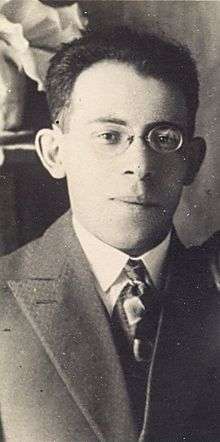

Shmuel Zytomirski

| Shmuel Zytomirski | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

16 September 1900 Warsaw, Poland |

| Died |

1944 Unknown |

| Cause of death | Unknown |

| Education | Teacher |

| Known for | Henio Zytomirski's father and a well-known figure at the Jewish community of Lublin before and during World War II. |

| Children | Henio Zytomirski |

Shmuel Zytomirski (Hebrew: שמואל ז'יטומירסקי, Polish: Szmuel Żytomirski; September 16, 1900 – 1944) was a well-known figure at the Jewish community of Lublin before and during World War II and the father of Henio Zytomirski. He died in The Holocaust at the end of the war, after almost all his family were killed by the Nazis. The letters Zytomirski had sent and received during the war document a lost struggle of a brave man who died shortly before the war ended. The information regarding the short life of his son Henio, who became an icon of the Holocaust in Poland, became known to the public from the father's letters. The circumstances of Shmuel Zytomirski's death remain mysterious and are unknown to this day.

Biography

Youth

Shmuel Zytomirski was born in Warsaw (now in Poland, but then in Imperial Russia) on September 16, 1900. His father, Ephraim (1880–1941), who was born in the little town of Medzhybizh (Polish: Międzybóż) in Podolia (now in Ukraine) was one of Hovevei Zion, a follower of the Mizrachi movement,[1] one of the Yavne School founders built in Lublin[2] and an active member in "benefit society" charity fund in Lublin. Shmuel's mother, Chaya Devora (née Melamed) (1882–1942), was born in Riga (now the capital of Latvia, but then in Imperial Russia). At the age of 16, Shmuel graduated cum laude from Krinsky[3] Jewish Gymnasium in Warsaw. During World War I the economic conditions in Warsaw became worse. In 1917 Zytomirski family moved to Lublin, hoping to improve their economical status.

Teacher and educator

Young Shmuel Zytomirski was a teacher in Tarbut school at the town of Bychawa. His attempts to immigrant from Poland to Land of Israel had failed. After completing a year of study at University of Vienna, he came back to Lublin in 1922 and continued to teach. He was an idealistic devoted teacher. Zytomirski had taught his students the best works of art of modern Hebrew poets and writers (Constitution Generation): Bialik, Tchernichovsky, Peretz and Frug. At his students' hearts he implanted the Zionist vision and the desire for leaving diaspora and aid the national renewal of the Jews in the land of Israel. While teaching he used various advanced pedagogical methods: plays, poetry, public declamation of pieces and trips out-of-town.[4]

Zionist leader

Zytomirski's best efforts were dedicated to Zionist activity, which had national and social orientation. He was the chairman of Poale Zion (Z.S.) party in Lublin.[5] Zytomirski and his party took actions in the community council and in the community committee for the poor and for the Zionist enterprises and institutions. Thanks to the efforts of Poale Zion (Z.S.) party, the community council allocated substantial funds for several important organizations - CYSZO (The Central Organization of Yiddish Schools), the Tarbut Hebrew school, the National Funds (JNF and Keren Hayesod), HeHalutz movement and Hapoel sport association (the first Hapoel club in Poland was founded in Lublin) - as well as for evening classes organized by Poale Zion (Z.S.) party. Thanks to the efforts of the Zionist parties, several rooms at the community house in 41 Krawiecka street were renovated and given to the Hakhshara Kibbutzim. These kibbutzim were the cores of Yad Mordechai and Negba kibbutzim in the land of Israel.[6]

Often Zytomirski and his party members participated in lectures and meetings which were held in towns near Lublin: Piaski (Lublin Province), Lubartow, Łęczna, Krasnik, Bychawa and Bilgoraj. Frequently there were district conferences of Poale Zion (Z.S.) party, in which representatives from the central committee in Warsaw were present.[3]

