Sitok Srengenge

| Sitok Srengenge | |

|---|---|

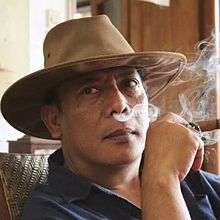

Sitok Srengenge in 2015 | |

| Born |

Sitok Sunarto August 22, 1965 Dorolegi, Purwodadi, Central Java |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Years active | 1985–present |

Sitok Srengenge (born 22 August 1965) is an Indonesian poet, actor, and dramatist. Born Sitok Sunarto in Purwodadi, Central Java, he became interested in literature at a young age and was heavily influenced by his village's strong oral tradition. When he moved to Jakarta to complete his university studies, he became involved with the Bengkel Teater under Rendra. Sitok remained with the company for almost a decade, appearing in several plays as he refined his literary style. His first poetry collection, Persetubuhan Liar, was published in 1992.

Sitok has since published multiple poetry collections, including a bilingual work titled On Nothing and a trilogy of revised editions known collectively as Tripitakata, as well as a novel and serial. He has presented his poetry in such countries as the Netherlands and Germany, and participated in writers workshops in Hong Kong and Iowa. His poems, noted for their "laconic, muscular, and musical" poetic phrase,[1] have been adapted to music in a variety of genres. In 1999, Asiaweek described Sitok as "Indonesia's best young poet".[2]

Biography

Early life

Sitok Srengenge was born Sitok Sunarto in Dorolegi, Purwodadi, Central Java, on 22 August 1965.[3] Though the villagers did not support their children attending school, and elders would chase prospective students away, they maintained a strong oral tradition that Sitok credits with influencing the sonic qualities of his poetry.[4] As a youth he was active in theatre,[5] and by junior high school he had begun to write poetry.[3] In a 2004 interview, he stated "All I knew was that writing those words that lingered in my head made me happy".[3]

Despite the resistance against education, Sitok obtained a scholarship which allowed him to complete his elementary and secondary school studies in the provincial capital of Semarang.[4][3] He graduated from Senior High School 1, Semarang, in 1985.[6]

Theatre and first collection

In 1985, Sitok moved to Indonesia's capital, Jakarta, to study at the Faculty of Art and Literature of the Jakarta Teacher Training Institute.[lower-alpha 1][5] There he became involved with Bengkel Teater under the poet-cum-dramatist Rendra, who gave him the name Sitok Srengenge, which translates from Javanese as "the only sun".[4][lower-alpha 2] In his ten years with Bengkel Teater, Sitok practiced poetry, monologues, and acting, and appeared in several of the troupe's plays.[3]

Sitok published his first poetry collection, Persetubuhan Liar, in 1992.[lower-alpha 3] Funded by the singer-songwriter Iwan Fals, this collection was intended as a counterpoint to the rise in religious literature which had become popular in Indonesia in the early 1990s.[4]

In the mid-1990s Sitok became an independent artist, acting under directors such as Ikranegara (Jam Berapa Sekarang) and Ratna Sarumpaet (Pesta Terakhir);[5] he has remained active into the 2010s, portraying the Mahabarata warrior Karna in a 2011 play by Goenawan Mohamad.[7] He also established his own theater troupe, Teater Matahari, as well as the Keranjang Sampah Kebudayaan ("Cultural Wastebin") discussion forum.[6]

Short stories by Sitok were included in the short story anthology Para Pembohong (The Liars) in 1996. Publication of the anthology was supported by Sitok's organization Gorong-Gorong Budaya, meant to encourage and support pro-democracy artists.[5] Sitok was a founding member and one of the directors of the Utan Kayu Arts Community Center, serving as the director of its literary biennale and editor of its journal Kalam during the 1990s and 2000s.[8][9] Beginning in 2007, he served as a curator for the Salihara cultural center[10] until his resignation in 2013.[11]

As a student, Sitok was involved in pro-democracy rallies against President Suharto. In the lead-up to Suharto's 1998 resignation, he would often attend underground rallies and discussions, reciting verses of poetry. None of these works had been anthologized by 2006.[4] Sitok was one of the participants in the 1995 Istiqlal International Poetry Reading conference, which focused predominantly on Islamic poetry, and several of his poems were included in its publication The Poet's Chant.[4][12][13] Bulgarian translations of his works were published in Chants of Nusantara that year.[14]

