United States v. Washington

| United States v. Washington | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit |

| Decided |

June 4 1975 Full name

|

| Citation(s) | 520 F.2d 676 |

| Case history | |

| Prior action(s) | 384 F.Supp. 312 |

| Subsequent action(s) | certiorari denied by 423 U.S. 1086 (1976) |

| Holding | |

| "[The] state could regulate fishing rights guaranteed to the Indians only to the extent necessary to preserve a particular species in a particular run; that trial court did not abuse its discretion in apportioning the opportunity to catch fish between whites and Indians on a 50-50 basis; that trial court properly excluded Indians' catch on their reservations from apportionment; and that certain tribes were properly recognized as descendants of treaty signatories and thus entitled to rights under the treaties. [Affirmed and remanded]." | |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Herbert Choy, Alfred Goodwin, and District Judge James M. Burns (sitting by designation) |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Choy |

| Concurrence | Burns |

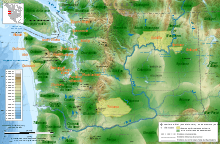

United States v. Washington, 384 F. Supp. 312 (W.D. Wash. 1974), aff'd, 520 F.2d 676 (9th Cir. 1975), commonly known as the Boldt Decision (from the name of the trial court judge, George Hugo Boldt), was a 1974 case heard in the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington and the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. It reaffirmed the reserved right of American Indian tribes in the State of Washington to act alongside the state as co-managers of salmon and other fish, and to continue harvesting them in accordance with the various treaties that the United States had signed with the tribes. The tribes of Washington had ceded their land to the United States but had reserved the right to fish as they had always done, including fishing at their traditional locations that were off the designated reservations.

Over time, the state of Washington had infringed on the treaty rights of the tribes despite losing a series of court cases on the issue. Those cases provided the Indians a right of access through private property to their fishing locations, and said that the state could neither charge Indians a fee to fish nor discriminate against the tribes in the method of fishing allowed. Those cases also provided for the Indians' rights to a fair and equitable share of the harvest. The Boldt decision further defined that reserved right, holding that the tribes were entitled to half the fish harvest each year.

In 1975 the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Judge Boldt's ruling. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case. After the state refused to enforce the court order, Judge Boldt ordered the United States Coast Guard and federal law enforcement agencies to enforce his rulings. On July 2, 1979, the Supreme Court rejected a collateral attack[fn 1] on the case, largely endorsing Judge Boldt's ruling and the opinion of the Ninth Circuit. In Washington v. Washington State Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Ass'n, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote that "[b]oth sides have a right, secured by treaty, to take a fair share of the available fish."[1] The Supreme Court also endorsed Boldt's orders to enforce his rulings by the use of federal law enforcement assets and the Coast Guard.

Background

History of tribal fishing

The American Indians of the Pacific Northwest had long depended on the salmon harvest, a resource which allowed them to become the wealthiest North American tribes.[2] The salmon harvest for the Columbia River basin was estimated at 43,000,000 pounds (20,000,000 kg) annually,[3] which not only provided sufficient salmon for the tribes' needs, but also enough to trade with others.[fn 2] By the 1840s, tribes were trading salmon to the Hudson Bay Company which shipped the fish to New York, Great Britain, and other locations around the world.[6]

Treaties

In the 1850s, the United States government entered into a series of treaties with the American Indian tribes of the Pacific Northwest. In the Treaty of Olympia,[7] territorial governor Isaac I. Stevens[fn 3] agreed that the tribes had rights including:

"The right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations is secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the Territory, and of erecting temporary houses for the purpose of curing the same; together with the privilege of hunting, gathering roots and berries, and pasturing their horses on all open and unclaimed lands. Provided, however, That they shall not take shell-fish from any beds staked or cultivated by citizens; and provided, also, that they shall alter all stallions not intended for breeding, and keep up and confine the stallions themselves."[9]

Other agreements with area tribes included the treaties of Medicine Creek,[10] Point Elliott,[11] Neah Bay,[12] and Point No Point.[13] All of these had similar language on the rights of the Indians to fish outside the reservation.[14] While the tribes agreed to part with their land, they insisted on protecting their fishing rights throughout the Washington territory.[15]

Post-treaty history

Initially, the federal government honored its treaties with the tribes, but with increasing numbers of white settlers moving into the area, the settlers began to infringe upon the fishing rights of the native tribes. By 1883, whites had established more than forty salmon canneries.[16] In 1894, there were three canneries in the Puget Sound area; by 1905 there were twenty-four.[17] The whites also began to use new techniques that prevented a significant portion of the salmon from reaching the tribal fishing areas.[18] When Washington Territory became a state in 1889, the legislature passed "laws to curtail tribal fishing in the name of 'conservation' but what some scholars described as being designed to protect white fisheries".[fn 4][20] The state legislature, by 1897, had banned the use of weirs, which were customarily used by Indians.[21] The tribes turned to the courts for enforcement of their rights under the treaties.[22]

