Steyning Line

| Steyning Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Legend | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

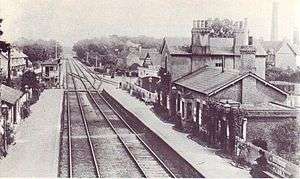

The Steyning Line (also known as the Adur Valley Line) was a railway line that connected the West Sussex market town of Horsham with the once bustling south-coast port of Shoreham-by-Sea, with connections to Brighton. Covering 20 miles (32.19 km), the line closed on 7 March 1966, a casualty of the Beeching Axe.[1]

History

Historical context

As with the Cranleigh Line just to the north, the Steyning Line was a consequence of the fierce competition between the London and Brighton Railway (LBR) and the London and South Western Railway (LSWR), for lucrative south coast traffic. In 1844 the LSWR's engineer, Robert Stephenson, drew up plans to construct a line through the Mole Gap, where the River Mole cuts through the North Downs, to Chichester via Horsham and Dorking. At Horsham, a branch was to head south to the then important port of Shoreham-by-Sea. Hearing of this proposed encroachment into its territory, the LBR acted quickly in promoting its own scheme for a line to Horsham and Shoreham. The London and Brighton (Steyning Branch) Railway Act received royal assent on 18 June 1846 and the company's engineer, R. Jacomb-Hood, was instructed to survey the line. Later that year the LBR merged with the London and Croydon Railway, creating the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LBSCR).[1][2]

In late 1847 the LBSCR's incentive to proceed rapidly with the line was removed when, amidst growing financial difficulties and the economic recession, the LSWR ordered a halt to its plans for the line. This, and the LBSCR's own financial problems, led to Jacomb-Hood being instructed to down tools, which prompted his resignation in January 1848. As the LBR's chairman, Samuel Laing, explained to a Parliamentary Inquiry in 1858, new lines "were abandoned during the crisis of 1847 and 1848 when Railway property was almost irretrievably ruined and it was absolutely impossible to raise money."

Although the LBSCR did proceed to connect Horsham with its main line between London and Brighton in 1848, it was eight years before it revisited a line to Shoreham.

Steyning Railway Company

In 1856 a group of local residents clubbed together to form the "Steyning Railway Company" with the intention of bringing to fruition the LBSCR's plans for a line through Steyning. A meeting was held at The White Horse Hotel in Steyning on 23 June, at which it was agreed that representatives of the company would approach the LBSCR with an offer to construct the line and lease it to the LBSCR. Terms were agreed that the railway company would pay an annual rent equivalent to 4% of the construction costs. Jacomb-Hood, who had been re-engaged by the LBSCR, was once again dispatched to survey the route. His report, delivered on 21 August, projected costs of £39,000 for a line on the west bank of the River Adur with a station at Applesham Farm near the recently opened Lancing College. It also indicated the traffic that the line could hope to carry.[2]

Before the company could begin construction, it had to raise at least 75% of the total expenditure. By 4 December it was still £7,890 short and approached the LBSCR to see whether it would contribute the outstanding balance. In order to determine whether such expenditure was justified, the LBSCR's chairman, Leo Schuster, and another director, Admiral Laws, personally examined the route on 12 December. Their report concluded against helping the company, stating "that the project was not of sufficient importance as should induce [the LBSCR] to deviate from the terms which they have already undertaken to enter into." This refusal led to the company abandoning their project, although without ruling out re-examining it again in the future.

Two rival schemes

One year later, new proposals were published for a line through Steyning, following the line put forward by Stephenson in 1844 for the LSWR. According to a memorandum published in Steyning on 5 September 1857 by John Ingram, the company secretary of the Steyning Company, a new enterprise called the "Shoreham Horsham and Dorking Railway Company" would promote an independent scheme supported by local landowners and residents. The new company engaged the services of Joseph Locke as chief engineer and Thomas Brassey as principal building contractor, both giants in their respective fields.[2]

Hearing of the new proposals, the LBSCR reacted by applying for Parliamentary authorisation for a new line from Shoreham-by-Sea to Steyning and Henfield with an option of an extension to its Mid-Sussex Line at Billingshurst. At the same time, the Shoreham Horsham and Dorking Railway Company applied to Parliament for authorisation of its route.

