Strombidae

| Strombidae | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Three shells of three species in the family Strombidae: lower left Laevistrombus turturella, upper center Lambis lambis, lower right Euprotomus aurisdianae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Clade: | Caenogastropoda |

| Clade: | Hypsogastropoda |

| Clade: | Littorinimorpha |

| Superfamily: | Stromboidea |

| Family: | Strombidae Rafinesque, 1815 |

| Genera | |

|

See text | |

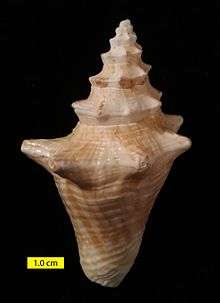

Strombidae, commonly known as the true conchs, is a taxonomic family of medium-sized to very large sea snails in the superfamily Stromboidea.

The family Strombidae includes the genera Strombus, Lambis, Tibia, and their allies. In the geological past, many more species existed than are now extant.

The term true conchs, being a common name, does not have an exact meaning. It may refer generally to any of the Strombidae[1] but sometimes is used more specifically to include only Strombus and Lambis[2] or just Strombus itself.[3]

Distribution

Strombid gastropods live mainly in tropical and subtropical waters. These animals are widespread in the Indo-West Pacific, where most species and genera occur.[4] Nearly forty of the living species that used to belong to the genus Strombus can be found in the Indo-Pacific region.[5] They also occur in the eastern Pacific and Western Atlantic, and a single species can be found on the African Atlantic coast.[4] Six species of strombids are found in the wider Caribbean region, including the queen conch Lobatus gigas, the goliath conch Lobatus goliath, the hawk-wing conch Lobatus raninus, the rooster tail conch Lobatus gallus, the milk conch Lobatus costatus, the West Indian fighting conch Strombus pugilis and the Florida fighting conch Strombus alatus. Until recently, all of these species were placed in the genus Strombus, but now many species are being moved into new genera.[6]

Morphology and life habits

Strombids have long eye stalks. The shell of a strombid has a long and narrow aperture and a siphonal canal. The shell margin has an indentation near the anterior end which accommodates one of the eye stalks. This indentation is called a strombid or stromboid notch. The stromboid notch may be more or less conspicuous, depending on the species.[7] The shell of most species in this family grow a flared lip upon reaching sexual maturity, and they lay eggs in long, gelatinous strands. The genera Strombus and Lambis have many similarities between them, both anatomical and reproductive, though their shells show some conspicuous differences.

Strombid were widely accepted as carnivores by several authors in the 19th century, an erroneous concept that persisted for several decades into the first half of the 20th century. This ideology was probably born in the writings of Lamarck, who classified strombids alongside other supposedly carnivorous snails, and was copied in this by subsequent authors. However, the many claims of those authors were never supported by the observation of animals feeding in their natural habitat.[8] Nowadays, strombids are known to be specialized herbivores and occasional detritivores. They are usually associated with shallow water reefs and seagrass meadows.[9]

Behavior

Unlike most snails, which glide slowly across the substrate on their foot, strombid gastropods have a characteristic means of locomotion, using their pointed, sickle-shaped, horny operculum to propel themselves forward in a so-called leaping motion.[1][10]

Burrowing behaviour, in which an individual sinks itself entirely or partially into the substrate, is also frequent among strombid gastropods. The burrowing process itself, which involves distinct sequential movements and sometimes complex behaviours, is very characteristic of each species. Usually, large strombid gastropods such as the queen conch Eustrombus gigas and the spider conch Lambis lambis, do not bury themselves, except during their juvenile stage. On the other hand, smaller species such as the dog conch Strombus canarium and Strombus epidromis may bury themselves even after adulthood, though this is not an absolute rule.[11]

Taxonomy

For a long time all conchs and their allies (the strombids) were classified in only two genera, namely Strombus and Lambis. This classification can still be found in many textbooks and on websites on the internet. Based on molecular phylogeny[9] as well as a well-known fossil record, both genera have been subdivided into several new genera by different authors.[6][12][13]

Genera

The family Strombidae actually comprises several genera (extinct genera are marked with a dagger †), including:[12]

