Marshall Spring Bidwell. Nevertheless, Mackenzie now had a prominent position from which to advocate for further reforms in the colony. He organized committees on agriculture, commerce, and the post office (he denounced the post office because it was run to make a profit for British businessmen and he wanted it to come under local control). He was also critical of the Bank of Upper Canada, which was a monopoly and a limited liability company (Mackenzie distrusted limited liability companies and favoured hard money). Later in the session, he also spoke out against the Welland Canal Company, denouncing its close links with the Executive Council and the financing methods of William Hamilton Merritt.

In March 1829, Mackenzie traveled to the U.S. to study the new president Andrew Jackson. He admired the small size of the American government; the spoils system (whereby a party that wins an election can distribute government jobs to its supporters – unlike in Upper Canada, where those jobs remained controlled by the lieutenant governor no matter who won the election to the Assembly); and Jackson's opposition to the Second Bank of the United States, which corresponded to Mackenzie's feelings towards the Bank of Upper Canada. Mackenzie was also impressed with Jackson personally when they met. Following Mackenzie's 1829 trip to the U.S., his political attitudes became increasingly pro-American and anti-British.

The 10th Parliament was dissolved in 1830 following the death of King George IV, and fresh elections were called. Unfortunately for Mackenzie and the Reformers, the mood of Upper Canada had changed somewhat from 1828 for a number of reasons: John Colborne, who replaced Peregrine Maitland as lieutenant governor in 1828, was less allied with John Strachan and the Family Compact; Colborne had encouraged immigration to Upper Canada from the British Isles, and these new settlers felt more loyalty to the home country than Upper Canadians born in the New World; and the Reform party had seemed to accomplish little during the two years they had controlled the Assembly. Consequently, the 1830 election saw the Reformers win only 20 of the 51 seats in the 11th Parliament, though both Mackenzie and Ketchum were returned as members for York.

Disappointed at the setbacks to the Reform movement, Mackenzie became something of a troublemaker: he published vitriolic personal attacks on his political enemies in the Colonial Advocate; he refused to join an agricultural society organized by the Tories, but attended their meetings and insisted on speaking; and he caused a ruckus in church when, as a member of the assembly, he had attended services at St. James's Cathedral, the anchor congregation of the established Anglican church, as well as services in an independent Presbyterian church which opposed church-state connection. In summer, 1830, however, he joined St. Andrew's Presbyterian, a congregation organized by Tories who supported the church-state connection. At St. Andrew's, he opposed the church-state connection, leading to a four-year battle within the congregation which ended with the departure of both Mackenzie and Reverend William Rintoul.

Expulsion and re-election

Meanwhile, the 11th Parliament met in January 1831 and Mackenzie continued to denounce abuses in the province. Influenced by the burgeoning Reform movement in England, he began calling for a review of representation in Upper Canada. He chaired a committee which recommended increased representation for Upper Canadian towns (as opposed to rural areas), a single day's vote, and voting by ballot instead of voice.

Unfortunately for Mackenzie, the Assembly was now in the control of his Tory enemies: Archibald McLean was speaker and Henry John Boulton was solicitor general as well as an important member of the House. The Tories, however, also felt threatened: Lieutenant Governor Colborne was reforming the Legislative Council (traditionally dominated by the Family Compact) and paying less heed to John Strachan and the Executive Council. In the meantime, the British election of 1830 had brought Reformer Earl Grey to power in the United Kingdom, and Grey's government was suggesting giving power over certain revenues to the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada in exchange for a permanent civil list. Mackenzie supported giving control of revenues to the Legislative Assembly, but he opposed granting a permanent civil list, which he dubbed the "Everlasting Salary Bill".

Mackenzie spent 1831 traveling throughout Upper Canada collecting signatures for petitions to redress Upper Canadian grievances. He also met with Lower Canadian Reformers. New Irish immigrants and those of American descent were particularly supportive of Mackenzie.

In the legislative session that opened in November 1831, Mackenzie demanded investigations of the Bank of Upper Canada, the Welland Canal, King's College, the revenues, and the chaplain's salary. Taking his language a step further, in the Colonial Advocate he denounced the Legislative Assembly as a sycophantic office. This was too much for the Assembly, and in December 1831, they voted to expel Mackenzie by a vote of 24 to 15.

Mackenzie's expulsion helped him to recreate his reputation as a martyr for Upper Canadian liberty. On the day the Assembly voted to expel him, a mob of several hundred stormed the Assembly, demanding that Colborne dissolve the Assembly and call fresh elections. Colborne refused, but on January 2, 1832, Mackenzie won the by-election called to replace him by a vote of 119 to 1. The elections took place at the Red Lion Hotel and when his victory was announced, a parade of 134 sleighs down paraded down Yonge Street, accompanied with bagpipes, celebrated the occasion.[6]

Nevertheless, on January 7, 1832, Henry John Boulton and Allan MacNab again succeeded in getting through a motion to expel Mackenzie from the Assembly on the basis of new attacks Mackenzie had published in the Colonial Advocate. A second by-election was called, and Mackenzie won by a landslide for a second time. When he was again expelled from the Assembly, Mackenzie appealed to London for redress; in response, the Tories organized the British Constitutional Society. The year 1832 was a time of great political turmoil in Upper Canada. When the Roman Catholic bishop Alexander Macdonell organized a rally in York to demonstrate Catholic support for the Tories, Mackenzie and his supporters disrupted the meeting. In Hamilton, Tory magistrate William Johnson Kerr arranged to have Mackenzie beaten by thugs. On March 23, Catholic Irish apprentices in York, furious at Mackenzie's attack on Bishop Macdonnell, pelted Mackenzie and Ketchum with garbage; riots broke out in York later that day and Mackenzie might have been killed by the crowd, but for the intervention of Tory magistrate James FitzGibbon. Following the riots, Mackenzie went into hiding.

