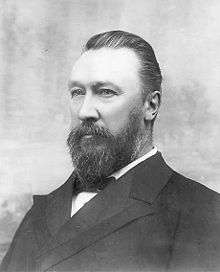

William Lyne

| The Honourable Sir William John Lyne KCMG | |

|---|---|

| |

| 13th Premier of New South Wales | |

|

In office 14 September 1899 – 27 March 1901 | |

| Preceded by | George Reid |

| Succeeded by | John See |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for Hume | |

|

In office 29 March 1901 – 31 May 1913 | |

| Preceded by | New division |

| Succeeded by | Robert Patten |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

6 April 1844 Apslawn, Colony of Tasmania |

| Died |

3 August 1913 (aged 69) Double Bay, New South Wales, Australia |

| Nationality | British subject |

| Political party |

Protectionist (1901–09) Independent (1909–13) |

| Occupation | Clerk, landowner |

Sir William John Lyne KCMG (6 April 1844 – 3 August 1913), Australian politician, was Premier of New South Wales and a member of the first federal ministry. As premier, Lyne presided over the passage of progressive legislation for miners' accident relief, shearers' accommodation, and aged pensions, together with the introduction of the early closing of shops.[1]

Early life

Lyne was born at Apslawn, Tasmania. He was the eldest son of John Lyne, a property owner, who would be a member of the Tasmanian House of Assembly from 1880 to 1893.[2] He was educated at Horton College, Ross, and subsequently by a private tutor. He left Tasmania at 20 to take up land in northern Queensland, but finding the climate did not suit him, he returned to Tasmania a year later. He became a clerk at Glamorgan Council. After 10 years, Lyne left for the mainland again in 1875 and took up land at Cumberoona near Albury, New South Wales.[3]

State politics

- See also: Lyne ministry

Lyne was the member for Hume in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly from 1880. A Protectionist, he was Secretary for Public Works in 1885 and from 1886 to 1887 and Secretary for Lands in 1889.[4] From 1891 to 1894, he became Secretary for Public Works again in the third ministry of George Dibbs. Lyne was a strong protectionist and fought hard for a high tariff. He also strongly supported railway expansion and pressed on with the building of the Culcairn to Corowa line in his own electorate.[5]

The Free Trade Party was still very strong in New South Wales, and George Reid won the 1895 election and Lyne became Leader of the Opposition due to Dibbs losing his seat. Reid had entrusted John Cash Neild with a preparation of a report upon old age pensions, and he had promised the leader of the Labor Party that he would give Neild no payment for this without the sanction of Parliament. Finding that the work was much greater than he expected, Neild had asked for and obtained an advance in anticipation of a vote. Lyne, by a clever amendment of a vote of want of confidence, made it practically impossible for the Labor party to support Reid, thus aligning the Labor Party who held the balance of power against Reid. Lyne became Premier by agreeing to reforms proposed by the Labor Party.[3][6] Lyne promised the Labor Party specific reforms and he passed 85 Acts between July and December 1900, including early closing of retail shops, coal mines regulation and miners' accident relief, old-age pensions and graduated death duties.[5]

Lyne was a consistent opponent of the Federation of Australia until the establishment of the Commonwealth in 1901. He was one of the representatives of New South Wales at the 1897 convention and sat on the finance committee but did not have an important influence on the debates. When the campaign began before the referendum of 1898, Lyne declared himself against the bill, and, at the second referendum, held in 1899 he was the only New South Wales convention representative who was still dissatisfied with the amended bill. Reid, after some vacillation had, however, declared himself whole-heartedly on the side of federation, and the referendum showed a substantial majority on the "Yes" side.[3]

Federal politics

As Premier of the largest colony, Lyne considered himself entitled to be the first Prime Minister of Australia when the colonies federated in January 1901. In December 1900 the Governor-General, Lord Hopetoun, offered the post to Lyne; but because Lyne had opposed federation, most senior politicians, notably Alfred Deakin, told Hopetoun that they would not serve under Lyne. Hopetoun was forced to accept the majority view that Edmund Barton, the leader of the federation movement, should be Prime Minister.

