Wild Westing

Wild Westing was the term used by Native Americans for their performing with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and similar shows. Between 1887 and World War I, over 1,000 Native Americans went “Wild Westing.”[1] Most were Oglala Lakota (Oskate Wicasa) from their reservation in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, the first Lakota people to perform in these shows.[2] During a time when the Bureau of Indian Affairs was intent on promoting Native assimilation, Col. William Frederick Cody ("Buffalo Bill") used his influence with U.S. government officials to secure Native American performers for his Wild West. Col. Cody treated Native American employees as equals with white cowboys.

Wild Westers received good wages, transportation, housing, abundant food, and gifts of cash and clothing at the end of each season. Wild Westing was very popular with the Lakota people and benefited their families and communities. Wild Westing offered opportunity and hope during time when people believed Native Americans were a vanishing race whose only hope for survival was rapid cultural transformation. Americans and Europeans continue to have a great interest in Native peoples and enjoy modern Pow-wow culture, traditional Native Americans skills; horse culture, ceremonial dancing and cooking; and buying Native American art, music and crafts. First begun in Wild West shows, Pow-wow culture is popular with Native Americans throughout the United States and a source of tribal enterprise. Wild Westers still perform in movies, pow-wows, pageants and rodeos. Some Oglala Lakota people carry on family show business traditions from ancestors who first worked for Buffalo Bill and other Wild West shows.

Vanishing race

During the Progressive Era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was an explosion of public interest in Native American culture and imagery. Newspapers, dime-store novels, Wild West shows, and public exhibitions portrayed Native Americans as a “vanishing race.” Their numbers had decreased since the Indian Wars, and survivors were struggling with poverty and constraints on Indian reservations. American and European anthropologists, who represented a new field, historians, linguists, journalists, photographers, portraitists and early movie-makers believed they had to study western Native American peoples. Many researchers and artists lived on government reservations for extended periods to study Native Americans before they “vanished.” Their inspired effort heralded the “Golden Age of the Wild West.” Photographers included Gertrude Käsebier, Frank A. Rinehart, Edward Curtis, Jo Mora and John Nicholas Choate, while portraitists included Elbridge Ayer Burbank, Charles M. Russell and John Hauser.

Progressive Era fight for the image

During the Progressive Era, U.S. government policy focused upon acquiring Indian lands, restricting cultural and religious practices and sending Native American children to boarding schools. Progressives agreed that the situation was serious and that something needed to be done to educate and acculturate Native Americans to white society, but they differed as to education models and speed of assimilation. Reformist progressives, a coalition led by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Society of American Indians and Christian organizations, promoted rapid assimilation of children through off-reservation Indian boarding schools and immersion in white culture.[3]

The Society of American Indians was opposed to Wild West shows, theatrical troupes, circuses and most motion picture firms. The Society believed that theatrical shows were demoralizing and degrading to Indians, and discouraged Indians from "Wild Westing." [4] Chauncey Yellow Robe wrote that “Indians should be protected from the curse of the Wild West show schemes, wherein the Indians have been led to the white man’s poison cup and have become drunkards.” [5]

Reformist progressives believed Wild West shows exploited Native Americans and vigorously opposed theatrical portrayals of Native Americans as savages and vulgar stereotypes.[6] From 1886 to the onset of World War I, reformist progressives fought a war of images with Wild West shows before public exhibitions at world fairs, expositions and parades portraying the model Carlisle Indian Industrial School as a new generation of Native Americans embracing civilization, education and industry.[7]

Public interest in Native American culture and imagery

Wild West shows were exceptionally popular in the United States and Europe. Here, the American and European public could see and hear some of the first Americans, not as curiosities, but a people with vibrant culture.[8] In 1893, over two million patrons saw Buffalo Bill’s Wild West perform during the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois.[9] “Buffalo Bill” Cody launched his Wild West traveling show in 1883, and was so successful there were fifty copies in two years.[10] Buffalo Bill toured the United States and Europe until his death in 1917. Wild West shows were "dime novels come alive." Millions of Americans and Europeans enjoyed the imagery and adventure of historic reenactments of the Battle of Little Big Horn; demonstrations of Lakota horse culture and equestrian skills; archery, ceremonial dancing, cooking and music. Visitors could stroll through model Indian tipi “villages” and meet performers; available for purchase were crafts from women artisans, and autographed postcards, photographs and memorabilia from famous Wild Westers.[11]