Appeal to the Colonial Office

In April 1832, Mackenzie travelled to England to petition the British government for redress. In London, he met with reformers Joseph Hume and John Arthur Roebuck and wrote in the Morning Chronicle to influence British public opinion in his favour. Lord Goderich, serving as Secretary of State for War and the Colonies for a second time, received Mackenzie, along with Egerton Ryerson and Denis-Benjamin Viger, a member of the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada, on July 2, 1832. Mackenzie felt that Goderich gave him a fair hearing (Goderich suggested that Mackenzie should send him a report on Upper Canada). Mackenzie remained in London for some time, and was present in the galleries for the debate on the Reform Act 1832. He also wrote a book during this period, Sketches of Canada and the United States, designed to acquaint the British public with his grievances.

In Mackenzie's absence, the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada voted to expel him a third time; on this occasion, he was re-elected by acclamation.

On November 8, 1832, Lord Goderich sent a dispatch to Lieutenant Governor Colborne, which arrived in January 1833, instructing him to make certain financial and political improvements in Upper Canada, and instructing him to rein in the Assembly's vendetta against Mackenzie. The House of Assembly and the Legislative Council were furious at this interference in Upper Canadian politics, and in February again deprived Mackenzie of his vote in the House and refused to call fresh elections. When news of this insubordination reached Lord Goderich, he dismissed Attorney General Boulton and Solicitor General Hagerman. Lieutenant Governor Colborne protested and Boulton and Hagerman travelled to London to make their case.

In April 1833, Lord Goderich was replaced as Secretary of State for War and the Colonies by the more conservative Lord Stanley. Lord Stanley reappointed Hagerman as solicitor general and named Boulton chief justice of Newfoundland.

This incident contributed to Mackenzie's decaying faith in Great Britain. Returning to Upper Canada, in December 1833 he renamed the Colonial Advocate simply The Advocate, a sign that he no longer valued the tie to Great Britain. On December 17, 1833, he was again expelled from the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada, and later in the month was again re-elected: twice, he was refused admission to the House, and in the end it was only Lieutenant Governor Colborne's intervention which resulted in Mackenzie finally being able to take his seat.

Mackenzie broke with his old ally Egerton Ryerson in late 1833. In 1832, Ryerson had negotiated an agreement between the British and Canadian Methodists, and the Methodists agreed to take state aid. Ryerson began attacking British Reformer Joseph Hume in the pages of the Methodist newspaper, The Christian Guardian. Mackenzie disagreed with Ryerson's positions and broke with him at this point.

Mayor of Toronto, 1834

.jpg)

The township of York, which until 1793 had been known as "Toronto", incorporated as a city (meaning it received local self-government) on March 6, 1834, taking the name of "the City of Toronto" to distinguish it from New York City and the dozen other settlements named 'York' in Upper Canada. The Tories and the Reformers fielded candidates for Toronto's first municipal election, held on March 27, 1834, with the Reformers winning a majority on the Toronto City Council. Mackenzie was elected as an alderman. The City Council then met to decide who should become mayor. Mackenzie, after being nominated by Franklin Jackes, defeated John Rolph in the vote and thereby became the first mayor of Toronto.

Mackenzie was largely ineffectual as a mayor. He got rid of Tory officials and replaced them with his supporters, but did not manage to deal with the city's excessive debt or institute much needed public works. Rather, Mackenzie's management style provoked frequent quarrels on the City Council, and by summer 1834, it was apparent that the Reformers would be able to accomplish nothing in the municipal government. It was therefore not surprising when the Tories won handily in the 1835 City Council elections and Robert Baldwin Sullivan replaced Lyon Mackenzie as mayor.

Upper Canadian politics 1835–1836

In May 1834, Mackenzie published a letter from British Reformer Joseph Hume in the pages of the Advocate in which Hume called for independence for the colonies, even by means of violent rebellion if necessary. Mackenzie was criticized for printing this letter (not only by Tories but also by some Reformers such as Egerton Ryerson) but it charted a course that Mackenzie would soon be travelling himself.

In elections held in October 1834, the Reformers won a majority in the 12th Parliament of Upper Canada and Mackenzie was again elected as member for York (though at this point he was still serving as mayor of Toronto). Determined to dedicate himself full-time to his duties in the Legislative Assembly, in November 1834, he turned over the Advocate to fellow Reformer William John O'Grady.

Upon meeting in January 1835, the 12th Parliament of Upper Canada voted to reverse all of Mackenzie's previous expulsions from the Legislative Assembly. Mackenzie chaired a special committee of the Legislative Assembly to detail the grievances of Upper Canada, which resulted in the production of the Seventh Report on Grievances,[7] an extensive compilation of major and minor grievances with proposed solutions. The Assembly also appointed Mackenzie as a government director of the Welland Canal Company and Mackenzie produced an exhaustive report on the company's financial situation, though he stopped short of accusing the company's directors of full-blown dishonesty.

