Waterfalls in Ricketts Glen State Park

There are 24 named waterfalls in Ricketts Glen State Park in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania along Kitchen Creek as it flows in three steep, narrow valleys, or glens. They range in height from 9 feet (2.7 m) to the 94-foot (29 m) Ganoga Falls. Ricketts Glen State Park is named for R. Bruce Ricketts, a colonel in the American Civil War who owned over 80,000 acres (32,000 ha) in the area in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but spared the old-growth forests in the glens from clearcutting. The park, which opened in 1944, is administered by the Bureau of State Parks of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR). Nearly all of the waterfalls are visible from the Falls Trail, which Ricketts had built from 1889 to 1893 and which the state park rebuilt in the 1940s and late 1990s. The Falls Trail has been called "the most magnificent hike in the state" and one of "the top hikes in the East".[1]

The waterfalls are on the section of Kitchen Creek that flows down the Allegheny Front, a steep escarpment between the Allegheny Plateau to the north and the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians to the south. The glens are made of sedimentary rocks from the Huntley Mountain and Catskill Formations that formed up to 370 million years ago in the Devonian and Carboniferous periods. The waterfalls are the result of increased flow in Kitchen Creek from glaciers enlarging its drainage basin during the last Ice Age.

Ricketts named 21 of the waterfalls, mostly for Native American tribes and places, and his family and friends. There are ten named falls in Ganoga Glen, eight named falls in Glen Leigh, and between four and six named waterfalls in Ricketts Glen. The DCNR names 22 falls, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) names 23 falls, and Scott E. Brown's 2004 book Pennsylvania waterfalls: a guide for hikers and photographers names 24. The falls are described in order going upstream along the creek for each of the three glens.

Geology

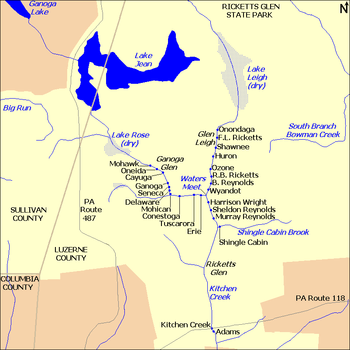

The waterfalls in Ricketts Glen State Park are on the Allegheny Front, which is the boundary between the Allegheny Plateau to the north and the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians to the south. The headwaters of Kitchen Creek are on the dissected plateau, from which the stream drops approximately 1,000 feet (300 m) in 2.25 miles (3.62 km) as it flows down the steep escarpment of the Allegheny Front. Much of this drop occurs in Glen Leigh and Ganoga Glen, two narrow valleys carved by branches of Kitchen Creek, which come together at Waters Meet.[2][a] The branch in Glen Leigh has eight named waterfalls and lies north of the confluence, while the branch in Ganoga Glen has ten named waterfalls and lies to the northwest. Ricketts Glen lies south of and downstream from Waters Meet; here the terrain becomes less steep, and there are fewer named waterfalls. The DCNR names only four in Ricketts Glen, all on Kitchen Creek;[3] the USGS GNIS names these and one more on the creek,[4] and Brown's book on Pennsylvania waterfalls adds a sixth named falls on a tributary.[5]

The rocks exposed in the park were formed between 370 and 340 million years ago, when the land was part of the coastline of a shallow sea that covered a great portion of what is now North America. The high mountains to the east of the sea gradually eroded, causing a build-up of sediment made up primarily of clay, sand and gravel. Tremendous pressure on the sediment caused the formation of the rocks that are found in the park and in the Kitchen Creek drainage basin: sandstone, shale, siltstone, and conglomerates.[2]

About 300 to 250 million years ago, the Allegheny Plateau, Allegheny Front, and Appalachian Mountains all formed in the Alleghanian orogeny. This happened long after the sedimentary rocks in the park were deposited, when the part of Gondwana that became Africa collided with what became North America, forming Pangaea. In the years since, up to 5,000 feet (1,500 m) of rock has been eroded away by streams and weather. At least three major glaciations in the past million years have been the final factor in shaping the land that makes up the park today.[2][6][7]

The effects of glaciation have made Kitchen Creek "unique compared to all other nearby streams that flow down the Allegheny Front", as it is the only one with an "almost continuous series of waterfalls".[2] Prior to the last ice age, Kitchen Creek and Phillips Creek to the east had drainage basins of similar area and slope, and both watersheds were confined to the Allegheny Front. This changed when receding glaciers formed temporary dams on two of Kitchen Creek's neighboring streams on the Allegheny Plateau, South Branch Bowman Creek to the northeast and Big Run, a tributary of Fishing Creek to the northwest. The headwaters of South Branch Bowman Creek were very close to those for the Glen Leigh branch of Kitchen Creek, and the headwaters for Big Run were very close to those for the Ganoga Glen branch.[2]

As the glaciers retreated to the northeast about 20,000 years ago, glacial lakes formed. Drainage from the melting glacier and lakes cut a sluiceway, or channel, that diverted the headwaters of South Branch Bowman Creek into the Glen Leigh branch of Kitchen Creek. The retreating glaciers also left deposits of debris 20 to 30 feet (6.1 to 9.1 m) thick, which formed a dam blocking water from draining into Big Run. Instead water from Ganoga Lake and the area that later became Lake Jean was diverted into the Ganoga Glen branch of Kitchen Creek. These diversions added about 7 square miles (18 km²) to the Kitchen Creek drainage basin, increasing it by just over 50 percent to 20.1 square miles (52 km²).[2][8]

The result was increased water flow in Kitchen Creek, which has been cutting the falls in the glens since. The gradient or slope of Kitchen Creek was fairly stable for its flow when it had a much smaller drainage basin, as Phillips Creek still does. The increased basin size means that Kitchen Creek in the glens is too steep for its present amount of water flow. As Kitchen Creek continues to cut into the rock and erode it up the Allegheny Front, the creek's slope will decrease and become less steep. In the future, the creek's flow and slope are predicted to become similar to those of other nearby creeks with similar size drainage basins. This process could take so long that a new glacial period might occur before the transformation is complete.[2]

