Siege of Gaeta (1806)

| Siege of Gaeta | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Third Coalition | |||||||

Gaeta's historic quarter from Monte Orlando | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 12,000 | 7,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,000 | 7,000 | ||||||

The Siege of Gaeta (26 February - 18 July 1806) saw the fortress city of Gaeta and its Neapolitan garrison under Louis of Hesse-Philippsthal besieged by an Imperial French corps led by André Masséna. After a prolonged defense in which Hesse was badly wounded, Gaeta surrendered and its garrison was granted generous terms by Masséna.

The 1806 Invasion of Naples by Napoleon's forces was provoked when King Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies joined the Third Coalition against Imperial France. The Kingdom of Naples was rapidly overrun by Imperial soldiers, but Hesse stubbornly held out at Gaeta. The garrison put up such fierce resistance that a large part of Masséna's Army of Naples was tied up in the siege for nearly five months. This prevented Masséna from sending reinforcements to quell an uprising that had started in Calabria as well as allowing the British to land an expeditionary force and score a victory at the Battle of Maida. However, because the British failed to relieve the garrison of Gaeta, the city was finally captured in mid-July after French artillery smashed gaps in the city's defences.

Background

By the late summer of 1805, the War of the Third Coalition was about to break out. Emperor Napoleon deployed 94,000 men to defend his possessions in Italy. Marshal André Masséna had 68,000 men in the main army, the satellite Kingdom of Italy added 8,000, and an observation corps of 18,000 kept an eye on the Kingdom of Naples.[1] Against Napoleon's empire, the Austrian army in Italy under Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen ranged 90,000 men.[2] Neapolitan army of King Ferdinand IV counted a mere 22,000 soldiers. Afraid that the French might invade his domain, the king concluded a treaty with Napoleon to remain neutral.[3] In exchange, the French agreed to evacuate Apulia in southern Italy. The treaty was ratified in Naples on 3 October.[4]

As soon as the ink was dry, the French observation corps abandoned Apulia and marched north to join Masséna's army. Immediately, Ferdinand and Queen Maria Carolina treacherously summoned two Coalition expeditionary forces to Naples. Lieutenant General James Henry Craig sailed from Malta with 7,500 British troops while General Maurice Lacy of Grodno (1740–1820) landed 14,500 Russian soldiers from Corfu.[5] A second source noted that 6,000 men under Craig and 7,350 under Lacy landed at Naples on 20 November 1805. By this time only 10,000 Franco-Italian troops observed the Neapolitan border.[3]

As Craig and Lacy prepared for an offensive into northern Italy, they were astounded to find that the Neapolitan army was not ready to join them. Without the assistance of their allies, Craig and Lacy were only strong enough to maintain a defensive posture. Meanwhile, the Kingdom of Naples belatedly drafted 6,000 men for military service by pressing jailed criminals into the ranks. In the meantime, a reinforcement of 6,000 Russians landed.[6] Napoleon's decisive victory at the Battle of Austerlitz on 2 December 1805 ended the Third Coalition.[7] After Czar Alexander I of Russia ordered Lacy to withdraw his force, Craig decided to evacuate the British corps also. Understanding that retribution would soon follow, the Neapolitan government was thrown into chaos.[8] The king knew that he had double-crossed Napoleon.[3]

Casting about for a good position to defend, Craig offered to hold the fortress of Gaeta. However, its governor, Prince Louis of Hesse-Philippsthal stubbornly refused to admit his men to the citadel. The British general then asked the Neapolitan government if he could land his troops at Messina in Sicily. This offer was rudely turned down. Ignoring this slight, Craig got his corps aboard ships on 19 January 1806 and sailed to Messina. The British soldiers waited on their naval transports in harbor until the king and queen finally allowed them to land on 13 February.[9]

Invasion

.jpg)

The French army under Masséna crossed the border on 8 February 1806, meeting little or no resistance.[10] King Ferdinand had already fled to Sicily on 23 January and Queen Carolina followed suit on 11 February.[11] On the Adriatic coast, a division under Giuseppe Lechi captured Foggia before turning west across the Apennines and reaching Naples. Masséna's main column rapidly arrived near Gaeta, about 40 miles (64 km) north of Naples. Since Hesse refused to surrender and the very strong fortress dominated the coast road, the French commander assigned Gardanne's division to blockade it. On 14 February, Masséna seized Naples with his remaining soldiers.[12] Napoleon had chosen his brother Joseph Bonaparte to replace Ferdinand and the new king made a triumphant entrance to the city the next day.[13] At this time, Joseph assumed control of the army. He put all troops in the vicinity of Naples under Masséna and his field army under Jean Reynier. Reynier soon left Naples and advanced to the south[12] with approximately 10,000 troops.[14]