Zytomirski was a member of the Central Committee of the League for Working Eretz Israel. The league carried out an extensive explanatory and cultural activities. Famous people came to Lublin and lectured in the league's meetings: Zalman Shazar (Rubashov), the author Nathan Bistritzky (Agmon) and Eliyahu Dobkin.[7]

Zytomirski was a committee member of HeHalutz organization in Lublin.[8] He was also a member of the youth movement 'Dror' and its culture committee,[9] and attended the Executive Committee of the Tarbut Hebrew school in Lublin. In the 1930s Zytomirski was the organizer of the Lublin branch of HIAS welfare organization.[10]

Zytomirski and his son Henio

In the early 1930s Shmuel Zytomirski was married to Sara Oksman, who ran retail store to stationery. In 1933 their son Henio (in Hebrew: חיים) was born.

During Henio's childhood the situation of Jews in Poland became worse. In the neighbour country of Germany the Nazi regime was established, and in post-Pilsudski Poland anti-Semitism was increased. Over the window of Zytomirski family store Anti-Semite Poles had engraved the word ZYD (In polish: "Żyd"). In 1937 Shmuel Zytomirski wrote in a letter to his young brother Yehuda, who had immigrated to Land of Israel in that year:

...and I am very bothered by the question: What will be with my son when he grows up? I can already give him a report that there is no future for him in Poland, and I am already prepared to send him to Palestine in order to teach him there. Because indeed, all of my share from all my labor is my son, and I cannot imagine his future - even the near future - outside the borders of Palestine.

In accordance with his perception he registered his son to learn in Tarbut school, a Jewish and Zionist school in which the lessons were in the Hebrew language. Henio was not fortunated to enter the school gates. On September 1, 1939, the opening day of school, Nazi Germany invaded Poland and World War II had begun.

World War II period

Lublin Ghetto

With the establishment of Nazi regime in Poland, a Judenrat of 24 members was set up in Lublin. Zytomirski, a teacher by profession and Chairman of the Poale Zion movement in Lublin, was appointed by the Judenrat to be the manager of the post office at 2nd Kowalska Street. This role allowed him, apparently, to make contact with the Polish underground (which delivered him forbidden information and news[11]); to correspond with his young brother, Yehuda (Leon) Zytomirski, who had already immigrated to Land of Israel in 1937; to be in contact with Yitzhak Zuckerman and Zivia Lubetkin[12] from the Jewish resistance in Warsaw Ghetto and with Hashomer Hatzair people in Vilnius; and to correspond with Nathan Schwalb,[13] Director of the Jewish Agency offices and HeHalutz movement in Geneva, who was providing assistance to hundreds of youth movement activists in the Nazi occupation territories.

By order from the Nazi governor of Lublin district, all 34,149 Jews who lived then in the city were forced on March 24, 1941 to move to the ghetto that was established in Lublin. In March 1941, Zytomirski family moved to 11th Kowalska Street in the Lublin Ghetto. Shmuel Zytomirski's father, Ephraim, had died from typhus on November 10, 1941. Before his death he asked to be buried near the cemetery gates in order to be the first to witness the liberation of Lublin. The tombstone on his grave was smashed and destroyed in 1943 when the Nazis liquidated the new Jewish graveyard in Lublin.

Zytomirski didn't surrender to the harsh conditions in Ghetto Lublin and was a source of encouragement to his friends. For example, in December 1941 the Nazi Security Police (in Germany: Sicherheitspolizei SiPo) ordered the Judenrat in Lublin to collect from Lublin Jews all the woolen clothes they had in their possession and give it to the Germans. The Judenrat called to one hundred people and sent them to collect woolen clothes. Professor Nachman Korn and Shmuel Zytomirski went from house to house to collect woolen clothes for the Wehrmacht soldiers who fought in the Russian front. Zytomirski had tried to reassure the people and told them:[14]

Jews, give wool, because the salvation is about to come. If collecting clothes for the Germans on the front is needed, it means they are in big trouble...

Being a person who had seen matters from historical perspective, Zytomirski wrote a diary since the beginning of Nazi occupation. In his diary he recorded everything he had seen and heard. He kept the diary like the apple of his eye. His hope was that the diary would get to trustful hands and would serve as evidence of Nazi atrocities. With the death of Shmuel Zytomirski also his diary was lost.[15] The letters of him and of his father which remained after their death are poor substitutes for the lost diary. Reading the letters leads the reader through the loss route of the family and loss of Lublin Jewish community.