Between 1887 and World War I, over 1,000 Native Americans went “Wild Westing” with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West.[12] Most Wild Westers were Oglala Lakota from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, the first Lakota people to go Wild Westing.[13]

During a time when the Bureau of Indian Affairs was intent on promoting Native assimilation, Col. Cody used his influence with U.S. government officials to secure Native American performers for his Wild West. Buffalo Bill treated Native American employees as equals with white cowboys. Wild Westers received good wages, transportation, housing, abundant food, and gifts of cash and clothing from Buffalo Bill at the end of each season. Wild Westers were employed as performers, interpreters and recruiters. Men had money in their pockets and for their families on the reservation. Female performers were paid extra for infants and children, and supplemented wages by making and selling Lakota crafts.[14]

Sobriety and good conduct was required. Performers agreed to refrain from all drinking, gambling and fighting, and to return to his or her reservation at the end of each seasonal tour. Shows hired venerable elder male Indians to appear in the parades to ensure that young men acted with appropriate behavior when visiting host communities, and rules were self-policed by traditional Oglala Lakota chiefs and former U.S. Army Indian Scouts.[15]

Most performers spent one or two seasons on the road; some Wild Westers became cowboys, stuntmen for films, artisans, musicians, educators, authors, movie actors and entrepreneurs. Chief Flying Hawk was a veteran of Wild West shows over 30 years, from about 1898 to 1930.

Wild Westing was very popular with the Lakota people and beneficial to their families and communities. It offered a path of opportunity during a time when people believed Native Americans were a vanishing race, whose only hope for survival was rapid cultural transformation. It offered a safe haven for Lakota leadership after the Sioux Wars and for famous Native American prisoners of war. The touring also offered freedom six months each year from the degrading confines of government reservations. Wild Westing was an act of passive resistance to oppressive Bureau of Indian Affairs policies.[16]

Wild Westing was a means for the Lakota to preserve their culture and religion. Shows generally toured from late spring to late autumn, paralleling the traditional buffalo hunt season.[17] In performance, the Lakota performed dances banned at the time on reservations. Lakota dancers in the present day credit Cody and the Wild Westers for preserving dances that were otherwise suppressed. The Lakota easily adapted to historical reenactments of the traditional practice of continually reenacting their history in dance and rituals. By this means, the exploits of the warriors were indelibly inscribed upon the collective consciousness of the oyate, or nation. Wild Westers at times performed programs that dramatized the very battles, raids and massacres in which the men had participated as warriors.[18]

Wild Westing allowed individuals to draw their own conclusions and make decisions about their own lives.[19] It improved self-esteem and provided pleasure from performing for appreciative audiences.[20] It offered adventure; performers traveled to the great cities of the world and freely associated with new cultures. Inter-marriage was not uncommon and many performers settled in Europe, some traveling with other shows and circuses. Between daily performances, Wild Westers played games such as ping pong and dominoes, which they had adopted during European tours.[21]

Traveling and performing was hard work, and rest and relaxation was important. Performers were permitted to freely travel by automobile or by train, for shopping, sightseeing, visiting friends, attending parties and gala events.[22]

Wild Westers

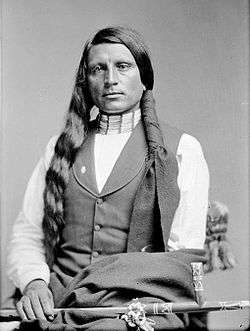

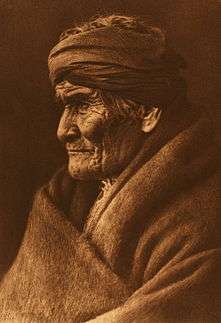

Wild westers educated the American and European public about Native American history and culture. The Wild Wester community was a diverse group, including U.S. Army Indian Scouts from the Great Sioux War; famous prisoners of war such as Lakota Chief Sitting Bull, Ghost Dancers Kicking Bear and Short Bull; Apache Chief Geronimo; Carlisle Indian School students Luther Standing Bear and Frank C. Goings; and Chiefs Iron Tail and Red Shirt, who became international celebrities. Chief Iron Tail was the most famous Native American of his day; a popular subject for professional photographers, he had his image circulated across the continents.[23] Chief Red Shirt was popular with journalists and newspapers and was the most quoted Wild Wester celebrity.[24] Early dime novels, Wild West shows and Golden Age photographers, portraitists and movie-makers created the theatrical image and portrayal of the Lakota people as the iconic American Indian mounted warrior. This popular perception in the United States and Europe was created by Lakota performers in their historic reenactments of the Sioux Wars; demonstrations of Lakota horse culture and equestrian skills; and ceremonial dancing, cooking and music.[25]