On 9 March 1806 Reynier's force encountered 14,000 Neapolitans under Roger de Damas.[15] In the Battle of Campo Tenese the Neapolitans were routed, losing 3,000 soldiers, all their artillery, and their wagon train.[16] While Reynier pursued Damas' crippled force, a French corps under Guillaume Philibert Duhesme chased another body of Neapolitans.[17] The Neapolitan army fell apart during the retreat. The militia went home and most of the regulars deserted; only 2,000 to 3,000 regulars were evacuated to Sicily.[18] The high-handed behavior of French and allied soldiers soon provoked a serious revolt among the Calabrian peasantry. Typically, Imperial French soldiers were waylaid and killed. French commanders responded by attacking and burning villages, leading to an ugly cycle of atrocity and counter-atrocity.[19]

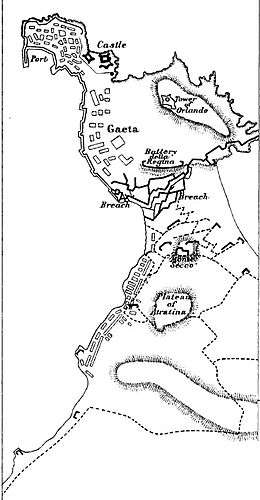

Forces

In 1806, Gaeta had a population of about 8,000 and possessed powerful fortifications. The city stood on a peninsula that jutted into the sea. Gaeta's landward approaches were defended by a 1,300 yards (1,189 m) long fortified trace that was three lines deep in places. The Breach Battery was 150 feet (46 m) above the sea, the Queen's Battery even higher, while the Tower of Orlando stood 400 feet (122 m) high. These works could concentrate a large volume of fire against any attacker.[20] Gaeta's garrison under Hesse counted 3,750 foot soldiers disposed in the following regiments, 3rd Battalion of the Presidio (990), 3rd Battalion of the Carolina (850), Prince (600), Val di Mazzara (600), Apulia Chasseurs (110), Val Demone (100), and Val Dinotto (100). There were also 400 volunteers in the garrison. The garrison also included 2,000 irregulars.[21] Many of the regulars were poor material, the scrapings of Neapolitan and Sicilian jails.[22]

The I Corps under Masséna consisted of two French infantry divisions under Generals of Division Louis Partouneaux and Gaspard Amédée Gardanne and two French cavalry divisions led by Generals of Division Julien Augustin Joseph Mermet and Jean-Louis-Brigitte Espagne. Partouneaux's division included the 22nd and 29th Line Infantry Regiments in the 1st Brigade and the 52nd and 101st Line in the 2nd Brigade. All regiments had 3 battalions. Gardanne's division had three battalions each of the 20th and 62nd Line in the 1st Brigade and one battalion each of the Corsican Legion and the 32nd Light Infantry Regiment plus the three-battalion 102nd Line in the 2nd Brigade. Mermet's division comprised the 23rd and 24th Dragoon Regiments in the 1st Brigade and the 29th and 30th Dragoons in the 2nd Brigade. Espagne's division was made up of a Polish regiment and the 4th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiment in the 1st Brigade and the 14th and 25th Chasseurs à Cheval in the 2nd Brigade. All cavalry units had four squadrons. The corps artillery included six 6-pound cannons, two 3-pound cannons, and five howitzers.[23]

Gaeta

Gaeta's commander Prince Hesse was an eccentric soldier of fortune. The general was short in stature and red-faced with an aquiline nose. Known for his hard drinking, he was also a good leader of men. He gained the respect of his poorly motivated soldiers by joking with them and showing outstanding personal courage. From the first days of the siege, he posted himself at the Breach Battery and announced that he would not quit until the siege was done. He also vowed to limit his drinking[22] to only one bottle a day. Referring to Karl Mack von Leiberich's surrender of Ulm, he famously yelled at the besiegers through a speaking-trumpet, "Gaeta is not Ulm! Hesse is not Mack!" When the French first arrived in the neighborhood on 13 February, they demanded that the fortress be handed over to them. When Hesse answered the request by firing a cannon, the French left an observation force in the area.[24]

