Urania's Mirror

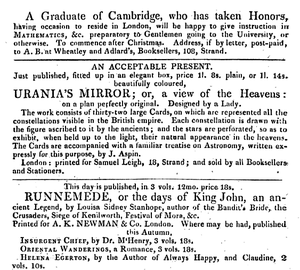

Urania's Mirror; or, a view of the Heavens is a set of 32 astronomical star chart cards, first published in November 1824.[1][2] They had illustrations based on Alexander Jamieson's A Celestial Atlas,[2] but the addition of holes punched in them allowed them to be held up to a light to see a depiction of the constellation's stars.[1] They were engraved by Sidney Hall, and were said to be designed by "a lady", but have since been identified as the work of the Reverend Richard Rouse Bloxam, an assistant master at Rugby School.[3]

The cover of the box-set showed a depiction of Urania, the muse of astronomy, and came with a book entitled A Familiar Treatise on Astronomy... written as an accompaniment.[2][4] P. D. Hingley, the researcher who solved the mystery of who designed the cards a hundred and seventy years after their publication, considers them amongst the most attractive star chart cards of the many produced in the early 19th century.

Description

.jpg)

Urania's Mirror illustrates 79 constellations, some of which are now obsolete, and various subconstellations, such as Caput Medusæ (the head of Medusa, carried by Perseus).[2] It was originally advertised as including "all the constellations visible in the British Empire",[1][4] but, in fact, leaves out the southern constellations and, by the second edition, advertisements merely claimed illustration of the constellations visible from "Great Britain".[4] Some cards focus on a single constellation, others include several, with Card 32, centered on Hydra, illustrating twelve constellations (several of which are no longer recognised). Card 28 has six, and no other card has more than four.[2] Each card measures 8 inches by 5 1⁄2 (about 20 by 14 cm).[4] A book by Jehoshaphat Aspin entitled A Familiar Treatise on Astronomy (or, to give its full name, A Familiar Treatise on Astronomy, Explaining the General Phenomena of the Celestial Bodies; with Numerous Graphical Illustrations) was written to accompany the cards.[2] Both the book and cards were originally published by Samuel Leigh, 18 Strand, London,[4] although the publishing firm had moved to 421 Strand and changed its name to M. A. Leigh by the fourth edition.[5] The cards and books came within a box illustrated with a woman almost certainly intended to be Urania, muse of astronomy.[4]

P.D. Hingley calls it "One of the most charming and visually attractive of the many aids to astronomical self-instruction produced in the early nineteenth century".[4] On its main gimmick, the holes in the stars meant to show the constellation when held in front of a light, he notes that, as the size of the holes marked correspond to the magnitude of the stars, a quite realistic depiction of the constellation is provided.[4] Ian Ridpath mostly concurs. He describes the device as an "attractive feature", but notes that, due to the light at the time being provided primarily by candles, many cards likely burned up due to carelessness when trying to hold them in front of the flame. He notes three other attempts to use the same gimmick—Franz Niklaus König's Atlas céleste (1826), Friedrich Braun's Himmels-Atlas in transparenten Karten (1850), and Otto Möllinger's Himmelsatlas (1851), but states that they lack Urania's Mirror's artistry.[2]

Copying from A Celestial Atlas

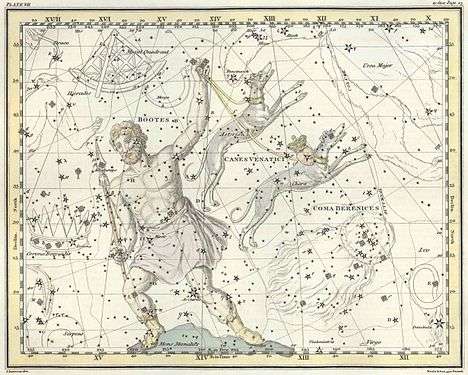

A Celestial Atlas, Plate 7

A Celestial Atlas, Plate 7 Urania's Mirror, Plate 10

Urania's Mirror, Plate 10

The depictions of the constellations are redrawn from those in Alexander Jamieson's A Celestial Atlas, published about three years earlier, and include unique quirks of Jamieson's sky atlas, including the new constellation of Noctua the owl, and "Norma Nilotica" – a measuring device for the Nile floods – held by Aquarius the water bearer.[2]

Mystery of the designer, and solution

Advertisements for Urania's Mirror, as well as the introduction to its companion book A Familiar Treatise on Astronomy, credit the design of the cards simply to a "lady", who is described in the introduction of the book as being "young". This led to speculation for over a century; some proposed prominent female astronomers such as Caroline Herschel and Mary Somerville, others credited the engraver Sidney Hall, but no guess was seen as a particularly credible fit.[4] The designer's real identity was not discovered for some 170 years; in 1994, while archiving early election certificates used to propose people to be admitted to the Royal Astronomical Society, P. D. Hingley found one proposing the Reverend Richard Rouse Bloxam and naming him as "Author of Urania's Mirror".[3] While he had several notable sons, he has no other known publications, his main distinction being to have served as assistant master at Rugby School for 38 years.[3]