- Barneystrombus Blackwood, 2009

- Canarium Schumacher, 1817

- Conomurex Bayle in P. Fischer, 1884

- Dolomena Wenz, 1940

- Doxander Wenz, 1940

- Euprotomus Gill, 1870

- †Europrotomus Kronenberg & Harzhauser, 2011

- Gibberulus Jousseaume, 1888

- Harpago Mörch, 1852

- Labiostrombus Oostingh, 1925

- Laevistrombus Abbott, 1960

- Lambis Röding, 1798

- Lentigo Jousseaume, 1886

- Lobatus Swainson, 1837

- Margistrombus Bandel, 2007

- Mirabilistrombus Kronenberg, 1998

- Ophioglossolambis Dekkers, 2012

- Persististrombus Kronenberg & Lee, 2007

- Sinustrombus Bandel, 2007

- Strombus Linnaeus, 1758

- Terestrombus Kronenberg & Vermeij, 2002

- Thersistrombus Bandel, 2007

- Tricornis Jousseaume, 1886

- Tridentarius Kronenberg & Vermeij, 2002

- Genera brought into synonymy

- Afristrombus Bandel, 2007 : synonym of Persististrombus Kronenberg & Lee, 2007

- Aliger Thiele, 1929 : synonym of Lobatus Swainson, 1837

- Decostrombus Bandel, 2007 : synonym of Conomurex Bayle in P. Fischer, 1884

- Eustrombus Wenz, 1940 : synonym of Lobatus Swainson, 1837

- Fusistrombus Bandel, 2007 : synonym of Canarium Schumacher, 1817

- Gallinula Mörch, 1852 : synonym of Labiostrombus Oostingh, 1925

- Hawaiistrombus Bandel, 2007 : synonym of Canarium Schumacher, 1817

- Heptadactylus Mörch, 1852 : synonym of Lambis Röding, 1798

- Latissistrombus Bandel, 2007 : synonym of Sinustrombus Bandel, 2007

- Macrostrombus Petuch, 1994 : synonym of Lobatus Swainson, 1837

- Millipes Mörch, 1852 : synonym of Lambis Röding, 1798

- Ministrombus Bandel, 2007 : synonym of Dolomena Wenz, 1940

- Monodactylus Mörch, 1852 : synonym of Euprotomus Gill, 1870

- Neodilatilabrum Dekkers, 2008 : synonym of Margistrombus Bandel, 2007

- Pterocera Lamarck, 1799 : synonym of Lambis Röding, 1798

- Pyramis Röding, 1798 : synonym of Strombus Linnaeus, 1758

- Solidistrombus Dekkers, 2008 : synonym of Sinustrombus Bandel, 2007

- Strombella Schlüter, 1838 : synonym of Strombus Linnaeus, 1758

- Strombidea Swainson, 1840 : synonym of Canarium Schumacher, 1817

- Thetystrombus Dekkers, 2008 : synonym of Persististrombus Kronenberg & Lee, 2007

- Titanostrombus Petuch, 1994 : synonym of Lobatus Swainson, 1837

- Five views of a shell of Conomurex luhuanus, type species of the genus Conomurex

- Five views of a shell of Canarium urceus, a species of the genus Canarium

- Five views of a shell of Dolomena variabilis, a species in the genus Dolomena

- Five views of a shell of Doxander vittatus, a species in the genus Doxander

- Five views of a shell of Euprotomus aurisdianae, type species of the genus Euprotomus

- Five views of a shell of Laevistrombus canarium, type species of the genus Laevistrombus

Lobatus gigas, a species in the genus Lobatus

Lobatus gigas, a species in the genus Lobatus- Five views of a shell of Lambis lambis, a species in the genus Lambis

Strombus alatus, a species in the genus Strombus

Strombus alatus, a species in the genus Strombus

Phylogeny

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny and relationships of Strombidae according to Simone (2005)[7] |

The phylogenetic relationships among the Strombidae have been mainly accessed in two different occasions, using two distinct methods. In a 2005 monograph, Simone proposed a cladogram (a tree of descent) based on an extensive morpho-anatomical analysis of representatives of Aporrhaidae, Strombidae, Xenophoridae and Struthiolariidae.[7] In his analysis, Simone recognized Strombidae as a monophyletic taxon supported by 13 synapomorphies (traits that are shared by two or more taxa and their most recent common ancestor), comprising at least eight distinct genera. He considered the genus Terebellum as the most basal taxon, distinguished from the remaining strombids by 13 synapomorphies, including a rounded foot.[7] Though the genus Tibia was left out of the analysis, Simone regarded it as probably closely related to Terebellum, apparently due to some well known morphological similarities between them.[7] With the exception of Lambis, the remaining taxa were previously allocated within the genus Strombus. However, according to Simone, only Strombus gracilior, Strombus alatus and Strombus pugilis, the type species, remained within Strombus, as they constituted a distinct group based on at least five synapomorphies.[7] The remaining taxa were previously considered as subgenera, and were elevated to genus level by Simone in the end of his analysis. The genus Eustrombus (now considered a synonym of Lobatus),[12] in this case, included Eustrombus gigas (now considered a synonym of Lobatus gigas) and Eustrombus goliath (= Lobatus goliath); similarly, the genus Aliger included Aliger costatus (= Lobatus costatus) and Aliger gallus (= Lobatus gallus).[7][12]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogeny and relationships of Strombidae according to Latiolais (2006)[9] |