Subsequent collections

In 1999, Asiaweek wrote that Sitok "is considered Indonesia's best young poet [and] often thought ... as contributing to the 'reawakening' of Indonesian literature".[2] The magazine selected him as "one of twenty leaders for the Millennium in society and culture in Asia".[8] The translator and Indonesianist Harry Aveling, in his 2001 anthology Secrets Need Words, described Sitok as a "pioneer" leading poets out of "the fear that froze the poets of the eighties".[15]

In 2000, Sitok published Anak Jadah (Bastard), a collection of poems described by Yenni Kwok of the Sunday Morning Post as "a statement about the confusion of his generation". Explaining the title, Sitok stated that "Tradition and modernisation met in a careless encounter" producing "a generation of cultural bastards".[4] A second poetry collection, Nonsens, was published later that year by the Kalam Foundation in collaboration with the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies, Ford Foundation, and Adikarya IKAPI Foundation. The collection contained thirty-five works, as well as several illustrations by Agus Suwage.[16]

Sitok published his debut novel, Menggarami Burung Terbang (Salting a Flying Bird), in 2004. The work follows a group of common villagers (the Javanese wong cilik) in the period following the coup attempt of 1965.[3] Pamela Allen, writing in Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, found the novel to have a "rich, dense blend of realist prose in Indonesian, Javanese mythology and Javanese language", making it unprecedented in works of Indonesian literature which deal with the subject matter.[17] She argued that Sitok used local colour (warna lokal) not as a simple backdrop to a nationalist discourse, but rather to grant "real insight into local ways of thinking and interpreting the world".[18]

Sitok released a bilingual volume of his poetry, On Nothing, at the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival.[19] The poems in this second collection ranged from "gentle and romantic" to "drenched in erotic images and metaphors".[4] The edition, published by Sitok's own publishing house Kata Kita, contains Indonesian and English versions of poems from his first four poetry collections, translated by four writers: Nukila Amal, Hasif Amini, Margaret Glade-Agusta, and Lauren Bain.[19][20] of The Jakarta Post found "both structured and unstructured poetry" and "themes connected to the human condition, such as love, motherhood, childbirth and racism" in the collection.[19]

A trilogy of poetry collections, titled Tripitakata, was released in 2013. Its first volume, Gembala Waktu dan Madah Pereda Rindu, contained poems written by Sitok while still in senior high school and university, up through 1989.[21] The second volume, Kelenjar Bekisar Jantan dan Stanza Hijau Muda, was expanded on the previous collections Persetubuhan Liar and Kelenjar Bekisar Jantan with poems written between 1986 and 1991.[22] The third, Anak Badai dan Amsal Puisi Banal, contained the poems of Anak Jadah as well as other poems written between 1986 and 1991.[23] In August 2015, Sitok released another poetry collection, Ereignis dan Cinta yang Keras Kepala, which contained fifty poems written between 2010 and 2014.[24]

Sitok has attended several writers workshops, including at the University of Iowa (2001) and Hong Kong Baptist University (2005).[8] He has read his poems at the Indische Festival in the Hague, the Winternachten Festival in the Hague, the University of Leiden, and the University of Hamburg.[13]

Style

In a 1999 interview with Asiaweek, Sitok compared writing to boxing, with essays and other prose as shadowboxing and poetry as "real" boxing.[2] When reciting his poetry, he prefers rote memorization over reading published or written editions – something unusual among Indonesian poets.[5] Sirikit Syah of The Jakarta Post describes him as having "a powerful voice and impressive stage rhythm" and of being "a master of lexicon".[25] Krassin Himmirsky, who translated several of Sitok's poems into Bulgarian, found his "poetic phrase ... laconic, muscular, and musical", with a universal message.[1]

Regarding the writing process, Sitok has stated that "There are poems within me. They are just there."[5] He composes his poetry in his mind, and is reluctant to write them unless they are completed.[5] He may produce as few as two poems a year.[5] He says that, although he may occasionally be influenced by politics, he tries to separate civic involvement and writing.[4]