Formations and falls

The park's waterfalls expose two distinct rock formations from the Devonian and Carboniferous periods. The higher and more recent of these is the Huntley Mountain Formation, from the late Devonian and early Mississippian. This is made of layers of olive green to gray sandstone and gray to red shale. The lower and older layer is the Catskill Formation, which is composed of red shale and siltstone up to 370 million years old. The harder Huntley Mountain Formation caps the Allegheny Front and has kept it from eroding as much as the softer Catskill Formation to the south. The portions of the Allegheny Front within the park are named North Mountain and Red Rock Mountain, with the latter name coming from an exposed band of Huntley Formation red shale and sandstone visible along Pennsylvania Route 487.[2][6][9][10]

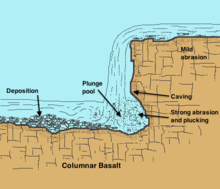

Geologists classify the falls at Ricketts Glen State Park into two types. Wedding-cake falls descend in a series of small steps, forming waterfalls that are said to resemble a wedding cake. Within the park, this type of falls usually flows over thin layers of Huntley Mountain Formation sandstone. In bridal-veil falls, the second type, water falls over a ledge and drops vertically into a plunge pool in the stream bed below. Within the park, this type of falls flows over Catskill Formation rocks or the red shale and sandstone of the Huntley Formation. In the park, the harder caprock which forms the ledge from which the bridal-veil falls drops is grey sandstone. The softer red shale below is eroded away by water, sand and gravel to form the plunge pool.[2]

While the official Ricketts Glen State Park web page also classifies waterfalls as either the bridal-veil or wedding-cake type,[11] Brown's Pennsylvania waterfalls: a guide for hikers and photographers uses four types for classification: falls, cascade, slide, and chute. The first, falls, is the same as the DCNR's bridal-veil type, with water that falls freely from a ledge. Brown divides the wedding-cake class into three types: cascade, where water falls down a "vertical to nearly vertical" surface that has terraces; slide, where water falls down a "near vertical to less than vertical" wide surface that is smoother than a cascade; and chute, where the water is confined by rock as it falls down "a narrow slide or cataractlike feature".[12]

History

Ricketts Glen State Park is in the Susquehanna River drainage basin, the earliest recorded inhabitants of which were the Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannocks. Their numbers were greatly reduced by disease and warfare with the Five Nations of the Iroquois, and by 1675 they had died out, moved away, or been assimilated into other tribes. After this, the lands of the Susquehanna valley were under the nominal control of the Iroquois, who encouraged displaced tribes from the east to settle there, including the Shawnee and Lenape (or Delaware).[13]

On November 5, 1768, the British acquired land, known in Pennsylvania as the New Purchase, from the Iroquois in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix; this included what is now Ricketts Glen State Park.[14] After the American Revolutionary War, Native Americans almost entirely left Pennsylvania.[15] Luzerne County was formed in 1786 from part of Northumberland County, and Fairmount Township, where the waterfalls are, was settled in 1792 and incorporated in 1834.[16] About 1890 a Native American pot, decorated in the style of "the peoples of the Susquehanna region", was found under a rock ledge on Kitchen Creek by Murray Reynolds, for whom a waterfall is named.[17]

The Ricketts family began acquiring land in and around what became the park in 1851, when Elijah Ricketts and his brother Clemuel bought about 5,000 acres (2,000 ha) on North Mountain around what is now known as Ganoga Lake. By 1852 they had built a stone house on the lake shore, which they ran "as a lodge and tavern".[18][19] Elijah's son Robert Bruce Ricketts, for whom the park is named, joined the Union Army as a private at the outbreak of the American Civil War and rose through the ranks to become a colonel. After the war, R. B. Ricketts returned to Pennsylvania and began purchasing the land around the lake from his father in 1869; eventually he controlled or owned more than 80,000 acres (32,000 ha), including the glens and waterfalls.[11][19]

Ricketts and the other settlers living in the area were not aware of the glens and their waterfalls until about 1865, when they were discovered by two of the Ricketts' guests who went fishing and wandered down Kitchen Creek. In 1872 Ricketts built a three-story wooden addition to the stone house; this opened as the North Mountain House hotel in 1873, and was run by Ricketts' brother Frank until 1898.[18][20]

Ricketts named 21 of the waterfalls; most have Native American names, and others are named for relatives and friends.[21] In 1879 Ricketts started the North Mountain Fishing Club,[20] and he renamed Long Pond as Ganoga Lake in 1881, based on a suggestion by Pennsylvania senator Charles R. Buckalew. Ricketts also used the name Ganoga for the tallest waterfall and the glen it flows through. In 1889 Ricketts hired Matt Hirlinger and five other men to build the trails along Kitchen Creek. It took them four years to complete the trails and stone steps through the glens.[21] The wooden addition to the stone house was torn down in 1897, and the hotel and fishing club closed in 1903; the stone house remained the Ricketts' summer home.[18][20]

Ricketts was a lumberman who made his fortune clearcutting nearly all his land, but the glens were "saved from the lumberman's axe through the foresight of the Ricketts family".[22] Ricketts died in 1918; between 1920 and 1924 the Pennsylvania Game Commission bought 48,000 acres (19,000 ha) from his heirs, via the Central Pennsylvania Lumber Company. This became most of Pennsylvania State Game Lands Number 13, west of the park in Sullivan County.[23] These sales left the Ricketts heirs with over 12,000 acres (4,900 ha) surrounding Ganoga Lake, Lake Jean and the glens. The area was approved as a national park site in the 1930s,[11] and the National Park Service planned a Civilian Conservation Corps camp at "Ricketts Glynn" (sic).[24][25] Budget problems and World War II brought an end to national plans for development.[11][26]

In 1942 the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania bought 1,261 acres (510 ha), including the glens and their waterfalls, from the heirs for $82,000. Ricketts Glen State Park opened in 1944. The state bought a total of 16,000 acres (6,500 ha) more from the heirs in 1945 and 1950 for $68,000; the park today has about 10,000 acres (4,000 ha) from the Ricketts family and about 3,000 acres (1,200 ha) acquired from others.[11][23] A 1947 newspaper article estimated that the new park would have 50,000 visitors that year, and detailed the work the state had done since acquiring the land. The Falls Trail through the glens was rebuilt, all the stone steps were replaced, and signs were added. Out of concern for greater safety, footbridges with handrails replaced those made from hewn logs, overhanging rock ledges were removed in places, and the trail was rerouted near some falls. The Evergreen Trail past Adams Falls was built at this time.[22]