Carlisle Indian Industrial School

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, was the flagship Indian boarding school in the United States from 1879 through 1918. Carlisle was the first Indian boarding school located far from the reservation, in an Eastern environment free of the West’s anti-Indian prejudices and free from the influences of native cultures.[26]

Carlisle set the bar for 26 Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding schools in 15 states and territories and hundreds of private boarding schools sponsored by religious denominations. Over 10,000 Native American children from 140 tribes attended Carlisle. Tribes with the largest number of students included the Sioux, Chippewa, Seneca, Oneida, Cherokee, Apache, Cheyenne and Alaskan.[27] Carlisle offered a path of opportunity and hope at a time when people believed Native Americans were a vanishing race whose only hope for survival was rapid cultural transformation.[28]

Carlisle was founded on principle that Native Americans are the equals of whites and that Native American children immersed in white culture would learn skills to advance in society. Carlisle evolved beyond an industrial trade school. Nearby historic Dickinson College provided Carlisle Indian School students with visiting professors, access to the Dickinson Preparatory School ("Conway Hall") and college level education. The Dickinson School of Law was another resource to the Carlisle Indian School and a number of Carlisle students attended. Students excelled at music, debating, journalism and sports, and were offered internships and a summer outing program living with white families and earning wages. The Carlisle Indian Band, Carlisle Cadets and Carlisle Indians football team earned national reputations. The Carlisle Indian Band performed at world fairs, expositions, parades and every national presidential inaugural celebration until the school closed. The Carlisle Cadets at arms marched in parades. The Carlisle Indians were a national football powerhouse in the early 20th century and competed and won games against Harvard, Pennsylvania, Cornell, Dartmouth, Yale, Princeton, Brown, and Army and Navy. During the program's 25 years, the Carlisle Indians compiled a 167–88–13 record and 0.647 winning percentage, the most successful defunct major college football program. In 1911, the Indians posted an 11–1 record, which included one of the greatest upsets in college football history. Legendary athlete Jim Thorpe and coach Pop Warner led the Carlisle Indians to an 18–15 upset of Harvard before 25,000 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Thorpe scored all the points for Carlisle, a touchdown, extra point and four field goals.[29]

Attending Carlisle is considered by some Native Americans like going to Yale, Princeton or Cambridge, and the family tradition of Carlisle alumni as “Harvard style” is one of pride and stories of opportunity and success.[30] Carlisle was a unique school and produced a new generation of Native American leadership in the United States.[31]

Oglala Lakota Wild Westers

Wild Westing and the Carlisle Indian School were portals to education, opportunity and hope, and came at a time when the Lakota people were impoverished, harassed and confined. Most Wild Westers were Oglala Lakota from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, the first Lakota people to go Wild Westing.[32] Known as “Show Indians”, Oglala Wild Westers referred to themselves as Oskate Wicasa or "Show Man", a title of great honor and respect.[33] On March 31, 1887, Chief Blue Horse, Chief American Horse and Chief Red Shirt and their families boarded the S.S. State of Nebraska in New York City, led a journey for the Lakota people when they crossed the sea to England on Buffalo Bill’s first international tour to perform at the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria and in Birmingham, Salford and London over a five–month period. The entourage consisted of 97 Indians, 18 buffaloes, 2 deer, 10 elk, 10 mules, 5 Texas steers, 4 donkeys, and 108 horses.[34]