A different approach, this time based on sequences of nuclear histone H3 and mitochondrial cytochrome-c oxidase I (COI) genes was proposed by Latiolais and colleagues in a 2006 paper. The analysis included 32 strombid species that used to, or still belong in the genus Strombus and Lambis.[9]

Human use

Several species belonging to numerous genera among Strombidae are considered economically important.[14] Used as food, fishing bait, tools or simply as decoration, some strombid snail species have been used in human culture for centuries.[15][16]

References

- 1 2 Abbott, R. T.; Dance, S. P. (2000). Compendium of Seashells. California: Odyssey Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 0-9661720-0-0.

- ↑ Goodenough, W. H. & Sugita, H. (1980). "Trukese-English dictionary". Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. p. 235]

- ↑ worldwideconchiology.com Strombidae article

- 1 2 Beesley, P. L.; Ross, G. J. B.; Wells, A. (1998). Mollusca: The Southern Synthesis. Fauna of Australia: Part B. Melbourne, AU: CSIRO Publishing. p. 766. ISBN 0-643-05756-0.

- ↑ Abbott, R.T. (1960). "The genus Strombus in the Indo-Pacific". Indo-Pacific Mollusca 1(2): 33-144

- 1 2 Landau, B. M.; Kronenberg G. C.; Herbert, G. S. (2008). "A large new species of Lobatus (Gastropoda: Strombidae) from the Neogene of the Dominican Republic, with notes on the genus". The Veliger. Santa Barbara: California Malacozoological Society, Inc. 50 (1): 31–38. ISSN 0042-3211.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Simone, L. R. L. (2005). "Comparative morphological study of representatives of the three families of Stromboidea and the Xenophoroidea (Mollusca, Caenogastropoda), with an assessment of their phylogeny". Arquivos de Zoologia. São Paulo, Brazil: Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo. 37 (2): 141–267. ISSN 0066-7870.

- ↑ Robertson, R. (1961). "The feeding of Strombus and related herbivorous marine gastropods". Notulae Naturae of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (343): 1–9.

- 1 2 3 4 Latiolais J. M., Taylor M. S., Roy K. & Hellberg M. E. (2006). "A molecular phylogenetic analysis of strombid gastropod morphological diversity". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 41: 436-444. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.027. PDF.

- ↑ Parker, G. H. (1922). "The leaping of the stromb (Strombus gigas Linn.)". Journal of Experimental Zoology 36: 205-209.

- ↑ Savazzi, E. (1989). "New observations on burrowing in strombid gastropods". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde. Serie A (Biologie). Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde (434): 1–10. ISSN 0341-0145.

- 1 2 3 4 Strombidae Rafinesque, 1815. Retrieved through: World Register of Marine Species on 22 March 2011.

- ↑ Dekkers, A.M. (2012). "A new genus related to the genus Lambis Röding, 1798 (Gastropoda: Strombidae) from the Indian Ocean". Gloria Maris. 51 (2-3): 68–74.

- ↑ Poutiers, J. M. (1998). "Gastropods". In Carpenter, K. E. The living marine resources of the Western Central Pacific (PDF). Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). p. 471. ISBN 92-5-104051-6.

- ↑ Arularasan, S.; et al. (2010). "Recipes for the Mesogastropod - Strombus canarium" (PDF). Advance Journal of Food Science and Technology. Maxwell Scientific Organization. 2 (1): 31–35. ISSN 2042-4876.

- ↑ Squires, K. (1941). "Pre-Columbian Man in Southern Florida" (PDF). Tequesta. Florida International University (1): 39–46.

Further reading

- Roy K. (1996). "The roles of mass extinction and biotic interaction in large-scale replacements: a reexamination using the fossil record of stromboidean gastropods". Paleobiology 22(3): 436-452. pdf JSTOR

- Roy K., Balch D. P. & Hellberg M. E. (2001). "Spatial patterns of morphological diversity across the Indo-Pacific: analyses using strombid gastropods". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 268: 2503-2508. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1428. PDF

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Strombidae. |

- "Strombidae". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

- Gastropoda Stromboidea - Ulrich Wieneke and Han Stoutjesdijk

- Worldwide Conchology Strombidae

- Strombidae Lambis Eye - photos

- the difference between a conch and a whelk