In 1969 the Glens Natural Area was named a National Natural Landmark, and it became a Pennsylvania State Park Natural Area in 1993, which guarantees it "will be protected and maintained in a natural state".[11] In 1996 heavy rains washed out two bridges on the Falls Trail; because of the difficulty of transporting materials on the trail, an Army National Guard helicopter dropped 36-foot (11 m) poles into the glens to rebuild the bridges in early 1997.[27] In the winter of 1997 ice climbing was allowed in the Ganoga Glen section of the park for the first time.[28] That same year local fire companies trained to rescue people injured in the park when icy conditions make reaching and transporting them treacherous.[29] In 1998 a four-year project to "repair and improve the Falls Trail" began, with three park employees carrying materials in on foot to stabilize the trail, fix steps, reduce erosion, and repair some bridges.[30] In 2001, John Young in Hike Pennsylvania: An Atlas of Pennsylvania's Greatest Hiking Adventures wrote of the Falls Trail: "This is not only the most magnificent hike in the state, but it ranks up there with the top hikes in the East."[1] The readers of Backpacker magazine chose the Falls Trail as the best hike in Pennsylvania in 2009, and as one of the best hikes in the Northeast in 2010.[31][32]

Overview

Kitchen Creek flows through the park's three glens, which the descriptions of the waterfalls are organized by: Ricketts Glen, Glen Leigh, and Ganoga Glen. The falls are listed in order going upstream along Kitchen Creek, starting with the southernmost and ending at the northernmost in each glen. This is also the order in which a hiker would encounter the falls while traveling north along the creek on the Falls Trail.[3]

The Falls Trail is a 7.1-mile (11.4 km) loop hike. Starting at PA 118, it is 1.8 miles (2.9 km) north along the creek through Ricketts Glen to Waters Meet, where the trail divides. Following the Glen Leigh branch, it is 1.2 miles (1.9 km) north through the glen to the Highland Trail, then 1.0 mile (1.6 km) west along the Highland Trail to Ganoga Glen. Turning southeast, it is 1.3 miles (2.1 km) through Ganoga Glen back to Waters Meet, then the 1.8 miles (2.9 km) through Ricketts Glen is retraced, but heading south back to PA 118.[33]

The description of each waterfall starts with the name. While the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR) Bureau of State Parks names 22 waterfalls in Ricketts Glen State Park (all but Kitchen Creek and Shingle Cabin),[3] the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) names 23 (all but Shingle Cabin),[34] and Scott E. Brown's 2004 book Pennsylvania waterfalls: a guide for hikers and photographers names 24.[5] There are also several unnamed waterfalls in the park, with the total number of falls given as 33 or 34.[35][36][37] For each waterfall the height is given next, followed by the elevation above sea level, and the latitude and longitude.[3][5][38] Each waterfall in the table is classified according to the four types used in Brown's book (falls, cascade, slide, and chute), with some classified as combinations of types.[5] For each waterfall there are notes, which can give more information on the waterfall, the etymology of the name, and the location on the Falls Trail, followed by a photograph.

Ricketts Glen

Ricketts Glen is the name given to the Kitchen Creek valley south and downstream of Waters Meet.[5][11][39] It is 1.8 miles (2.9 km) between Pennsylvania Route 118 and Waters Meet on the Falls Trail, making this the longest glen. The three northernmost waterfalls are all within 0.5 miles (0.80 km) of Waters Meet, and are only a short hike from the bottom of Ganoga Glen or Glen Leigh. The southern part of this glen has large areas of old-growth forest, chiefly hemlocks.[40] Ricketts Glen is entirely in the Catskill Formation and all of the falls on this section of Kitchen Creek have plunge pools.[2]

Ricketts Glen is the only glen where sources differ on the number of named waterfalls. Only Brown's book names Shingle Cabin Falls, which is the sole named falls in the park on a tributary of Kitchen Creek.[40] The names of the waterfalls at the southern end of Ricketts Glen, under and just south of PA 118, are the most disputed. The USGS GNIS names Kitchen Creek Falls (with coordinates very near the PA 118 bridge) and Adams Falls (with coordinates further south of PA 118).[4][41] Brown's book also names both as separate falls and gives the height of Kitchen Creek Falls as 9 feet (2.7 m).[5] A 1947 newspaper article on the new state park notes the unnamed falls under the highway bridge and refers to "Adam's Falls a short distance away".[22] The official park map only names Adams Falls, shows it a short distance south of the bridge, and notes it is 36 feet (11 m) tall.[3] However, the DCNR Pennsylvania Trail of Geology guide to the park says Kitchen Creek Falls is just another name for Adams Falls, and notes that "At the bridge on Pa. Route 118, Kitchen Creek plunges over three picturesque cascades (18, 25 and 10 feet high)" (5.5, 7.6, and 3.0 m high).[2]

| Name[3] | Height[3][42] | Elevation[34] | Coordinates[34] | Type[5] | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams | 36 feet (11.0 m) | 1,214 feet (370 m)[41] | 41°17′54″N 76°16′23″W / 41.29833°N 76.27306°W | chute |  |

| Adam Kale was a watchman on Kitchen Creek employed by the North Mountain Fishing Club,[43][44] and the waterfall's name was still spelled "Adam's Falls" in 1947.[22] Adams Falls, according to the DCNR Pennsylvania Trail of Geology guide, "is the most beautiful and the most accessible falls in the park".[2] It is the only named waterfall in the park south of Pennsylvania Route 118 and the only one not visible from the Falls Trail; it is a short distance from the parking lot on the 1-mile (1.6 km) Evergreen Trail.[3] Adams Falls has carved a narrow chute in the rock,[45] and its lower plunge pool, Leavenworth Pool, has a diameter of 30 feet (9.1 m) and a depth of 8 to 10 feet (2.4 to 3.0 m).[2] The pool is named for Frank Leavenworth, from Wilkes-Barre who operated coal mines and served as president of the fishing club.[43][44] | |||||

| Kitchen Creek | 9 feet (2.7 m) | 1,234 feet (376 m)[4] | 41°17′57″N 76°16′26″W / 41.29917°N 76.27389°W | falls |  |

| Kitchen Creek Falls is directly under the Pennsylvania Route 118 (PA 118) bridge, and has carved a narrow chute no more than 3 feet (0.91 m) wide in the rock.[45][46] According to Brown, it is the shortest named waterfall in the park at 9 feet (2.7 m), but according to the Pennsylvania Trail of Geology it is 18 feet (5.5 m) tall.[2][5] Although Kitchen Creek Falls is visible from the Falls Trail, it is not one of the DCNR's 22 named waterfalls. It is named in the USGS GNIS and Brown's book.[4][5] | |||||