The reasons for the disguise are unknown. Hingley notes that many contemporary publications attempted to suggest women had played a role in their creation, perhaps to make them sound less threatening. He suggests that anonymity might have been necessary to protect Bloxam's position at Rugby, but notes Rugby was quite progressive, which makes this unlikely; and, finally, suggests modesty as a possibility.[6] Ian Ridpath, noting the plagiarism of the art from A Celestial Atlas, suggests that this alone might be sufficient to cause the author to wish to remain anonymous.[2]

Editions

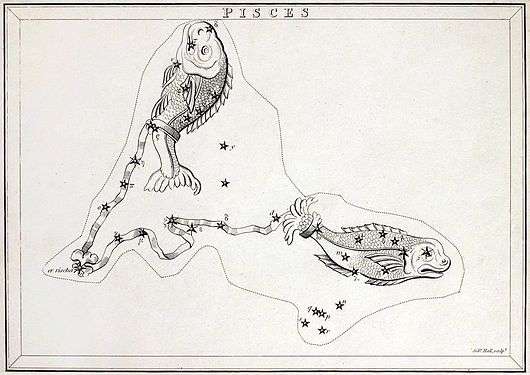

First edition "Pisces", without stars in the surrounding constellations. "Plain".

First edition "Pisces", without stars in the surrounding constellations. "Plain". Second edition "Pisces", with the surrounding stars. "Fully coloured".

Second edition "Pisces", with the surrounding stars. "Fully coloured".

A December 1824 advertisement, which states the cards were "just published", offered the cards "plain" at £1/8s or "fully coloured" for £1/14s.[1] This first edition did not include any stars surrounding the named constellations, leaving those parts blank. This was changed for the second edition, which added back stars around theose constellations.[2] An American edition was published in 1832. Modern reprints were produced in 1993, and Barnes & Noble reproduced the American edition (with accompanying book) in 2004.[2] The accompanying book, A Familiar Treatise on Astronomy by Jehoshaphat Aspin went through at least four editions, with the last coming out in 1834.[2] The second edition featured a marked expansion in content, growing from 121 pages in the first edition to 200 pages in the second.[4] The book, by the time of the 1834 American edition, consisted of an introduction, a list of the northern and southern constellations, a description of each of the plates, with the history and background of the constellations depicted, and an alphabetical list of named stars (such as Achernar) with their Bayer designation, magnitude, and respective constellation.[7]

A "Second Part" of Urania's Mirror, which was to have included illustrations of the planets and a portable orrery, was advertised,[8] but no evidence exists to show it was ever released.[2]

Gallery

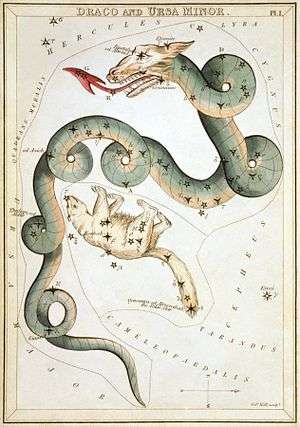

Plate 1: Draco and Ursa Minor

Plate 1: Draco and Ursa Minor

.jpg) Plate 3: Cassiopeia

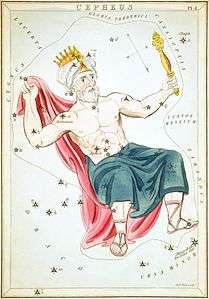

Plate 3: Cassiopeia Plate 4: Cepheus

Plate 4: Cepheus

Plate 6: Perseus and Caput Medusæ

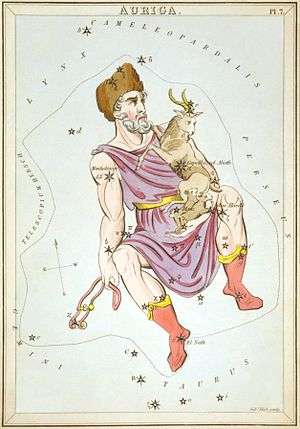

Plate 6: Perseus and Caput Medusæ Plate 7: Auriga

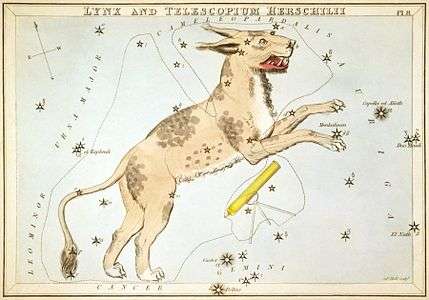

Plate 7: Auriga Plate 8: Lynx and Telescopium Herschilii

Plate 8: Lynx and Telescopium Herschilii Plate 9: Ursa Major

Plate 9: Ursa Major

Plate 11: Hercules and Corona Borealis

Plate 11: Hercules and Corona Borealis

.jpg)