In order to determine which line should proceed, a Parliamentary Inquiry was held to determine their respective merits. Amongst the witnesses was Walter Barsteller, a magistrate and director of the Mid-Sussex Railway, who explained that the reason why the LBSCR was putting forward its own route was "the probability of the extension of the proposed line towards Guildford". This was confirmed by another magistrate, William Cory, who said that from Billingshurst the preferred route to Guildford was via Loxwood. The outcome of the Inquiry was that the LBSCR's line was approved and that proposed by the landowners was rejected.

Construction

Following the authorisation, the LBSCR decided to change the route of the line since just to the north a connection from Horsham to Guildford, the Cranleigh Line was now likely to be realised. Therefore, a route was chosen which deviated just north of Partridge Green to join the Mid-Sussex line near the southern end of the Horsham to Guildford line in the parish of Itchingfield, instead of going towards Billingshurst. Jacomb-Hood was again dispatched to survey this new route, a task which he had completed by summer 1859 when construction was initiated by the contractor, Mr Firbank. The first section, between Shoreham and Partridge Green,opened on 1 July 1861.[2]

A few days prior to the opening, the Government Inspector of Railways, Colonel Tyler, carried out an inspection of the line, testing in particular the strength of several bridges across the River Adur. In order to test the bridge at Beeding near the cement works four engines with their tenders were placed on it. Following the successful inspection, the Colonel and his party adjourned to The White Horse in Steyning.

In order to connect the Steyning Line with the Mid-Sussex and Cranleigh Lines two spurs were planned by Jacomb-Hood. From the triangular junction at Itchingfield, one would lead south to join the Mid-Sussex Line, while the other, 0.5 miles (0.80 km) long, would be constructed near Christ's Hospital at Stammerham Junction (also known as Itchingfield South Fork) which would allow through running to Guildford and Shoreham or Portsmouth without the need to reverse.

Operations

1861 - 1899

The LSWR's control of the railway network around Guildford ensured that the 0.5 miles (0.80 km) long spur remained little used, with few scheduled services. The LBSCR therefore decided to close it from 1 August 1867 amid concerns that the LSWR might take advantage of it to seek greater access to the south coast. No sign of it remains as the area has been ploughed over.

After the opening of the second phase of the line on 16 October 1861,[3] the daily service between Brighton and Horsham consisted of four stopping trains and one express. The frequency was increased, leading to the doubling of the line between Itchingfield Junction and Horsham during 1878-1879. Fortunately Jacomb-Hood had foreseen this eventuality and had ensured that all bridges were capable of carrying two tracks. This frequency of services was to the detriment of engine drivers and firemen, who went on strike in 1867 to call for a maximum 10-hour working day or a run of 150 miles (241.40 km). Engine drivers earned at most seven shillings per day whilst firemen were on four shillings and sixpence.

Itchingfield Junction was the location of the line's first accident on 11 August 1866 when two passenger trained collided resulting in one fatality.[2]

Traffic consisted mainly of agricultural produce, with goods being sent to the Brighton and Steyning markets and for auction. After the line opened Steyning's weekly market relocated from the High Street to a field adjacent to the railway station, and cattle, sheep, poultry and other produce were transported to and from it for more than a century. Examples of what was being delivered can be drawn from the records of inward freight at Steyning during 1874 and 1875; from Littlehampton 10 sacks of maize, from Brighton 10 sacks of wheat, from Horsham 14 bundles of timber, from Lancing 2500 bricks and 5 tons of beach pebbles and from Arundel one consignment of cement.