United States v. Taylor

In one of the earliest of these enforcement cases,[23] decided in 1887, the United States Indian Agent and several members of the Yakima tribe filed suit in territorial court to enforce their right of access to off-reservation fishing locations. Frank Taylor, a non-Indian settler, had obtained land from the United States and had fenced off the land, preventing access by the Yakima to their traditional fishing locations.[24] Although the trial court[fn 5] ruled in Taylor's favor, the Supreme Court of the Territory of Washington reversed[26] and held that the tribe had reserved its own rights to fish, thereby creating an easement or an equitable servitude of the land that was not extinguished when Taylor obtained title.[fn 6][28]

United States v. Winans

Within ten years, another case arose,[29] which dealt with fishing rights at Celilo Falls, a traditional Indian fishing location. Two brothers, Lineas and Audubon Winans, owned property on both sides of the Columbia River and obtained licenses from the state of Washington to operate four fish wheels.[30] The wheels prevented a significant number of salmon from passing the location. Additionally, the Winans prohibited anyone, whether an Indian with treaty rights or otherwise, from crossing their land to get to the falls.[31]

The United States Attorney for Washington then filed a suit to enforce the treaty rights of the tribe.[fn 7] The trial court held that the property rights of the Winans allowed them to exclude others from the property, including the Indians.[33] In 1905, the United States Supreme Court reversed that decision, holding that the tribe had reserved fishing rights when they ceded the property to the United States.[34] Since the tribes had the right to fish reserved in the treaties, the federal government and subsequent owners had no greater property rights than were granted by the treaties.[35]

Seufert Bros. Co. v. United States

In 1914, the United States sued again,[36] this time against the Seufert Brothers Company which had prevented Yakima Indians including Sam Williams from fishing on the Oregon side of the Columbia River near the Celilo Falls.[37] After the United States sued on behalf of Williams, the United States District Court in Oregon issued an injunction which the Supreme Court affirmed, again holding that the treaties created a servitude that ran with the land.[38] This decision was significant in that it expanded the hunting and fishing rights outside the territory ceded by the tribes when it was shown that the tribe used the area for hunting and fishing.[39]

State attempts to regulate Indian fishing

Tulee v. Washington

In Tulee v. Washington,[40] the United States Supreme Court once again ruled on the treaty rights of the Yakima tribe. In 1939, Sampson Tulee, a Yakima, was arrested for fishing without a state fishing license.[fn 8][42] The United States government immediately filed for a writ of habeas corpus on Tulee's behalf, which was denied on procedural grounds because he had not yet been tried in state court and had not exhausted his appeals.[43] Tulee was convicted in state court, which was upheld by the Washington Supreme Court on the grounds that the state's sovereignty allowed it to impose a fee on Indians who were fishing outside the reservation.[44] The United States Supreme Court reversed, stating "we are of the opinion that the state is without power to charge the Yakimas a fee for fishing".[45]

The Puyallup cases

Following the Tulee decision, there were three United States Supreme Court decisions involving the Puyallup tribe.[fn 9] The first was Puyallup Tribe v. Department of Game of Washington, (Puyallup I)[fn 10][47] which involved a state ban on the use of nets to catch steelhead trout and salmon.[fn 11] Despite the ban, the tribes continued to use nets based on their treaty rights.[49] Justice William Douglas delivered the opinion of the Court which said that the treaty did not prevent state regulations that were reasonable and necessary under a fish conservation scheme, provided the regulation was not discriminatory.[50]

After being remanded to determine if the regulations were not discriminatory, the case returned to the United States Supreme Court in Department of Game of Washington v. Puyallup Tribe (Puyallyp II).[51] Again, Justice Douglas wrote the opinion for the Court, but this time he struck down the state restrictions as discriminatory.[52] Douglas noted that the restrictions for catching steelhead trout with nets had remained, and was a method used only by the Indians, whereas hook and line fishing was allowed but was used only by non-Indians.[53] As such, the effect of the regulation allocated all of the steelhead trout fishing to sport anglers, and none to the tribes.[54]

The third case, Puyallup Tribe, Inc. v. Department of Game of Washington (Puyallup III),[55] was decided in 1977. Members of the Puyallup Tribe filed suit, arguing that under the doctrine of sovereign immunity, Washington state courts lacked jurisdiction to regulate fishing activities on tribal reservations.[56] Writing for a majority of the Court, Justice John Paul Stevens held that, despite the tribe's sovereign immunity, the state could regulate the harvest of steelhead trout in the portion of the river that ran through the Puyallup Reservation as long as the state could base its decision and apportionment on conservation grounds.[57]