Plate 16: Aries and Musca Borealis

Plate 16: Aries and Musca Borealis Plate 17: Taurus

Plate 17: Taurus Plate 18: Gemini

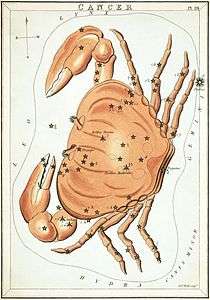

Plate 18: Gemini Plate 19: Cancer

Plate 19: Cancer

Plate 21: Virgo

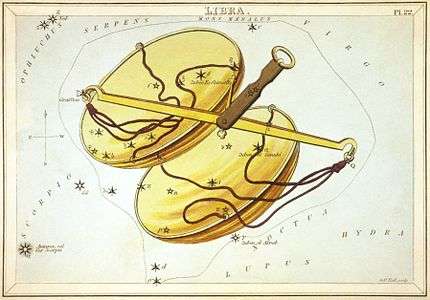

Plate 21: Virgo Plate 22: Libra

Plate 22: Libra Plate 23: Scorpio

Plate 23: Scorpio

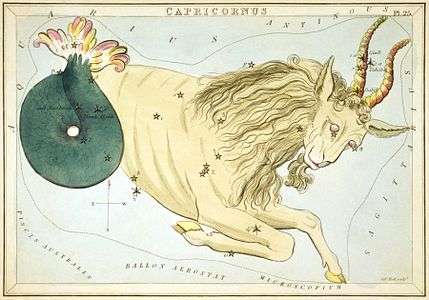

Plate 25: Capricornus

Plate 25: Capricornus

Plate 27: Pisces

Plate 27: Pisces Plate 28: Psalterium Georgii, Fluvius Eridanus, Cetus, Officina Sculptoris, Fornax Chemica, and Machina Electrica

Plate 28: Psalterium Georgii, Fluvius Eridanus, Cetus, Officina Sculptoris, Fornax Chemica, and Machina Electrica.jpg) Plate 29: Orion

Plate 29: Orion

Plate 32: Noctua, Corvus, Crater, Sextans Uraniæ, Hydra, Felis, Lupus, Centaurus, Antlia Pneumatica, Argo Navis, and Pyxis Nautica

Plate 32: Noctua, Corvus, Crater, Sextans Uraniæ, Hydra, Felis, Lupus, Centaurus, Antlia Pneumatica, Argo Navis, and Pyxis Nautica

Constellations depicted

The constellations depicted, in the order they are listed on the cards, are:[2]

- Draco

- Ursa Minor

- Camelopardalis

- Tarandus (obsolete, representing a reindeer, also called Rangifer)[10]

- Custos Messium (obsolete, literally translated as the Harvest Keeper, but intended as a pun on the comet hunter Charles Messier.)[11]

- Cassiopeia

- Cepheus

- Gloria Frederici (obsolete, also called Honores Friderici, meant to commemorate Frederick the Great)[12]

- Andromeda

- Triangula

- Perseus

- Auriga

- Lynx

- Telescopium Herschilii (obsolete, the Telescope of William Herschel)[13]

- Ursa Major

- Boötes

- Canes Venatici

- Coma Berenices

- Quadrans Muralis (obsolete, created by Lalande to commemorate the wall-mounted quadrant he and his nephew used to measure star positions)[14]

- Hercules

- Corona Borealis

- Taurus Poniatowski (obsolete, represented the bull on King Stanisław August Poniatowski's coat of arms. Also called Taurus Poniatovii.)[15]

- Serpentarius (a former name for Ophiuchus)[2]

- Scutum Sobiesky (Full name of the constellation Scutum, the Shield of King John III Sobieski.)[16]

- Serpens

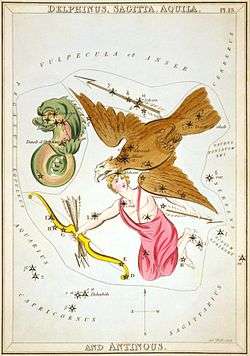

- Delphinus

- Sagitta

- Aquila

- Antinous (obsolete, Antinous was the lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian.)[17]

- Lacerta

- Cygnus

- Lyra

- Vulpecula and Anser (a slightly Anglicised version of the full name of Vulpecula, this translates as, "the little fox and the goose".)[18]

