Scallop aquaculture

Scallop aquaculture is the commercial activity of cultivating (farming) scallops until they reach a marketable size and can be sold as a consumer product. Wild juvenile scallops, or spat, were collected for growing in Japan as early as 1934.[1] The first attempts to fully cultivate scallops in farm environments were not recorded until the 1950s and 1960s.[2] Traditionally, fishing for wild scallops has been the preferred practice, since farming can be expensive. However worldwide declines in wild scallop populations have resulted in the growth of aquaculture. Globally the scallop aquaculture industry is now well established, with a reported annual production totalling over 1,200,000 metric tonnes [3] from about 12 species. China and Japan account for about 90% of the reported production.

Cultured species

There are varying degrees of aquaculture intensity used for different species of scallop. Therefore, cultured species can be divided into operations that are commercially well-established, those in the early commercial stages, those in development or experimental stages and those where potential for commercial farming has been expressed. Some species fall under multiple categories in different world regions.

Established commercial operations

- Aequipecten opercularis (United Kingdom, northern France and Spain, Norway)

- Argopecten irradians (China)

- Sub species A. irradians irradians (eastern USA)

- Sub species A. irradians concentricus (eastern USA)

- Argopecten purpuratus (Chile)

- Chlamys farreri (China)

- Chlamys islandica (eastern USA)

- Chlamys nobilis (Japan, China)

- Mizuhopecten/Patinopecten yessoensis (eastern RussiaJapan, China, Western Canada [hybridized with Patinopecten caurinus])

- Pecten fumatus (Australia)

- Pecten maximus (United Kingdom, northern France and Spain, Norway)

- Placopecten magellanicus (eastern USA)

Early commercial operations

- Argopecten ventricosus (Mexico)

- Chlamys islandica (Norway)

- Crassedoma giganteum (western North America)

Developmental or experimental

- Aequipecten tehuelchus (Argentina)

- Argopecten opercularis (Norway)

- Euvola ziczac (Venezuela)

- Nodipecten nodosus (Brazil, Venezuela)[4]

- Patinopecten caurinus (western North America)

- Pecten maximus (China)

Species with potential

- Amusium balloti (Australia)

- Chlamys varia (northern Europe)

- Chlamys islandica (northern Europe)

- Euvola vogdesi (Mexico)

- Euvola ziczac (Brazil)

- Flexopecten flexosus (northern Europe)

- Nodipecten subnodosus (Mexico)

Other species of note

Attempts at cultivation of Chlamys hastate and Chlamys rubida in western North America have been halted due to the small size and slow growth of both species.

Initial attempts made at cultivation of Pecten novazelandiae in New Zealand were hampered by large levels of fouling by mussels and by competition from a largely successful natural fishery.

Methods of culture

There are a variety of aquaculture methods that are currently utilized for scallops. The effectiveness of particular methods depends largely on the species of scallop being farmed and the local environment.

Spat collection

Collection of wild spat has historically been the most common way obtaining young scallops to seed aquaculture operations. There are a variety of ways in which spat can be collected. Most methods involve a series of mesh spat bags suspended in the water column on a line which is anchored to the seafloor. Spat bags are filled with a suitable cultch (usually filamentous fibers) onto which scallop larvae will settle. Here larvae will undergo metamorphosis into post-larvae (spat). Spat can then be collected and transferred to a farm site for on-growing.

Spat collectors will be set in areas of high scallop productivity where spat numbers are naturally high. However, to establish where the most appropriate areas to collect spat are, trial collectors will often be laid at a variety of different sites. Well-funded farms can potentially set thousands of individual spat bags in collection trials.

Hatcheries

Scallop hatcheries provide a number of advantages over traditional spat collection for supplying seed to aquaculture operations, most notably in selective breeding and genetic manipulation, as well as providing a regular supply of spat at a low price. While initial attempts to culture scallops in hatcheries were fraught with extremely low spawning and high larval mortality rates,[5] a number of successful techniques have now been developed.[6]

One of the most important aspects of hatchery rearing is obtaining and maintaining broodstock. Broodstock must be conditioned so to stimulate gonad development leading up to spawning and much research has been devoted to identifying the best diets and water quality requirements for broodstock.[6] Once broodstock have been conditioned, spawning can be induced. This is most commonly achieved by varying water temperature, increasing water circulation, or by an injection of serotonin (a neurotransmitter).[2] Following spawning, scallop eggs will develop into the “D” larval (shelled) stage in 2 to 4 days post-fertilization. As larvae, they continue to grow and can be fed a variety of microalgal diets with mixed algal diets being reported as giving higher growth rates than single species diets.[7] Settlement of larvae in hatcheries typically occurs between 35 and 45 days after fertilization of the scallop eggs when larvae are approximately 250 μm in size.[2] Following settlement, the larvae undergo metamorphosis where they rearrange their body form to begin their life as a seafloor dwelling juvenile scallop. Mortality rates are often highest during metamorphosis as larvae go through a series of behavioral and anatomical changes such as loss of the velum (the larval feeding structure) and development of new filter-feeding mechanisms and gills.[2] Post-settlement spat may be further grown in nursery tanks before being transferred to an on-growing system such as pearl nets.