The Belloni decision

One year after the Puyallup I decision, Judge Robert C. Belloni issued an order in Sohappy v. Smith,[58] a treaty fishing case involving the Yakima tribe and the state of Oregon. In this case, Oregon had discriminated against the Indians in favor of sports and commercial fishermen, allocating almost nothing to the tribes at the headwaters of the river.[59] Oregon argued that the treaties only gave the Indians the same rights as every other citizen, and Belloni noted that "[s]uch a reading would not seem unreasonable if all history, anthropology, biology, prior case law and the intention of the parties to the treaty were to be ignored".[60] Belloni also found that:

The state may regulate fishing by non-Indians to achieve a wide variety of management or "conservation" objectives. Its selection of regulations to achieve these objectives is limited only by its own organic law and the standards of reasonableness required by the Fourteenth Amendment. But when it is regulating the federal right of Indians to take fish at their usual and accustomed places it does not have the same latitude in prescribing the management objectives and the regulatory means of achieving them. The state may not qualify the federal right by subordinating it to some other state objective or policy. It may use its police power only to the extent necessary to prevent the exercise of that right in a manner that will imperil the continued existence of the fish resource.[61]

Belloni issued a final ruling that the tribes were entitled to a fair and equitable portion of the fish harvest.[62] The court retained continuing jurisdiction,[fn 12] and his order was not appealed.[64]

U.S. District Court (Boldt decision)

Issue

Although the Belloni decision established the rights of the Indians to exercise their treaty fishing rights, the states of Oregon and Washington continued to arrest Indians for violations of state law and regulations that infringed on those rights.[65] In September 1970, the United States Attorney filed an action in the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington alleging that the state of Washington had infringed on the treaty rights of the Hoh, Makah, Muckleshoot, Nisqually, Puyallup, Quileute, and Skokomish tribes.[66] Later, the Lummi, Quinault, Sauk-Suiattle, Squaxin Island, Stillaguamish, Upper Skagit, and Yakima tribes intervened in the case.[67] Defendants were the state of Washington, the Washington Department of Fisheries, the Washington Game Commission, and the Washington Reef Net Owners Association.

Trial

The first phase of the case took three years, mainly in preparation for trial.[68] During the trial, Boldt heard testimony from about fifty witnesses and admitted 350 exhibits.[69] The evidence showed that the state had shut down many sites used by Indians for net fishing while allowing commercial net fishing elsewhere on the same run.[70] At most, the tribes took only about two percent (2%) of the total harvest.[71] There was no evidence presented by the state that showed any detrimental actions by Indians toward the harvest.[72] Both expert testimony and cultural testimony was presented, with tribal members relating the oral history dealing with the treaties and fishing rights.[73] Additionally, Boldt found that the tribe's witnesses were more credible than those of the state, finding that the tribe's expert witnesses were "exceptionally well researched".[74]

Holding

The court held that, when the tribes conveyed millions of acres of land in Washington State through a series of treaties signed in 1854 and 1855, they reserved the right to continue fishing. The court looked at the minutes of the treaty negotiations to interpret the meaning of the treaty language "in common with"[fn 13] as the United States described it to the Tribes, holding that the United States intended for there to be an equal sharing of the fish resource between the Tribes and the settlers.[75] As the court stated, the phrase means "sharing equally the opportunity to take fish ... therefore, nontreaty fishermen shall have the opportunity to take up to 50% of the harvestable number of fish ... and treaty right fishermen shall have the opportunity to take up to the same percentage".[76] The formula used by Boldt gave the tribes forty-three percent (43%) of the Puget Sound harvest, which was equivalent to eighteen percent (18%) of the statewide harvest.[fn 14][78] The order required the state to limit the amount of fish taken by non-Indian commercial fishermen, causing a drop in their income from about $15,000–20,000 to $500-2,000.[79]

Furthermore, the court also held the state could regulate the Indians' exercise of their treaty rights, but only to ensure the "perpetuation of a run or of a species of fish".[80] To regulate the Indians, the state must be able to show that conservation could not be achieved by regulating only the non-Indians, must not discriminate against the Indians, and must use appropriate due process.[81]

Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals

Opinion of the court

After the District Court issued its ruling, both sides submitted appeals to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.[82] Washington argued that the district court had no power to invalidate state fishing regulations, while the tribes argued "the state may not regulate their fishing activities at treaty locations for any reason".[83] Writing for a majority of the court, Circuit Court Judge Herbert Choy affirmed Judge Boldt's opinion "in all respects", but clarified that Judge Boldt's "equitable apportionment" of harvestable fish did not apply to "fish caught by non-Washington citizens outside the state's jurisdiction".[84]