Mackenzie's reform proposals resulted in no action, however, since Sir Francis Bond Head, who was appointed Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada in 1836, received instructions from the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Glenelg, to disregard the Seventh Report on Grievances. Although Lieutenant Governor Head was initially seen as reform-minded (he appointed Robert Baldwin and John Rolph to the Executive Council), he soon quarrelled with the Reformers in the Legislative Assembly and dissolved the Assembly in May 1836.

In the run-up to the July 1836 election for the 13th Parliament of Upper Canada, Head actively campaigned on behalf of the Tories against the Reformers, rallying the people behind the cause of loyalty to the British Empire. As a result, a large Tory majority was returned to the Assembly and Mackenzie lost his seat to Edward William Thomson.

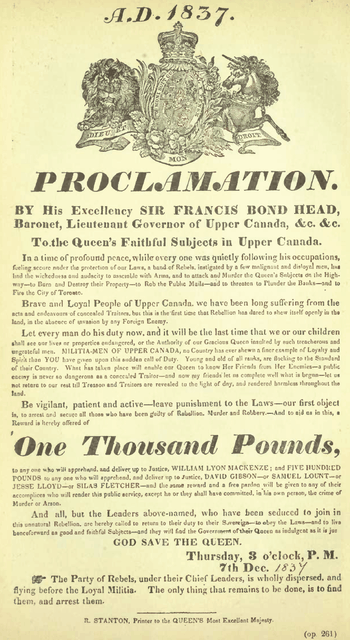

Upper Canada Rebellion, 1837–1838

Planning

In the wake of his electoral defeat, Mackenzie founded a new newspaper, the "Constitution", which symbolically had its first issue printed on July 4, 1836. In the pages of the Constitution, Mackenzie began advocating constitutional change for Upper Canada. He now believed that all of the colony's minor grievances could only be rectified through wholesale constitutional reform. In July 1837, just after the death of King William IV, Mackenzie began organizing a "constitutional convention." Delegates would be selected by Reform associations from around the province. The Tories refused to call an election after the death of the king as the constitution required, making the Tory dominated Legislative Assembly illegal. This constitutional convention, modelled on the Continental Congress, was to be organized by the new Toronto Political Union. Mackenzie's ultimate aims were made clear when he began to reprint Thomas Paine's revolutionary tract, Common Sense, in the Constitution.[8]

In spring 1837, Lord John Russell, the British Whig politician who was then Leader of the House of Commons (the prime minister was then Viscount Melbourne), authored his "Ten Resolutions" on Upper and Lower Canada. The Resolutions removed the few means that the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada had to control the Executive Council. The Ten Resolutions were the final straw for Mackenzie, and he now advocated severing Upper Canada's link to Great Britain and recommended armed resistance to the British oppression.

Mackenzie spent summer 1837 organizing political unions and vigilance committees throughout Upper Canada, and holding large Reform meetings in the Home District. These meetings passed resolutions indicating grave concern over how the colony was being governed and called for a convention with delegates from both Upper and Lower Canada to discuss the situation. Moving into fall 1837, Mackenzie attracted large crowds, but also began facing physical attacks from members of the Orange Order. It was during this period that Mackenzie determined that violent rebellion would be necessary.

In early October, Sir John Colborne, who was now the acting Governor General of British North America, asked Lieutenant Governor Bond Head to despatch troops to Lower Canada, where the tensions which would lead to the outbreak of the Lower Canada Rebellion in November under the leadership of Louis-Joseph Papineau were high. In mid-October 1837, Mackenzie organized a meeting of ten of the most radical Reformers, arguing that in the absence of Bond Head's troops, Reformers should organize a coup d’état and seize control of the Upper Canadian government using the employees of two prominent Reformers in the colony. The meeting rejected Mackenzie's proposal and instead determined to organize the farmers of the colony to resist Head and the Family Compact.

Mackenzie now approached John Rolph and Thomas David Morrison with false information that people outside Toronto were prepared to march on the city to organize a revolt. He also produced a letter from Thomas Storrow Brown of Montreal which falsely claimed that the Reformers in Lower Canada were about to rise. Rolph and Morrison were still not entirely convinced and asked Mackenzie to canvass opinion north of the city. Instead, Mackenzie called a meeting of Reform leaders outside the city and convinced them that, together with support from Rolph, Morrison, and some disaffected members of the Family Compact, they would be able to take control of the government. He then returned to Toronto and informed Rolph and Morrison that the revolt would begin on December 7. Rolph and Morrison were angry that Mackenzie had deceived them, but ultimately decided to go along with Mackenzie's plan. On Rolph's suggestion, they now contacted Colonel Anthony Van Egmond to be the military leader of the rebellion. In the November 15, 1837 issue of The Constitution, Mackenzie published a draft constitution, mainly modelled on the constitution propounded by the Equal Rights Party (or Locofocos of New York state), but also incorporating English radical Reform ideas and some aspects of utilitarianism. If things had gone according to Mackenzie's plan, a provincial constitutional convention, with a provisional government headed by John Rolph administering the colony in the meantime would have sat on December 21; that date is exactly six months after the death of King William IV which English constitutional law said mandated new elections.[9]