Since 1887, Wild Westing has been a family tradition with several hundred Pine Ridge families. Between 1906 and 1915, 570 individuals from Pine Ridge went Wild Westing with Buffalo Bill and other shows.[35] Often entire families worked together, and the tradition of the Wild Wester community is not unlike that of circus communities.[36] Frank C. Goings, the recruiting agent for Buffalo Bill and other Wild West shows at Pine Ridge, was a Carlisle alumnus and Wild Wester with experience as a performer, interpreter and chaperone.[37] Goings carefully chose the famous chiefs, the best dancers, the best singers, and the best riders; screened for performers willing to be away from home for extended periods of time; and coordinated travel, room and board.[38] Travelling with his wife and children, and for many years toured Europe and the United States with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Real West and the Sells Floto Circus.[39]

Carlisle Wild Westers

Many Oglala Lakota Wild Westers from Pine Ridge Reservation, South Dakota attended Carlisle.[40] Carlisle Wild Westers were attracted by the adventure, pay and opportunity and were hired as performers, chaperons, interpreters and recruiters. Wild Westers from Pine Ridge enrolled their children at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School from its beginning in 1879 until its closure in 1918. In 1879, Oglala Lakota leaders Chief Blue Horse, Chief American Horse and Chief Red Shirt enrolled their children in the first class at Carlisle. They wanted their children to learn English, trade skills and white customs. "Those first Sioux children who came to Carlisle could not have been happy there. But it was their only chance for a future."[41] Luther Standing Bear was taught to be brave and unafraid to die, and left the reservation to attend Carlisle and do some brave deed to bring honor to his family. Standing Bear’s father celebrated his son’s brave act by inviting his friends to a gathering and gave away seven horses and all the goods in his dry goods store.[42]

World fairs and expositions

During the Progressive Era, from the late 19th century until the onset of World War I, Native American performers were major draws and money-makers. Millions of visitors at world fairs, exhibitions and parades throughout the United States and Europe observed Native Americans portrayed as the vanishing race, exotic peoples and objects of modern comparative anthropology.[43] Reformists Progressives and the Society of American Indians fought a war of words and images against popular Wild West shows at world fairs, expositions and parades and opposed theatrical portrayals of Wild Westers as vulgar heathen stereotypes. In contrast, Carlisle students were portrayed as a new generation of Native American leadership embracing civilization, education and industry. The fight for the image of the Native American began when Reformist Progressives pressured organizers to deny Buffalo Bill a place at the Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, Illinois.[44] Instead, a feature of the Exposition was a model Indian school and an ethnological Indian village supported by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[45] In style, Buffalo Bill established a fourteen-acre swath of land near the main entrance of the fair for "Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World" where he erected stands around an arena large enough to seat eighteen thousand spectators. Seventy-four Wild Westers from Pine Ridge, South Dakota, who had recently returned from a tour of Europe, were contracted to perform in the show. Cody also brought in an additional one hundred Wild Westers directly from Pine Ridge, Standing Rock and Rosebud reservations, who visited the Exposition at his expense and participated in the opening ceremonies.[46] Over two million patrons saw Buffalo Bill’s Wild West outside the Columbian Exposition, often mistaking the show as an integral part to the World's Fair.[47]

The “vanishing race” theme was dramatized at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition of 1898 at Omaha, Nebraska, and The Pan-American Exposition of 1901 in Buffalo, New York. Exposition organizers assembled Wild Westers representing different tribes who portrayed Native Americans as a “vanishing race” at “The Last Great Congress of the Red Man”, brought together for the first and last time, apparently to commiserate before they all vanished.[48]

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904, known as the St. Louis World’s Fair, was the last of the great fairs in the United States before World War I. Organizers wanted their exotic people to be interpreted by anthropologists in a modern scientific manner portraying contrasting images of Native Americans.[49] A Congress of Indian Educators was convened and Oglala Lakota Chief Red Cloud and Chief Blue Horse, both eighty-three years old, and the best-known Native America orators at the St. Louis World's Fair, spoke to audiences. A model Indian School was placed on top on a hill so Indians below could see their future as portrayed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[50] On one side of the school, “blanket Indians”, men or women who refused to relinquish their native dress and customs, demonstrated their artistry inside the school on one side of the hall. On the other side, Indian boarding school students displayed their achievements in reading, writing, music, dancing, trades and arts.[51] The Carlisle Indian Band performed at the Pennsylvania state pavilion, and the Haskell Indian Band performed a mixture of classical, popular music and Wheelock’s “Aboriginal Suite” which included Native dances and war whoops by band members.[52]

