Walter Shaw Sparrow

| Walter Shaw Sparrow | |

|---|---|

| Born |

1862 Cymmau Hall, Flintshire, Wales[1] |

| Died | 11 March 1940 (aged 78) |

| Occupation | Writer and art critic |

| Known for | books about British sporting artists |

Walter Shaw Sparrow (1862–1940) was a British writer on art and architecture with a special interest in British sporting artists.[2]

Biography

Childhood

Sparrow was born in 1862, younger son of James Sparrow JP FGS (1824–1902)[3] and his wife Caroline (1828–1904),[4] of Gwersyllt Hill, near Wrexham, Wales.[5] In 1855, James Sparrow had become proprietor of Ffrwd Works,[6] a large colliery, ironworks and brickworks between Brymbo and Cefn-y-bedd which he expanded into one of the most prominent businesses in North Wales.[7] During his boyhood Sparrow got to know many of his father's colliers, furnacemen, blacksmiths, carpenters and farm workers, and gained a respect and admiration for the men he described as "so big, strong, simple-hearted, and kind".[1] He made a study of the cruel conditions endured by coal miners and the fact that nationally over a thousand colliers were killed every year in accidents, and this engendered in him a desire to see fairness for working men.[1]

Sparrow started school at Chester College, which, he recounts, was "devoted to science", and opened his eyes to botany, chemistry and physiology. His early drawing lessons there were based on observation from nature.[8] After Chester College he went to Newton Abbott College in South Devon, where Arthur Quiller-Couch was one of his contemporaries.[8] He distinguished himself with a first prize in political economy and for his drawing skills.[8] He also mentions his admiration for the watercolour painting skills of the headmaster's wife, whom he got to know during an illness at the college.[9]

During the long school holidays at home in his early teens (1875–1879), he spent some time with professional artist William Joseph J. C. Bond, who was staying with the family. Bond painted in oils, and Sparrow learnt techniques from him, and insight into pigments and varnishes and problems with their stability.[9] It was after discussing with Bond and with Walter's uncle, the architect George T. Robinson, that his father decided to approve Walter attending the Slade School of Fine Art in London, where he studied under artist Alphonse Legros for fifteen months.[9]

Adult life

In 1880, his father decided to send him to Brussels to study at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts under Jean-François Portaels, Joseph Stallaert and Joseph van Severdonck.[5] Before starting his studies there, he went with his parents on an artistic and historical tour of Belgium,[9] after which he remained in Brussels for seven years, but returned home for holidays.[9] He established a small studio in Brussels at the suggestion of van Severdonck, and was supported by money from home, but earned extra income by giving drawing classes and English lessons, as well as selling a few paintings and writing four little articles which were accepted for publication in The Globe newspaper by the then editor, Ponsonby Ogle.[8]

Sparrow returned to London in spring 1888, where he took two rooms in Kennington Park, initially with his brother Wilfrid.[8] He played some minor roles in theatre productions, including some Shakespeare plays,[9] and joined F. R. Benson's Shakespearean company, whose leading actresses included Ada Ferrar and Constance Featherstonhaugh (who later married Benson).[1]

In April 1891 Sparrow married Ada Ferrar (sometimes referred to as Ada Bishop), and the officials and workmen of the Ffrwd Works, his father's colliery, marked the occasion by presenting the couple with a "very chaste silvered tea and coffee service" with their best wishes.[10] During the 1890s and into the twentieth century Ada continued to feature prominently on the cast of many theatrical productions. Very soon after their marriage, in May and June 1891, the magazine Theatre commended her performance as Alida in The Streets of London by Dion Boucicault at the Royal Adelphi Theatre in London.[11] And from 1896 to 1899 she took part in many productions with a group of actors on an extended overseas tour, performing as far afield as Australia and New Zealand, returning to England in September 1899.[12] Her performance as Mercia in Wilson Barrett's The Sign of the Cross was particularly well received.

1899 proved to be something of a turning point for Sparrow. The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society were staging their sixth exhibition at the New Gallery, Regent Street, London,[13] featuring a William Morris retrospective, and Sparrow produced publicity for the exhibition for The Studio magazine.[9] After the exhibition, he was appointed assistant art editor of The Studio, a post in which he continued for the next four and a half years.[2]

His father died in 1902 and in 1904 the Ffryd works closed owing to difficult business conditions.[7] Little trace of the industrial complex now remains.[14]

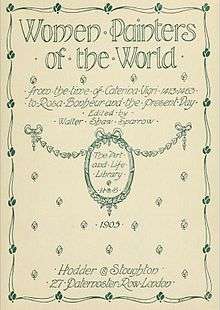

After leaving The Studio, Sparrow founded and edited the Art and Life Library",[2] writing a series of books on art, architecture and furniture for over thirty years, as well as contributing numerous articles to magazines and newspapers. He particularly admired the work of Frank Brangwyn, and Brangwyn produced the illustrations for several of his books.[9] In 1925 he wrote Memories of life and art through sixty years, an account of his life up to that point, described as "discursive and somewhat unmethodical in treatment," but "not lacking in interest and entertainment, for Sparrow had met most of the most important figures in the professional circles of his time."[2] But he is best remembered for his books on sporting artists, and he took delight in researching what he called "family news" from parish registers, wills and other documents, in the process discovering several errors in the previously accepted information about English sporting artists.[2] His literary style has been described as creating "a charmed sphere of refined diction and cultivated thought."[1]

