David Pendleton Oakerhater

| David Pendleton Oakerhater | |

|---|---|

|

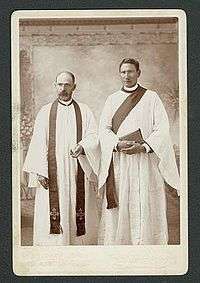

Oakerhater in 1881 | |

| Deacon and Missionary | |

| Born |

ca. 1847 Indian Territory |

| Died |

31 August 1931 Watonga, Oklahoma |

| Venerated in | Anglican Communion |

| Feast | 1 September |

David Pendleton Oakerhater (b. ca. 1847, d. August 31, 1931), also known as O-kuh-ha-tuh and Making Medicine, was a Cheyenne Indian warrior and spiritual leader, who became an artist and Episcopal deacon. Imprisoned in 1875 after the Indian Wars at Fort Marion (now Castillo de San Marcos), Florida, Oakerhater became one of the founding figures of modern Native American art. Later he was ordained as a deacon in the Episcopal Church in the United States of America and worked as a missionary in Oklahoma. In 1985, Oakerhater was the first Native American Anglican to be included in the book of Lesser Feasts and Fasts of the Episcopal Church.

Early life

Born in the 1840s in the Indian Territory (later the U.S. state of Oklahoma) to Sleeping Wolf (father), and Wah Nach (mother), Oakerhater was the second of three boys. His childhood name was Noksowist ("Bear Going Straight"), and he was raised as a traditional Cheyenne. His older brother was Little Medicine, and his younger brother was Wolf Tongue.[1]

Oakerhater is believed by some to have been the youngest man to complete the sun dance ritual (his Cheyenne name, Okuh hatuh, means "sun dancer").[2] He participated in his first war party (military raid) at age 14 against the Otoe and Missouri tribes,[1] and became a member of his tribe's "Bowstring Society" (one of five military societies).[1] He later participated in actions against United States federal and state militia forces. His first engagement with white settlers was at the Second Battle of Adobe Walls, in which 300 Native American warriors from various tribes, angered by settlers' poaching of buffalo, cattle grazing, and theft of horses, attacked a small trading village used by poachers.[1] The battle, led by Comanche leader Isa-tai and Chief Quanah Parker, triggered United States government response in the form of the Red River War of 1874-75. Oakerhater may also have participated in the Battle of Washita River and the Sand Creek massacre.[2]

Oakerhater married Nomee (translated as "Thunder Woman") in 1872. She died in 1880. They had four children, all of whom died young. Oakerhater also married, had at least one child, and divorced, a second woman, Nanessan ("Taking Off Dress").[1]

Fort Marion prisoner

In the Red River War of 1874 and 1875, the United States government attempted to pacify Native American warriors on the Southern Plains, fighting a series of skirmishes until the militants were exhausted by lack of food and supplies. The warriors, including Oakerhater, surrendered in 1875 at Fort Sill near what is now Lawton, Oklahoma. A group of 74 were selected from there and another location, all without trial, for imprisonment in Florida. Oakerhater was in a group chosen for being the eighteen farthest right in a line-up by a US Army colonel who had been drinking and was running out of time before nightfall. Some among the eighteen had nothing to do with the insurrection.

The army assigned First Lieutenant (later Captain) Richard Henry Pratt to transport the prisoners to an old Spanish fort, the Castillo de San Marcos (then known as Fort Marion), near Saint Augustine. Shackled together, they were taken across country on foot, by wagon, train (most had never before seen a train), and steamboat.[1] Many initially thought they would be executed. At least two attempted suicide; one was later shot and killed attempting to escape, and another died of pneumonia.[3]

Captain Pratt supported assimilated of American Indians into European-American mainstream society. He thought they needed to abandon their cultures and religions and learn the various practices of America's dominant white culture to survive: English, wage work, Christianity, literacy, mainstream education, and so on. The practice of forced assimilation, now criticized as cultural genocide, was considered progressive by its practitioners of the time.[4] Many European-Americans considered Native Americans to be enemies and murderers who should be killed, imprisoned, or defeated through force. Pratt's superior, General Philip Sheridan, dismissed Pratt's beliefs as "Indian twaddle".[1]

