Timeline of egg fossil research

This timeline of egg fossils research is a chronologically ordered list of important discoveries, controversies of interpretation, taxonomic revisions, and cultural portrayals of egg fossils. Humans have encountered egg fossils for thousands of years. In stone age Mongolia, local peoples fashioned fossil dinosaur eggshell into jewelry. In the Americas, fossil eggs may have inspired Navajo creation myths about the human theft of a primordial water monster's egg. Nevertheless, the scientific study of fossil eggs began much later. As reptiles, dinosaurs were presumed to have laid eggs from the 1820s on, when their first scientifically documented remains were being described in England.[1] In 1859, the first scientifically documented dinosaur egg fossils were discovered in southern France by a Catholic priest and amateur naturalist named Father Jean-Jacques Poech, however he thought they were laid by giant birds.

The first scientifically recognized dinosaur egg fossils were discovered serendipitously in 1923 by an American Museum of Natural History crew while looking for evidence of early humans in Mongolia. These eggs were mistakenly attributed to the locally abundant herbivore Protoceratops, but are now known to be Oviraptor eggs. Egg discoveries continued to mount all over the world, leading to the development of multiple competing classification schemes. In 1975 Chinese paleontologist Zhao Zi-Kui started a revolution in fossil egg classification by developing a system of "parataxonomy" based on the traditional Linnaean system to classify eggs based on their physical qualities rather than their hypothesized mothers. Zhao's new method of egg classification was hindered from adoption by Western scientists due to language barriers. However, in the early 1990s Russian paleontologist Konstantin Mikhailov brought attention to Zhao's work in the English language scientific literature.

Prescientific

Late Paleolithic to early Neolithic

- Mongolians fashioned fossil dinosaur eggshell into jewelry.[2]

Precolumbian North America

- A common theme in Navajo stories about Water Monsters involve the human theft of Water Monster eggs or young and the angry Monsters pursuing humanity through a series of worlds.[3] Stories like this influenced the Navajos to fear large fossil bones, which they felt shouldn't be disturbed, because doing so might awaken the enraged ghosts of the Water Monsters, who might resume their rampage with apocalyptic results.[4] Stories like this may have been based on the discovery of fossil eggs in western North America. Fossil eggs and nests from this region that may have inspired the legend were left behind by creatures like possible aetosaurs, giant condors, duck-billed dinosaurs, possible phytosaurs, large theropods, and sea turtles.[5]

19th-century paleontology

- The first scientifically documented dinosaur egg fossils were discovered in southern France by a Catholic priest and amateur naturalist named Father Jean-Jacques Pouech.[6] These fossils were large chunks of eggshell that date back to the Late Cretaceous.[2] Poech mistook them for the shell of a giant bird's eggs.[6]

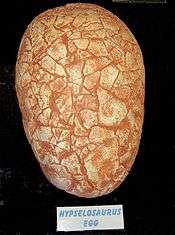

- French geologist Phillippe Matheron made a fossil discovery in the same general region as Poech. Matheron discovered the fossil bones of an animal he named Hypselosaurus. Matheron thought Hypselosaurus to be a crocodile-like animal,[7] but it is now recognized as a long-necked herbivorous sauropod dinosaur.[8] Eggshell fossils were found associated with the remains. Matheron presented the shell fossils to the director of comparative anatomy at Paris' Natural History Museum, Paul Gervais.[7] Gervais examined thin sections of the shell fossils and compared them with similar thin sections of eggs laid by modern birds and reptiles. He found them to be most similar to turtle eggs, but recognized that since dinosaur eggs had not yet been described scientifically, he could not rule out that possibility.[9]

20th-century paleontology

- While prospecting on the Blackfoot Reservation of northern Montana on behalf of the National Museum of Natural History, Charles W. Gilmore found a deposit of apparent freshwater clam fossils.[10] He collected samples, noted the location and photographed the site.[11] These "clamshell" fossils were actually the first dinosaur eggshell collected by scientists in the United States.[10]

