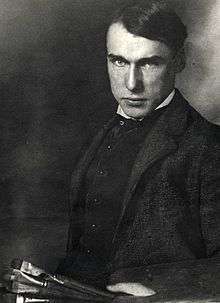

Walt Kuhn

| Walt Kuhn | |

|---|---|

circa 1904 | |

| Born | October 27, 1877 |

| Died | July 13, 1949 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting, modern art |

Walt Kuhn (October 27, 1877 – July 13, 1949) was an American painter and an organizer of the famous Armory Show of 1913, which was America's first large-scale introduction to European Modernism.

Biography

Kuhn was born in New York City in 1877. Growing up near the Brooklyn docks in a working-class family, he was exposed to a range of rough, colorful waterfront experiences in his youth and, though he loved to draw, nothing in his background suggested a future career in art. Kuhn's first jobs were as a proprietor of a bicycle repair shop and as a professional bike racer. At fifteen, though, Walter Kuhn sold his first drawings to a magazine and began to sign his name “Walt.” In 1893, deciding that he would benefit from some formal training, he enrolled in art classes at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute.[1]

In 1899, Kuhn set out for California with sixty dollars in his pocket. Upon his arrival in San Francisco, he became an illustrator for WASP Magazine. It was at this time that he decided, if wanted to grow and eventually make a living as an artist, he should expose himself to the Old Masters and the modern artists of Europe. In 1901, at the age of twenty-four, Kuhn left for Paris. There he studied briefly art at the Académie Colarossi before leaving to the Royal Academy in Munich. Once in the capital of Bavaria, he studied under Heinrich von Zügel, a member of the Barbizon School. He went on sketching trips in the Netherlands and toured the museums of Venice. During his two-year stay abroad, Kuhn also saw for the first time the work of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists.[2]

In 1903, he returned to New York and was employed as an illustrator for local journals. In 1905, he held his first exhibition at the Salmagundi Club, establishing himself as both a cartoonist and a serious painter. In this same year, he completed his first illustrations for Life magazine. In 1909-10, his strip "Whisk" ran for almost two years in the New York World. He counted a number of cartoonists and illustrators among his friends, including Gus Mager and Pop Hart.[3]

When the New York School of Art moved to Fort Lee, New Jersey in the summer of 1908, Kuhn joined the faculty. However, he disliked his experience with the school, and at the end of the school year, he returned to New York. There, he married Vera Spier. Soon after, a daughter, Brenda Kuhn, was born. An important friendship was formed at this time with artist Arthur Bowen Davies, who would also play a significant role in American art history.[4]

In 1909, Kuhn had his first solo exhibition in New York. In the following years, he took part in founding the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, the organization ultimately responsible for the Armory Show. Kuhn acted as the executive secretary and was delegated as one of the men to find European artists to participate. He, Davies, and artist Walter Pach made a whirlwind tour of Europe in 1912 to find the best and most audacious examples of new art to introduce to New York audiences. The Armory Show of 1913, which displayed both European and American modernist art, resulted in both an historic controversy and a long-range triumph. Smart and sensational publicity, combined with strategic word-of-mouth, resulted in attendance figures of over 200,000 and over $44,000 in sales, far exceeding anyone's expectations for the venture.[5] After its New York venue, the Armory Show toured, receiving widespread attention, in Chicago and Boston. "Kuhn had a talent for promotion," art critic Robert Hughes has noted.[6] This unprecedented exhibition had demonstrated that Americans might be receptive to modern art and that there was a large potential market for it; Kuhn played a major role in a transformative cultural event.[7]

Following the Armory Show, Kuhn acted as an art advisor to the lawyer and collector John Quinn and assisted in the formation of his unique collection of modern art, unfortunately dissolved and sold at the time of Quinn's death in 1924.[8] He also exhibited with the Whitney Studio Club and became a much-appreciated artist at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Kuhn's work in the 1910s often showed the influence of the modern European painters whose art he had helped to promote. The Polo Ground (1914), for instance, contains strong echoes of Raoul Dufy.[9] Other critics noted an affinity for André Derain and the German Expressionists. By the end of the decade, though, Kuhn's paintings had become more traditionally representational again, though he never worked in the manner of an academic realist; his portraits and still lifes are composed of broad painterly effects, strong colors, and thick textures. In brushstroke and intensity, a Kuhn face or still life in unmistakably Kuhn's.

In 1925, Kuhn almost died from a duodenal ulcer. Following an arduous recovery, he became an instructor at the Art Students League of New York. He also completed a commission for the Union Pacific Railroad, the club car "The Little Nugget" LA-701, currently under restoration at the Travel Town Museum in Los Angeles, California. In 1933, the aging artist organized his first retrospective. During these years, he began to question his earlier allegiance to European Modernism. On a 1931 trip to Europe with Marie and W. Averell Harriman, his staunchest supporters, he declined to join the Harrimans on their visits to the studios of Picasso, Georges Braque, and Fernand Léger.[10] Yet neither did he want to align himself with the anti-Modernist camp of Regionalists like Thomas Hart Benton and politically-minded social realists. In the art politics of the day, Kuhn was caught between two extremes.

