Two-graph

In mathematics, a two-graph is a set of (unordered) triples chosen from a finite vertex set X, such that every (unordered) quadruple from X contains an even number of triples of the two-graph. A regular two-graph has the property that every pair of vertices lies in the same number of triples of the two-graph. Two-graphs have been studied because of their connection with equiangular lines and, for regular two-graphs, strongly regular graphs, and also finite groups because many regular two-graphs have interesting automorphism groups.

A two-graph is not a graph and should not be confused with other objects called 2-graphs in graph theory, such as 2-regular graphs.

Examples

On the set of vertices {1,...,6} the following collection of unordered triples is a two-graph:

- 123 124 135 146 156 236 245 256 345 346

This two-graph is a regular two-graph since each pair of distinct vertices appears together in exactly two triples.

Given a simple graph G = (V,E), the set of triples of the vertex set V whose induced subgraph has an odd number of edges forms a two-graph on the set V. Every two-graph can be represented in this way.[1] This example is referred to as the standard construction of a two-graph from a simple graph.

As a more complex example, let T be a tree with edge set E. The set of all triples of E that are not contained in a path of T form a two-graph on the set E.[2]

Switching and graphs

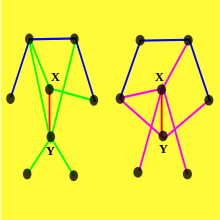

A two-graph is equivalent to a switching class of graphs and also to a (signed) switching class of signed complete graphs.

Switching a set of vertices in a (simple) graph means reversing the adjacencies of each pair of vertices, one in the set and the other not in the set: thus the edge set is changed so that an adjacent pair becomes nonadjacent and a nonadjacent pair becomes adjacent. The edges whose endpoints are both in the set, or both not in the set, are not changed. Graphs are switching equivalent if one can be obtained from the other by switching. An equivalence class of graphs under switching is called a switching class. Switching was introduced by van Lint & Seidel (1966) and developed by Seidel; it has been called graph switching or Seidel switching, partly to distinguish it from switching of signed graphs.

In the standard construction of a two-graph from a simple graph given above, two graphs will yield the same two-graph if and only if they are equivalent under switching, that is, they are in the same switching class.

Let Γ be a two-graph on the set X. For any element x of X, define a graph with vertex set X having vertices y and z adjacent if and only if {x, y, z} is in Γ. In this graph, x will be an isolated vertex. This construction is reversible; given a simple graph G, adjoin a new element x to the set of vertices of G and define the two-graph whose triples are all the {x, y, z} where y and z are adjacent vertices in G. This two-graph is called the extension of G by x in design theoretic language.[3] In a given switching class of graphs of a regular two-graph, let Γx be the unique graph having x as an isolated vertex (this always exists, just take any graph in the class and switch the open neighborhood of x) without the vertex x. That is, the two-graph is the extension of Γx by x. In the first example above of a regular two-graph, Γx is a 5-cycle for any choice of x.[4]

To a graph G there corresponds a signed complete graph Σ on the same vertex set, whose edges are signed negative if in G and positive if not in G. Conversely, G is the subgraph of Σ that consists of all vertices and all negative edges. The two-graph of G can also be defined as the set of triples of vertices that support a negative triangle (a triangle with an odd number of negative edges) in Σ. Two signed complete graphs yield the same two-graph if and only if they are equivalent under switching.

Switching of G and of Σ are related: switching the same vertices in both yields a graph H and its corresponding signed complete graph.

Adjacency matrix

The adjacency matrix of a two-graph is the adjacency matrix of the corresponding signed complete graph; thus it is symmetric, is zero on the diagonal, and has entries ±1 off the diagonal. If G is the graph corresponding to the signed complete graph Σ, this matrix is called the (0, −1, 1)-adjacency matrix or Seidel adjacency matrix of G. The Seidel matrix has zero entries on the main diagonal, -1 entries for adjacent vertices and +1 entries for non-adjacent vertices.

