William Henry Irwin

William Henry "Will" Irwin (1873–1948) was an American author, writer and journalist who was associated with the muckrakers.

Biography

Early life

Irwin was born September 14, 1873 in Oneida, New York. In his early childhood the Irwin family moved to Clayville, New Jersey, a farming and mining center south of Utica. In about 1878 his father moved to Leadville, Colorado, establishing himself in the lumber business, and brought his family out. When his business failed Irwin's father moved the family to Twin Lakes, Colorado. A hotel business there failed too, and the family moved back to Leadville, to a bungalow at 125 West Twelfth Street. In 1889 they moved to Denver, where he graduated from high school. He cured himself of a diagnosed bout of tuberculosis by "roughing it" for a year as a cowboy.[1]

Life at Stanford University

With a loan from his high school teacher Irwin entered Stanford University in September 1894. According to journalism historians Clifford Weigle and David Clark in their biographical sketch of Irwin,

- "During four riotous years at Stanford, Irwin 'specialized' in campus politics, undergraduate theatricals and writing, and beer drinking and inventive pranks. Expelled three weeks before he was to have received the B.A. degree in 1898, he got the degree a year later after final, solemn consideration by a somewhat reluctant faculty committee on student affairs."[2][3]

Irwin was forced to withdraw for disciplinary reasons but was readmitted and graduated on May 24, 1899.[4]

Reporting

In 1901 Irwin got a job as a reporter on the San Francisco Chronicle, eventually rising to Sunday editor. For the San Francisco-based Bohemian Club, he wrote the Grove Play The Hamadryads in 1904. That same year he moved to New York City to take a reporter's position at The New York Sun, then in its heyday under the editorship of Chester Lord and Selah M. Clark.

Irwin arrived in New York City the same day as a major disaster—the sinking of the General Slocum. A new reporter on The Sun, he was assigned to work the Bellevue morgue, where the more than 1,000 bodies of the victims of fire and drowning were taken.[1][5]

The City That Was

Irwin's biggest story and the feat that made him a professional writer was his absentee coverage for the The New York Sun of the San Francisco earthquake of April 18, 1906. Weigle and Clark describe his activities as follows:

- "Because he knew the city so well, he was assigned to write – mostly from memory, supplemented by scant telegraphic bulletins – the story of the quake. Before the last-edition deadline on the first day, April 18, 1906, he wrote fourteen columns of copy. and he kept writing, eight columns or more a day, for the next seven days, as fire swept the ruined city. The booklet, for which Irwin is most widely known, resulted from six or seven columns of general description of pre-earthquake San Francisco that he wrote on the afternoon of the third day of the story."[6]

Irwin was hired by S.S. McClure in 1906 as managing editor of McClure's. He rose to the position of editor but disliked the work and then moved to Collier's, edited by Norman Hapgood. He wrote investigative stories on the movement for Prohibition and a study of fake spiritual mediums.

Back on the Pacific coast in 1906–1907 to research a story on anti-Japanese racism Irwin returned to San Francisco and found it flourishing. Several years later, he wrote an article on the city's rebirth entitled "The City That Is" in the San Francisco Call, which concluded that San Francisco had become "a larger city, a more convenient city, and since it is also a more beautiful and more distinctive city I announce myself a complete convert. This city that was business is the old stuff."[7]

Irwin's series on anti-Japanese discrimination appeared in Collier's in September–October 1907 and Pearson's in 1909.[8]

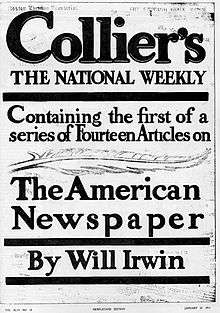

"The American Newspaper"

Then came the series "The American Newspaper". In 1911 Irwin published one of the most famous critical analyses of American journalism. The series, titled "The American Newspaper", was researched from September 23, 1909, until late June 1910, and published in Collier's magazine from January to June 1911.[1]

World War I

Irwin continued to write articles, some in the muckraking style, until the outbreak of World War I. He sailed to Europe in August 1914 as one of the first American correspondents. According to media historians Edwin and Michael Emery,

- "[Irwin's] beats on the battles of Ypres and the first German use of poison gas were also printed in the Tribune. Irwin was one of several correspondents who represented American magazines in Europe; he first wrote for Collier's and then for the Saturday Evening Post.[9] Irwin's article appeared on the front page of The New York Tribune on April 27, 1915.[10]

Irwin served on the executive committee of Herbert Hoover's Commission for Relief in Belgium in 1914–1915 and was chief of the foreign department of George Creel's Committee on Public Information in 1918.

Later life

During and after the war Irwin wrote 17 more books, including a biography of Herbert Hoover, a history of Paramount Pictures and its founder Adolph Zukor, The House That Shadows Built (1928), and his autobiography, The Making of a Reporter (1942). He also wrote two plays and continued magazine writing.

He was married to the feminist author Inez Haynes Irwin, who published under the name Inez Haynes Gilmore, author of Angel Island (1914) and The Californiacs (1916).[11][12]

Death

Will Irwin died on February 24, 1948, at the age of 74.

See also

- Christ or Mars? (1923).

- The House That Shadows Built (1931). —Paramount Pictures promotional film which took its name from Irwin's book.

- The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science (1909), based on McClure's articles that Irwin helped to research

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Robert V. Hudson. The Writing Game. A Biography of Will Irwin. Ames, IA: The Iowa State University Press, 1982.

- ↑ "About Will Irwin." In Will Irwin, The American Newspaper. A Series First Appearing in COLLIERS, January – July 1911. With comments by Clifford J. Weigle and David Clark. Ames, IO: The Iowa State University Press, 1969, pp. ix–x.

- ↑ "Class of '99 Bids Farewell to Alma Mater. Stanford Men and Women Who Go Forth to Fight Life's Battles." The San Francisco Call Tuesday May 23, 1899, p.2.

- ↑ Irwin is sometimes said to have been a member of the Stanford Chaparral. But Irwin graduated on May 24, 1899, while the first issue of The Chappie was published in October of that year. See Robert V. Hudson. The Writing Game. A Biography of Will Irwin. Ames, IA: The Iowa State University Press, 1982, p. 19.

- ↑ "49 More Bodies; 680 in All." The Sun June 20, 1904, p.5

- ↑ The City That Was. A requiem of Old San Francisco. By Will Irwin

- ↑ San Francisco Call March 12 1910, p. 12.

- ↑ "The Japanese and the Pacific Coast," Collier's, 40 (September 28, 1907), 13–5; (October 12, 1907), pp. 13–5; (October 19, 1907), 17–9; (October 26, 1907), pp. 15–6; "Why the Pacific Slope Hates the Japanese," Pearson's, 21 (1909), pp. 581–91.

- ↑ Michael Emery, Edwin Emery, and Nancy L. Roberts. The Press and America. An Interpretive History of the Mass Media. Eighth Edition. Boston and London: Allyn and Bacon, 1996, p. 261.

- ↑ "Germans Use Blinding Gas to Aid Poison Fumes"

- ↑ "Fiction for February". The New York Times. February 1, 1914. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- ↑ The Californiacs by Inez Haynes Irwin at the Wayback Machine (archived November 29, 2007)

External links

- Works by Will Irwin at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Will Irwin at Internet Archive

- The City That Was: A requiem of Old San Francisco by Will Irwin

- Will Irwin at IMDB