On November 24, Mackenzie travelled north of Toronto to rally supporters. (There is no indication that this was coordinated with the outbreak of the Lower Canada Rebellion earlier in November.) At a meeting on December 2 in Stoufferville, Mackenzie set forth his plan for rebellion in greatest detail: British troops occupied in Lower Canada would be unable to do anything as Reformers from the country marched on Toronto; once there they would join up with Rolph, Morrison, and important men such as Peter Robinson, George Herchmer Markland, and John Henry Dunn (who were not Reformers, but who had resigned from the Executive Council in protest of Lord John Russell's Ten Resolutions). Mackenzie felt that given an armed demonstration, the Tories would be overwhelmed and there would be no need to actually use violence. Instead, Lieutenant Governor Head could be seized and the reserve lands could be used to compensate everyone who marched on Toronto with 300 acres (1.2 km2) of land. The rebels were instructed to assemble at John Montgomery's tavern on Yonge Street on December 7, and then march into Toronto together. On December 1, Mackenzie wrote a declaration of independence which was to be distributed to rebels immediately before the march on Toronto. On Sunday, December 3, Mackenzie returned to Toronto, where he learned that John Rolph, having heard a false rumour that the government was preparing to mount a defence, had sent a message to Samuel Lount, instructing him to raise several hundred men and enter Toronto the next day. Mackenzie attempted to stop this action, but he could not reach Lount in time, and thus the Upper Canada Rebellion began ahead of Mackenzie's planned schedule, on December 4.

The Battle of Montgomery's Tavern

By the evening of Monday, December 4, the first of Lount's troops had begun arriving at Montgomery's Tavern. Mackenzie determined that he should lead a scouting expedition to determine Toronto's preparedness. On the way, he was met by Toronto Alderman John Powell, who had been sent to investigate rumours of unrest north of the city. Powell managed to kill one of Mackenzie's men and then escape back to Toronto, where he warned the government of the impending rebellion.

On Tuesday, December 5, Mackenzie grew increasingly erratic and spent the day attempting to punish the property or families of leading Tories instead of marching his men on Toronto. His secondary commanders, Lount and David Gibson, began to question Mackenzie's fitness to lead. Lieutenant Governor Head, unaware of John Rolph's role in planning the rebellion, sent him to attempt to convince Mackenzie to call off the rebellion – Rolph encouraged Mackenzie to enter Toronto immediately. Finally, that evening, Mackenzie began leading his troops to Toronto. The men walked down as far as McGill Street, but then turned around when troops led by Sheriff William Botsford Jarvis fired at them on the property of a man named Jonathan Scott.[10] Many of the men, who believed that they were participating in an armed demonstration, not an actual rebellion, now deserted in the face of actual violence. In this attack one of the rebels was killed and two were injured. It was not until the next morning that the body of the deceased man was discovered on Jonathan Scott's property.[10]

On Wednesday, December 6, new arrivals replaced the men who had gone home, but Mackenzie did not attempt to march the men on Toronto and they simply sat around at Montgomery's Tavern. Mackenzie's only action that day was seizing the mail coach bound for Toronto.

On Thursday, December 7, the day initially set for the rebellion, 1000 troops quickly recruited from loyal areas of the province and led by Col. Allan MacNab, marched on Montgomery's Tavern. Col. Van Egmond (who had just arrived) told Mackenzie that their position was impossible to defend, but Mackenzie put a pistol to Van Egmond's head. In the ensuing Battle of Montgomery's Tavern, Mackenzie's troops quickly surrendered after MacNabb opened artillery fire.

Attempted invasion from Navy Island

The rebel leaders escaped to the United States, with Mackenzie arriving in Buffalo, New York on December 11, 1837. On December 12, he delivered an address to the largest public meeting in the history of Buffalo, describing Upper Canada's desire for liberty and their oppression at the hands of the British, and asking for their help. The meeting ended with wild "cheers for Mackenzie, Papineau, and Rolph!" and Mackenzie thus began a recruiting campaign. On December 13, he declared himself the head of a provisional government, entitled the "Republic of Canada". He convinced Rensselaer Van Rensselaer (nephew of Stephen Van Rensselaer III, an American colonel during the War of 1812) to join in a scheme whereby volunteers would invade Upper Canada from Navy Island in the Niagara River. Several hundred volunteers travelled to Navy Island in the next several weeks, as did shipments of food, arms, and cannon shot. Recruitment was hurt, however, when the American government, headed by President Martin Van Buren, instructed the volunteers that they would be prosecuted as criminals if they participated in the planned invasion, and many volunteers returned home.

On December 29, Canadian volunteers led by Col. Allan MacNab bombarded Navy Island, while British troops led by Capt. Andrew Drew of the Royal Navy cut lose the American ship SS Caroline from its moorings and set it alight, as it had been supplying Navy Island.[11] The action was undertaken based on information supplied by Alexander McLeod.