If graphs G and H are in a same switching class, the multisets of eigenvalues of the two Seidel adjacency matrices of G and H coincide, since the matrices are similar.[5]

A two-graph on a set V is regular if and only if its adjacency matrix has just two distinct eigenvalues ρ1 > 0 > ρ2 say, where ρ1ρ2 = 1 - |V|.[6]

Equiangular lines

Every two-graph is equivalent to a set of lines in some dimensional euclidean space each pair of which meet in the same angle. The set of lines constructed from a two graph on n vertices is obtained as follows. Let -ρ be the smallest eigenvalue of the Seidel adjacency matrix, A, of the two-graph, and suppose that it has multiplicity n - d. Then the matrix ρI + A is positive semi-definite of rank d and thus can be represented as the Gram matrix of the inner products of n vectors in euclidean d-space. As these vectors have the same norm (namely, ) and mutual inner products ±1, any pair of the n lines spanned by them meet in the same angle φ where cos φ = 1/ρ. Conversely, any set of non-orthogonal equiangular lines in a euclidean space can give rise to a two-graph (see equiangular lines for the construction).[7]

With the notation as above, the maximum cardinality n satisfies n ≤ d(ρ2 - 1)/(ρ2 - d) and the bound is achieved if and only if the two-graph is regular.

Strongly regular graphs

The two-graphs on X consisting of all possible triples of X and no triples of X are regular two-graphs and are considered to be trivial two-graphs.

For non-trivial two-graphs on the set X, the two-graph is regular if and only if for some x in X the graph Γx is a strongly regular graph with k = 2μ (the degree of any vertex is twice the number of vertices adjacent to both of any non-adjacent pair of vertices). If this condition holds for one x in X, it holds for all the elements of X.[8]

It follows that a non-trivial regular two-graph has an even number of points.

If G is a regular graph whose two-graph extension is Γ having n points, then Γ is a regular two-graph if and only if G is a strongly regular graph with eigenvalues k, r and s satisfying n = 2(k - r) or n = 2(k - s).[9]

Notes

- ↑ Colburn & Dinitz 2007, p. 876, Remark 13.2

- ↑ Cameron, P.J. (1994), "Two-graphs and trees", Discrete Mathematics, 127: 63–74, doi:10.1016/0012-365x(92)00468-7 cited in Colburn & Dinitz 2007, p. 876, Construction 13.12

- ↑ Cameron & van Lint 1991, pp. 58-59

- ↑ Cameron & van Lint 1991, p. 62

- ↑ Cameron & van Lint 1991, p. 61

- ↑ Colburn & Dinitz 2007, p. 878 #13.24

- ↑ van Lint & Seidel 1966

- ↑ Cameron & van Lint 1991, p. 62 Theorem 4.11

- ↑ Cameron & van Lint 1991, p. 62 Theorem 4.12

References

- Brouwer, A.E., Cohen, A.M., and Neumaier, A. (1989), Distance-Regular Graphs. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. Sections 1.5, 3.8, 7.6C.

- Cameron, P.J.; van Lint, J.H. (1991), Designs, Graphs, Codes and their Links, London Mathematical Society Student Texts 22, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-42385-4

- Colbourn, Charles J.; Dinitz, Jeffrey H. (2007), Handbook of Combinatorial Designs (2nd ed.), Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/ CRC, pp. 875–882, ISBN 1-58488-506-8

- Godsil, Chris: Royle, Gordon (2001), Algebraic Graph Theory. Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Vol. 207. Springer-Verlag, New York. Chapter 11.

- Seidel, J. J. (1976), A survey of two-graphs. In: Colloquio Internazionale sulle Teorie Combinatorie (Proceedings, Rome, 1973), Vol. I, pp. 481–511. Atti dei Convegni Lincei, No. 17. Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Rome.

- Taylor, D. E. (1977), Regular 2-graphs. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society (3), vol. 35, pp. 257–274.

- van Lint, J. H.; Seidel, J. J. (1966), "Equilateral point sets in elliptic geometry", Indagationes Mathematicae, Proc. Koninkl. Ned. Akad. Wetenschap. Ser. A 69, 28: 335–348