By the 1940s, Kuhn’s behavior began to take on unsound characteristics. He became increasingly irascible and distant from old friends. When the Ringling Brothers Circus was in town, he attended night after night. (During a hard-pressed period in the 1920s, Kuhn had worked as a designer and director for revues and circus acts.) He also became frustrated by the lack of attention his own work was receiving and was particularly strident about the Museum of Modern Art's support of abstraction and neglect of American art in the postwar period.[11] In 1948, he was institutionalized, and on July 13, 1949, he died suddenly from a perforated ulcer. He is interred in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.

Work

Walt Kuhn is best remembered today for his key role in planning the Armory Show. Ironically, a man who was in the forefront of the modern movement and was seen as an advocate of adventurous new art in 1913 came to be labelled, because of his on-going commitment to representation, a conservative artist by future generations of art historians.[12] Nevertheless, he holds a place in American art history as a skilled cartoonist, draughtsman, printmaker, sculptor and painter. Although he destroyed many of his early paintings, his works that remain today are powerful and are a part of most major American art collections.

His portraits of circus and vaudeville entertainers are some of the most memorable, confidently painted works of twentieth-century American art. They are reminiscent of commedia dell'arte actor portraits done by the French masters centuries earlier. The Tragic Comedians (1916) in the collection of the Hirshhorn Museum and The White Clown (1929) in the collection of the National Gallery of Art are intense, arresting images and are among his most respected paintings.

Selected catalogues and exhibitions

- Walt Kuhn (1877-1949) - American Modernist at sullivangoss.com

- DC Moore Gallery Exhibition, "Trees," June 11-August 7, 2009

- DC Moore Gallery Exhibition, "Modern America 1917-1944," November 17-December 23, 2011

- DC Moore Gallery Exhibition "Walt Kuhn: American Modern," February 7-March 16, 2013

- 1908-12, 1921, 1945-49: Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts exhibitions

- 1911: Madison Gallery, New York

- 1913: Armory Show, New York

- 1932-48: Whitney Museum of American Art exhibitions

- 1966: University of Arizona Art Gallery, Tucson

- 1967-68, 1972, 1977, 1980: Kennedy Galleries, New York

- 1984: Barridoff Galleries, Portland, ME

- 1987: Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

- 1987: Salander O’Reilly Galleries Inc., New York

- 1989: Maine University Art Museum, ME

References

- ↑ Biographical information for this entry is taken from Philip Rhys Adams.

- ↑ Adams, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ Suiter, Tad. "The Cartoonist as Artist, part 4. The Leisurely Historian website.

- ↑ Adams, p. 30. The relationship between Kuhn and Davies is chronicled in Bennard B. Perlman, The Lives, Loves, and Art of Arthur B. Davies (Albany: State University Press of New York, 1998).

- ↑ McShea, Megan, A Finding Aid to the Walt Kuhn Family Papers and Armory Show Records, 1859-1978 (bulk 1900-1949). Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- ↑ Robert Hughes, American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America (New York: Knopf, 1997), p. 354.

- ↑ Kuhn's essay "The History of the Armory Show" is reprinted in Arts Magazine (Summer 1984), pp. 138-141. The definitive account of the Armory Show remains art historian Milton Brown's study of the show's inception, organization, and reception.

- ↑ The relationship between Kuhn and Quinn, one of the great connoisseurs of his time, is chronicled extensively in B.L. Reid, The Man from New York: John Quinn and His Friends (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968).

- ↑ Adams, p. 65.

- ↑ Adams, p. 133.

- ↑ Kuhn is quoted on this subject in Time, November 22, 1948, p. 52.

- ↑ A critical but not unsympathetic account of Kuhn's art and its changes over the years can be found in Milton Brown, pp. 141-144. Brown writes: "Kuhn's Expressionism is conservative, but it has emotional depth."

Sources

Adams, Philip Rhys. Walt Kuhn: Painter, His Life and Work. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1978.

Brown, Milton. The Story of the Armory Show. New York: Abbeville, 1988 edition.

"Walt Kuhn: American Modern" (exhibition catalogue), DC Moore Gallery, March 2013

Loughery, John. "The Contradictions of Walt Kuhn," Arts Magazine (April 1985), pp. 106–107.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Walt Kuhn. |

- Biography

- Walt Kuhn, Kuhn Family Papers, and Armory Show records online at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- DC Moore Gallery artist page

- Antiques, January/February 2013, "Walt Kuhn at DC Moore"

- Harper's Bazaar, "An Avant-Garde Pioneer Gets His Due,"