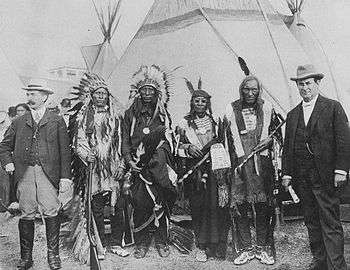

1905 inaugural parade of Theodore Roosevelt

On March 4, 1905, Wild Westers and Carlisle students portrayed contrasting images of Native Americans at the First Inaugural Parade of Theodore Roosevelt. Six famous Native American Chiefs, Geronimo (Apache), Quanah Parker (Comanche), Buckskin Charlie (Ute), American Horse (Oglala Lakota), Hollow Horn Bear (Sicangu Lakota) and Little Plume (Blackfeet), met in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, to rehearse the parade with the Carlisle Cadets and Band.[53] Theodore Roosevelt sat in the presidential box with his wife, daughter and other guests, and watched West Point cadets and the famed 7th Cavalry, Gen. George A. Custer’s former unit that fought at the Battle of Little Bighorn, march down Pennsylvania Avenue. When the contingent of Wild Westers and the Carlisle Cadets and Band came into view, President Roosevelt waved his hat and all in the President’s box rose to their feet to see the six famous Native American Chiefs adorned with face paint and elaborate feather headdresses, riding on horseback, followed by the 46-piece Carlisle Indian School Band and a brigade of 350 Carlisle Cadets at arms. Leading the group was Geronimo, in full Apache regalia, riding a horse also in war paint. It was reported that: “The Chiefs created a sensation, eclipsing the intended symbolism of a formation of 350 uniformed Carlisle students led by a marching band,” and “all eyes were on the six chiefs, the cadets received passing mention in the newspapers and nobody bothered to photograph them.”[54]

21st century Wild Westing

Wild Westers still perform in movies, pow-wows, pageants and rodeos. Some Oglala Lakota people carry on family show business traditions from Carlisle alumni who worked for Buffalo Bill and other Wild West shows.[55] Americans and Europeans continue to have a great interest in Native peoples and enjoy modern Pow-wow culture. First began in Wild West shows, Pow-wow culture is popular with Native American throughout the United States and a source of tribal enterprise. Americans and Europeans continue to enjoy traditional Native Americans skills; horse culture, ceremonial dancing and cooking; and buying Native American art, music and crafts. There are several on-going national projects that celebrate Wild Westers and Wild Westing.

The National Museum of American History's Photographic History Collection at the Smithsonian Institution preserves and displays Gertrude Käsebier's photographs, as well as many others by photographers who captured the displays of Wild Westing.

References

- ↑ See, E.H. Gohl, (Tyagohwens), “The Effect of Wild Westing”, The Quarterly Journal of the Society of American Indians, Washington, D.C., Volume 2, 1914, p.226-228. Heppler, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians”. Other major shows included Pawnee Bill, Cummins Wild West, Miller’s 101 Ranch and Sells-Floto Circus.

- ↑ Michele Delaney, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: A Photographic History by Gertrude Kasebier, Smithsonian National Museum of American History”, (hereinafter “Delaney”) (2007), p.21. “Wild West Shows and Images”, p.xiii.

- ↑ Jason A. Heppler, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians”, 2011. Buffalo Bill's Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians is a collaborative project of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Department of History with the assistance from the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

- ↑ See, E.H. Gohl, (Tyagohwens), “The Effect of Wild Westing”, The Quarterly Journal of the Society of American Indians, Washington, D.C., Volume 2, 1914, p.226-228.

- ↑ Chauncey Yellow Robe, “The Menace of the Wild West Show”, The Quarterly Journal of the Society of American Indians, Washington, D.C., Volume 2, p.224-225.

- ↑ "It was one thing to portray docile natives who had not progressed much since the late fifteenth century, but quite another matter to portray some of them as armed and dangerous.” L.G. Moses, “Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933, (hereinafter “Wild West Shows and Images”) (1996), p.133.

- ↑ Commissioner John H. Oberly explained in 1889: "The effect of traveling all over the country among, and associated with, the class of people usually accompanying shows, circuses and exhibitions, attended by all the immoral and unchristianizing surroundings incident to such a life, is not only most demoralizing to the present and future welfare of the Indian, but it creates a roaming and unsettled disposition and educates him in a manner entirely foreign and antagonistic to that which has been and now is the policy of the Government.