| Shingle Cabin | 25 feet (7.6 m) | 1,378 feet (420 m)[47] | 41°18′56″N 76°16′23″W / 41.31556°N 76.27306°W | cascade |  |

| Shingle Cabin Falls is on Shingle Cabin Brook, which enters the left bank of Kitchen Creek downstream of Murray Reynolds Falls. The Falls Trail is on the right bank, the opposite side of the creek from the falls, and foliage obscures the view much of the year. It is not one of the DCNR's 22 named waterfalls, but is named in Brown's book.[5] | |||||

| Murray Reynolds | 16 feet (4.9 m) | 1,447 feet (441 m)[48] | 41°19′06″N 76°16′26″W / 41.31833°N 76.27389°W | chute |  |

| G. Murray Reynolds (1838–1904) was a colonel, politician, and a brother of Elizabeth Reynolds Ricketts, wife of R. B. Ricketts.[49] Murray Reynolds Falls was once known as "Pulpit Falls" for the pulpit-shaped rock in the midst of the chute.[46] It is 1.3 miles (2.1 km) north of PA 118, 0.5 miles (0.80 km) south of Waters Meet, and is the first of the falls named by the DCNR encountered when heading north on the Falls Trail.[40] | |||||

| Sheldon Reynolds | 36 feet (11.0 m) | 1,476 feet (450 m)[50] | 41°19′09″N 76°16′28″W / 41.31917°N 76.27444°W | falls, then cascade |  |

| Sheldon Reynolds (1845–1895) was a lawyer, banker, historian, and a brother of Elizabeth Reynolds Ricketts, wife of R. B. Ricketts.[51] Sheldon Reynolds Falls is 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north of PA 118 and 0.3 miles (0.48 km) south of Waters Meet. As hikers approach Sheldon Reynolds Falls from the south, Harrison Wright Falls is visible above it in the distance.[40][46] | |||||

| Harrison Wright | 27 feet (8.2 m) | 1,519 feet (463 m)[52] | 41°19′14″N 76°16′31″W / 41.32056°N 76.27528°W | falls |  |

| Harrison Wright (1850–1885) was a lawyer with a doctorate in mineralogy and an interest in archeology. He was active in the Wyoming Historical and Geological Society with R. Bruce Ricketts.[53][54] Harrison Wright Falls is "perhaps the most photogenic falls in the park",[45] and is 1.6 miles (2.6 km) north of PA 118 and 0.2 miles (0.32 km) south and downstream of Waters Meet.[40] | |||||

Glen Leigh

Marcia Bonta in Outbound Journeys in Pennsylvania: A Guide to Natural Places for Individual and Group Outings calls this "the loveliest part of the entire trail—rugged, steep Glen Leigh". Bonta goes on to note that Glen Leigh "resembles a remote wilderness, hemmed in on one side by rock and on the other by surging water, and it has some of the most spectacular waterfalls in the park".[55]

Glen Leigh was named for Lake Leigh, which R. B. Ricketts named for his second daughter Frances Leigh (1881–1970). She married William S. McLean, Jr., a judge, in 1921.[23][43][44] Leigh was also the middle name of R.B. Ricketts' mother, Margaret Leigh Lockart Ricketts (1810–1891).[56] In 1907, R. B. Ricketts built a dam upstream of the waterfalls on the Glen Leigh branch of Kitchen Creek, hoping to use the resulting Lake Leigh for hydroelectric power generation. The dam was "poorly constructed" and could not be used to generate power; it was condemned by the state and the lake drained in 1956.[56][57] Almost all of Glen Leigh is in the Huntley Mountain Formation, but a small region at the southern end, including Waters Meet, is in the Catskill Formation.[2]

Glen Leigh has eight named waterfalls in 0.64 miles (1.03 km). It is 1.8 miles (2.9 km) from PA 118 in the south to Waters Meet and the southern end of Glen Leigh. The glen is also accessible from the north; it is 1.04 miles (1.67 km) from the Lake Leigh trailhead parking lot by Lake Jean to Onondaga, the northernmost waterfall.[45] The Highland Trail is the 1.2-mile (1.9 km) path between the northern ends of Glen Leigh and Ganoga Glen. It meets the Falls Trail just north of Onondaga Falls and has a short connector to F. L. Ricketts, the next waterfall south.[3] The Falls Trail by both of these northernmost waterfalls had to be rebuilt in the early 2000s.[40][46]

| Name[3] | Height[3] | Elevation[34] | Coordinates[34] | Type[5] | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wyandot | 15 feet (4.6 m) | 1,608 feet (490 m)[58] | 41°19′20″N 76°16′29″W / 41.32222°N 76.27472°W | falls |  |

| Wyandot Falls is one of two named waterfalls visible from Waters Meet (Erie Falls in Ganoga Glen is the other). It is the first named falls in Glen Leigh, and is 0.09 miles (0.14 km) upstream of Waters Meet.[45] The Wyandots are an Iroquoian-speaking people (also known as the Hurons) who once lived in modern day Ontario; they were decimated by disease, then defeated by the Iroquois by 1649. The people who call themselves Wyandots now live in Oklahoma.[59] | |||||

| B. Reynolds | 40 feet (12.2 m) | 1,637 feet (508 m)[60] | 41°19′24″N 76°16′29″W / 41.32333°N 76.27472°W | falls |  |

| Benjamin Reynolds (1840–1913) was a banker and a brother of Elizabeth Reynolds Ricketts, wife of R. B. Ricketts; the Reynolds and Ricketts families shared a double house in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.[61] B. Reynolds Falls is between 0.1 and 0.2 miles (0.16 and 0.32 km) upstream of Waters Meet, and is the second named falls in Glen Leigh. When the water is low it is only a "horse tail" falls.[45] | |||||

| R. B. Ricketts | 36 feet (11.0 m) | 1,676 feet (510 m)[62] | 41°19′27″N 76°16′27″W / 41.32417°N 76.27417°W | cascade, then cascade |  |

| Robert Bruce Ricketts (1839–1918) was a colonel in the Union Army in the American Civil War who fought at Gettysburg. He owned more than 80,000 acres (32,000 ha) at one time and sold most of its lumber. Ricketts did preserve the old-growth forest in what became Ricketts Glen State Park, which is named for him. Ricketts named 21 waterfalls on Kitchen Creek and hired six workers to build the original Falls Trail from 1889 to 1893.[11][63] The "exceedingly pleasant" R. B. Ricketts Falls is 0.24 miles (0.39 km) upstream of Waters Meet, and is the third named falls in Glen Leigh.[45] | |||||