While this was going on, Mackenzie had travelled to Buffalo, seeking medical attention for his sick wife. While there, he was arrested for violating American neutrality laws, but was released on bail and returned to Navy Island in January. Van Rensselaer had grown disillusioned, however, and on January 14, 1838, he and his volunteers withdrew from Navy Island to American soil whereupon they were arrested for being in breach of American neutrality[12]

Years in the USA, 1838–1849

With the collapse of his Navy Island scheme, Mackenzie settled in New York City in January 1838, with his family joining him in April. In May, he launched a new newspaper, Mackenzie's Gazette, which was initially successful because the Rebellions of 1837 had created American interest in Canadian affairs. In January 1839, he moved to Rochester, New York, and spent several months trying to encourage Canadian exiles to launch a second invasion of Upper Canada, but had no success and eventually returned to New York City. Mackenzie was now determined to settle permanently in the United States, taking the first steps towards American citizenship. For the first time ever, Mackenzie now editorialized on internal American politics. He denounced Martin Van Buren as a tool of British imperialism because his government had issued a neutrality proclamation.

The trial for Mackenzie's violation of American neutrality laws in January 1838 was finally held in June 1839. Mackenzie was sentenced to pay a $10 fine and spend 18 months in jail. Mackenzie attempted to continue to publish Mackenzie's Gazette from jail, but it appeared only erratically. Soon, the unhealthy conditions of the jail led to a deterioration in Mackenzie's health. Throughout 1839, he and his supporters now petitioned President Van Buren, Governor of New York William H. Seward, United States Attorney General Felix Grundy, and United States Secretary of State John Forsyth. Van Buren was initially reluctant to pardon Mackenzie because he did not want to offend the British, but he eventually acquiesced and Mackenzie was pardoned in May 1840, after he had served less than a year in jail.

Mackenzie's stint in prison seems to have soured him on the United States. He continued to attack Van Buren and the British in the pages of the Gazette, but his editorials now also frequently included denunciations of American life for not being what it claimed. Desiring to return to Canada, he asked influential Reformers such as Isaac Buchanan to lobby for amnesty for Mackenzie and the rebels. In the meantime, the Gazette was struggling, in spite of Mackenzie's friendship with prominent American newspapermen like Horace Greeley, and Mackenzie was forced to shut down the paper in December 1840. In April 1841, he launched a newspaper in Rochester, The Rochester Volunteer. In it, he attempted to whip up fever for a war between the United States and Britain over the issue of Alexander McLeod, a Canadian who had been arrested in New York State in November 1840 for his role in the Caroline incident. The American public was not interested, however, and McLeod was acquitted. The Volunteer failed in September 1841, and in June 1842, Mackenzie moved back to New York City.

There, his money problems forced him to take a job as actuary and librarian at the Mechanics’ Institute. Mackenzie became an American citizen in May 1843. Throughout 1843, he worked on a biography of 500 Irish patriots, entitled, The Sons of the Emerald Isle (the first volume of which appeared in 1844) and in fall 1843 quit his job at the Mechanics' Institute to launch a new newspaper, the Examiner, which failed after just five issues. In July 1844, he managed to secure a patronage appointment as a customs clerk in the New York Custom House, but he resigned in June 1845 when Cornelius Van Wyck Lawrence was appointed Collector of the Port of New York and Mackenzie disagreed with his more conservative political views.

While Mackenzie was working at the Custom House, he copied out the papers of Jesse Hoyt, a customs official associated with Van Buren and the Albany Regency. Mackenzie published these papers, selling 50,000 copies, though Mackenzie himself did not make any money from the book, and he was criticized for publishing private papers solely to discredit his political enemies.

In 1846, Mackenzie published the second volume of The Sons of the Emerald Isle, as well as a highly critical biography of Martin Van Buren, whom Mackenzie despised.

In May 1846, Mackenzie's friend Horace Greeley asked him to travel to Albany to report on the state constitutional convention for the New York Tribune. The convention produced a radical constitution for New York State, establishing many new elected offices and resulting in the abolition of the Court of Chancery. In his later years, Mackenzie was much influenced by what he saw at the 1846 New York constitutional convention. Mackenzie stayed in Albany, editing the Albany Patriot until spring 1847 when he returned to New York City to work for the Tribune and to edit almanacs for Horace Greeley.

Final years in Canada, 1849–1861

In 1848, the Province of Canada (which had been formed out of Upper and Lower Canada in 1841 upon the recommendation of Lord Durham) received responsible government, with Lord Elgin being the first Governor General of the Province of Canada to accept the Legislative Assembly's advice as to whom to appoint to the Executive Council and hence the cabinet, instead of appointing the cabinet himself. In the elections for the 3rd Parliament of the Province of Canada, the Reformers won, and Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine became Joint Premiers of the Province of Canada. The Baldwin-Lafontaine ministry enacted sweeping reforms in the Province of Canada, which included an amnesty act for the rebels of 1837, which passed the Legislative Assembly in February 1849. Mackenzie wrote to his old friend James Leslie, who was now the Provincial Secretary, asking to be included in the amnesty.