Sparrow died on 11 March 1940[5] at the age of 78.[2] After his death, his wife was awarded a £100 Civil list pension under the Civil List Act 1837 for the "writings of her husband, the late Walter Shaw Sparrow, on art and architecture".[15] In 1942, Edward Croft-Murray gave five drawings of named racehorses by the eighteenth century horse painter James Seymour to the British Museum "in memory of the late Walter Shaw Sparrow".[16]

Works

His books included the following,[5][17] and he also wrote numerous magazine articles.

- 1904 – The British Home of To-Day[18]

- 1904 – The Gospels in Art[19]

- 1905 – The Old Testament in Art[20]

- 1905 – Women Painters of the World

- 1905 – The Spirit of the Age

- 1906 – The Modern Home[21]

- 1908 – The English House[22]

- 1908 – Old England[23]

- 1909 – Our Homes and How to Make the Best of Them[24]

- 1911 – Frank Brangwyn and His Work[25]

- 1912 – John Lavery and His Work[26]

- 1915 – A Book of Bridges[27]

- 1919 – Prints and Drawings by Frank Brangwyn[28]

- 1921 – The Fifth Army in March 1918[29]

- 1922 – British Sporting Artists from Barlow to Herring[30]

- 1923 – Angling in British art through five centuries

- 1924 – Advertising and British art

- 1925 – Memories of life and art through sixty years

- 1926 – A Book of British Etching[31]

- 1926 – Brian Hatton – a young painter of genius killed in the War

- 1927 – Henry Alken

- 1929 – George Stubbs and Ben Marshall

- 1929 – Charles Towne

- 1931 – A Book of British Sporting Painters[32]

- 1932 – John Boultbee, Thomas Weaver[32]

- 1934 – A. Frederick Sandys

- 1937 – Studies in early Turf history

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gerald Marr Thompson (6 November 1926). "Art Life in London". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Mr. W. S. Sparrow (obituary)". The Times. London: The Times Digital Archive (48576): 11. 29 March 1940. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ "James Sparrow of Gwersyllt Hill (1824–1902), Proprietor of Ffrwd Colliery and Ironworks". BBC. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ "Caroline Sparrow (1828–1904), Wife of James Sparrow". BBC. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 A & C Black (December 2007). "Sparrow, Walter Shaw". Who Was Who. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ Philip Coops (27 March 2012). "Timeline to the Broughton Area". Broughton District History Group. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- 1 2 "Life in Victorian Brick Works – Brick Gallery". 2 March 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Walter Shaw Sparrow (1925). Memories of life and art through sixty years. John Lane. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "W.S. Sparrow: memories of life and art, through sixty years:". Australian Postal History & Social Philately. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ "Ffrwd". The Wrexham Advertiser, and North Wales News. Wrexham, Wales: Gale: 19th Century British Library Newspapers: 8. 18 April 1891. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ↑ Meredith Klaus (ed.) (14 February 2011). "Seasonal Summary for 1890–1891". The Adelphi Theatre 1806–1900. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ "Miss Ada Ferrar – An Interview". The South Australian Register. 24 May 1899. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ "Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society: Sixth Exhibition, 1899 – Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851–1951". Glasgow University. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ "Gwersyllt, Cefnybedd, Caergwrle". Penmorfa. 24 January 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- ↑ "Civil List Pensions". The Times. London: The Times Digital Archive (48907): 2. 23 April 1941. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ "Drawings for the Nation". The Times. London: The Times Digital Archive (49150): 7. 3 February 1942. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ "Walter Shaw Sparrow – Available Works". UNZ. 20 March 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- ↑ "The British Home of To-Day (1904) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "The Gospels in Art (1904) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "The Old Testament in Art (1905) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "The Modern Home (1906) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "The English House (1908) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "Old England (1908) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "Our Homes and How to Make the Best of Them (1909) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "Frank Brangwyn and His Work (1911) , by Walter Shaw-Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "John Lavery and His Work (1912) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "A Book of Bridges (1915) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "Prints and Drawings by Frank Brangwyn (1919) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "The Fifth Army in March 1918 (1921) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "British Sporting Artists from Barlow to Herring (1922) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- ↑ "A Book of British Etching (1926) , by Walter Shaw Sparrow". UNZ.org.

- 1 2 "SPARROW, Walter Shaw : Who's Who". ukwhoswho.com. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

External links

- Works by Walter Shaw Sparrow at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Walter Shaw Sparrow at Internet Archive