- ↑ Wild West Shows and Images”, p. 275

- ↑ “Wild West Shows and Images”, pp.137-138.

- ↑ Alida S. Boorn, “Oskate Wicasa (One Who Performs)” (hereinafter “Oskate Wicasa”), Central Missouri State University, (2005), p. 47

- ↑ Chief Geronimo was an entrepreneur, cutting off his suit buttons as he walked the fairgrounds and selling them as celebrity souvenirs. He also made souvenir bows, arrows and canes; and signed photographs for twenty-five cents. Parezo, Nancy J. and Fowler, Don D, “The 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition: Anthropology Goes to the Fair”, (2007), p.113.

- ↑ Heppler, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians”. Other major shows included Pawnee Bill, Cummins Wild West, Miller’s 101 Ranch and Sells-Floto Circus.

- ↑ Michele Delaney, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: A Photographic History by Gertrude Kasebier, Smithsonian National Museum of American History”, (hereinafter “Delaney”) (2007), p.21. “Wild West Shows and Images”, p.xiii.

- ↑ Calls the Name and other women supplemented wages by making and selling Lakota crafts. Women served important community roles in camps backstage. Augmenting their show wages was common among Show Indians, especially "'bead work' made into moccasins, purses, etc.," which earned them "very large prices," according to Nate Salsbury. Cody and Salsbury often purchased goods at wholesale prices and sold the goods to Indians at cost, allowing them to create souvenirs for tourists. Show Indians created and sold goods to museums, collectors, and customers across Europe and the United States. Heppler, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians”. Performers’ newborn babies became part of the villages set up outside show areas. Oskate Wicasa, p.164.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.6, 54. The number of police chosen depended on the number of Indians traveling with the show each season, a usual number being one policeman for every dozen Indians. Indian policemen, selected from the ranks of the performers, were given badges and paid $10 more in wages per month. in 1898, Chief Iron Tail managed the Indian Police. Delaney, p. 32.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.3.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.2.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.47.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.5.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.3.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.60.

- ↑ However, travel was occasionally hazardous and there were accidents and misadventures. Oskate Wicasa, p.6. Was injured the next year in a train accident and almost died. Luther Standing Bear was severely injured in a train accident and almost died. Luther Standing Bear, “My People the Sioux”, (1928), p. 256.

- ↑ Chief Iron Tail was an international personality and appeared as the lead with Buffalo Bill at the Champs- Élysées in Paris, France, and the Colosseum in Rome, Italy. In France, as in England, Buffalo Bill and Iron Tail were feted by the aristocracy. Early in the twentieth century, Iron Tail's distinctive profile became well known across the United States as one of three models for the five-cent coin Buffalo nickel or Indian Head nickel. The popular coin was introduced in 1913 and showcases the native beauty of the American West.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.67.

- ↑ L.G. Moses, "Indians on the Midway: Wild West Shows and the Indian Bureau at World's Fairs, 1893-1904", (hereinafter "Indians on the Midway"), South Dakota State Historical Society, p. 207.

- ↑ Linda F. Witmer, “The Indian Industrial School: Carlisle, Pennsylvania 1879-1918, Cumberland County Historical Society (2002), cover.

- ↑ The total number of students is listed as 10,595, with 1,842 list of names and nation unknown. Carlisle Indian School Tribal Enrollment Tally (1879-1918). http://home.epix.net/~landis/tally.html

- ↑ Robert M. Utlely, ed. “Battlefield & Classroom: An Autobiography by Richard Henry Pratt”, (hereinafter “Utely”) (1964), p. xi-xvi.

- ↑ See Carlisle Indian School Yearly Results, http://www.cfbdatawarehouse.com/data/discontinued/c/carlisle/yearly_results.php?year=1910

- ↑ Witmer, p.xvi. Carlisle had developed something of a rivalry with Harvard, and though the Indians had never beaten the Crimson, they always gave them a game. The Indians both admired and resented the Crimson, in equal amounts. They loved to sarcastically mimic the Harvard accent; even players who could barely speak English would drawl the broad Harvard a. But Harvard was also the Indians' idea of collegiate perfection, and they labeled any excellent performance, whether on the field or in the classroom, as "Harvard style." Sally Jenkins, “The Real All Americans”, (2007).