Conditions at the old fort were initially very poor: prisoners slept on the floor of their cells facing a central open-air courtyard. Several died in the first weeks.[1] Pratt quickly improved conditions, obtaining army uniforms, removing the prisoners' shackles, setting them to work building a new residential shed, and procuring bedding. Later, as trust developed on both sides, Pratt convinced his superiors to allow the Indians to carry nonoperational rifles, perform guard duty, obtain outside employment collecting and selling sea beans and other tourist items, have passes to visit the town on Sundays to attend church, and camp unsupervised on nearby Anastasia Island.[1]

Pratt, who offered to resign his military post if the experiment failed, appointed Oakerhater First Sergeant of the prisoners, with a duty to organize morning military drills, ensure hygiene and dress code, choose assistants for Captain Pratt, and oversee the prisoners in Pratt's absence. Pratt and his wife also arranged for volunteer teachers who were vacationing in Florida from across the United States to instruct the prisoners in English, carpentry, and other subjects. They allowed the Indians to conduct a mock buffalo hunt.[5]

In return the prisoners educated townspeople and tourists in archery, and made handicrafts and drawings to sell. Aware for their part of the nature of Pratt's experiment, the prisoners took pride in their work and martial discipline, eager to demonstrate that they could master white Americans' cultural and military practices. They took longer to overcome other cultural barriers, such as discomfort with being taught by women. The first summer Pratt arranged for their families to visit them from the Indian Territory. Within two years of arrival at Fort Marion, Oakerhater was proficient in English, and was regularly writing letters to townspeople he had befriended. That year nineteen of the prisoners were released, in exchange for accepting scholarships for education on the East Coast.[1]

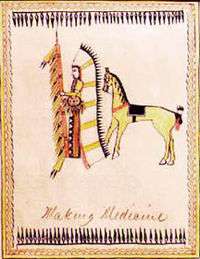

Ledger art

One of Pratt's experiments was to provide art supplies and instruction to the prisoners. They drew most of their art in pen in ledger books. Somewhat abstract in style and depicting nostalgic memories of scenes from daily life, their art draw inspiration from earlier Plains Indian hide painting, which included personal narratives and winter counts, calendar chronicles of tribal events. Typical subjects included community dances, hunts, courting, and events at the fort, as well as self-portraits depicting scenes before their imprisonment. The ledger art was a popular item for tourists to purchase. Through his art, Oakerhater gained the attention of Mrs. Alice Key Pendleton, to whose daughter he had given one of his drawing books.[1]

Oakerhater was the first and one of the most prolific, artists in the group. Oakerhater's drawings are considered by critics to be sophisticated in composition and subject content. These artworks are highly collectible today. He often signed his works "Making Medicine," a non-literal English translation of his Cheyenne name, Sun Dancer, which the military had assigned him upon his arrest.[1] Other times he would sign with a glyph of a dancer in a sun dance lodge to represent himself.[6] The Smithsonian Institution has a collection of the Fort Marion artists online.[7]

Episcopal affiliation

In 1877 an Episcopal deaconess, Mary Douglass Burnham, began to make arrangements to sponsor the remaining prisoners, including Oakerhater, to serve as church sextons and continue education. In April 1878 all of the prisoners were released. Burnham arranged funding from Alice Key Pendleton and her husband, Senator George H. Pendleton, to bring Oakerhater, as well as his wife Nomee, to St. Paul's Church in Paris Hill, New York, along with three other ex-prisoners who each had separate sponsors.[1] The church's priest, Reverend J.B. Wicks, took charge of Oakerhater's education on matters of agriculture, Scripture, and current events, and welcomed him as part of his family. Oakerhater, along with his three companions from Fort Marion, became popular among townspeople. They made and sold various items, including handmade bows. Within six months Oakerhater agreed to be baptized and was confirmed shortly after. He chose the biblical Christian name David and adopted the last name Pendleton in honor of his sponsors.[1] In 1878, Oakerhater was baptized at Grace Episcopal Church in Syracuse and ordained a deacon at that same church in 1881. Captain Pratt, encouraged by the success of his former prisoners at Paris Hill and some at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute for Negroes (now Hampton University), lobbied the federal government for funds to open schools for Indian children. Senator Pendleton pushed a bill through Congress to found the first school in 1879 at the unused Carlisle Barracks in central Pennsylvania. It was named the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