Sending Lublin Jews to extermination in Belzec

On March 16, 1942, the transports in freight trains from Lublin District to extermination camps began as part of "Operation Reinhard". Every day about 1,400 people were sent to camps. The German police and SS people supervised the transports. The Selection of the Jews took place in the square adjacent to the municipal slaughterhouse. The deportees were led on foot from the Great Synagogue (named after the Maharshal), which served as a gathering place for the deportees. Elderly and sick people were shot on the spot.[16] The rest were sent to the extermination camps, mainly to Belzec. Hundreds of Jews were shot dead in the woods on the outskirts of Lublin. A total of about 29,000[16] Lublin Jews were exterminated during March and April 1942. Apparently, among them were Shmuel Zytomirski's wife, mother and two of his sisters – Esther and Rachel – who were murdered then.

Majdan Tatarski Ghetto

On April 14, 1942 the transports ended. Zytomirski and his son Henio survived the selections of spring 1942, apparently thanks to a work permit (in German: J-Ausweiss) that Shmuel had. Along with the rest of the Jews who stayed alive in Lublin, they were transferred to another ghetto, smaller, that was established in Majdan Tatarski (a suburb of Lublin). Between 7,000 and 8,000 people entered this ghetto, although many of them did not have work permits. On April 22 the SS held another selection: about 2,500 to 3,000 people without work permits were taken initially to Majdanek and from there to Krepiec (Krępiec) forest which is about 15 km from Lublin. There they were shot to death.

From Majdan Tatarski ghetto Zytomirski sent (via Red Cross organization) a message to his brother Yehuda in the Land of Israel:

- - - Henio is with me.

On July 23, 1942 Zytomirski sent a letter from Majdan Tatarski ghetto to Nathan Schwalb in Geneve:

You must know how sad and lonely I am. If my dear wife and my devoted parents were alive, things were totally different. At this moment you are my only hope. That is why I expect to receive food packages from you as frequent as possible. In my solitude I hang all my hopes in you.

These words of Zytomirski, "in my solitude I hang all my hopes in you", were used by the Holocaust researcher, Prof. Avraham Milgram, as the title to his article about sending the food packages from Portugal to Jews who were in territories under Nazi occupation.[13]

The end of Lublin Jews

On 9 November 1942, the final liquidation of the Jewish Ghetto in Majdan Tatarski occurred. About 3,000 people were sent to the extermination camp Majdanek, including Zytomirski and his son Henio. Old people and children were sent immediately to the gas chamber. Nine year old Henio Zytomirski was also in this group.

Men and women who were capable to work were sent to forced labor camps in Lublin, such as Flugplatz (where the property of the murdered Jews was sorted and sent to Germany) and Sportplatz (where the forced labor prisoners built sports stadium for the SS people). Apparently, Zytomirski was transferred to the Sportplatz camp. From the camp he managed to send two last letters to the Zionist delegation in Constantinople. On 3 November 1943, the massive extermination of all remaining Jewish captives and prisoners in Majdanek and the other camps in Lublin District took place. This liquidation is known as "Aktion Erntefest", which in German means "Harvest Festival". On that day at Majadanek 18,400 Jews were shot to death in specially dug open pits. That murderous "operation" was the largest single execution in the history of the Nazi death camps. At the end of this killing operation, Lublin District was declared Judenrein, i.e., "free of Jews".

Mystery of his death

Surprisingly, Shmuel Zytomirski survived also this mass extermination. This is known according to a letter he had sent by courier from Lublin to the Zionist delegation in Constantinople on 6 January 1944. It is not clear from where exactly this letter was sent. The address on the letter was "7 Drobna Street". In that letter Zytomirski stated preliminary information about the mass killing at Majdanek in November 1943. That was his last letter. Only half a year later, on 24 July 1944, the city of Lublin was liberated by the Soviet Red Army. Shmuel Zytomirski did not survive the Holocaust; The circumstances of his death remain unknown. It is not known where he was hiding in the last days of his life, and whether he was betrayed or got sick and died.