| Ozone | 60 feet (18.3 m) | 1,752 feet (534 m)[64] | 41°19′32″N 76°16′29″W / 41.32556°N 76.27472°W | cascade |  |

| Named for the Ozone hiking club of Wilkes-Barre, which used the Ricketts house on the mountain as a local base.[43][44] Although the reason for the club's choice of name is unknown, the only other Ozone Falls in the United States was so named because the air near the falls was believed to have a "stimulating quality" from the waterfall's mist.[65][66] Ozone Falls is the tallest in Glen Leigh at 60 feet (18 m) and second tallest in the park. It is 0.35 miles (0.56 km) upstream of Waters Meet, and is the fourth named falls in Glen Leigh.[45] The Falls Trail climbs a switchback beside the falls, and crosses Kitchen Creek just above it on a bridge. Water can cover the trail here.[46] | |||||

| Huron | 41 feet (12.5 m) | 1,795 feet (547 m)[67] | 41°19′36″N 76°16′27″W / 41.32667°N 76.27417°W | slide |  |

| Huron Falls has a 90-degree turn as it slides down sandstone from the Huntley Mountain Formation. It is about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) upstream of Waters Meet, and is the fifth named falls in Glen Leigh. The top of Huron is just below the plunge pool of Shawnee Falls; Brown speculates that Huron and Shawnee Falls were once one waterfall.[45] The Hurons are an Iroquoian-speaking people (also known as the Wyandots) who once lived in modern day Ontario; they were decimated by disease, then defeated by the Iroquois by 1649. The people who call themselves Hurons now live in Quebec.[59] | |||||

| Shawnee | 30 feet (9.1 m) | 1,880 feet (570 m)[68] | 41°19′40″N 76°16′26″W / 41.32778°N 76.27389°W | falls, then falls |  |

| Shawnee Falls is 0.51 miles (0.82 km) upstream of Waters Meet, and is the sixth named falls in Glen Leigh.[45] Shawnee and Huron falls are carving "a massive overhanging cliff of fractured sandstone" on the creek's left bank, opposite the trail;[46] Brown speculates that Shawnee and Huron Falls were once one waterfall.[45] The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking people who came to Pennsylvania as refugees in the late 17th century and left by 1772.[69][70] | |||||

| F. L. Ricketts | 38 feet (11.6 m) | 1,988 feet (606 m)[71] | 41°19′46″N 76°16′26″W / 41.32944°N 76.27389°W | slide |  |

| Frank L. Ricketts (1843–1908) was R. B. Ricketts younger brother and managed the Ricketts' North Mountain House hotel from 1873 to 1898. Frank was deaf from scarlet fever in his childhood.[20][43][72] F. L. Ricketts Falls is 0.63 miles (1.01 km) upstream of Waters Meet, and is the seventh named falls in Glen Leigh.[45] The trail was moved from the left bank, close to the falls, to the right bank of Kitchen Creek before 2003, as the wooden steps were too wet and unstable on the left side.[46] | |||||

| Onondaga | 15 feet (4.6 m) | 2,077 feet (633 m)[73] | 41°19′52″N 76°16′26″W / 41.33111°N 76.27389°W | cascade |  |

| Onondaga Falls is 0.73 miles (1.17 km) upstream of Waters Meet, and is the eighth and last named falls in Glen Leigh. It is 1.04 miles (1.67 km) south of the Lake Leigh trailhead parking lot by Lake Jean.[45] The trail to Onondaga Falls had to be reconstructed prior to 2001, after a storm washed it out.[40] The Onondaga are an Iroquoian-speaking people and one of the original members of the Iroquois Confederation. They were geographically in the middle of the five tribes and "tended the council fire" of the Iroquois Longhouse; as such they were one of three "Elder Brothers" in the Confederacy.[74] Their village at Onondaga, New York, was the Iroquois capital.[75] | |||||

Ganoga Glen

By 1875 Ricketts had named the tallest waterfall on Kitchen Creek Ganoga Falls,[76] and in 1881, he renamed Long Pond as Ganoga Lake. Pennsylvania senator Charles R. Buckalew suggested the name Ganoga, an Iroquoian word which he said meant "water on the mountain" in the Seneca language.[77] Donehoo's A History of the Indian Villages and Place Names in Pennsylvania identifies it as a Cayuga language word meaning "place of floating oil" and the name of a Cayuga village in New York.[78] Whatever the meaning, Ganoga Lake is the source of the branch of Kitchen Creek that flows through Ganoga Glen, which has the tallest waterfall.[3]

A dam was built upstream of the waterfalls on the Ganoga Glen branch of Kitchen Creek in 1842. Ricketts strengthened the dam circa 1905 as part of a hydroelectric power generation scheme, and renamed the body of water Lake Rose (Rose is a Ricketts family name). However, both the Lake Rose and Lake Leigh dams were "poorly constructed" and could not be used to generate power; both dams were condemned by the state and Lake Rose was drained in 1969.[56][57] Ganoga Glen is not as steep as Glen Leigh; both glens are almost entirely in the Huntley Mountain Formation, with a small region at the southern end, including Waters Meet, in the Catskill Formation.[2] Ganoga Glen has ten named waterfalls in 1.1 miles (1.8 km). It is 1.8 miles (2.9 km) from PA 118 in the south to Waters Meet and the southern end of Ganoga Glen. From the north, it is 0.3 miles (0.48 km) from the Lake Rose trailhead parking lot by Lake Jean to Mohawk, the northernmost waterfall. There is also the 2.8-mile (4.5 km) Ganoga View Trail, which leads from Pennsylvania Route 487 in the west to Ganoga Falls. The Highland Trail, which meets the Falls Trail a short distance north of Mohawk Falls, is the 1.2-mile (1.9 km) connector between the northern ends of Ganoga Glen and Glen Leigh.[3][45]