In March 1849 Mackenzie reached Toronto where he visited John McIntosh, the father in law of William Lyon Mackenzie. Rumours spread and as the evening set in dirty, ragged, and intoxicated men began to assemble in front of the McIntosh property until several hundreds of Torontonians had gathered. Despite a police presence the mob attacked the home, throwing bricks and rocks. There were no injuries and by 4 o’clock in the morning, the mob left the McIntosh house and went to the residence of George Brown, of the Globe, smashing his windows and blinds. The next night another crowd gathered at John McIntosh’s home, but two hundred special constables were on hand, reinforced by 60 soldiers and many private citizens. This deterred violence and the night resulted in nothing but noisy demonstrations. The next night another mob gathered but they targeted the unpatrolled Bay and Bond streets, smashing gas lamps and windows. This was the last display of violence against William Lyon Mackenzie.[13] He frequented the shop C. A. Backas, a bookseller and newsdealer, and would regale any friend he met with reminisces of the rebellion in a nook at the south end of the counter.[14]

Mackenzie immediately went on a cross-country tour from Montreal to Niagara Falls, noting that he was happy to be allowed to visit. At the time, he insisted that he had no desire to return permanently, and he briefly accepted a position as the New York Daily Tribune's correspondent in Washington, D.C., but by April 1850, his desire to return to Canada was too great, and he moved back to Toronto in May. Mackenzie continued to write for the Tribune, and for the Niagara Mail and the Toronto Examiner (owned by James Leslie) and attempted to collect money that he believed he was owed for his public service in the 1830s.

In response to the Indian Mutiny, Mackenzie initially wrote in support of the rebels.[15] He argued that "the inhabitants of Hindostan" were as capable of civilisation as "the Celt or Anglo-Saxon", but not the "woolyhaired African".[16] Later he became more evenhanded writing that "[t]here is cruelty on both sides" and asked, "Which has the most reason to be cruel? The strangers who seek to trample India for gain, or the natives whose home is there?"[17]

Return to the Legislature, 1851–1858

Mackenzie took advantage of his notoriety to resume a career in politics. He ran in a by-election for the seat of Haldimand County in the 3rd Parliament of the Province of Canada. He won the election, defeating George Brown, the owner of the Toronto Globe, partially because Brown's well-known anti-Catholic views did not play well in a riding with a large number of Catholics.

For the next seven years, Mackenzie was the loudest advocate in the Assembly for the cause of "true reform". This involved a resumption of several of his political stances from the 1830s, including opposition to the clergy reserves and to state funding of religious colleges, and calls for abolishing the Court of Chancery. He now also became an opponent of government overspending, and was especially critical of state aid for railways, especially when those railways were monopolies. He repeatedly introduced a simplified legal code which he had drafted, but this never passed the Assembly.

As a "true reformer", Mackenzie was opposed to many of his Reform colleagues, whom Mackenzie labelled "sham reformers". One of the first victims of Mackenzie's ire was Robert Baldwin, who was forced to resign as Co-Premier in 1851, partially because of Mackenzie's report on the Court of Chancery in which he revealed that William Hume Blake had used the 1849 reorganization of the Court of Chancery to line his own pockets. When Mackenzie and Leslie subsequently campaigned against Baldwin in the October 1851 elections for the 4th Parliament of the Province of Canada, they were thus largely responsible for Baldwin and several other Reformers losing their seats, and Francis Hincks and Augustin-Norbert Morin becoming co-premiers.

In 1852, Hincks asked Mackenzie to participate in his negotiations with George Brown's Clear Grits, who Hincks hoped would rejoin the Reform Party, but Mackenzie refused out of a desire to maintain his freedom of action. Once Mackenzie's old friend John Rolph entered the Hincks-Morin ministry, he offered Mackenzie a plum job in Haldimand County, but Mackenzie refused, saying that he would not burden the Canadian taxpayers with an unnecessary post.

This period saw Mackenzie progressively alienate all of his old friends and allies. In late 1852, he had a falling-out with James Leslie after Lesslie refused to publish an intemperate letter on crown lands policy in Leslie's newspaper, the Toronto Examiner. In May 1853, Mackenzie turned his full wrath against Hincks when it was revealed that Hincks and John George Bowes had stolen from the public in a railway debenture scheme known as the "£10,000 Job". He even turned on John Rolph and his Lower Canadian ally Malcolm Cameron, whom he now accused of selling out the cause of reform. His final break with Rolph came in April 1854, when he published a denunciation of Rolph in Mackenzie's Weekly Message (which he had founded in 1852) in which he accused Rolph of treason during the 1837 rebellion. Although Mackenzie would have appeared to be a natural ally of George Brown and the Clear Grits, who similarly denounced the Reform Party for "selling out" the cause of reform, Mackenzie despised the Clear Grits because of their "hypocrisy" and because of Brown's anti-Catholic prejudices. Several Reform politicians continued to attempt to reach out to Mackenzie, but he rebuffed all of them, to the point that by 1857, only David Christie still attempted to include Mackenzie in Reform Party plans.

In the years 1854–1857, Mackenzie proposed an ambitious series of reforms in the Assembly, including a proposal to convert to decimal currency and to have mayors elected directly instead of by city councils. He also supported legislation with widespread support such as the abolition of the clergy reserves, the election of legislative councillors, privately financed railways, and reciprocity.

In 1854, Mackenzie's old enemy, Allan MacNab (or Sir Allan MacNab, as he now was), became co-premier of the Province of Canada. As chairman of the finance committee during 1854–55, Mackenzie was able to expose financial mismanagement and misuse of patronage by MacNab and Attorney General John A. Macdonald. Mackenzie now came to believe that the union of the two Canadas had been such a disaster that he thought it was no longer reformable.

As at many points in his life, Mackenzie continued to suffer from financial difficulties. James Leslie, who had reconciled with Mackenzie, organized a fund to "reward" Mackenzie for his years of service to Canada, ultimately raising $7,500, which Mackenzie used to buy a house and to secure a loan for his newspaper.