In addition to normal passenger workings, excursions began operating soon after the line to Partridge Green had been opened. One of the first was in July 1861 to Portsmouth; the fare was two shillings and there were 185 passengers on the service. Another excursion followed in August, to Crystal Palace via Hove.

1900 - 1965

Passenger traffic

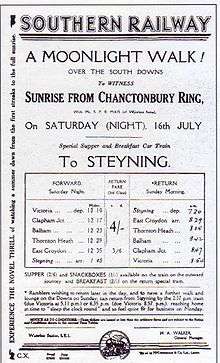

From 1923 the line became part of the Southern Railway following the grouping under the Railways Act. The line continued to be alive during summer weekends with a variety of excursions to Brighton and Hove from places as far afield as Wolverhampton, Banbury, Oxford and Reading, via Guildford and Horsham. During the football season specials took supporters to see Brighton and Hove Albion when they were playing at home. The Southern Railway promoted use of the line by ramblers and nature-lovers, such as scheduling late-night and early-morning services to observe the sun rising.[2]

On 31 October 1946 the Southern Railway announced a scheme to electrify the line, but this was abandoned following nationalisation in January 1948. The line now fell under the aegis of the Southern Region of British Railways. One of the first changes made was the end of the old method of counting passenger numbers. Whereas previously a system of "clearing" was employed whereby the revenue from a passenger's ticket was redistributed to the railway companies in proportion to the distance travelled on their line, this changed to a system of "global accounts" whereby each station in a British Railways (BR) region submitted to its line manager monthly returns of all business conducted.

Statistics of passenger tickets issued and collected show a steady rise in passenger traffic from 1948 to 1965, the year prior to closure. In 1948, 58,086 tickets were sold and 90,076 collected, ten years later these figures had risen to 106,110 and 126,272 and by 1965, they were 120,016 and 140,129 respectively. Although there was a slight decline in traffic in the early 1960s, this reflected a similar dip which had occurred 12 years previously and was modest when compared with the subsequent increase in numbers.

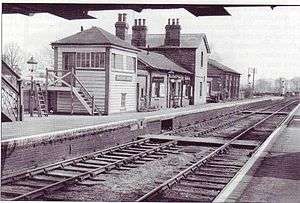

On Saturday 7 October 1961 a group of senior boys attending Steyning Grammar School organised an exhibition in the waiting room at Steyning station that celebrated the line's 100th anniversary. Both the station and signalbox were decorated in bunting to mark the occasion and trains carried special headboards.

Freight traffic

Until 1926 the line transported milk in 17-gallon churns, but this was switched to road haulage during the General Strike of that year. Farmers realised how much more convenient it was to use road transport which collected the churns directly from their farm and took them directly to their destination. Once the strike ended the milk traffic remained on road thereby depriving the railway of a major source of freight. This pattern was to be repeated during the strike of 1955 when more freight traffic, particularly coal, was diverted to road, much of it never to return. The freight losses contributed to British Rail's decision to close goods yards on the line as elsewhere on the rail network.[2]

Nevertheless, the line continued to serve two important industrial enterprises - the cement factory at Beeding and the brickworks at Southwater. The cement works received gypsum from Robertsbridge and coal from Dover, whilst once a week cement was transported to the British Portland Cement depot at Southampton via Shoreham and the South Coast main line. In 1960, for example, the cement works received 7000 coal wagons, 2300 gypsum wagons and 100 wagons of general stores; it sent out 7670 cement wagons and 240 flints wagons. Traffic continued beyond the line's closure until 1981 via a single line linking the works with the South Coast main line. The cement works closed in 1991 after more than 100 years of operations at Beeding.

Itchingfield Junction was the site of the last accident on the line as well as the first. Early in the morning of 5 March 1964, a goods train from Brighton to Three Bridges that had been diverted via Steyning overran the signal before the junction and collided with a down goods from Three Bridges to Chichester traversing the junction. The two crew on the up trains, apparently asleep possibly due to diesel fumes, were killed.