In his majority opinion, Judge Choy emphasized that states may not enact regulations that are "in conflict with treaties in force between the United States and the Indian nations".[85] Consequently, he concluded that the treaties signed in the 1850s expressly preempted Washington's regulations and that non-Indians had "only a limited right to fish at treaty places."[86] Judge Choy also emphasized that the tribes were "entitled to an equitable apportionment of the opportunity to fish in order to safeguard their federal treaty rights" and that the Ninth Circuit should grant the district court a "great amount of discretion as a court of equity" when apportioning rights to fisheries.[87] He held that the district court's apportionment "was well within its discretion", but clarified that tribes were not entitled to compensation for "unanticipated heavy fishing" that occurred off Washington's coast.[88] Judge Choy also clarified that the district court's equitable remedy should attempt to minimize hardships for white reef net fishermen.[89]

Concurrence

District court judge James M. Burns, sitting by designation, wrote a separate concurring opinion in which he criticized the "recalcitrance of Washington State officials" in their management of the state's fisheries.[90] Judge Burns argued that Washington's recalcitrance forced Judge Boldt to act as "perpetual fishmaster" and noted that he "deplore[d]" situations in which district court judges are forced to act as "enduring managers of the fisheries, forests, and highways".[91] In his concluding remarks, Judge Burns argued that Washington's responsibility to manage its natural resources "should neither escape notice nor be forgotten."[92]

Certiorari denied

After the Ninth Circuit issued its ruling in the direct appeal, the case was remanded to the district court for further proceedings.[93] Washington submitted an appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States, but the Supreme Court denied the state's petition for certiorari and subsequent petition for rehearing.[94] Despite these rulings, the parties in the original case continued to litigate issues relating to apportionment of the fisheries and subsequent rulings have been issued as recently as May 2015.[95]

Subsequent developments

Legal

Collateral attacks

After Boldt's decision, the Washington Department of Fisheries issued new regulations in compliance with the decision.[96] The Puget Sound Gillnetters Association and the Washington State Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Association both filed lawsuits in state court to block the new regulations.[97] These private concerns won at both the trial court[fn 15] and at the Washington Supreme Court.[99] Washington Attorney General Slade Gorton, representing the state of Washington, supported the position of the private concerns and opposed the position of the United States and the tribes.[100] The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari and vacated the decision of the Washington Supreme Court.[101]

Justice John Paul Stevens announced the decision of the Court, which upheld Judge Boldt's order and overturned the rulings of the state courts.[102] Stevens made it explicitly clear that Boldt could issue the orders he did, stating "[t]he federal court unquestionably has the power to enter the various orders that state official and private parties have chosen to ignore, and even to displace local enforcement of those orders if necessary to remedy the violations of federal law found by the court."[fn 16][104]

Court supervision

When the state would not enforce his order to reduce the catch of non-Indian commercial fishermen, Boldt took direct action, placing the matter under federal supervision.[105] The United States Coast Guard and the National Marine Fisheries Service were ordered to enforce the ruling and soon had boats in the water confronting violators.[106] Some of the protesters rammed Coast Guard boats and at least one member of the Coast Guard was shot.[107] Those whom the officers caught breaking the court's orders were taken before federal magistrates and fined for contempt, and the illegal fishing as a protest stopped.[108] The United States District Court continued to exercise jurisdiction over the matter, determining traditional fishing locations[109] and compiling major orders of the court.[110]

Phase II

The case continued to have issues brought up before the district court. In what became known as "Phase II",[111] District Judge William H. Orrick, Jr. heard the issues presented by the United States on behalf of the tribes. Following the hearing, Orrick enjoined the state of Washington from damaging the fishes' habitat, and included hatchery-raised fish in the allocation to Indians.[112] The state of Washington appealed the decision to the Ninth Circuit, which affirmed in part and reversed in part, allowing the hatchery fish to remain in the allocation, but leaving the habitat issue open.[113]

Culvert case subproceeding

In 2001, twenty-one northwest Washington tribes, joined by the United States filed a Request for Determination in U.S. District Court, asking the court to find that the State of Washington has a treaty-based duty to preserve fish runs and habitat sufficiently for the tribes to earn a “moderate living,” and sought to compel the state to repair or replace culverts that impede salmon migration. On August 22, 2007, the district court issued a summary judgment order, holding that while culverts impeding andromadous fish migration are not the only factor diminishing their upstream habitat, in building and maintaining culverts that impede salmon migration, Washington State had diminished the size of salmon runs within the case area and thereby violated its obligation under the Stevens Treaties. On March 29, 2013, the court issued an injunction ordering the state to significantly increase the effort for removing state-owned culverts that block habitat for salmon and steelhead, and to replace the state-owned culverts that have the greatest adverse impact on the habitat of andromadous fish by 2030.