See also

References

- ↑ Kantor Theodor Herzl, The 'Mizrachi' movement in Lublin, In: "Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: A Memorial Library of Countries and Communities - Poland Series: Lublin Volume", Jerusalem, 1957, p 449, in Hebrew

- ↑ Meisles, A.C., 'Yavneh' school. In: "Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: A Memorial Library of Countries and Communities - Poland Series: Lublin Volume", Jerusalem, 1957, pp. 579–580.

- 1 2 Zuckerman, Meyer. 'The Palestine labor movements'. In: "Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: A Memorial Library of Countries and Communities - Poland Series: Lublin Volume", Jerusalem, 1957, p. 411.

- ↑ Sheingarten, Noah. 'Profile of a teacher'. In: J. Adini (Ed.), Bychawa: A memorial to the Jewish community of Bychawa, Lubelska. Tel Aviv, 1969, pp. 243–245.

- ↑ Zuckerman, Meyer. 'The Palestine labor movements: Ze'ire Zion and Poale Zion (Z.S.)'. In: "Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: A Memorial Library of Countries and Communities - Poland Series: Lublin Volume", Jerusalem, 1957, pp. 401–406.

- ↑ Zuckerman, Meyer. 'The community in the years 1932-1939'. In: "Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: A Memorial Library of Countries and Communities - Poland Series: Lublin Volume", Jerusalem, 1957, pp. 373–376.

- ↑ Zuckerman, Meyer. 'The Palestine labor movements: The league for Working Eretz Israel'. In: "Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: A Memorial Library of Countries and Communities - Poland Series: Lublin Volume", Jerusalem, 1957, pp. 406–408.

- ↑ Korn, Nachman. 'The Zionist movement: HeHalutz'. In: "Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: A Memorial Library of Countries and Communities - Poland Series: Lublin Volume", Jerusalem, 1957, p. 389.

- ↑ Zuckerman, Meyer. 'The Movement for Working Eretz Yisrael, Chapter V: HaDror'. In: "Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: A Memorial Library of Countries and Communities - Poland Series: Lublin Volume", Jerusalem, 1957, pp. 410–412.

- ↑ Zuckerman, Meyer. "The Movement for Working Eretz Yisrael, Chapter I: Ze'ire Zion and Poale Zion (Z.S.)". In: "Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: A Memorial Library of Countries and Communities - Poland Series: Lublin Volume", Jerusalem, 1957, p. 405.

- ↑ Korn, Nachman. 'The last days of Bella', In: Bella Mandelsberg-Schildktaut, On the history of Lublin Jewry. Tel Aviv, 1965, p 43.

- ↑ Zariz, Ruth. 'Letters from haluzim in occupied Poland, 1940-1944'. The Ghetto Fighters' House, 1994, p. 147.

- 1 2 Milgram, Avraham (April 2007). In my solitude I hang all my hopes in you.... Moreshet. Broucure 83. p.94, in Hebrew

- ↑ Korn, Nachman. 'The last days of Bella', In: Bella Mandelsberg-Schildktaut, On the history of Lublin Jewry. Tel Aviv, 1965, p 44.

- ↑ Zuckerman, Meyer. 'The Movement for Working Eretz Yisrael'. In: "Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: A Memorial Library of Countries and Communities - Poland Series: Lublin Volume", Jerusalem, 1957, p412.

- 1 2 Kuwalek, Robert (2003). The Ghetto in Lublin. "Voice of Lublin" Magazin no. 39

Further reading

- Kuwalek, Robert (2003). The Ghetto in Lublin. "Voice of Lublin" Magazin no. 39

- Zariz, Ruth (1994). Letters from haluzim in occupied Poland, 1940–1944. The Ghetto Fighters' House.

- Milgram, Avraham (2008) In my loneliness I hang all my hopes in you ..., 'Heritage Bag', No. 83.

- Blumenthal Nachman and Korzen Meyer [Eds.] (1957), Encyclopedia of Jewish Diaspora: A Memorial Library of Countries and Communities - Poland Series: Lublin Volume, Jerusalem.

- Adini, Jacob (1969). Bychawa - Memory Book, published by the Association of Bychawa people in Israel, Tel Aviv.

- Mandelsberg-Schildkraut, Bella (1965). On the History of Lublin Jewry, published by the Circle of Friends of the Late Bella Mandelsberg-Schildkraut, Tel-Aviv