- ↑ Tom Benjey, “Doctors, Lawyers, Indian Chiefs”, (2008).

- ↑ Delaney, p.21. “Wild West Shows and Images”, p.xiii.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa is a colloquialism meaning “one who performs.” Its usage began in the early days of the Buffalo Bill Cody Wild West Shows. Oskate Wicasa, p.1. The phrase "Show Indians" likely originated among newspaper reporters and editorial writers as early as 1891. By 1893 the term appears frequently in Bureau of Indian Affairs correspondence. Some believe that the term is derogatory, describing the "phenomenon of Native exploitation and romanticization in the U.S." Arguments of a similar nature were made by the Bureau of Indian Affairs during the popularity of Wild West shows in the U.S. and Europe. “Indians on the Midway”, p. 219

- ↑ Heppler, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Progressive Image of American Indians”.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.164.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.6.

- ↑ Witmer, p.xv. Oskate Wicasa, p.101-103.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.8.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.101-103.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.131.

- ↑ Ann Rinaldi, “My Heart is on the Ground: the Diary of Nannie Little Rose, a Sioux Girl, Carlisle Indian School, Pennsylvania, 1880,” (1999), p. 177.

- ↑ Joseph Agonito, “Lakota Portraits: Lives of the Legendary Plains People” (hereinafter “Agonito”)(2011), p.237.

- ↑ David R.M. Beck, “The Myth of the Vanishing Race”, Associate Professor, Native American Studies, University of Montana, February, 200. “Wild West Shows and Images”, p.131, 140.

- ↑ “Wild West Shows and Images”, p.131, 140.

- ↑ Financial difficulties, however, led the Bureau of Indian Affairs to withdraw its sponsorship and left the ethnological Indian Villages exhibit under the directorship of Frederick W. Putnam of Harvard's Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Robert A. Trennert, Jr., "Selling Indian Education at World's Fairs

- ↑ "Indians on the Midway”, p. 210-215.

- ↑ Parezo and Fowler, p.6. “Wild West Shows and Images”, p.137-138.

- ↑ Parezo and Fowler, p.6.

- ↑ Indians performing included Oglala Lakotas from Pine Ridge Reservation with Cummins’s Wild West Show and Brule Lakotas from Rosebud Reservation with the Department of Anthropology. Parezo and Fowler, p.131.

- ↑ Parezo and Fowler, p.134.

- ↑ Parezo and Fowler, p. 135-136. 354, 459. J. McGee portrayed contrasting images of Native Americans and was critical of BIA programs destroying Native cultures and turning Indians into “counterfeit Caucasians.”

- ↑ Parezo and Fowler, p.156.

- ↑ A week or so before the inauguration, six famous chiefs from formerly hostile tribes, arrived in Carlisle to head the school’s contingent in the parade. But, before they left for Washington, there was much to do. First, they spoke to an assembly of students through interpreters. A dress rehearsal was held on the main street of Carlisle to practice for the parade. The Carlisle Herald predicted that the group would be one of the big parade’s star attractions. Those marching in the parade were woken at 3:45 a.m., had breakfast at 4:30, and were the special train to Washington at 5:30. As the train rolled out of Carlisle, a heavy snow fell, but later the sun burned through, making for a fine day weather-wise. Fortunately, the travelers had lunch on the train because it was late in arriving in Washington. They were hurried into the last division of the Military Grand Division. Originally, they were to have been in the Civic Grand Division, but Gen. Chaffee transferred all cadets under arms to the military division, putting them in a separate brigade. Tom Benjey, “Carlisle Indian School”, 1905 Inaugural Parade, (2009).

- ↑ Robert M. Utely, “Geronimo” p.257, 2012; The Carlisle Band were led by Claude M. Stauffer and cadets led by Captain William M. Mercer, superintendent of the school and member of the 7th Cavalry. Tom Benjey, “Carlisle Indian School”, 1905 Inaugural Parade, (2009). Witmer, p. 26.

- ↑ Oskate Wicasa, p.121.

Further reading

- Michelle Delaney, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Warriors: Photographs by Gertrude Käsebier”, Smithsonian Institution