The State of Washington appealed the district court’s decision to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. On June 27, 2016, a three judge panel of the Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision and upheld the injunction. Washington State has estimated it will need to fix an average of 30 to 40 culverts a year to comply with the injunction.[114]

Public response

Scholars consider the Boldt decision to be a landmark case in American Indian law, in the area of cooperative management of resources,[115] for Indian treaty rights,[116] internationally for aboriginal treaty rights,[117] and tribal civil rights.[118]

The decision caused an immediate negative reaction from some citizens of Washington. Bumper stickers reading "Can Judge Boldt, Not Salmon" appeared, and Boldt was hung in effigy at the federal courthouse.[119] Non-Indian commercial fishermen ignored the ruling and the state was reluctant (or at times refused) to enforce the law.[fn 17][122] By 1978, Congressman John E. Cunningham tried to get a bill passed to abrogate the treaties, to break up Indian holdings, and stop giving the tribes "special consideration", but the effort failed.[123] In 1984, Washington voters passed an initiative ending "special rights" for Indians,[124] but the state refused to enforce it as being preempted by federal law.[125]

United States v. Washington was a landmark case in terms of Native American civil rights and evoked strong emotions. According to former U.S. Representative Lloyd Meeds of Everett, "the fishing issue was to Washington state what busing was to the East" for African Americans during the Civil Rights Movement.[126]

Tribal developments

The tribes involved benefited greatly from the decision. Prior to Boldt's ruling, Indians collected less than five percent (5%) of the harvest, but by 1984, they were collecting forty-nine percent (49%).[127] Tribal members became successful commercial fishermen, even expanding to marine fishing as far away as Alaska.[128] The tribes became co-managers of the fisheries along with the state, hiring fish biologists and staff to carry out those duties.[129] The Makah tribe, based on the terms of the Neah Bay Treaty and the Boldt decision, took their first California gray whale in over seventy years in 1999.[130] Following a lawsuit by various animal rights activists, the tribe was allocated the right to take up to five whales a year for the 2001 and 2002 seasons.[131]

Notes

- ↑ A collateral attack is an indirect method of attempting to overturn a previous decision on procedural or jurisdictional grounds.

- ↑ Meriwether Lewis and William Clark observed "over one hundred fishing stations" along the Columbia river alone.[4] Clark wrote that the river "was crowded with salmon".[5]

- ↑ Stevens was the first territorial governor of the Washington Territory, and both he and Joel Palmer (territorial governor of Oregon) negotiated nine treaties.[8]

- ↑ Scholars included law professors such as Michael C. Blumm of Lewis & Clark Law School and Brett M. Swift of the University of Colorado School of Law.[19]

- ↑ The trial court was the Fourth Judicial District Court of the Territory of Washington.[25]

- ↑ The territorial Supreme Court also noted that any Indian treaty was to be construed in the favor of the Indians.[27]

- ↑ Federal law imposes a duty on the United States Attorney to represent Indian tribes in lawsuits.[32]

- ↑ The issue appears to be that Tulee was using a dip net and was selling his catch. Fishing with a line and hook did not require a license.[41]

- ↑ These cases also involved civil disobedience by members of the tribes and others. Actor Marlon Brando was arrested with tribal leader Robert Satiacum during a fishing protest. So was comedian Dick Gregory (who then conducted a 39-day hunger strike).[46]

- ↑ The decisions were known as Puyallup I, Puyallup II, and Puyallup III.

- ↑ The tribe harvested Chinook, Coho (or silver), Chum, and pink salmon, in addition to the steelhead trout.[48]

- ↑ "The rule that a court retains power to enter and enforce a judgment over a party even though that party is no longer subject to a new action."[63]

- ↑ "In common with" is a legal term of art, indicating joint ownership of the property or resource, in this case the salmon and other fish.

- ↑ "Judge Boldt excluded from this equal sharing formula fish harvested by tribes on reservations, fish not destined to pass the tribe's historic fishing sites, and fish caught outside Washington waters, even if they were bound for the tribe's fishing grounds."[77]

- ↑ The Thurston County Superior Court had held that the regulations were adopted due to the federal court ruling and had no basis in state law. The regulations were invalidated on those and other grounds.[98]

- ↑ Stevens went to the point of quoting the Ninth Circuit's comments condemning the actions of the state of Washington, which said:

The state's extraordinary machinations in resisting the [1974] decree have forced the district court to take over a large share of the management of the state's fishery in order to enforce its decrees. Except for some desegregation cases . . ., the district court has faced the most concerted official and private efforts to frustrate a decree of a federal court witnessed in this century. The challenged orders in this appeal must be reviewed by this court in the context of events forced by litigants who offered the court no reasonable choice.[103]

- ↑ It was alleged that Gorton's failure to support enforcement of Boldt's order led to the complete breakdown of law enforcement on state waters in Washington.[120] Additionally, local prosecutors and state judges routinely dismissed any criminal charges against the non-Indian fishermen.[121]

References

- ↑ Washington v. Washington State Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Ass'n, 443 U.S. 658, 684–85 (1979).

