Tsuchigumo

Tsuchigumo (土蜘蛛), literally translated "dirt/earth spider", is a historical Japanese derogatory term for renegade local clans, and also the name for a race of spider-like yōkai in Japanese folklore. Alternate names for the mythological Tsuchigumo include yatsukahagi (八握脛) and ōgumo (大蜘蛛, "giant spider").[1] In the Kojiki and in Nihon Shoki, they were also referred to by the homophonic synonym 都知久母,[2] and these words were frequently used in the fudoki of Mutsu, Echigo, Hitachi, Settsu, Bungo and Hizen as well as others.

The Japanese name for large ground-dwelling tarantulas, ōtsuchigumo, is due to their perceived resemblance to the creature of the myth, rather than the myth being named for the spider. Japan has no native species of tarantula, and the similarities between the mythical and the actual creature- huge wandering spiders with an obvious face that like to hide in burrows- were entirely coincidental. The fact that the later iterations of the myth specifically refer to the body being that of a tiger, however, does imply that the description was influenced to some degree by the Chinese bird spider, which is commonly referred to as the "earth tiger" in its native habitat for its furry, prominently striped body and aggressive disposition.

Tsuchigumo in history

According to the ancient historian Motoori Norinaga in ancient Japan, Tsuchigumo was used as a derogatory term against aborigines who did not show allegiance to the emperor of Japan.

There is some debate on whether the mythical spider-creature or the historical clans came first. One theory is based on the knowledge that beginning with the earliest historical records, those who waged war against the imperial court were referred to as oni by the imperial court, both in scorn and as a way to demonize enemies of the court by literally referring to them as demons. Tsuchigumo may have been a pre-existing but obscure myth picked as the term of choice for a more humble threat to the empire, after which it was popularized. Alternately, the word tsuchigumo has been identified a derivation of an older derogatory term, tsuchigomori (土隠),[3] which roughly translates as "those who hide in the ground". This term refers to a common practice among many of the rural clans: utilizing existing cave systems and creating fortified hollow earthen mounds for both residential and military purposes.This implies that the use of the name for renegade clans began essentially as a pun, and over time tales surrounding a literal race of intelligent, occasionally anthropomorphic, spiders grew from this historical usage, first as allegory, then as myth.

In the following examples from ancient historical records and accounts, tsuchigumo is used variously to describe well-known individual bandits, rebels, or unruly clan leaders, and also applied to clans as a whole. In some cases it is unclear in which way the term is being used. Its usage as a figurative term denotes that the person or clan referred to was defying Imperial authority in some covert but consistent fashion, generally by guerrilla warfare or actively eluding discovery.

Tsuchigumo of the Katsuragi

Of the clans referred to as tsuchigumo, those of the Mount Yamato Katsuragi are particularly well known. Katsuragi Hitokotonushi Shrine (葛城一言主神社 Katsuragi Hitokotonushi Jinja) was said to be the remains where Emperor Jimmu captured tsuchigumo and buried their head, body and feet separately to prevent their grudges from harming the living.[4]

In historic Yamato Province, the unique physical characteristics of the tsuchigumo were that they were tailed people. In the Nihon Shoki, the founder of the Yoshino no Futo (吉野首) were written to be "with a glowing tail," the founder of Yoshino no Kuzu (国樔) were stated to "have tails and come along pushing rocks (磐石, iwa)," presenting the indigenous people of Yamato as non-humans. Even in the Kojiki, they shared a common trait with the people of Osaka (忍坂) (now Sakurai city) in that they were "tsuchigumo (土雲) who have grown tails."

Records from the Keiko generation and others

In the Hizen no Kuni Fudoki, there is an article writing that when Emperor Keiko made an imperial visit to Shiki island (志式島, Hirado island) (year 72 in the legends), the expedition encountered a pair of islands in the middle of sea. Seeing smoke rising from inland, the Emperor ordered an investigation of the islands, and discovered that the tsuchigumo Oomimi (大耳) lived on the smaller island, and Taremimi (垂耳) lived on the larger island. When both were captured and about to be killed, Oomimi and Taremimi lowered their foreheads to the ground and fell prostrate, and pleaded, "we will from now on make offerings to the emperor" and presented fish products and begged for pardon.