In July, 1880 Nomee died in childbirth. The next year Oakerhater's young son Pawwahnee died. Both were buried in the cemetery in Paris Hill. Oakerhater was ordained an Episcopal deacon in July, 1881.[1] According to sources, O-kuh-ha-tah’s son, Frederick; wife, Millie; and another child, who died at birth, are buried in the church cemetery in Paris Hill, New York.

Missionary

After Oakerhater was ordained a deacon, Pratt sent him on a trip to Indian Territory and Dakota Territory to recruit students for Carlisle, where Pratt had been appointed superintendent. Traveling with Reverend Wicks to the Darlington Agency near what is now El Reno, Oklahoma, Oakerhater used his connections and influence to encourage local Cheyenne to attend Episcopal religious services. Remaining in the area, he traveled to the Anadarko Agency (near present-day Anadarko, Oklahoma) for Sunday services, spending weekdays visiting and caring for ill members of various tribes.[1]

In 1882 Oakerhater married Nahepo (Smoking Woman), who adopted the English name Susie Pendleton. They had two children, who both died young. Nahepo died in 1890, at age 23.[1]

In 1887 Oakerhater began work at newly built missions in Bridgeport, and in 1889 at the Whirlwind Mission near Fay, seventeen miles west of Watonga, Oklahoma. The mission, built in 1887, was on the Dawes Act allotment land of Chief Whirlwind, one of the negotiators of the Treaty of Medicine Lodge.[8] As at other Indian schools being established in the United States, many of Whirlwind's students suffered from poverty and related diseases. Many suffered from trachoma and conjunctivitis.

Their parents, whose lives had been disrupted by colonialism, warfare, forcible relocation, and the breaking up of tribal lands for allotment, were exploited by local non-Indians who wanted to profit from their newly assigned land grants. Uprooted, the families would often camp out near the schools to be with their children and provide a safer environment. Oakerhater's school and mission were under pressure both from locals, who saw the mission as a threat to their attempts to exploit the Native American population, and from others at the local and national level, who deplored the poor conditions there.[1]

Oakerhater retired from Whilrwind with a pension in 1918 but continued to preach, serving as a Native American chief and holy man.[9] He moved briefly to Clinton, Oklahoma and then to Watonga, where he lived until his death in 1931.[1]

Saint

After Oakerhater died, the Episcopal Church did not sponsor significant mission work in Watonga, Oklahoma for more than thirty years. In the early 1960s, an Episcopalian family that had moved to the area placed an ad in a local paper to announce a meeting in their home. Native Americans who had known Oakerhater met with the family and worked with them to revive his old mission.[9]

In 1985 the Episcopal Church designated Oakerhater as a saint, thanks in part to the years of work and research by Lois Carter Clark, a Muscogee Creek scholar.[10] On September 1, 1986, the first feast was held in his honor at the Washington National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., with his descendants and delegations from Oklahoma invited to the celebration. In 2000 the Saint George Church of Dayton, Ohio dedicated a large stained glass window in its chapel depicting Oakerhater, and a smaller window bearing his glyph signature.[9]

St. Paul's Cathedral in Oklahoma City dedicated a chapel to St. Oakerhater. The congregation of St. Paul's commissioned Tlingit glass artist, Preston Singletary, to create a stained glass window featuring Oakerhater's glyph. It replaced a church window destroyed in the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. The Oakerhater Guild of St. Paul's was organized in partnership with Whirlwind Mission of the Holy Family and sponsors dances, tribal outreach, and a vacation Bible school for children in Watonga.[11]