War years

As with the Cranleigh Line, the value of the line was fully realised during the two world wars when it acted as a conduit for men and munitions to the port of Newhaven. During the Second World War it was particularly convenient for access to Wiston House, Field Marshal Montgomery's headquarters near Steyning, which Winston Churchill visited towards the end of June 1940. It also provided access to Martin Lodge on Station Road at Henfield, which was used by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police; the 1st Canadian Infantry Division had a large encampment close to the airfield at Shoreham and on the playing fields of Lancing College.[2]

Decline and closure

The line's days were effectively numbered following the publication in 1963 of a report by the British Rail Chairman, Richard Beeching, which put forward a vision of a smaller and more efficient rail network. Entitled "The Reshaping of British Railways", the report advocated the closure of numerous lines and railway stations, including the Steyning Lines which, it was claimed, "carried in 1962-3 fewer than 5,000 passengers weekly."

Passenger traffic surveys

The closure of the line was based on figures taken from surveys of the number of originating passengers, carried out in November 1962 and July 1963. They measured traffic over two weeks, one during summer and the other during winter. They counted only passengers who purchased tickets at Steyning Line stations and not inward traffic in the shape of tickets collected from passengers alighting at stations. Had the two forms of traffic been taken into account, the survey would have revealed that on average 12,615 passengers travelled the line (both up and down) over the course of seven days during winter and 12,649 during summer. A significant proportion of the traffic, at least 1,000 journeys, was made up of schoolchildren. A further survey was carried out during half-term week in November 1964 following the change from steam to diesel traction on the line. Without the schools' traffic the survey showed a fall in passenger numbers to 9,225, a perceived loss of traffic that was to play a role in the decision to close the line.[2]

BR also examined season ticket sales. In 1948, 993 quarterly and long-term season tickets were sold: this had increased to 1,628 by 1959, but declined to 1,215 in 1965. One author has explained this decline by the dissuasive effect that the 1963 closure proposal would have had on passengers, and the fact that cheap-day returns would have been cheaper than seasons for those working a five-day week.

Closure proposal

In 1963 BR submitted to Ernest Marples, the Conservative Minister of Transport, a proposal to close the line. The next two years saw a public enquiry take place into the proposed closure and the obligatory Transport Users' Consultative Committee Report to the Minister.[2]

TUCC enquiry

The notice of proposed closure gave, as required by the Transport Act 1962, an address to which objections could be sent. 289 such objections were received and a public enquiry was called for Wednesday 26 February 1964 in Steyning chaired by Captain E.H. Longsdon R.N. (Ret'd). Objectors argued that the replacement of trains with buses would lead to increased travel times; for example, the additional time spent travelling between Bramber and Brighton during the 40-week school year would amount to the equivalent of 34 eight-hour working days. The recommendation of the Transport Users' Consultative Committee for the South East Region (TUCC) was that replacement buses would not alleviate the hardship caused by the line's closure. The line therefore remained open while the Minister undertook further enquiries.[2]

The Ministry of Transport therefore contacted BR to see if the line's losses which had already been reduced by the introduction of diesel units, could be reduced still further by increasing rail fares and by closing Bramber station. BR rejected any suggestion that economies could be made, stating that fares would have to be increased to 6d per mile (i.e. doubled) and all cheap day fares withdrawn.