The Siege of Gaeta began on 26 February 1806.[25] Masséna made a reconnaissance of the fortress and assigned General of Brigade Nicolas Bernard Guiot de Lacour to command the besiegers. Batteries were dug and armed with cannons obtained from the arsenals at Capua and Naples. The French siege lines were anchored on Monte Secco, which was 600 yards (549 m) from the fortress, and on the more distant Plateau of Atratina. On 21 March, the French formally summoned Gaeta to surrender. Hesse replied that his answer would be found in the breach, which is to say that the French would first have to batter a hole in the wall. But when the besiegers' guns opened fire they were quickly silenced by the 80 cannons that Hesse had trained on their new batteries. The French went back to work rebuilding their batteries, bringing up more cannons, and digging trenches closer to the defenses. On 5 April, Hesse refused another French summons. When the besiegers' cannons opened fire they were again rapidly put out of action by the superior weight of Gaeta's artillery.[26]

Realizing that Gaeta could not be cheaply taken, the French appointed General of Brigade Jacques David Martin de Campredon, an engineering expert, to direct the siege. In order to get close enough to blast a breach in the walls, the French began digging parallels into the ground in front of Monte Sacco. Because the soil was rocky, this process was difficult.[26] Meanwhile, Hesse was loath to mount sorties to destroy the French siege lines because the Neapolitan soldiers would frequently desert to the French. Hesse requested assistance from his government, but did not receive any right away because Admiral Sidney Smith was fully employed in supporting the guerilla war in Calabria.[27] At length, Smith's squadron arrived at Gaeta and dropped off food, four heavy cannons, and the partisan leader Michele Pezza, also known as Fra Diavolo. Smith also ordered some gunboats under Captain Richardson to stand by the fortress, a reinforcement which proved troublesome to the enemy.[27] Sometime in April, the Royal Navy landed Fra Diavolo and considerable force of irregulars near the mouth of the Garigliano. Their raid was successful at first but the partisans were finally scattered and Fra Diavolo made his way back to Gaeta. When Fra Diavolo was later implicated in a scheme to betray Gaeta, Hesse had him shipped back to Palermo in chains.[28]

Until the end of May, the French besiegers never had more than 4,000 men. But after that date they started to get heavily reinforced so that their numbers doubled by 28 June. On that day, Masséna took personal command of the siege. In the meantime, the garrison made sorties on 13 and 15 May, putting a few cannons out of action and carrying off some prisoners. By early June, the French had dug parallels within 200 yards (183 m) of the fortress and constructed batteries for 100 cannons. All the work was done under murderous defensive fire from Gaeta.[29] French General of Brigade Joseph Sécret Pascal-Vallongue was mortally wounded in the head on 12 June and died on the 17th.[30]

On 28 June, the French opened fire with 50 heavy cannons and 23 mortars. This time, Gaeta's artillery was unable to suppress the besiegers' fire, which dismounted some guns and caused numerous casualties. By 1 July, the bombardment had blown up three powder magazines in the fortress, but Hesse refused to give up. There was a lull, while the French sapped closer to the walls.[31] On the 3rd, 1,500 reinforcements to the garrison arrived by sea. That evening Richardson's vessels bombarded the French lines without result. At 3:00 AM on 7 July, the French opened fire again with 90 cannons. The mutual bombardment inflicted great damage to both attackers and defenders. But the greatest loss to the defenders occurred when Hesse was badly wounded by a bursting shell on 10 July and had to be evacuated by sea. His replacement was Colonel Hotz, an officer of only ordinary talent. Worried that their supply of shells would run out, the French offered a bounty for the recovery of unexploded ordnance. On the 11th, Masséna's artillery commander General of Brigade François Louis Dedon-Duclos begged the marshal for a pause in the bombardment, lest they run out of ammunition. Hoping that the loss of Hesse would demoralize Gaeta's garrison, Masséna ordered the fire to continue.[32]

On 12 July 1806, two breaches began to be seen in Gaeta's walls, one at the Breach Battery on the left and one under the Queen's Battery on the right. Surrender was demanded, but Hotz refused. The barrage continued and on the 15th a French engineer officer crept far enough forward to note that the west breach could be attacked. By 16 July, Masséna had heard about the French defeat at Maida and was anxious to capture Gaeta. There remained only 184,000 pounds of gunpowder and less than 5,000 shot, a three-day supply.[32] By this time, the French had 12,000 troops on hand in the infantry divisions of Partouneaux and Gardanne, with the cavalry divisions of Espagne and Mermet in support.[25] Despite the ammunition shortage, the bombardment dragged on, widening the breaches. Normally, the commander of the besiegers kept the time of the final assault on a fortress a secret from the defenders. But Masséna intended to overawe Hotz with his deliberate preparations for attack. On the morning of 18 July in full view of the defenders, the French massed a force of grenadiers and chasseurs under General of Brigade François-Xavier Donzelot to attack the left breach, while voltigeurs led by Valentin assembled to assault the right breach. The French ostentatiously marched up supporting troops. Masséna's bluff had the intended effect when Hotz put up a white flag at 3:00 PM.[33]