- ↑ Michael C. Blumm and Brett M. Swift, The Indian Treaty Piscary Profit and Habitat Protection in the Pacific Northwest: A Property Rights Approach, 69 U. Colo. L. Rev. 407, 421 (1998).

- ↑ Blumm, at 421.

- ↑ Blumm, at 421.

- ↑ Charles F. Wilkinson, Crossing the Next Meridian: Land, Water, and the Future of the West 184 (1992) (hereinafter cited as Meridian).

- ↑ Blumm, at 424.

- ↑ Treaty of Olympia, July 1, 1855, and Jan. 25, 1856, ratified Mar. 8, 1859, 12 Stat. 971; 2 Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties 719, (Charles J. Kappler, ed. 1904).

- ↑ Meridian, at 186–87; Blumm, at 428.

- ↑ Treaty of Olympia; Kappler, at 719.

- ↑ Treaty of Medicine Creek, Dec. 26, 1854, ratified Mar. 3, 1855, 10 Stat. 1132; Kappler, at 661.

- ↑ Treaty of Point Elliot, Jan. 22, 1855, ratified Mar. 8, 1859, 12 Stat. 927; Kappler, at 669.

- ↑ Treaty of Neah Bay, Jan. 31, 1855, ratified Mar. 8, 1859, 12 Stat. 939; Kappler, at 682.

- ↑ Treaty of Point No Point, Jan. 26, 1855, ratified Mar. 8, 1859, 12 Stat. 933; Kappler, at 664.

- ↑ Boldt decision, 384 F. Supp. at 331; Meridian, at 186–87.

- ↑ Meridian, at 186–87; Alvin J. Ziontz, A Lawyer in Indian Country: A Memoir 83 (2009); Blumm, at 430.

- ↑ Blumm, at 434.

- ↑ Ziontz, at 84; Blumm, at 430.

- ↑ Blumm, at 434 ("Whites also effectively preempted upriver tribal fisheries by securing a locational advantage. . .").

- ↑ Blumm, at n.a1 & n.aa1, 401.

- ↑ Blumm, at 435; see generally Ziontz, at 85.

- ↑ Fronda Woods, Who's in Charge of Fishing?, 106 Ore. Hist. Q. 412, 415 (2005).

- ↑ Blumm, at 435.

- ↑ United States v. Taylor, 13 P. 333 (Wash. Terr. 1887).

- ↑ Paul C. Rosier, Native American Issues 33 (2003); Blumm, at 436; Vincent Mulier, Recognizing the Full Scope of the Right to Take Fish under the Stevens Treaties: The History of Fishing Rights Litigation in the Pacific Northwest, 31 Am. Indian L. Rev. 41, 44–45 (2006–2007).

- ↑ Mulier, at 44–45.

- ↑ Rosier, at 33; Mulier, at 45.

- ↑ Taylor, 13 P. at 333; Blumm, at 436.

- ↑ Taylor, 13 P. at 336; Blumm, at 436–38; Mulier, at 46.

- ↑ United States v. Winans, 198 U.S. 371 (1905).

- ↑ Blumm, at 440; Mulier, at 46.

- ↑ Blumm, at 440; Mulier, at 46.

- ↑ 25 U.S.C. § 175; Solicitor for the Interior Department, Handbook of Federal Indian law 253 (1942).

- ↑ Blumm, at 440; Mulier, at 47.

- ↑ Winans, 198 U.S. at 371; Rosier, at 33; Blumm, at 441.

- ↑ Winans, 198 U.S. at 381; Blumm, at 442–43; Mulier, at 48.

- ↑ Seufert Bros. Co. v. United States, 249 U.S. 194 (1919).

- ↑ Seufert Bros. Co., 249 U.S. at 195; Blumm, at 446.

- ↑ Seufert Bros., 249 U.S. at 199; Blumm, at 447.

- ↑ Blumm, at 440; Mulier, at 50.

- ↑ Tulee v. Washington, 315 U.S. 681 (1942) (hereinafter cited as Tulee III).

- ↑ State v. Tulee, 109 P.2d 280 (Wash. 1941) (hereinafter cited as Tulee II).

- ↑ Tulee II, 109 P.2d at 280; Ziontz, at 85.

- ↑ United States in Behalf of Tulee v. House, 110 F.2d 797, 798 (9th Cir. 1940) (hereinafter cited as Tulee I).

- ↑ Tulee II, 109 P.2d at 141; Blumm, at 448.

- ↑ Tulee III, 315 U.S. at 685; see generally Ziontz, at 85; Blumm, at 448–49.