Impact and critical reception

Sitok's work has been adapted to various media. In 2011, Dian HP produced Delapan Komposisi Cinta (Eight Compositions of Love), a concert for Ubiet Raseuki, using lyrics taken directly from the poems of Sitok and Nirwan Dewanto.[26] In 2012 she released Semesta Cinta, an album of art songs based on Sitok's poetry.[27] The Australian writer Jan Cornall released a jazz album, Singing Srengenge, based on the poet's work; Sitok's works have also been adapted by Denise Jannah and David Kotlowy.[28]

Sitok's poetry has been compared to the work of numerous other poets, both Indonesian and non-Indonesian, including Pablo Neruda,[4] Chairil Anwar, Iwan Simatupang, and Sitor Situmorang.[1] Cornall describes Srengenge's work as "deeply spiritual in the true sense of the word ... where the sensuality of longing, the beauty of sorrow, and the wisdom of deeply felt observation becomes the language of the soul".[29] Himmirsky finds Sitok's poems to include "the true values of life, its pulsating dynamism and wisdom. ... [Readers] are deeply moved by his affection for his beloved, for his parents, for the human race."[14] The translator John McGlynn writes that Sitok "explores topics with a depth and maturity not only rare among his peers, but also with a vocabulary and clarity that few other poets can match".[30]

Personal life

Sitok is married to Farah Maulida.[5] The couple have a daughter, Laire Siwi Mentari. She is a novelist, publishing her debut work Nothing but Love in 2004;[4] by 2009 it had sold more than 40,000 copies. She has published a further novel, Aphrodite, and in 2009 was working on a short story collection.[31]

The family lives in Bantul, Yogyakarta. Their home, construction of which began in 2006, sits on 18,000 square metres (190,000 sq ft) of land and holds six buildings: the main house, a joglo style pavilion, a public library, private office, communal kitchen, and guest house. The open plan house itself is an "eclectic" design, "fus[ing] ethnic and art deco styles" and incorporating antique building materials from throughout Java. The landscaping itself maintains natural surroundings, avoiding artificial gardens.[32]

Bibliography

Poetry collections

- Persetubuhan Liar (1992)

- Kelenjar Bekisar Jantan (2000?)

- Anak Jadah (2000)

- Nonsens (2000)

- On Nothing (2005)

- Gembala Waktu dan Madah Pereda Rindu (2013)

- Kelenjar Bekisar Jantan dan Stanza Hijau Muda (2013)

- Anak Badai dan Amsal Puisi Banal (2013)

- Ereignis dan Cinta yang Keras Kepala (2015)

Prose

- Menggarami Burung Terbang (novel; 2004)

- Trilogi Kutil (1984)

- Cinta di Negeri Seribu Satu Tiran Kecil (essay collection; 2012)

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Institut Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan Jakarta, now the State University of Jakarta (Universitas Negeri Jakarta)

- ↑ Such name changes are common in Javanese culture, where they signify one's entrance into adulthood (Kwok 2006, p. 7).

- ↑ Asiaweek notes that the title translates literally as Extramarital Sex, but in 1999 the poet preferred the translation Wild Be One (Tesoro 1999, p. 43) Another possible translation of the title is Wild Coupling (Kwok 2006, p. 7)

References

- 1 2 3 Himmirsky 2000, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Tesoro 1999, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Prihandono 2004.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kwok 2006, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Syah 1997a.

- 1 2 Rampan 2000, p. 425.

- ↑ Setiawati 2011.

- 1 2 3 HKBU 2005.

- ↑ Gramedia 2008, p. 197.

- ↑ Junaidi 2007.

- ↑ Tempo 2013.

- ↑ Rampan 2000, p. 426.

- 1 2 Srengenge 2000, inside cover.

- 1 2 Himmirsky 2000, p. 8.

- ↑ Aveling 2001, pp. 188–189.

- ↑ Srengenge 2000, pp. 6, 11–12.

- ↑ Allen 2011, p. 2.

- ↑ Allen 2011, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Hara 2005.

- ↑ Srengenge et al. 2005, pp. 6–11, 347.

- ↑ Srengenge 2013a, p. 4.

- ↑ Srengenge 2013b, p. 8.

- ↑ Srengenge 2013c, p. 6.

