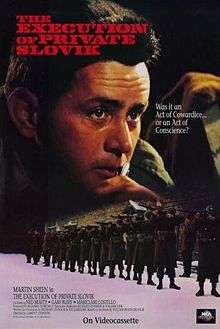

The Execution of Private Slovik

| The Execution of Private Slovik | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Lamont Johnson |

| Produced by | Richard Dubelman |

| Written by |

William Bradford Huie Lamont Johnson Richard Levinson William Link |

| Starring |

Martin Sheen Mariclare Costello Ned Beatty Gary Busey Charlie Sheen |

| Music by | Hal Mooney |

| Cinematography | Bill Butler |

| Edited by | Frank Morriss |

| Distributed by | Universal Studios |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 120 Mins |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $180,000 |

The Execution of Private Slovik is a nonfiction book by William Bradford Huie, published in 1954,[1] and an American made-for-television movie that aired on NBC on March 13, 1974. The film was written for the screen by Richard Levinson, William Link and by Lamont Johnson who was the director, the film stars Martin Sheen,[2] and also features Charlie Sheen in his second film in a small role.[3]

Plot

The book and the film tell the story of Private Eddie Slovik, the only American soldier to be executed for desertion since the American Civil War. The film starred Martin Sheen as Private Slovik, a performance for which he received an Emmy Award nomination for Best Lead Actor in a Drama. Sheen said he did not think actors should be compared, and made it clear he would refuse the award. Many critics and viewers consider this to be one of Sheen's finest performances. Among the other Emmy Award nominations, the film was named for "Outstanding Special". The film also won a Peabody Award.

Development

In 1960 Frank Sinatra announced that he would produce a film adaptation of The Execution of Private Slovik, with the screenplay to be written by Albert Maltz, who was one of the Hollywood 10 blacklisted after they refused to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in the McCarthy era. This announcement evoked tremendous outrage, with Sinatra accused of being a Communist sympathizer. As Sinatra was campaigning for John F. Kennedy for President, the Kennedy campaign became concerned and ultimately prevailed upon Sinatra to cancel the project.[4]

In 1949, a Pentagon source revealed to Huie a European graveyard containing the remains of unidentified American soldiers. Huie's investigation identified Slovik's name and grave. Huie's account of Slovik is an example of his style of reporting and his tendency to anger Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had authorized the execution as commander of the Allied Forces, and who tried to stop publication of the book. Award-winning filmmaker Richard Dubelman acquired the film rights from Sinatra. Some years later, Dubelman persuaded Universal Studios to help him produce it as a television movie.

Historical accuracy

The military service record of Eddie Slovik, which is now a public archival record available from the Military Personnel Records Center, provides a detailed account of the actual execution of Slovik which took place in 1945 and it was upon this that most of the film was based. The execution in the film, including the missed shots by the firing squad which led to Slovik dying slowly on the firing post over a course of five minutes, are deemed totally accurate as compared to the actual execution. A slight dramatic license does occur in the final scene, as there is no evidence that the priest attending Slovik's execution shouted "give it another volley if you like it so much" after the doctor indicated Slovik was still alive.[5]

In popular culture

- The 1963 World War II film The Victors includes a scene depicting the Christmas Eve execution of a GI deserter modeled after Slovik, accompanied by a Sinatra Christmas recording.

- In Kurt Vonnegut's 1969 novel Slaughterhouse-Five, Billy Pilgrim finds an abandoned copy of Huie's book about Slovik and reads through it while in a waiting room.

- The Canadian TV film Execution tells a similar tale, based on the execution of Canadian soldier Harold Pringle for desertion in World War II.

See also

References

- ↑ "The Execution of Private Slovik" by William Bradford Huie, ISBN 1594160031

- ↑ The New York Times

- ↑ The New York Times

- ↑ Scott Allen Nollen, The Cinema of Sinatra, pp. 214-216 ISBN 1-887664-51-3

- ↑ Archival service record of Eddie Slovik, National Personnel Records Center.