- Roy Chapman Andrews proposed the idea of a scientific expedition into central Asia to test Henry Fairfield Osborn's hypothesis that humanity originated in Asia.[12]

- April 17th: The Central Asiatic Expedition, led by Andrews, departed from Peking toward Mongolia.[13]

- July 13th: Over dinner, Central Asiatic Expedition member George Olsen claimed to have found fossil eggs. The other expedition members were skeptical, but Olsen took them to the site of his find. Expedition paleontologist W. Granger recognized them as dinosaur eggs, but mistakenly believed them to be the first ever discovered.[2]

- Alfred Sherwood Romer and Lewellyn Price described a 5.9 cm by 3.79 cm fossil egg from the Lower Permian as the oldest hard-shelled fossil egg.[14] The composition of its shell would later be disputed, but if the fossil was correctly identified as a reptile egg it is the oldest known.[14]

- Summer Soviet scientists embarked on an expedition to Mongolia retracing part of the journey taken by the Central Asiatic Expedition. They discovered many additional dinosaur eggs, some from previously undiscovered fossil sites.[15]

- The first scientifically documented dinosaur eggs from India were discovered by M. Sahni.[16]

- The first scientifically documented dinosaur eggshell from Canada was discovered on the banks of the Milk River in southern Alberta.[17]

- Paleontologist U. Lehman made the first plausible report of ammonite egg fossils in the scientific literature. The apparent clutch of eggs was preserved in the sediment that filled in the living chamber of a harboceratid dating back to the Toarcian age of the Jurassic period. The fossil itself was discovered in a concretion incorporated into glacial drift that came from the Baltic region. The shell containing the putative eggs was a fully grown individual with a macroconch shell.[18]

- Paleontologist A. H. Müller made the second plausible scientific report of fossil ammonite eggs. These eggs were associated with another adult macroconch, that of Ceratites from the Muschelkalk of Germany. The fossil dated to the Upper Anisian age of the Triassic period.[18]

- Jim Jensen reported the discovery of dinosaur eggshell in the Early Cretaceous Cedar Mountain Formation of eastern Utah.[19]

- German paleontologist H. Erben was the first to use scanning electron miscroscopy to study dinosaur eggshell. The level of detail was so much higher than that seen through light microscopy that Erben referred to what he saw as the egg's "ultrastructure".[20]

Folinsbee and his colleagues became one of the first research teams to study dinosaur eggs using mass spectrometry. They found that the eggshell of fossil eggs they attributed to the dinosaur Protoceratops (actually Oviraptor) had more delta Oxygen 18 compared to delta Oxygen 16 in the calcium carbonate of their shell. This implies that the mother's drinking water had a higher percentage of the heavier oxygen in its water molecules due to evaporation, which meant the environment was hot.[21]

They also found that the carbon in the eggshell is mostly the heavier Carbon 13 rather than the lighterCarbon 12. This means the dinosaur were primarily feeding on C3 plants which use 3 carbon atoms in their photosynthesis products rather than C4 plants that use four.[22]

- Chinese paleontologist Zhao Zhi-Kui began developing the "parataxonomy" that serves as the basis for the scientific classification of fossil eggs.[23]

- Paleontologist Bill Clemens alerted Jack Horner and Bob Makela to the presence of unidentified dinosaur fossils in Bynum, Montana. Horner visited the town and recognized the remains as belonging to a duck-billed dinosaur. While in town the owner of a local rock shop, Marion Brandvold, showed him some tiny bones. Horner identified them as baby duck-bill bones. Horner also knew that this was an important find and convinced Brandvold to let him study her fossils at Princeton University.[24] The fossil embryos were returned to Bynum a few years ago and are now on display at the Two Medicine Dinosaur Center.