Labour election

The Labour victory in the 1964 General Election saw a new Minister of Transport. In September 1965 he gave fresh authorisation for the closure of the line. He made this decision on the basis of a cost/revenue analysis (excluding freight revenue) which showed that the saving that would be made by closure was £173,200 for steam operation of the line, reduced to £43,200 if diesel units were introduced. One author estimates that the real saving made was actually a mere £14,000 since the track and signalling costs had been overestimated and took into account the main line between Itchingfield Junction and Horsham. He goes on to suggest that the line might in fact have been in profit due to overestimation of the costs of the permanent way and failure to consider converting the line to single-track working.[2]

1965 passenger survey

In a last-ditch attempt to save the line, the parish councils along the Adur Valley initiated a passenger card survey to provide an updated picture of traffic on the line. Fifteen hundred postcard-sized cards were distributed to passengers over a two-week period in October 1965. The scheme did not receive BR's official authorisation, but staff in station booking offices and parish councillors and commuters helped in the distribution of the cards, which had to be posted back to be recorded. In the event, 450 cards were returned and the results passed on to the local MP, Henry Kerby, who contacted Barbara Castle, Fraser's replacement as Minister of Transport. She replied on 16 March 1966 stating that she had considered the evidence and thought it was necessary to lay on extra services for passengers travelling at peak times. This would be done by varying the closure decision to include a condition that replacement bus services should be provided. Provided by Southdown Motor Services, the buses were sparsely patronised and eventually withdrawn. They had been introduced on the mistaken assumption that rail commuters would automatically switch to bus transport to travel long distances, whereas in the event only those travelling to Shoreham or Brighton used them. What actually transpired was revealed in a survey conducted in 1968, which showed that former rail users had arranged to share cars with friends or colleagues in the short term before eventually acquiring their own cars, taking early retirement or moving closer to their workplaces.

Closure decision

The axe was finally to fall in 1966 when it was clear that the new Labour administration would not reverse the closure policies put in place by the previous Government. As reported by the West Sussex Gazette of 10 February: "a meeting between the Railways Board and the Ministry of Transport last Wednesday seemed certain to result in putting off yet again the fateful deed, but a firm decision to go ahead with the closure came in the late afternoon...So brings down the curtain on a service that undoubtedly was 'borderline' if it should be closed or not. Certainly those who used the line regularly fought hard to save it, and even the Railways Board admitted to many misgivings as to whether their decision was the right one in all the circumstances."[2]

After 18 months of diesel working, passenger services were withdrawn from Monday 7 March 1966. The last train was on the Sunday evening, the 2128 from Brighton to Horsham. The track was lifted soon afterwards and the signalboxes demolished, with the stations going the same way in 1969. Partridge Green station and goods yard were let to industrial concerns and were eventually sold.[1]

The line today

Steyning Bypass

The closure resulted in a build-up of traffic on the A283 through Steyning, Bramber and Upper Beeding, notably heavy freight traffic from the Port of Shoreham. This led to calls for the construction of a bypass. The idea of a bypass linking the A2037 with the A283 to the north-west of Steyning had already been floated in 1962 and had been included in the West Sussex Village plan for the three communities involved. The route of the bypass would have avoided the railway line, requiring merely a bridge over King's Barn Lane in Steyning. However, with the closure of the line, the County Council proposed re-using the trackbed between Bramber and Steyning (about 1 mile (1.61 km)), a cheaper alternative that would cost £3 million. This was accepted by the Ministry of Transport and funding was granted.[2]

Downs Link path

In 1984, the local authorities along the route, working with other authorities and the Manpower Services Commission, established the Downs Link, a 30 mile long footpath and bridleway connecting the North and South Downs National Trails. The Link was opened on 9 July 1984 by the Mayor of Waverley, Anne Hoath, at Baynards station; it subsequently received a commendation in the National Conservation Award Scheme jointly organised by The Times newspaper and the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors.[4]

Retrospective

Although initially conceived as a conduit for services to the south coast, the worth of the Steyning Line was ultimately restricted to the small villages that it served. That its full potential was never realised can be explained by three interlinked factors. Firstly, the through connection between Brighton and Guildford was rendered difficult by the inconvenient timetabling of connections. Passengers changing at Horsham from a Cranleigh Line service to a Steyning Line service and vice versa usually had a tiresome wait before their connection arrived.[5] For example, the 1964-65 British Rail timetable reveals that a passenger taking the 0625 from Brighton would arrive in Horsham at 0728 with the next service to Guildford was 25 minutes later. Worse off was the passenger arriving in Horsham at 1221 to find out that the connecting train had departed 12 minutes earlier. The timetabling in this case is particularly difficult to understand as the service was scheduled to wait 10 minutes at Cranleigh due to congestion at Guildford.[6]