- Pegasus

- Equuleus

- Aries

- Musca Borealis (obsolete, represented a fly, not to be confused with the modern southern constellation of Musca.)[19]

- Taurus

- Gemini

- Cancer

- Leo Major (now known as Leo)

- Leo Minor

- Virgo

- Libra

- Scorpio

- Sagittarius

- Corona Australis

- Microscopium

- Telescopium

- Capricornus

- Aquarius

- Piscis Australis (a.k.a. Piscis Austrinus)

- Ballon Aerostatique (obsolete, honoured the Montgolfier brothers' balloon, also called Globus Aerostaticus)[20]

- Pisces

- Psalterium Georgii (obsolete, the harp of King George III of the United Kingdom. Also called Harpa Georgii.)[21]

- Fluvius Eridanus (former name of Eridanus)[22]

- Cetus

- Officina Sculptoris (now known as Sculptor)

- Fornax Chemica (full name of Fornax)

- Machina Electrica (obsolete, represented an electrostatic generator)[23]

- Orion

- Canis Major

- Lepus

- Columba Noachi (full name of Columba)[24]

- Cela Sculptoris (now known as Caelum)[2]

- Monoceros

- Canis Minor

- Atelier Typographique (obsolete, represented Gutenberg's printing shop)[25]

- Noctua (obsolete, an owl replacing the equally obsolete Turdus Solitarius, the thrush)[26]

- Corvus

- Crater

- Sextans Uraniae (original name of Sextans),[27]

- Hydra

- Felis (obsolete, represented a cat)[28]

- Lupus

- Centaurus

- Antlia Pneumatica (full name of Antlia)[29]

- Argo Navis (obsolete, now divided into Carina, Vela, and Puppis)[30]

- Pyxis Nautica (full name of Pyxis)[31]

In addition, Mons Mænalus is shown below Boötes, Caput Medusæ is shown as part of Perseus, and Cerberus is shown with Hercules.[2]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Advertisement". Monthly Critical Gazette. London: Sherwood, Jones, and Co. December 1824. p. 578. See also File:Advertisement for Urania's Mirror.png.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Ridpath, Ian. "Urania's Mirror". Ian Ridpath's Old Star Atlases. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Hingley, P. D. (1994). "Urania's Mirror — A 170-year old mystery solved?". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 104 (5): 238–40. Bibcode:1994JBAA..104..238H. p. 239

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Hingley, P. D. (1994). "Urania's Mirror — A 170-year old mystery solved?". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 104 (5): 238–40. Bibcode:1994JBAA..104..238H. p. 238

- ↑ Hingley, P. D. (1994). "Urania's Mirror — A 170-year old mystery solved?". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 104 (5): 238–40. Bibcode:1994JBAA..104..238H. p. 239 (illus.)

- ↑ Hingley, P. D. (1994). "Urania's Mirror — A 170-year old mystery solved?". Journal of the British Astronomical Association. 104 (5): 238–40. Bibcode:1994JBAA..104..238H. p. 240

- ↑ Taken from the reproduction of the book included in the 2004 Barnes and Noble facsimile edition of the Urania's Mirror set.

- ↑ "[Advertisement]". The Quarterly Literary Advertiser (Part of The Quarterly Literary Journal). Duke-Street, Picadilly, London: John Sharpe. October 1828: 17. 1828. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ An obsolete plural form of the name of the constellation Triangulum

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Rangifer". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Custos Messium". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Honores Friderici". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Telescopium Herschilii". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Quadrans Muralis". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Taurus Poniatovii". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Scutum". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Antinous". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Vulpecula". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Musca Borealis". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Globus Aerostaticus". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Harpa Georgii". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Hill, John (1754). "Fluvius". Urania: Or, a Compleat View of the Heavens; Containing the Antient and Modern Astronomy, in Form of a Dictionary: Illustrated with a Great Number of Figures ... A Work Intended for General Use, Intelligible to All Capacities, and Calculated for Entertainment as Well as Instruction. London: T. Gardner. p. [unpaginated].

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Machina Electrica". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Hill, John (1754). "Pigeon". Urania: Or, a Compleat View of the Heavens; Containing the Antient and Modern Astronomy, in Form of a Dictionary: Illustrated with a Great Number of Figures ... A Work Intended for General Use, Intelligible to All Capacities, and Calculated for Entertainment as Well as Instruction. London: T. Gardner. p. [unpaginated].

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Officina Typographica". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Turdus Solitarius". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Sextans". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Felis". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Antlia". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Argo Navis". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Pyxis". Star Tales. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Urania's Mirror. |

- "Urania's Mirror". Treasures of the RAS. Royal Astronomical Society. Includes a video presentation of the cards.

.jpg)