- Karl Hirsch disputed Romer and Price's claim to have discovered a Permian hard-shelled egg, since the fossil in question didn't show evidence for the calcite that should have composed the shell. Hirsch found enough phosphorus in the object's outer layer to propose that the fossil was actually an egg, with a leathery shell.[14]

- Erben and others found isotope ratios of Carbon and Oxygen in French dinosaur eggs similar to those found in Mongolian dinosaur eggs by Folinsbee and others in 1970. The ratios are indicative of a diet of C3 plants and hot living conditions.[22]

- Jim Haywood and others were studying the nests of ground-nesting gulls buried by the Mount St. Helens eruption. They found that the volcanic ash was acidic enough to dissolve most of the eggshell in only two years.[25]

- Sarkar found isotope ratios of Carbon and Oxygen in Indian dinosaur eggs similar to those found in Mongolian dinosaur eggs by Folinsbee and others in 1970. The ratios are indicative of a diet of C3 plants and hot living conditions.[22]

Early to mid-1990s

- Russian paleontologist Konstantin Mikhailov brought attention to Zhao's classification system for egg fossil in the English language scientific literature.[26]

21st-century paleontology

- Steve Etches, Jane Clarke, and John Callomon reported the discovery of eight clusters of ammonite eggs in the Lower and Upper Kimmeridge Clay of the Dorset Coast in England. The eggs are subspherical to spherical in shape. Some are isolated but some were also found in association with the shells of perisphinctid ammonites. They were interpreted by the researchers as ammonite eggs sacks and are the best preserved specimens of such known to science. The parents of the egg sacks are thought to be two local ammonite genera co-occurring with the eggs, Aulacostephanus and Pectinatites.[27]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Carpenter (1999); "First Discoveries", page 1.

- 1 2 3 Carpenter (1999); "First Discoveries", page 4.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); page 128.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); page 129.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); pages 129–130.

- 1 2 Carpenter (1999); "First Discoveries", page 5.

- 1 2 Carpenter (1999); "First Discoveries", page 6.

- ↑ Carpenter (1999); "Reason 3. Eggshell Too Thin, Eggshell Too Thick", page 253.

- ↑ Carpenter (1999); "First Discoveries", pages 6–7.

- 1 2 Carpenter (1999); "United States", pages 15–16.

- ↑ Carpenter (1999); "United States", page 16.

- ↑ Carpenter (1999); "First Discoveries", pages 1–2.

- ↑ Carpenter (1999); "First Discoveries", page 2.

- 1 2 3 Carpenter (1999); "Evolution of the Reptile Egg", page 43.

- ↑ Carpenter (1999); "India", page 27.

- ↑ Carpenter (1999); "India", page 28.

- ↑ Carpenter (1999); "Canada", page 19.

- 1 2 Etches, Clarke, and Callomon (2009); "Introduction", page 205.

- ↑ Carpenter (1999); "United States", pages 16–18.

- ↑ "Tools of the Trade", Carpenter (1999); page 125.

- ↑ "Tools of the Trade", Carpenter (1999); page 131.

- 1 2 3 "Tools of the Trade", Carpenter (1999); page 132.

- ↑ "Growth of the Modern Classification System", Carpenter (1999); pages 148-149.

- ↑ Horner (2001); "History of Dinosaur Collecting in Montana", page 56.

- ↑ Carpenter (1999); "How to Fossilize an Egg", page 112.

- ↑ "Growth of the Modern Classification System", Carpenter (1999); page 149.

- ↑ Etches, Clarke, and Callomon (2009); "Abstract", page 204.

References

- Carpenter, Kenneth (1999). Eggs, Nests, and Baby Dinosaurs: A Look at Dinosaur Reproduction (Life of the Past). Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33497-7.

- Etches, S., Clarke, J. and Callomon, J. (2009). Ammonite eggs and ammonitellae from the Kimmeridge Clay Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Dorset, England. Lethaia, Vol. 42, pp. 204–217.

- Horner, John R. (2001). Dinosaurs Under the Big Sky. Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87842-445-8.

- Mayor, Adrienne (2005). Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11345-9.