Also, in the Bungo no Kuni Fudoki, there appeared many tsuchigumo, such as the Itsuma-hime (五馬姫) of Itsuma mountain (五馬山), the Uchisaru (打猴), Unasaru (頸猴), Yata (八田), Kunimaro (國摩侶), and Amashino (網磯野), of Negi field (禰宜野), the Shinokaomi (小竹鹿臣) of Shinokaosa (小竹鹿奥), and the Ao (青) and Shiro (白) of Nezumi cavern (鼠の磐窟). Other than these, there is also the story of Tsuchigumo Yasome (土蜘蛛八十女), who made preparations in the mountains to resist against the imperial court, but was utterly defeated. This word "Yaso" (八十), literally "eighty," is a figurative term for "many," so this story is interpreted to mean that many of the female chief class opposed the Yamato imperial court, and met a heroic end, choosing to die alongside their men. In the story, Yaso, one local female chief, was greatly popular among the people, and she separated her allies from those resisting the imperial forces. Tsuchigumo Yasome's whereabouts were reported to the emperor, and for her efforts she was spared.[5]

According to writings in the Nihon Shoki, in the 12th year of emperor Keiko (year 82 in the legends), in winter, October, emperor Keiko arrived in Hayami town, Ookita (now Ooita), and heard from the queen of the land, Hayatsuhime (速津媛) that there was a big cave in the mountain, called the Nezumi cave, where two tsuchigumo, Shiro and Ao, lived. In Negino (禰疑野), Naoiri, they were informed of three more tsuchigumo named Uchizaru (打猿), Yata (八田), and Kunimaro (国摩侶, 国麻呂). These five had great amount of allies, and would not follow the emperor's commands.[6]

Yōkai tsuchigumo

With the passage of time, Tsuchigumo have also been established as yōkai.[7]

They appeared to people as having faces of an oni, a body of a tiger, arms and legs of a spider, and wore giant outfits. They all lived in mountains, firmly captured travelers with strings, and ate them.

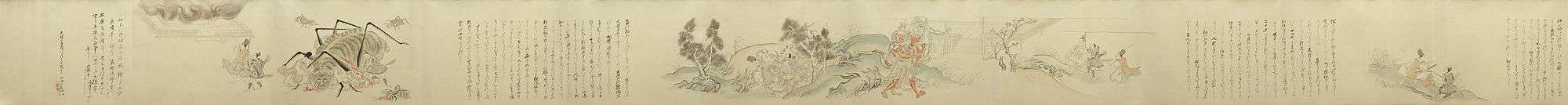

In the Tsuchigumo Soushi (土蜘蛛草紙) written in the 14th century, tsuchigumo appeared in the capital as monsters. The commander Minamoto no Yorimitsu of the mid Heian era, known for the slaying of Shuten-doji, was brought by his servant Watanabe no Tsuna to go in the direction of Rendai field (蓮台野), a mountain north of Kyoto, where they encountered a flying skull. Yorimitsu and the others, who thought it was dubious, started to follow it, and arrived at an old estate, where there appeared various atypical yokai that agonized Yorimitsu and the others, and when dawn arrived, there appeared a beautiful woman who was about to trick them, but Yorimitsu, not giving in, cut it with his katana, and the woman disappeared, leaving white blood. Pursuing that trail, they arrived at a cave in mountain recesses, where there was a huge spider, who was the true identity of all the monsters that appeared. At the end of a long battle, Yorimitsu cut off the spider's head, and the heads of 1,990 dead people came out from its stomach. Furthermore, from its flanks, countless small spiders flew about, and investigating them further, they found about 20 more skulls.[8][9]

There are various theories to the story of the tsuchigumo, and in the Heike Monogatari, there is as following (they were written as 山蜘蛛). When Yorimitsu suffered from malaria, and lay on a bed, a strange monk who was 7 shaku (about 2.1 meters) tall appeared, released some rope, and tried to capture him. Yorimitsu, despite his sickness, cut him with his famous sword, the Hizamaru (膝丸), causing the monk to flee. The next day, Yorimitsu led his Four Guardian Kings to chase after the blood trail of the monk, and arrived at a mound behind Kitano jinja where there was a large spider that was 4 shaku wide (about 1.2 meters). Yorimitsu and the others caught it, pierced it with an iron skewer, and exposed it to a riverbed. Yorimitsu's illness left him immediately, and the sword that cut the spider was from then on called the Kumo-kiri (蜘蛛切り, spider-cutter).[10] The true identity of this tsuchigumo was said to be an onryō of the aforementioned local clan defeated by Emperor Jimmu.[2] This tale is also known from the very fifth noh, "Tsuchigumo."[2]