Results

Because of its prolonged defense and because he needed to capture Gaeta quickly, Masséna granted lenient terms to Hotz. The garrison was allowed to sail away to Sicily on the promise not to fight against France for one year. The fortress and all its cannons, of which one in three were damaged, was given over to French control. An embarrassing incident occurred when a considerable body of the Neapolitan regulars deserted to the French. The French admitted losses of 1,000 killed and wounded, but they may have been twice that.[34] Out of a garrison of 7,000, the Neapolitans lost 1,000 killed and wounded plus 171 cannons.[25]

On 4 July 1806, a British expedition under John Stuart drubbed a French division led by Reynier at the Battle of Maida.[16] After the victory, Stuart and Admiral Smith decided to move south and mop up the French garrisons in Calabria. Thus, a chance was missed to interrupt the siege of Gaeta or to land at Naples in an attempt to overthrow Joseph's government. Gaeta's surrender freed Masséna's force for operations in Calabria. Stuart's triumph did, however, prevent a potential French invasion of Sicily and lengthened the Calabrian revolt. The French did not bring the region under control until 1807.[35]

Gaeta was turned into a duché grand-fief in the Napoleonic Kingdom of Naples with the French name of Gaete.[36] The duchy was awarded to finance minister Martin-Michel-Charles Gaudin on 15 August 1809.[37] After the collapse of the Joachim Murat's kingdom in the Neapolitan War, Gaeta was the last city to hold out. The 1815 siege lasted from 28 May to 8 August before the surviving 133 officers and 1,629 men of the Neapolitan garrison surrendered to Austrian General-major Joseph von Lauer.[38]

Notes

- ↑ Schneid, Frederick C. (2002). Napoleon's Italian Campaigns: 1805-1815. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0-275-96875-8.

- ↑ Schneid (2002), p. 18

- 1 2 3 Schneid (2002), p. 47

- ↑ Johnston, Robert Matteson (1904). The Napoleonic Empire in Southern Italy and the Rise of the Secret Societies. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 66–67. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ↑ Johnston (1904), p. 68

- ↑ Johnston (1904), pp. 71-72

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 217

- ↑ Johnston (1904), pp. 73-74

- ↑ Johnston (1904), pp. 74-76

- ↑ Schneid (2002), p. 48

- ↑ Johnston (1904), p. 84

- 1 2 Schneid (2002), p. 49

- ↑ Johnston (1904), p. 86

- ↑ Johnston (1904), p. 88

- ↑ Johnston (1904), p. 89

- 1 2 Smith (1998), p. 221

- ↑ Schneid (2002), p. 50

- ↑ Johnston (1904), p. 90

- ↑ Johnston (1904), pp. 92-96

- ↑ Johnston (1904), p. 106

- ↑ Schneid (2002), p. 175

- 1 2 Johnston (1904), p. 107

- ↑ Schneid (2002), pp. 173-174

- ↑ Johnston (1904), p. 108

- 1 2 3 Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. p. 222. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

- 1 2 Johnston (1904), p. 108-109

- 1 2 Johnstone (1904), p. 110

- ↑ Johnstone (1904), p. 113

- ↑ Johnston (1904), p. 114

- ↑ Timmermans, Dominique (2007). "L'Empire par ses Monuments: Chateau de Versailles" (in French). Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- ↑ Johnston (1904), p. 131

- 1 2 Johnston (1904), p. 132-133

- ↑ Johnston (1904), p. 134

- ↑ Johnston (1904), p. 135

- ↑ Schneid (2002), p. 55

- ↑ Velde, François (2011). "Napoleonic Titles and Heraldry: Duchés grands-fiefs". heraldica.org. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ Allégret, Marc. "Gaudin, Martin-Michel-Charles (1756-1841) Ministre des Finances, Duc de Gaete" (in French). napoleon.org. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 556-557

Coordinates: 41°12′39″N 13°34′17″E / 41.21083°N 13.57139°E