Uchchaihshravas

| Uchchaihshravas | |

|---|---|

Uchchaihshravas |

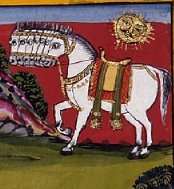

In Hindu mythology, Uchchaihshravas (Sanskrit: उच्चैःश्रवस् Uccaiḥśravas or उच्चैःश्रवा Uccaiḥśravā, "long-ears" or "neighing aloud"[1]) is a seven-headed flying horse, created during the churning of the milk ocean. It is considered the best of horses, archetype and king of horses.[1] Uchchaihshravas is often described as a vahana ("vehicle") of Indra - the god-king of heaven, but is also recorded to be the horse of Bali, the king of demons. Uchchaihshravas is said to be snow white in colour.

Legends and textual references

The Mahabharata mentions that Uchchaihshravas rose from the Samudra manthan ("churning of the milk ocean") and Indra - the god-king of heaven seized it and made it his vehicle (vahana). He rose from the ocean along with other treasures like goddess Lakshmi - the goddess of fortune, taken by god Vishnu as his consort and the amrita - the elixir of life.[2] The legend of Uchchaihshravas, rising from the milk ocean also appears in the Vishnu Purana, the Ramayana, the Matsya Purana, the Vayu Purana etc. While various scriptures give different lists of treasures (ratnas) those appeared from the churning of the milk ocean, most of them agree that Uchchaihshravas was one of them.[3][4]

Uchchaihshravas is also mentioned in the Bhagavad Gita (10.27, which is part of the Mahabharata), a discourse by god Krishna - an avatar of Vishnu - to Arjuna. When Krishna declares to be the source of the universe, he declares that among horses, he is Uchchaihshravas - who is born from the amrita.[5] The 12th century Hariharacaturanga records once Brahma, the creator-god, performed a sacrifice, out of which rose a winged white horse called Uchchaihshravas. Uchchaihshravas again rose out of the milk ocean and was taken by the king of the demons (Asura) Bali, who used it to attain many impossible things.[6] The Vishnu Purana records when Prithu was installed as the first king on earth, others were also given kingship responsibilities. Uchchaihshravas was then made the king of horses.[7]

The Mahabharata also mentions about a bet between sisters and wives of Kashyapa - Vinata and Kadru about the colour of Uchchaihshravas's tail. While Vinata - the mother of Garuda and Aruna said it was white, Kadru said it was black. The loser would have to become a servant of the winner. Kadru told her Naga ("serpent") sons to cover the tail of the horse and thus make it appear as black in colour and thus, Kadru won.[2][3] The Kumarasambhava by Kalidasa, narrates that Uchchaihshravas, the best of horses and symbol of Indra's glory was robbed by the demon Tarakasura from heaven.[8]

Devi Bhagavata Purana narrates that once Revanta, the sun-god Surya's son came to god Vishnu's abode, riding Uchchaihshravas. Seeing Uchchaihshravas - her brother's brilliant form, Lakshmi was mesmerized and ignored a question asked by Vishnu. Suspecting that Lakshmi lusted for Uchchaihshravas and thus ignored him, Vishnu cursed her to be born as a mare in her next birth.[2]

In popular culture

- George Harrison's Dark Horse Records music label uses a logo inspired by Uchchaihshravas.

Notes

- 1 2 Monier Monier-Williams (1819-1899) (2008). "Monier-Williams Sanskrit Dictionary". p. 173. Retrieved 13 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic Encyclopaedia: A Comprehensive Dictionary With Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 800. ISBN 0-8426-0822-2.

- 1 2 Beér, Robert (2004). The encyclopedia of Tibetan symbols and motifs. Serindia Publications, Inc. pp. 65, 109.

- ↑ Horace Hayman Wilson (1840). "The Vishnu Purana: Book I: Chapter IX". Sacred Texts Archive. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ↑ Radhakrishnan, S. (January 1977). "10.27". The Bhagavadgita. Blackie & Son (India) Ltd. p. 264.

- ↑ Dikshitar, V. R. Ramachandra (1999). War in Ancient India. Cosmo Publications. p. 175. ISBN 81-7020-894-7.

- ↑ Horace Hayman Wilson (1840). "Vishnu Purana: Book 1: Chapter XXII". Sacred Texts archive. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ↑ Devahar, C R, ed. (1997). "2.47". Kumāra-Sambhava of Kālidāsa. Motilal Banarasidas Publishers. p. 25.

References

- Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend (ISBN 0-500-51088-1) by Anna Dallapiccola