Smooth newt

| Smooth newt | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Caudata |

| Family: | Salamandridae |

| Genus: | Lissotriton |

| Species: | L. vulgaris |

| Binomial name | |

| Lissotriton vulgaris (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

L. vulgaris ampelensis | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Triturus vulgaris | |

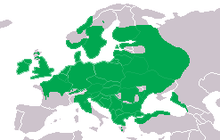

The smooth newt, also known as the common newt (Lissotriton vulgaris; formerly Triturus vulgaris) is a species of amphibian, the most common newt of the genus Lissotriton. It is found throughout Europe, except the far north, areas of Southern France and the Iberian Peninsula.[2]

Description

Outside the breeding season, male and female smooth newts are hard to distinguish – both sexes are of similar size (roughly 10 cm head-to-tail length), and a similar pale brown to yellow colouration. Their main visible differences are two – the male newt has a single black line running down the centre of the spine, the female has two parallel lines on either side of the centre. On closer inspection, the male's cloaca is very distended, whilst the female's is nearly invisible.

During the breeding season, the male becomes darker than the female, and develops a tall, wavy, translucent crest along the spine and tail, with dark spots covering the rest of the body, including the belly, which becomes a far more vivid pink or orange colour than it is in winter and autumn. The female also develops spots, but not on the belly, which is paler than those of the males, and they are generally smaller. The female does not develop a crest. Smooth newts have paddle-like tails for increased swimming speeds.

The nominal subspecies, L. v. vulgaris, is found in the United Kingdom and Ireland.

Females and nonbreeding males are pale brown or olive green, often with two darker stripes on the back. Both sexes have orange bellies, although paler in females, which is covered in rounded black spots. They also have pale throats with conspicuous spots. This helps to distinguish them from palmate newts that have pale unspotted throats, and with which they are often confused. When on land, they have velvety skin. During the breeding season, male smooth newts develop a continuous wavy (rather than jagged) crest that runs from their heads to their tails, and their spotted markings become more apparent. They are also distinguishable from females by their fringed toes.

Distribution and habitat

The smooth newt occurs in western Asia and most of Europe. It is not present in southern France, in southern Italy and the Iberian Peninsula, and is also not found on many Mediterranean islands. It is typically a lowland species, ranging up to about 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) but reaches 2,150 metres (7,050 ft) in Austria. It is found in damp meadows, field edges, parks, gardens, woods and stone piles.[3]

Life cycle

Adult smooth newts emerge from hibernation on land from late February to May, and head towards fresh water to breed. They favour ponds and shallow lakesides over running water. At this time, both sexes become more strikingly and colourfully marked, with vivid spots and orange bellies. The male also develops a wavy crest along the back and tail – the sexes are clearly different during the breeding season.

During courtship, the male newt displays for his prospective mate by vibrating his tail in front of her in a distinctive fashion. The male then deposits a sperm-containing capsule, a spermatophore, in front of his mate, who manoeuvres herself into a position where she can pick up the capsule with her cloaca – fertilisation then occurring inside the female. Thus fertilised, after a few days the female starts to lay eggs. These are placed individually, usually under aquatic plant leaves at a rate of seven to 12 eggs per day. Altogether, a total of 400 eggs may be produced over the season.

After two to three weeks (depending on water temperature), the eggs hatch to a larval form – a tadpole or eft. For a few days, the larvae live off the food reserves contained within their yolk sacs (left over from the egg stage). After this, they start to eat freshwater plankton, and later insect larvae, molluscs, and similar foods (unlike frog and toad tadpoles, newts are carnivorous throughout their lives).

- A well-advanced larval newt, with feathery gills

_nymph.jpg) Nymph

Nymph

The newt larvae initially look like small fish fry, but later they become similar to miniature adults, but with "feathery" external gills emerging from behind the head on either side. As the tadpoles mature, they develop legs (front first), and the growth and use of their lungs is matched by a gradual shrinkage of the gills. Thus, the larva gradually shifts from being fully aquatic to possessing a body suitable for a mostly terrestrial existence, the young newt typically leaving the water after 10 weeks. However, some may overwinter in the larval state, only emerging from the water the following year.[4] Smooth newts take around three years to become sexually mature, on average living for six years. Most adult and juvenile newts hibernate over winter in moist, sheltered areas above ground, emerging in the spring.

Mate selection

Female mate choice is an important concept in evolutionary biology because it bears on female and male reproductive success. Experiments were carried out with Lissotriton vulgarus in which female newts were paired sequentially with two males having different degrees of genetic relatedness to the female. It was found that the more genetically dissimilar male had a higher paternity share than the less related male.[5] Female choice may reflect an avoidance of inbreeding with related males that could lead to less fit progeny (inbreeding depression).

Conservation status

All species of newts are protected in Europe. Laws prohibit the killing, destruction, and the selling of newts. While the species is by no means endangered, IUCN lists insufficient data to make an assessment for two of the subspecies.

In the UK, the smooth newt is protected under Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981) with respect to sale only. It is therefore illegal to sell individuals of the species, but their destruction or capture is still permitted. They are also listed under Annex III of the Bern Convention. The smooth newt is the only newt native to Ireland, and it is protected there under the Wildlife Acts (1976 and 2000). It is an offence to capture or kill a newt in Ireland without a licence.[6]

Name

Until around 2000, the smooth newt was classified as Triturus vulgaris rather than Lissotriton vulgaris, and will be found under that name in most books and many websites. The old genus Triturus was found to be a wastebasket taxon, and the smooth newt was transferred to Lissotriton together with the other small-bodied newts.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lissotriton vulgaris. |

- ↑ Jan Willem Arntzen, Sergius Kuzmin, Trevor Beebee, Theodore Papenfuss, Max Sparreboom, Ismail H. Ugurtas, Steven Anderson, Brandon Anthony, Franco Andreone, David Tarkhnishvili, Vladimir Ishchenko, Natalia Ananjeva, Nikolai Orlov, Boris Tuniyev (2009) Lissotriton vulgaris. In: IUCN 2012. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2.

- ↑ Nature: Smooth Newt. BBC (2012-04-27). Retrieved on 2013-01-03.

- ↑ Arnold, E. Nicholas; Ovenden, Denys W. (2002). Field Guide: Reptiles & Amphibians of Britain & Europe. Collins & Co. pp. 46–47. ISBN 9780002199643.

- ↑ British Smooth Newts. Mjking.org (2008-05-26). Retrieved on 2013-01-03.

- ↑ Jehle R, Sztatecsny M, Wolf JB, Whitlock A, Hödl W, Burke T (2007). "Genetic dissimilarity predicts paternity in the smooth newt (Lissotriton vulgaris)". Biol. Lett. 3 (5): 526–8. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0311. PMC 2391198

. PMID 17638673.

. PMID 17638673. - ↑ National Parks & Wildlife Service. Npws.ie. Retrieved on 2013-01-03.

Further reading

"The Life Cycle of the Newt". British Film Council. 1942. Retrieved 24 April 2014.