Jeff Mitchell writes in Hiking the Endless Mountains: Exploring the Wilderness of Northeast Pennsylvania that Ganoga Glen has his "favorite place" in the park: "Here the trail wraps around ledges and underneath overhanging rocks, right next to the waterfalls. The roar of the falls reverberates against their rocky confines. The state park trail map says that Seneca, Delaware, and Mohican Falls are here, but it is hard to discern which falls are which because they explode from everywhere and are continuous."[79]

| Name[3] | Height[3] | Elevation[34] | Coordinates[34] | Type[5] | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erie | 47 feet (14.3 m) | 1,608 feet (490 m)[80] | 41°19′18″N 76°16′40″W / 41.32167°N 76.27778°W | cascade |  |

| Erie Falls is one of two named waterfalls visible from Waters Meet (Wyandot Falls in Glen Leigh is the other). It is the first named falls in Ganoga Glen, and is 0.1 miles (0.16 km) upstream of Waters Meet.[33][45] The Erie were an Iroquoian-speaking people who lived on the southern shore of Lake Erie. They were destroyed as a people by 1656, as a result of a war with the Seneca and other Iroquois.[81] | |||||

| Tuscarora | 47 feet (14.3 m) | 1,713 feet (522 m)[82] | 41°19′17″N 76°16′46″W / 41.32139°N 76.27944°W | cascade, then falls |  |

| Tuscarora Falls is the second named falls in Ganoga Glen, and is a little more than 0.1 miles (0.16 km) upstream of Waters Meet.[33][45] The Tuscarora are an Iroquoian speaking people who originally lived in what is now North Carolina, then moved to New York. In 1713 the Tuscarora became the sixth member of the Iroquois Confederation, which then became known as the Six Nations.[83] During the American Revolutionary War, the Tuscarora and their allies the Oneida were the only Iroquois who supported the United States.[84] | |||||

| Conestoga | 17 feet (5.2 m) | 1,824 feet (556 m)[85] | 41°19′16″N 76°16′56″W / 41.32111°N 76.28222°W | slide |  |

| Conestoga Falls is the third named falls in Ganoga Glen, and is 0.3 miles (0.48 km) upstream of Waters Meet.[33][45] The Conestoga or Susquehannocks were an Iroquoian-speaking people who lived on the Susquehanna River, which is named for them; the park is in the Susquehanna's drainage basin. After the Iroquois defeated the Susquehannocks in war in 1675, the survivors were assimilated into other tribes, until the last members were killed by the Paxton Boys in 1763.[86] Brown calls Conestoga Falls "not particularly photogenic".[87] | |||||

| Mohican | 39 feet (11.9 m) | 1,788 feet (545 m)[88] | 41°19′18″N 76°16′58″W / 41.32167°N 76.28278°W | slide, then slide |  |

| Mohican Falls is the fourth named falls in Ganoga Glen, and is 0.4 miles (0.64 km) upstream of Waters Meet.[33][45] The Mohicans or Mahicans were an Algonquian speaking people who originally lived on the upper part of the Hudson River. They lost a prolonged war with the Mohawk nation and other Iroquois in 1673 and some later lived in Pennsylvania.[89] Mohican Falls consists of two slides, one above the other. Brown notes it is difficult to photograph both parts (only the top slide is pictured here).[90] | |||||

| Delaware | 37 feet (11.3 m) | 1,824 feet (556 m)[91] | 41°19′20″N 76°16′59″W / 41.32222°N 76.28306°W | slide |  |

| Delaware Falls is the fifth named falls in Ganoga Glen, and is 0.5 miles (0.80 km) upstream of Waters Meet.[33][45] The Delaware or Lenape are an Algonquian-speaking people who originally lived along the Delaware River and points east. The Lenape began selling land to William Penn in 1682; westward expansion of white settlers forced the last Lenape to leave Pennsylvania by 1772.[92][93] Brown notes Delaware Falls is easy to miss, despite its size.[90] | |||||

| Seneca | 12 feet (3.7 m) | 1,857 feet (566 m)[94] | 41°19′22″N 76°16′59″W / 41.32278°N 76.28306°W | slide |  |

| Seneca Falls is the sixth named falls in Ganoga Glen, and is a little more than 0.5 miles (0.80 km) upstream of Waters Meet.[33][45] The Seneca were an Iroquoian-speaking people and the westernmost of the original five tribes of the Iroquois Nation. As such they were known as the "Keepers of the Western Door" of the Iroquois Longhouse and were one of three "Elder Brothers" in the Confederacy. The two war chiefs of the Iroquois were chosen by the Seneca.[95] The Seneca had many trails through Pennsylvania and used the western part of the state as a hunting ground.[96] Brown notes Seneca Falls is also easy to miss.[90] | |||||

| Ganoga | 94 feet (28.7 m) | 1,962 feet (598 m)[97] | 41°19′26″N 76°17′02″W / 41.32389°N 76.28389°W | cascade | |

| Ganoga Falls is the seventh named falls in Ganoga Glen, and is 0.7 miles (1.1 km) upstream of Waters Meet.[33][45] Brown calls Ganoga Falls "the park's crown jewel", and notes that the creek changes direction near the top of the falls, "which causes the apparent size and shape of the falls to change with your perspective".[98] At Ganoga, short spurs lead from the Falls Trail to the base of the falls and to near the top of the falls, as well as to the Ganoga View Trail. People have fallen at Ganoga Falls and suffered serious injuries.[46] | |||||

| Cayuga | 11 feet (3.4 m) | 2,041 feet (622 m)[99] | 41°19′31″N 76°17′06″W / 41.32528°N 76.28500°W |  | |

| Cayuga Falls is the eighth named falls in Ganoga Glen, and is 0.8 miles (1.3 km) upstream of Waters Meet.[33][45] According to Brown, Cayuga Falls "just isn't photogenic".[100] The Cayuga are an Iroquoian-speaking people and one of the five original members of the Iroquois; their lands were between the central Onondaga and the westernmost Seneca. They were "Younger Brothers" in the Iroquois Confederation and were "affiliated with the Senecas".[95] | |||||

| Oneida | 13 feet (4.0 m) | 2,126 feet (648 m)[101] | 41°19′36″N 76°17′14″W / 41.32667°N 76.28722°W | falls |  |

| Oneida Falls is the ninth named falls in Ganoga Glen, and is 0.9 miles (1.4 km) upstream of Waters Meet.[33][45] Brown describes the pleasures of photographing this falls.[100] The Oneida are an Iroquoian-speaking people and one of the five original members of the Iroquois; their lands were between the central Onondaga and the easternmost Mohawk. They were "Younger Brothers" in the Iroquois Confederation and were "affiliated with the Mohawks".[95] During the American Revolutionary War, the Oneida and their allies the Tuscarora were the only Iroquois who supported the United States.[84] | |||||

| Mohawk | 37 feet (11.3 m) | 2,165 feet (660 m)[102] | 41°19′39″N 76°17′14″W / 41.32750°N 76.28722°W | falls, then slide |  |

| Mohawk Falls is the tenth and last named falls in Ganoga Glen, and is 1.1 miles (1.8 km) upstream of Waters Meet.[33][45] It is also 0.3 miles (0.48 km) south of the Lake Rose trailhead parking lot by Lake Jean.[3][45] Brown describes Mohawk Falls as a 9-foot (2.7 m) falls "with steeply descending, boulder-choked tailwaters".[100] The Mohawk were an Iroquoian-speaking people and the easternmost of the original five tribes of the Iroquois Nation. As such they were known as the "Keepers of the Eastern Door" of the Iroquois Longhouse and were one of three "Elder Brothers" in the Confederacy. The Mohawk also had a veto in the Iroquois council.[95] | |||||