- ↑ Srengenge 2015, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Syah 1997b.

- ↑ Hamdani 2011.

- ↑ Wahid 2011.

- ↑ Srengenge 2015, p. 106.

- ↑ Cornall 2005, p. 341.

- ↑ Srengenge 2000, rear cover.

- ↑ Malik 2009.

- ↑ Setiawati 2012.

Works cited

- Allen, Pamela (2011). "Menggarami Burung Terbang: Local Understandings of National History". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 167 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003599. ISSN 0006-2294.

- Aveling, Harry (2001). Secrets Need Words: Indonesian Poetry, 1966-1998. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-89680-216-2.

- Cornall, Jan (2005). "On Eating and Singing On Nothing". On Nothing. Depok: Kata Kita. pp. 340–342. ISBN 978-979-3778-19-8.

- Dua Puluh Cerpen Indonesia Terbaik 2008 [Twenty Best Indonesian Short Stories, 2008] (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Gramedia. 2008. ISBN 978-979-22-3449-7.

- Hamdani, Sylvia (2 June 2011). "Making Poetry Sing, In the Name Of Love". Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 2 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- Hara, Chisato (11 October 2005). "Sitok Srengenge Launches a Poetry Anthology". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Himmirsky, Krassin (2000). "Editor's Note". Nonsens [Nonsense]. Jakarta: Kalam Foundation. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-979-95480-5-4.

- Junaidi, A. (23 July 2007). "Salihara Promises New Cultural Oasis". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- Kwok, Yenni (12 February 2006). "Rhyme of the Times". Sunday Morning Post. Hong Kong: 7.

- Malik, Candra (31 August 2009). "My Jakarta: Laire Siwi Mentari, Writer". The Jakarta Globe. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Prihandono, Omar (27 June 2004). "Poet Sitok Not Afraid to Say It Like It Is". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Rampan, Korrie Layun (2000). Leksikon Susastra Indonesia [Lexicon of Indonesian Literature]. Jakarta: Balai Pustaka. ISBN 978-979-666-358-3.

- Setiawati, Indah (20 November 2011). "Karna, His Identity and Complexity". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Setiawati, Indah (3 June 2012). "Sitok Srengenge's True Sanctuary". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- "Sitok Srengenge Mundur dari Komunitas Salihara" [Sitok Srengenge Resigns from the Salihara Community]. Tempo. 3 December 2013. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- Tesoro, Jose Manuel (5 February 1999). "Sitok Srengenge". Asiaweek. Hong Kong: 43.

- Srengenge, Sitok (2000). Nonsens [Nonsense]. Jakarta: Kalam Foundation. ISBN 978-979-95480-5-4.

- Srengenge, Sitok (2013a). Gembala Waktu dan Madah Pereda Rindu [The Shepherd of Time and the Eulogy to Ease Longing]. Jakarta: KataKita. ISBN 978-979-3778-70-9.

- Srengenge, Sitok (2013b). Kelenjar Bekisar Jantan dan Stanza Hijau Muda [The Rooster’s Glands and the Pale Green Stanza]. Jakarta: KataKita. ISBN 978-979-3778-71-6.

- Srengenge, Sitok (2013c). Anak Badai dan Amsal Puisi Banal [Son of the Storm and Proverbs of Banal Poetry]. Jakarta: KataKita. ISBN 978-979-3778-72-3.

- Srengenge, Sitok (2015). Ereignis dan Cinta yang Keras Kepala [Ereignis and Stubborn Love]. Depok: Kata Kita. ISBN 978-979-3778-74-7.

- Srengenge, Sitok; Amal, Nukila; Amini, Hasif; Glade-Agusta, Margaret; Bain, Lauren (2005). On Nothing. Depok: Kata Kita. ISBN 978-979-3778-19-8.

- Syah, Sirikit (26 January 1997a). "Sitok: 'There are Poems within Me'". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta.

- Syah, Sirikit (4 May 1997b). "Romantic Love is in the Air at Literary Reading". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta.

- "Visiting Writers 2005". Hong Kong Baptist University. 2005. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- Wahid, Ismi (6 September 2011). "Menafsir Sastra Lewat Alunan Nada" [Interpreting Literature through the Melody of Tones]. Tempo (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.