His health failing, and his confidence in the reform movement gone, Mackenzie resigned his seat in the Legislative Assembly in August 1858.

Final years, 1858–1861

By 1858, Mackenzie advocated annexation of Canada by the United States and pushed this position regularly in the Message. The paper no longer even covered Canadian politics at all. By 1861, his mood had improved somewhat, and he now proposed some sort of federal union between Britain, Canada, the United States, and Ireland. He reconciled with George Brown and the two enjoyed friendly relations.

Mackenzie died on August 28, 1861, following an apoplectic seizure. He died at his home in which he had lived since 1858 at 82 Bond Street in Toronto, and was buried at Toronto Necropolis. His house was recognized as a historic site in 1936 and became a museum. Toronto's William Lyon Mackenzie Collegiate Institute was named after him.

Bibliography of major works

- The history of the destruction of the Colonial Advocate Press by officers of the provincial government of Upper Canada and law students of the Attorney & Solicitor General ... (1827)

- Catechism of education: part first, various definitions of the term, education, qualities of mind, to the production of which education should be directed ... political education

- Sketches of Canada and the United States (1833)

- Mackenzie's own narrative of the late rebellion (1838)

- The sons of the Emerald Isle, or, Lives of one thousand remarkable Irishmen: including memoirs of noted characters of Irish parentage or descent (1845)

- The lives and opinions of Benj'n Franklin Butler, United States district attorney for the southern district of New York; and Jesse Hoyt, counsellor at law, formerly collector of customs for the port of New York; with anecdotes or biographical sketches of Stephen Allen; George P. Barker [etc] .. (1845)

- The life and times of Martin Van Buren: the correspondence of his friends, family and pupils (1846)

Miscellaneous

- William Lyon Mackenzie was the grandfather of William Lyon Mackenzie King, Canada's Prime Minister during World War II and its longest serving Prime Minister.

- William Lyon Mackenzie Collegiate Institute, a Toronto high school was named for him. Their mascot is a "Lyon".

- Toronto Fire Services fire boat William Lyon Mackenzie (fireboat) is also named in his honour.

- Mackenzie's early 19th century home in Queenston, Ontario has been restored and is now the Mackenzie Printery and Newspaper Museum. The museum includes a working mid 19th century printing shop, and features displays of printing equipment and technology ranging over a 500-year period. The museum is operated by the Niagara Parks Commission.

- "The Rebel Mayor", a Twitter account which posted satirical comments on various candidates in Toronto's 2010 mayoral election, was written in the persona and voice of Mackenzie.[18] The feed was eventually revealed to have been written by Shawn Micallef, a journalist for the publications Eye Weekly and Spacing.[19]

References

- 1 2 Gates 1996, p. 12.

- ↑ Gray 1998, p. 14.

- 1 2 Lindsey 1910, p. 34.

- ↑ Schrauwers 2009, p. 135.

- ↑ Romney, Paul (1987). "From the Types Riot to the Rebellion: Elite Ideology, Anti-legal Sentiment, Political Violence, and the Rule of Law in Upper Canada". Ontario History. LXXIX (2): 114.

- ↑ Peppiatt, Liam. "Chapter 35: The Red Lion Hotel". Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto Revisited.

- ↑ "The seventh report from the Select Committee of the House of Assembly of Upper Canada on grievances..."

- ↑ Schrauwers 2009, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Schrauwers 2009, p. 198.

- 1 2 Peppiatt, Liam. "Chapter 21: Jonathan Scott's House". Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto Revisited.

- ↑ Flint, David (1971). William Lyon Mackenzie - Rebel Against Authority. Toronto: Oxford University Press. p. 166. ISBN 0-19-540184-0.

- ↑ Flint, David (1971). William Lyon Mackenzie - Rebel Against Authority. Toronto: Oxford University Press. p. 168. ISBN 0-19-540184-0.

- ↑ Peppiatt, Liam. "Chapter 4: John McIntosh's House". Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto Revisited.

- ↑ Peppiatt, Liam. "Chapter 33: The Checkered Store". Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto Revisited.

- ↑ Message, July 17, 1857, August 14, 1857

- ↑ Message, February 5, 1858

- ↑ Message, September 18, 1857

- ↑ Sufrin, Jon (May 20, 2010). "The best of Rebel Mayor: the funniest quips from city hall's mystery tweeter, who was unmasked (sort of) this week". Toronto Life. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ↑ Grant, Kelly (November 5, 2010). "Revealed: The true identity of Twitter's Rebel Mayor". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

Works cited

- Gates, Lilian F. (1996). After the Rebellion: The Later Years of William Lyon Mackenzie. Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55488-069-0.

- Gray, Charlotte (1998). Mrs. King: the life and times of Isabel Mackenzie King. Toronto: Penguin Canada. ISBN 978-0-14-025367-2. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- Lindsey, Charles (1910). William Lyon MacKenzie. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4179-3806-3.

- Schrauwers, Albert (2009). Union is Strength: W. L. Mackenzie, the Children of Peace and the Emergence of Joint Stock Democracy in Upper Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9927-3.