In one story, Yorimitsu's father, Minamoto no Mitsunaka, conspired with the aforementioned oni and tsuchigumo local clan and planned a revolt against the Fujiwara clan, but during the "Anna no Hen" when he betrayed the local clan to protect himself, it has been said that his son, Yorimitsu, and his guardian kings will be cursed by oni and tsuchigumo yokai.[11]

In Kita-ku, Kyoto, Jōbonrendai-ji, there is the Minamoto Yorimitsu Ason-no-tsuka (源頼光朝臣塚) deifying Yorimitsu, but this mound has been said to be a nest built by tsuchigumo, and there is a story that when the tree that was previously beside it fell to lumbering, the logger fell into a mysterious illness and died.[10] Also, in Ichijō-dōri in Kamigyō-ku, there is also a mound said to be built from tsuchigumo, where lanterns were discovered in an excavation and said to be spider lanterns, but those who received this immediately started to trend to receive great fortune, and became afraid of being cursed by tsuchigumo, so these spider lanterns are now dedicated to the temple Tōkō-Kannon-ji in Kannonji-monzen-chō, Kamigyō-ku.[10]

There is also a similar yokai called umigumo (海蜘蛛). They are said to send out strings from their mouths and attack people. Their appearance has been set to be the coast of Kyushu.[12]

See also

![]() Media related to Tsuchigumo at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tsuchigumo at Wikimedia Commons

References

- ↑ 岩井宏實 (2000). 暮しの中の妖怪たち. 河出文庫. 河出書房新社. pp. 156頁. ISBN 978-4-309-47396-3.

- 1 2 3 京極夏彦・多田克己 編著 (2008). 妖怪画本 狂歌百物語. 国書刊行会. pp. 293–294頁. ISBN 978-4-3360-5055-7.

- ↑ 奈良国立文化財研究所 佐原眞 『体系 日本の歴史 1 日本人の誕生』 小学館、1987年、178頁。ISBN 4-09-622001-9。

- ↑ 村上健司 編著 (2000). 妖怪事典. 毎日新聞社. pp. 222頁. ISBN 978-4-620-31428-0.

- ↑ 義江明子『古代女性史への招待――“妹の力”を超えて』

- ↑ 日本書紀 の参考部分:日本書紀 巻第七日本書紀(朝日新聞社本)《景行天皇十二年(壬午八二)十月》冬十月。到碩田国。・・・因名碩田也。・・・到速見邑。有女人。曰速津媛。・・・茲山有大石窟。曰鼠石窟。有二土蜘蛛。住其石窟。一曰青。二曰白。又於直入県禰疑野、有三土蜘蛛。一曰打猿。二曰八田。三曰国摩侶。是五人並其為人強力。亦衆類多之。皆曰。不従皇命。

- ↑ "土蜘蛛 | ツチグモ | 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース". Nichibun.ac.jp. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- ↑ 谷川健一 監修 (1987). 別冊太陽 日本の妖怪. 平凡社. pp. 64–74頁. ISBN 978-4-582-92057-4.

- ↑ 宮本幸江・熊谷あづさ (2007). 日本の妖怪の謎と不思議. 学研ホールディングス. pp. 74頁. ISBN 978-4-056-04760-8.

- 1 2 3 村上健司 (2008). 日本妖怪散歩. 角川文庫. 角川書店. pp. 210–211頁. ISBN 978-4-04-391001-4.

- ↑ 多田克己 (1990). 幻想世界の住人たち IV 日本編. Truth in fantasy. 新紀元社. pp. 77頁. ISBN 978-4-915146-44-2.

- ↑ 山口敏太郎・天野ミチヒロ (2007). 決定版! 本当にいる日本・世界の「未知生物」案内. 笠倉出版社. pp. 32頁. ISBN 978-4-7730-0364-2.

Further reading

- Asiatic Society of Japan. Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan: Volume 7. The Society. (1879)

- Aston, William George. Shinto: the way of the gods. Longmans, Green, and Co. (1905)

- Brinkley, Frank and Dairoku Kikuchi. A history of the Japanese people from the earliest times to the end of the Meiji era. The Encyclopædia Britannica Co. (1915)

- Horne, Charles Francis. The Sacred books and early literature of the East. Parke, Austin, and Lipscomb: (1917)

- Studio international, Volume 18. Studio Trust. (1900)

- Trench, K. Paul. Nihongi: chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697: Volume 1. The Society. Trübner. (1896)