Note

- a. ^ According to the USGS GNIS, Lake Rose at the head of Ganoga Glen is at an elevation of 2,201 feet (671 m) and Lake Leigh at the head of Glen Leigh is at 2,198 feet (670 m).[103][104] Adams Falls, at the base of Ricketts Glen, is at 1,214 feet (370 m), for a drop in elevation within the glens of just under 1,000 feet (300 m).[40]

- In Ganoga Glen, the drop from Mohawk Falls (at 2,165 feet (660 m)) to the mouth of the glen (at 1,578 feet (481 m)) is 587 feet (179 m) in 1.1 miles (1.8 km).[102][105] In the steeper Glen Leigh, the drop from Onondaga Falls (at 2,077 feet (633 m)) to the mouth of the glen (at 1,565 feet (477 m)) is 512 feet (156 m) in 0.73 miles (1.17 km).[73][106] Ricketts Glen is less step than either of the other glens; it drops about 360 feet (110 m) in the 1.8 miles (2.9 km) between Waters Meet and Pennsylvania Route 118.[40][41]

References

- 1 2 Young, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Braun, Duane D.; Inners, Jon D. "Pennsylvania Trail of Geology, Ricketts Glen State Park, Luzerne, Sullivan and Columbia Counties, The Rocks, the Glens and the Falls (Park Guide 13)" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Ricketts Glen State Park (PDF) (Map). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. June 20, 2014. and The Glens Natural Area (PDF) (Map). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved June 3, 2015. Note: These are two maps from the park guide giving 22 waterfall names and heights (all the falls except Kitchen Creek and Shingle Cabin).

- 1 2 3 4 "Kitchen Creek Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. August 2, 1979. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Brown, pp. 50–52.

- 1 2 Van Diver, pp. 31–35, 153–155.

- ↑ Shultz, pp. 372–374, 391, 399, 818.

- ↑ Bureau of Watershed Management, Division of Water Use Planning, Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (2001). Pennsylvania Gazetteer of Streams (PDF). Prepared in Cooperation with the United States Department of the Interior Geological Survey. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ↑ Berg, T. M. (1981). "Atlas of Preliminary Geologic Quadrangle Maps of Pennsylvania: Red Rock" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 20, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2015. Note: The entire "Atlas of Preliminary Geologic Quadrangle Maps of Pennsylvania" is available as a zip file at #61, here

- ↑ "Map 67: Tabloid Edition Explanation" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 14, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2015. Note: Map 67 is available as a zip file at #67, here

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Ricketts Glen State Park". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ↑ Brown, p. xiv

- ↑ Richter, pp. 3–46.

- ↑ Wallace, p. 159.

- ↑ Wallace, pp. 136–141.

- ↑ "Luzerne County 3rd class" (PDF). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- ↑ Wren, p. 56, Plate No. 7.

- 1 2 3 Ricketts, William Reynolds (1936). "William R. Ricketts House, North Mountain Colley, Ganoga Lake, Sullivan County, PA". Historic American Buildings Survey/Historic American Engineering Record. Library of Congress. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- 1 2 Petrillo, pp. 40–41.

- 1 2 3 4 Petrillo, pp. 42, 52.

- 1 2 Petrillo, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 4 "50,000 will see Rickett's Glen Charms". Williamsport Sun. September 4, 1947. p. 12.

- 1 2 3 Petrillo, p. 69.

- ↑ "Camp Information for SP-9-PA". Pennsylvania CCC Archive. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ↑ Paige, John C. (1985). "Appendix C, Table C-1: Directory of CCC Camps Supervised by the NPS (updated to December 31, 1941).". The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933–1942: An Administrative History. National Park Service, Department of the Interior. OCLC 12072830.

- ↑ "Ricketts Glen Project Sidetracked". Williamsport Gazette and Bulletin. February 28, 1936. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ↑ "Army drops poles into Ricketts Glen". The Resource. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. January 7, 1997. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Winter fun awaits visitors". The Resource. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. January 1998. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Ricketts Glen practices for rescues on ice". The Resource. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. March 7, 1997. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Ricketts Glen State Park begins project to shore up trail". The Resource. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. December 1998. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Readers' Choice Awards 2009". Backpacker. January 2009. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Readers' Choice Northeast Hikes: Ricketts Glen State Park, PA". Backpacker. January–February 2010. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Young, p. 70.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The elevation and coordinates are taken from the USGS GNIS report for each waterfall, except as noted.

- ↑ Bonta, p. 20.

- ↑ Faris, John T. (1919). Seeing Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company. p. 181. OCLC 1527147. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ↑ Young, p. 46.

- ↑ See the USGS GNIS entry for each waterfall.

- ↑ Mitchell, p. 41.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Young, pp. 66–71.

- 1 2 3 "Adams Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ↑ Heights for Kitchen Creek and Shingle Cabin Falls taken from Brown, pp. 51–52.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kline, David R. (January 6, 2010). "News From Back Home". Benton News. Benton, Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Tomasak, pp. 374–375.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Brown, pp. 53–64.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mitchell, pp. 44–47.

- ↑ "Shingle Cabin Brook". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. August 2, 1979. Retrieved November 17, 2009. Note: The waterfall is at the mouth of Shingle Cabin Brook, so the elevation and coordinates of the mouth are used.