Further reading

- "Patrick Swift" (William Lyon Mackenzie), A New Almanack for the Canadian True Blues... (2nd ed., 1833)

- William Lyon Mackenzie, Sketches of Canada and the United States (1833)

- Upper Canada, House of Assembly, The Seventh Report from the Select Committee on Grievances... (1835)

- William Lyon Mackenzie, Mackenzie’s Own Narrative of the Late Rebellion, With Illustrations and Notes, Critical and Explanatory... (1838)

- F. B. Head, A Narrative (1839)

- William Lyon Mackenzie, The Sons of the Emerald Isle, or, Lives of One Thousand Remarkable Irishmen... (1844)

- William Lyon Mackenzie, Lives and Opinions of Benjamin Franklin Butler and Jesse Hoyt (1845)

- William Lyon Mackenzie, Life and Times of Martin Van Buren (1846)

- Charles Lindsay, Life and Times of William Lyon Mackenzie (1862; new edition, 1908, in "The Makers of Canada Series")

- J. C. Dent, Story of the Upper Canadian Rebellion (1885)

- John King (Mackenzie's son-in-law), The Other Side of the Story (1886) – responding to Dent

- D. B. Read, The Canadian Rebellion of 1837 (1896)

- Robina and K. M. Lizars, Humours of ‘37, Grave, Gay, Grim: Rebellion Times in the Canadas (1897)

- William Kingsford, The History of Canada, Vol. X (1898)

- Stephen Leacock, Mackenzie, Baldwin, LaFontaine, Hincks: Responsible Government (1907)

- G. G. S. Lindsey (Mackenzie's grandson), William Lyon Mackenzie (1909)

- Aileen Dunham, Political Unrest in Upper Canada, 1815–1836 (1927)

- R. A. MacKay, "The Political Ideas of William Lyon Mackenzie", Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science 3 (1937)

- J. J. Talman, The Printing Presses of William Lyon Mackenzie, Prior to 1837 (1937)

- William Kilbourn, The Firebrand: William Lyon Mackenzie and the Rebellion in Upper Canada (1956), Clarke, Irwin and Company, Toronto.

- S. D. Clark, Movements of Political Protest in Canada, 1640–1840 (1959)

- L. F. Gates, "The Decided Policy of William Lyon Mackenzie", Canadian Historical Review 40 (1959)

- Eric Jackson, "The Organization of Upper Canadian Reformers, 1818–1867," Ontario History 53 (1961)

- John Moir, "Mr. Mackenzie’s Secret Reporter", Ontario History 55 (1963)

- F. H. Armstrong, "The York Riots of March 23, 1832", Ontario History 55 (1963)

- L. F. Gates, "Mackenzie's Gazette: An Aspect of W. L. Mackenzie’s American Years,” Canadian Historical Review 46 (1965)

- J. Edgar Rea. "Rebellion in Upper Canada, 1837" Manitoba Historical Society Transactions Series 3, 22 (1965–66) online, historiography

- John Robert Colombo, ed., William Lyon Mackenzie Rides Again! (1967) – primary documents

- F. C. Hamil, "The Reform Movement in Upper Canada", in Profiles of a Province: Studies in the History of Ontario... (1967)

- L. F. Gates, "W. L. Mackenzie’s Volunteer and the First Parliament of United Canada", Ontario History 59 (1967)

- John Ireland, "Andrew Drew: The Man who Burned the Caroline", Ontario History 59 (1967)

- F. H. Armstrong, "Reformer as Capitalist: William Lyon Mackenzie and the Printers’ Strike of 1836", Ontario History 59 (1967)

- F. H. Armstrong, "William Lyon Mackenzie, First Mayor of Toronto: A Study of a Critic in Power", Canadian Historical Review 48 (1967)

- J. E. Rea, "William Lyon Mackenzie – Jacksonian?", Mid-America: An Historical Quarterly 50 (1968)

- David Flint, William Lyon Mackenzie: Rebel Against Authority (1971)

- F. H. Armstrong, "William Lyon Mackenzie: The Persistent Hero", Journal of Canadian Studies 6.3 (1971)

- Anthony W. Rasporich, William Lyon Mackenzie (1972)

- Rick Salutin, 1837, The Farmers' Revolt (1976) – play

- Lillian F. Gates, William Lyon Mackenzie: The Post-Rebellion Years in the United States and Canada (1978)

- William Dawson LeSueur, William Lyon Mackenzie: A Reinterpretation (1979)

- Lillian F. Gates, After the Rebellion: The Later Years of William Lyon Mackenzie (1988)

- Chris Raible, Muddy York Mud: Scandal & Scurrility in Upper Canada (1992)

- Charlotte Gray, Mrs. King: The Life and Times of Isabel Mackenzie King (1997)

- Chris Raible, A Colonial Advocate: The Launching of His Newspaper and the Queenston Career of William Lyon Mackenzie (1999)

- John Sewell, Mackenzie: A Political Biography of William Lyon Mackenzie (2002)

- Jackes, Lyman B. Tales of North Toronto. Toronto: North Toronto Business Men's Association, 1948. Print.

External links

- Frederick H. Armstrong and Ronald J. Stagg . "MACKENZIE, WILLIAM LYON," in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography

- Buffalonian article on the Canadian Rebellion

- The History of the Battle of Toronto by William Lyon MacKenzie, 1839 from the Ontario Time Machine

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by new post replacing the Chairman of the Home District Council |

Mayor of Toronto 1834 |

Succeeded by Robert Baldwin Sullivan |

| Preceded by none – new movement |

Leader of the Reform Party of Upper Canada 1824?–1838 |

Succeeded by Robert Baldwin |