- ↑ Rosier, at 33.

- ↑ Puyallup Tribe v. Dept. of Game of Washington, 391 U.S. 392 (1968) (hereinafter cited as Puyallup I).

- ↑ Puyallup I, 391 U.S. at 395.

- ↑ Puyallap I, 391 U.S. at 396; Blumm, at 449.

- ↑ Puyallap I, 391 U.S. at 398; Blumm, at 449–50.

- ↑ Dept. of Game of Washington v. Puyallup Tribe, 414 U.S. 14 (1973) (hereinafter cited as Puyallup II).

- ↑ Puyallup II, 414 U.S. at 48; Blumm, at 451.

- ↑ Mulier, at 52.

- ↑ Puyallup II, 414 U.S. at 48; Michael J. Bean & Melanie J. Rowland, The Evolution of National Wildlife Law 453-54 (1997); Blumm, at 451; Mulier, at 52.

- ↑ Puyallup Tribe, Inc. v. Dept. of Game of Washington, 433 U.S. 165 (1977) (hereinafter cited as Puyallup III).

- ↑ Puyallup III, 433 U.S. at 167-68.

- ↑ Puyallup III, 433 U.S. at 177–78; Bean, at 455; Blumm, at 451.

- ↑ Sohappy v. Smith, 302 F. Supp. 899 (D. Ore. 1969); Blumm, at 453–54.

- ↑ Sohappy, 302 F. Supp. at 911; Ziontz, at 90–91; Blumm, at 454; Mulier, at 54–55.

- ↑ Sohappy, 302 F. Supp. at 905; Mulier, at 55.

- ↑ Sohappy, 302 F. Supp. at 908; Mulier, at 56–57.

- ↑ Mulier, at 58.

- ↑ CONTINUING-JURISDICTION DOCTRINE, Black's Law Dictionary (10th ed. 2014).

- ↑ Mulier, at 58.

- ↑ Blumm, at 455.

- ↑ Boldt decision, 384 F. Supp. at n.1 327; Meridian, at 206; Ziontz, at 95.

- ↑ Boldt decision, 384 F. Supp. at n.2 327; see also Rosier, at 35; Ziontz, at 95.

- ↑ Mulier, at 59.

- ↑ Charles F. Wilkinson, Blood Struggle: The Rise of Modern Indian Nations 200 (2005) (hereinafter cited as Wilkinson); Meridian, at 206.

- ↑ Blumm, at 455.

- ↑ Blumm, at 455.

- ↑ Blumm, at 455.

- ↑ Wilkinson, at 201.

- ↑ Wilkinson, at 200–01.

- ↑ Bean, at 457; Meridian, at 206; Ziontz, at 123.

- ↑ Boldt decision, 384 F. Supp. at 343; Bean, at 457; Wilkinson, at 202; Mulier, at 61; see generally Blumm, at 456.

- ↑ Blumm, at 456.

- ↑ Blumm, at 456.

- ↑ David Ammons, Court Ruling Gives Indians Their Biggest Victory Since "Last Stand", Santa Cruz Sentinel (Cal.), Dec. 29, 1974, at 7 (via Newspapers.com

).

). - ↑ United States v. Washington, 520 F.2d 676, 683 (9th Cir. 1975); Bean, at 457.

- ↑ Washington, 520 F.2d at 683; Bean, at 457; Mulier, at 66–67.

- ↑ United States v. Washington, 520 F.2d 676, 682 (9th Cir. 1975).

- ↑ Washington, 520 F.2d at 682 n.2, 684.

- ↑ Washington, 520 F.2d at 688-90, 693.

- ↑ Washington, 520 F.2d at 685 (noting that "the Indians negotiated the treaties as at least quasi-sovereign nations").

- ↑ Washington, 520 F.2d at 685.

- ↑ Washington, 520 F.2d at 687.

- ↑ Washington, 520 F.2d at 687.

- ↑ Washington, 520 F.2d at 691-92.

- ↑ Washington, 520 F.2d at 693 (Burns, J., concurring).

- ↑ Washington, 520 F.2d at 693 (Burns, J., concurring) (internal quotations omitted).

- ↑ Washington, 520 F.2d at 693 (Burns, J., concurring); Mary Christina Wood, The Tribal Property Right to Wildlife Capital (Part II): Asserting a Sovereign Servitude to Protect Habitat of Imperiled Species, 25 Vt. L. Rev. 355, 419 (2001) (discussing Judge Burns' criticisms of judges acting as "fishmasters"); Michael C. Blumm & Jane G. Steadman, Indian Treaty Fishing Rights and Habitat Protection: The Martinez Decision Supplies a Resounding Judicial Reaffirmation, 49 Nat. Resources J. 653, 699 n.273 (2009) (discussing Judge Burns' criticism of state officials).