- ↑ "Murray Reynolds Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ↑ Johnson, F.C., ed. (1905). "Death of Col. G. Murray Reynolds". The Historical Record of Wyoming Valley. A Compilation of Matters of Local History from the Columns of the Wilkes-Barre Record. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: Press of the Wilkes-Barre Record. XIII: 139–142. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Sheldon Reynolds Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ↑ Johnson, F.C., ed. (1897). "Sheldon Reynolds". The Historical Record: A Quarterly Publication Devoted Principally to the Early History of Wyoming Valley and Contiguous Territory with Notes and Queries Biographical, Antiquarian, Genealogical. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: Press of the Wilkes-Barre Record. VII: 31–36. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Harrison Wright Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 17, 2009.

- ↑ Kulp, pp. 1325–1362.

- ↑ "Papers Read Before the Wyoming Historical and Geological Society". Proceedings and Collections of the Wyoming Historical and Geological Society. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. 4: 185–188. 1898. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ↑ Bonta, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Petrillo, pp. 40, 68.

- 1 2 Gross, Doug (May 2004). "Pennsylvania Important Bird Area #48 (Formerly #48 & 49) North Mountain Including Ricketts Glen State Park and Dutch Mountain Wetlands, SGL 57, and SGL 13 (in part): Phase I Conservation Plan" (PDF). Pennsylvania Audubon Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2011. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Wyandot Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- 1 2 Thornton, pp. 72–75.

- ↑ "B Reynolds Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ↑ Petrillo, pp. 42–43, 69.

- ↑ "R B Ricketts Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ↑ Petrillo, p. 49.

- ↑ "Ozone Falls (Pennsylvania)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ↑ "Ozone Falls (Tennessee)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. May 19, 1980. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- ↑ "Ozone Falls Class I Scenic-Recreational State Natural Area". Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ↑ "Huron Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ↑ "Shawnee Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ↑ Donehoo, pp. 192–197.

- ↑ Wallace, pp. 125–128.

- ↑ "F L Ricketts Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ↑ Tomasak, pp. 326, 374–375.

- 1 2 "Onondaga Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 19, 2009.

- ↑ Wallace, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Donehoo, p. 136–137.

- ↑ Bachelder, pp. 186–189.

- ↑ Petrillo, p. 42.

- ↑ Donehoo, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Mitchell, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ "Erie Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. December 1, 1989. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ↑ Donehoo, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ "Tuscarora Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ↑ Donehoo, pp. 71, 72, 237–240.

- 1 2 Donehoo, p. 136.

- ↑ "Conestoga Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- ↑ Donehoo, p. 34–38.

- ↑ Brown, p. 60.

- ↑ "Mohican Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ↑ Wallace, pp. 18, 103.

- 1 2 3 Brown, p. 61.

- ↑ "Delaware Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ↑ Donehoo, pp. 53–55.

- ↑ Wallace, pp. 139–152.

- ↑ "Seneca Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Wallace, pp. 90, 93.

- ↑ Donehoo, pp. 177–183.

- ↑ "Ganoga Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ↑ Brown, p. 62.

- ↑ "Cayuga Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Brown, p. 63.

- ↑ "Oneida Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- 1 2 "Mohawk Falls". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. September 1, 1989. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Lake Rose". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. August 2, 1979. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Lake Leigh". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. August 2, 1979. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Ganoga Glen". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. August 2, 1979. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Glen Leigh Valley". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. August 2, 1979. Retrieved January 30, 2010.

Works cited

- Bachelder, John B. (1875). Popular resorts, and how to reach them. Combining a Brief Description of the Principal Summer Retreats in the United States, and the Routes of travel Leading to Them. Boston, Massachusetts: J.B. Bachelder Publishing. OCLC 317328980.

- Bonta, Marcia (1987). Outbound Journeys in Pennsylvania: A Guide to Natural Places for Individual and Group Outings. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-00606-4.

- Brown, Scott E. (2004). Pennsylvania waterfalls: a guide for hikers and photographers. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-3184-7.

- Donehoo, George P. (1999) [1928]. A History of the Indian Villages and Place Names in Pennsylvania (PDF) (Second Reprint ed.). Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Wennawoods Publishing. ISBN 1-889037-11-7. Retrieved June 3, 2015. ISBN refers to a 1999 reprint edition, URL is for the Susquehanna River Basin Commission's web page of Native American Place names, quoting and citing the book

- Kulp, George Brubaker (1890). Families of the Wyoming Valley: Biographical, Genealogical and Historical. Sketches of the Bench and Bar of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania. 3. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: E.B. Yordy.

- Mitchell, Jeff (2003). "13. Falls Trail (Ricketts Glen State Park)". Hiking the Endless Mountains: Exploring the Wilderness of Northeast Pennsylvania. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-2648-7.

- Petrillo, F. Charles (1991). Ghost Towns of North Mountain: Ricketts, Mountain Springs, Stull (PDF). Wyoming Historical & Geological Society. OCLC 25080093.

- Richter, Daniel K. (2002). "Chapter 1. The First Pennsylvanians". In Miller, Randall M.; Pencak, William A. Pennsylvania: A History of the Commonwealth. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. ISBN 0-271-02213-2.

- Shultz, Charles H. (Editor) (1999). The Geology of Pennsylvania. Harrisburg and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Geological Society and Pittsburgh Geological Society. pp. 372–374, 391, 399, 818. ISBN 0-8182-0227-0.

- Tomasak, Peter (2008). In Command of Time Elapsed: The Life and Times of Robert Bruce Ricketts. Kyttle, Pennsylvania: North Mountain Publishing Company.

- Thornton, Russell (1990). American Indian holocaust and survival: a population history since 1492. The Civilization of the American Indians series. 186. Norman, Oklahoma: The University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2220-X.

- Van Diver, Bradford B. (1990). Roadside Geology of Pennsylvania. Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87842-227-7.

- Wallace, Paul A.W.; revised by William A. Hunter (2005). Indians in Pennsylvania (Second ed.). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. ISBN 978-1-4223-1493-7. OCLC 1744740. (Note: OCLC refers to the 1961 First Edition).

- Wren, Christopher; Wyoming Historical and Geological Society (1914). A Study of North Appalachian Indian Pottery. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: E.B. Yordy Co. OCLC 2510750.

- Young, John (2001). Hike Pennsylvania: An Atlas of Pennsylvania's Greatest Hiking Adventures. Guilford, Connecticut: The Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 0-7627-0924-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ricketts Glen State Park. |

- "Ricketts Glen State Park Official map" (PDF). (1.888 MB)

- "Ricketts Glen State Park Glens Natural Area map" (PDF). (3.269 MB)

- "Ricketts Glen State Park Recreational Guide" (PDF). (0.505 MB)

,