In 2003 the Whirlwind Church obtained at a new permanent site in Watonga, where it dedicated the Oakerhater Episcopal Center in September 2007.[12] The site is used for powwows, a sweat lodge, classes, and an annual Cherokee Dance in Oakerhater's honor.[1][12]

Grace Episcopal Church in Syracuse, NY is a national shrine to Saint O-kuh-ha-tah. On Saturday, April 16, 2005, a Native American Celebration was held there to honor Cheyenne Saint David Pendleton Oakerhater (O-kuh-ha-tah/Making Medicine), the first Native American saint of the Episcopal Church, and Oneida Marcia Pierce Steele, teacher of both Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) cultural traditions and Christian beliefs. Grace Church’s celebration included a day-long cultural festival, followed by holy eucharist and a blessing of new memorial stained-glass windows. Roberta Whiteshield-Butler, great-granddaughter of O-kuh-ha-tah, created the drawings for the windows. Rose Viviano of Rose Colored Glass fabricated the windows which were installed in September 2004 and blessed by Bishop Adams at the April 2005 celebration. Saint O-kuh-ha-tah’s descendants travelled from Oklahoma and Texas to attend the celebration at Grace Episcopal Church in Syracuse, New York. Prior to the celebration, O-kuh-ha-tah descendants (great-great grandson, Jack Southmeth; granddaughter Elizabeth Whiteshield; great-granddaughter Kim Whiteshield; and great-great granddaughter Starr Whiteshield) travelled to St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Paris Hill (near Utica) to visit O-kuh-ha-tah’s home church and the graves of their ancestors.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 K.B. Kueteman. "From Warrior to Saint: The life of David Pendelton Oakerhater". Oklahoma State University.

- 1 2 "Oakerhater, David Pendleton". Oklahoma State University.

- ↑ Hilton Crowe (December 1940). "Indian Prisoner-Students at Fort Marion: The Founding of Carlisle Was Dreamed in St. Augustine". the Regional Review (United States National Park Service).

- ↑ Stanford L. Davis. "Captain Richard Henry Pratt, 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldiers, Founder of the Carlisle School for Indian Students: His Motto, "Kill the Indian, save the man"". Buffalo Soldier.

- ↑ Brad D. Lookingbill (2006). War Dance at Fort Marion:Plains Indian War Prisoners. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3739-8.

- ↑ "Letter from David Pendleton Oakerhater to Mrs. Mary Burnham, September 2, 1881". Oklahoma State University.

- ↑ "Fort Marion Artists", Smithsonian Institution, accessed 4 Dec 2008

- ↑ Lois Clark (1985). "Whirlwind Cemetery and David Pendleton (O-kuh-ha-tah):God's Warrior". State of Oklahoma.

- 1 2 3 Anne E. Rowland. "David Oakerhater Window". St. George's Church of Dayton, Ohio.

- ↑ Anderson, Cokie G. "From Warrior to Saint: The Journey of St. David Pendleton Oakerhater", Oklahoma State Digital Library. 2006 (retrieved 26 Jan 09)

- ↑ "St. Oakerhater Guild." St. Paul's Cathedral. 2009 (retrieved 26 Jan 09)

- 1 2 Carla Hinton (2007-09-01). "Oakerhater Center dedication set for Sept. 8 in Watonga". Daily Oklahoman.

External links

Media related to David Pendleton Oakerhater at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to David Pendleton Oakerhater at Wikimedia Commons- "David Oakerhater window", St. George Church Official Website, Dayton, OH

- St. Oakerhater Guild, St. Paul Cathedral, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

- "From Warrior to Saint:the Journey of David Pendleton Oakerhater". Oklahoma State University library. - Library project on Oakerhater

- Portions of the Book of Common Prayer in Cheyenne, Oakerhater collaboration, Anglican Communion

- David Pendleton Oakerhater at Find a Grave