- ↑ Washington, 520 F.2d at 693.

- ↑ Washington v. United States, 423 U.S. 1086 (1976) (denying certiorari); Washington v. United States, 424 U.S. 978 (1976) (denying rehearing).

- ↑ United States v. Washington, No. C70-9213, Subproceding 89-3-09, 2015 WL 3451316 (W.D. Wash. May 29, 2015). For examples of further litigation in the Ninth Circuit, see, e.g., United States v. Washington, 573 F.3d 701 (9th Cir. 2009); United States v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 901 F.2d 772, 773 (9th Cir. 1990); United States v. Washington, 730 F.2d 1314 (9th Cir. 1984).

- ↑ Bean, at 457.

- ↑ Fishing Vessel Ass'n, 443 U.S. at 672; Bean, at 457; Ziontz, at 125.

- ↑ Washington State Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Ass'n v. Tollefson, 553 P.2d 113, 114 (Wash. 1976); Matthew Deisen, State v. Jim: A New Era in Washington's Treatment of the Tribe?, 39 Am. Indian L. Rev. 101, 121 (2013–2014).

- ↑ Fishing Vessel Ass'n, 443 U.S. at 672; Bean, at 457.

- ↑ Meridian, at 207.

- ↑ Fishing Vessel Ass'n, 443 U.S. at 696.

- ↑ Fishing Vessel Ass'n, 443 U.S. at 696; Bean, at 459; Rosier, at 36.

- ↑ Fishing Vessel Ass'n, 443 U.S. at n.36 696; Wilkinson, at 203; Ziontz, at 128.

- ↑ Fishing Vessel Ass'n, 443 U.S. at 695–96; see generally Rosier, at 36.

- ↑ Ziontz, at 126; Deisen, at 121; Mulier, at 70.

- ↑ Ziontz, at 126.

- ↑ Bruce Elliott Johansen, Native Americans Today: A Biographical Dictionary 28 (2010).

- ↑ Ziontz, at 126; Mulier, at 70.

- ↑ United States v. Washington, No. C70-9213RSM, 2013 WL 6328825 (W.D. Wash. Dec. 5, 2013).

- ↑ United States v. Washington, 20 F.Supp.3d 986 (W.D. Wash. 2013).

- ↑ United States v. Washington, 506 F. Supp. 187, 191 (W.D. Wash. 1980), aff'd in part, rev'd in part by 694 F.2d 1374 (9th Cir. 1983); Peter C. Monson, United States v. Washington (Phase II): The Indian Fishing Conflict Moves Upstream, 12 Envtl. L. 469 (1982).

- ↑ Washington, 506 F. Supp. at 200-01; Monson, at 486.

- ↑ Mulier, at 81-82.

- ↑ Terryl Asla, Culvert replacements: Kingston area faces a summer of detours, Kingston Community News (Wash.), Apr. 14, 2016; Jeremiah O'Hagan, SR 532 to close for culvert replacement, Stanwood Camano News (Wash.), July 27, 2016.

- ↑ Syma A. Ebbin, Dividing the Waters: Cooperative Management and the Allocation of Pacific Salmon in The Tribes and the States: Geographies of Intergovernmental Interaction 159, 166 (Brad A. Bays & Erin Hogan Fouberg, eds. 2002).

- ↑ Documents of United States Indian Policy 268 (Francis Paul Prucha, ed. 2000).

- ↑ Frank Cassidy & Norman Dale, After Native Claims?: The Implications of Comprehensive Claims Settlements for Natural Resources in British Columbia 65 (1988).

- ↑ Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West 333 (2011).

- ↑ Rosier, at 35; Meridian, at 206; Wilkinson, at 203.

- ↑ Ziontz, at 128.

- ↑ Mulier, at 68.

- ↑ Meridian, at 207; Rosier, at 35; Ziontz, at 125; Mulier, at 68.

- ↑ Rosier, at 40.

- ↑ Wash. Rev. Code § 77.110.010 et seq., Initiative Measure No. 456, approved November 6, 1984.

- ↑ Rosier, at 40.

- ↑ Alex Tizon, The Boldt Decision / 25 Years – The Fish Tale That Changed History, Seattle Times, Feb. 7, 1999.

- ↑ Rosier, at 35; Ziontz, at 131.

- ↑ Ziontz, at 129.

- ↑ Ziontz, at 129.

- ↑ Robert J. Miller, Exercising Cultural Self-Determination: The Makah Indian Tribe Goes Whaling, 25 Am. Indian L. Rev. 165, 167 (2000–2001).

- ↑ Miller, at n.3 167.

Further reading

- Text of the Boldt Decision: Hon. George H. Boldt, The Boldt Decision; PDF on the site of the Washington (state) Department of Fish and Wildlife