Lyne became Minister for Home Affairs in Barton's cabinet on 1 January 1901 and was elected to the first federal Parliament as member for the Division of Hume in March 1901. He was responsible for the Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 (preceded the Commonwealth Electoral Act), including the introduction of women's suffrage and the establishment of the Commonwealth Public Service.[5] He remained Minister for Home Affairs until Charles Kingston left the cabinet, and became Minister for Trade and Customs in his stead on 7 August 1903. He retained this position when Deakin became Prime Minister towards the end of September. The general election held in December 1903 resulted in the return of three nearly equal parties, and Deakin was forced to resign in April 1904 but came back into power in July 1905 with Lyne in his old position.

In April 1907 Lyne accompanied Deakin to the colonial conference and endeavoured to persuade the British politicians that they were foolish in clinging to their policy of free trade. Deakin and Lyne returned to Australia in June, and when Sir John Forrest resigned his position as Treasurer at the end of July 1907, Lyne succeeded him.[3]

Fusion government

In November 1908, the Labor party withdrew its support from Deakin, and Fisher succeeded him and held office until June 1909, when Deakin and Cook joined forces and formed the so-called "Fusion" government. Lyne accused Deakin of betrayal, and thereafter sat as an independent Protectionist. His bitter denunciations of his one-time friend continued during the 11 months the ministry lasted but Deakin did not respond. The Labor Party came in with a large majority in the April 1910 election, and Lyne was elected as a pro-Labor independent. However, Lyne lost his seat in the May 1913 election when the Labor Party lost to the opposition Commonwealth Liberal Party.

Lyne died in the Sydney suburb of Double Bay, a few months afterwards. He married twice and was survived by one son and three daughters of the first marriage and by Lady Lyne and her daughter.[3]

Assessment

Lyne was more of a politician than a statesman, always inclined to take a somewhat narrow view of politics. He did some good work when Premier of New South Wales by putting through the Early Closing bill (regulating shopping hours), the Industrial Arbitration bill, and bringing in graduated death duties; but even these measures were part of his bargain with the Labor party.

He was tall and vigorous, in his younger days a typical Australian bushman. He knew everyone in his electorate and was a good friend to all. He was bluff and frank and it was said of him that he was a man whose hand went instinctively into his pocket when any appeal was made to him. In Parliament, he was courageous and a vigorous administrator.

Scarcely an orator, he was a good tactician. Although overshadowed by greater men like Barton, Reid and Deakin, his views had much influence in his time. In his early political life he was a great advocate of irrigation, and in federal politics he had much to do with the shaping of the policy of protection eventually adopted by the Commonwealth.[3]

His reputation has been badly affected by Alfred Deakin's description of him as "a crude, sleek, suspicious, blundering, short-sighted, backblocks politician".[5]

Honours

Lyne was created KCMG in 1900.[3] The Federal electoral Division of Lyne and the Canberra suburb of Lyneham are named after him.

See also

References

- ↑ Ross McMullin, The Light on the Hill: The Australian Labor Party 1891–1991

- ↑ "John Lyne". The Parliament of Tasmania from 1856. Parliament of Tasmania. 2005. Retrieved 20 August 2007. and "Electorate of Apsley – History". Parliament of Tasmania. 2007. Archived from the original on 1 September 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Serle, Percival. "Lyne, Sir William John (1844–1913)". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Project Gutenberg Australia. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ↑ "Sir William John Lyne (1844–1913)". Members of Parliament. Parliament of New South Wales. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Cunneen, Chris (1986). "Lyne, Sir William John (1844–1913)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 14 April 2007.

- ↑ Childe, Vere Gordon (1923). "Chapter II. The Theory and Practice of Caucus Control". How Labour Governs. www.marxist.org. Retrieved 20 August 2007.