The second factor was the limited service which could be operated on the Cranleigh Line, mostly single track, which resulted in timetabling constraints.[7] Doubling of the track and reinstatement of the south spur would have gone some way to alleviating this problem and allow fast or semi-fast services. However, given the state of the economy after the Second World War, such investment was never a realistic possibility for perceived railway backwaters such as the Cranleigh and Steyning Lines. This links to the third factor, the perception by British Rail managers, who failed to appreciate the potential usefulness of the lines if co-ordinated effectively. Once Beeching had announced his programme of closures, it was taken as a given that the lines would close and services were gradually run down.[8]

Notes and references

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (1982). Branch Lines to Horsham. Midhurst, West Sussex: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-0-906520-02-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Buckman, James (2002). The Steyning Line. Seaford, East Sussex: S.B. Publications. ISBN 978-1-85770-254-5.

- ↑ Oppitz, Leslie (2001). Lost Railways of Sussex. Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-85306-697-9.

- ↑ West Sussex County Council. "Downs Link Route Guide" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ↑ Buckman 2002, p. 77.

- ↑ Buckman 2002, p. 33.

- ↑ Buckman 2002, p. 32.

- ↑ Buckman 2002, pp. 32-33.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Steyning Line. |

- Barnes, Philip (2001). The Steyning Line Rail Tour. Hove, East Sussex: Philip Barnes.

- Bathurst, David (2004). Walking the Disused Railways of Sussex. Seaford, East Sussex: S.B. Publications. ISBN 978-1-85770-292-7.

- Buckman, James (2002). The Steyning Line and its closure. Seaford, East Sussex: S.B. Publications. ISBN 1-85770-254-9.

- Carter, Tony (1996) [1992]. To the Railway Born: Reminiscences of Station Life, 1934-92. Wadenhoe, Peterborough: Silver Link Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-947971-79-3.

- Cockman, George (1987). Steyning and the Steyning Line. Steyning: Wests Printing Works.

- Course, Edwin Alfred (1973). The Railways of Southern England: The Main Lines. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd. ISBN 0-7134-0490-6.

- Course, Edwin Alfred (1974). The Railways of Southern England: Secondary and Branch Lines. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd. ISBN 0-7134-2835-X.

- Gray, Adrian (1975). The Railways of Mid-Sussex (Locomotive Papers No. 38). Tarrant Hinton, Nr. Blandford, Dorset: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-175-0.

- Hodd, H.R. (1975). The Horsham - Guildford Direct Railway (Locomotion Papers No. 87). Tarrant Hinton, Nr. Blandford, Dorset: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-170-X.

- Mitchell, Victor E.; Smith, Keith A. (1987) [1982]. Branch Lines to Horsham. Midhurst, West Sussex: Middleton Press. ISBN 0-906520-02-9.

- Nisbet, Alistair F. (January 2008). "A Wasted Opportunity". BackTrack. 22 (1): 41–43.

- Oppitz, Leslie (2001). Lost Railways of Sussex. Newbury, Berks: Countryside Books. ISBN 978-1-85306-697-9.

- Vallance, H.A. (February 1953). "To Brighton through the Shoreham Gap". Railway Magazine. 99 (622): 75–82, 90.

- Welbourn, Nigel (2000) [1996]. Lost Lines: Southern Region. Shepperton: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 0-7110-2458-8.

- White, H.P. (1987) [1976]. Forgotten Railways: South-East England (Vol. 6). Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-946537-37-2.

- White, H.P. (1992) [1961]. A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Southern England (Volume 2). Nairn, Scotland: David St John Thomas. ISBN 978-0-946537-77-8.