Grow out stage

There are two recognized systems for the grow out stage of scallops. These are hanging culture and bottom culture. Each has its own benefits and drawbacks in terms of cost, ease of handling and quality of the finished product. Enclosed culture systems still have not yet been fully developed in a commercial context and development continues in this area. Such a system would have large advantages over other forms of culture as tight control of feed and water parameters could be maintained.

Hanging culture

Hanging culture relies on either a raft or longline system (with buoys and lines) that floats on the sea surface from which the cultured scallops are suspended, usually on ropes to which they are attached in some manner. Rafts are considerably more expensive than the equivalent distance of longline and are largely restricted to sheltered areas. However, raft systems require much less handling time. Longlines have proved effective for most farms to date and have the added advantage of being able to be completely submerged (with the exception of marker buoys) so to reduce visual pollution. From a raft or longline a variety of culture equipment can be supported. The main advantage of any form of hanging culture is in the exploitation of mid-water algal populations that cannot be fully utilized in other forms of culture.[8]

Pearl nets

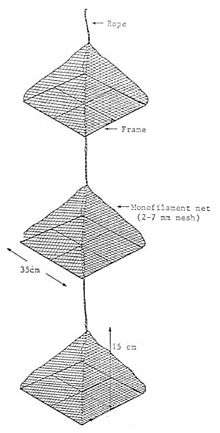

Once scallop spat have been collected, the most common way of growing them further is in pearl nets (small pyramid shaped nets usually about 350mm across with 2-7mm mesh). Here, they are usually grown to approximately 15mm in high stocking densities. Pearl nets are typically hung ten to a line and have the advantage of being light and collapsible for easy handling. Scallops are usually not grown to larger sizes in pearl nets due to the light construction of the equipment. Once juveniles have reached a desired size they can be transferred to another form of culture.[8]

Lantern nets

Lantern nets were first developed in Japan and are the most common method of growing out scallops following removal of juveniles from pearl nets. They allow the scallops to grow to adulthood for harvest due to their larger size and more sturdy construction. Lantern nets are employed in a similar fashion in the mid-water column and can be utilized in relatively high densities. Flow rate of water and algae is adequate and scallops will usually congregate around the edges of the circular net to maximise their food intake.[8]

Ear hanging

Ear hanging methods were developed to be a cheaper alternative to lantern nets. Subsequently, research has shown that growth of ear-hung scallops can also be higher than those in lantern nets. Ear hanging involves drilling a hole in the scallop ear (the protruding margin of shell near where the two shells join) and attaching it to a fixed submerged line for growth. Such a process can be relatively labor-intensive as each scallop must be individually handled and drilled (however, many operations now have machines for this process). Furthermore, high mortality rates can result from drilling if scallops are too small, are drilled incorrectly, or spend too much time out of water and become physiologically stressed. This has resulted in research being conducted into the optimal drilling size. This size has been shown to be species specific with small species not having good survival rates. As such, ear hanging is an effective method of growing out larger scallop species. If ear hanging is an appropriate method, scallops can be densely stocked in pairs on lines with as little as 100 mm between pairs. Scallops are maintained in this fashion until harvest. A variety of attachment products are constantly being tested with the best growth so far being obtained with a fastener called a securatie.[8]

Rope culture

Rope culture is very similar in principle to ear hanging with the only difference being the method of attachment. In rope culture, instead of scallops being attached by an ear hanging, they are cemented by their flat valve to a hanging rope. This method results in a similar growth and mortality rates as ear hanging but has the advantage of being able to set scallops from a small size. New cementing technologies are being continually developed with the aim of producing quicker setting adhesives to minimize the time scallops spend out of water so to minimize stress.[8]

Pocket nets

Pocket netting involves hanging scallops in individual net pockets. Pockets are most often set in groups hanging together. Pocket nets are not used extensively in larger farms due to their cost. However, handling time is low and so can be considered in smaller operations.[8]

Hog rigging

Hog rigging involves netting pockets of three or four scallops tied around a central line. This method is quick and cost effective and has been used to a great extent in the European Queen Scallop (Aequipecten opercularis) industry. However, its success in larger scallop species has been limited.[8]

Plastic trays

Growing scallops in suspended plastic trays such as oyster cages can serve as an alternative to equipment like lantern nets. However, such systems can be expensive and have a rigid structure so cannot be folded and easily stored when not in use. In general, plastic trays are mostly used for temporary storage of scallops and for transportation of spat.[8]

Bottom culture

Methods of bottom culture can be used in conjunction with or as an alternative to hanging culture. The main advantage of using methods of bottom culture is in the lower cost of reduced buoyancy needs as equipment is supported by the seabed. However, growing times have been noted as being longer in some cases due to the loss of use of mid-water plankton.[8]

Plastic bottom trays

Plastic trays such as oyster cages can again be utilized in bottom culture techniques. They provide simple and easy to use system. Plastic trays are effective in large numbers but their size is limited by the growth rates of scallops near the centre of cages due to reduced water and food flow rates.[8]

Wild ranching

Wild ranching is by far the cheapest of all forms of scallop farming and can be very effective when large areas of seabed can be utilized. However, there can often be problems with predators such as crabs and starfish so areas must be cleared and then fenced to some degree. However, clearing and fencing will not prevent settlement of larvae of predators. Harvesting is usually done by dredge further reducing costs. On smaller farms, however, divers may be employed to harvest.[8]

Feeding

Scallops are filter feeders that are capable of ingesting living and inert particles suspended in the water column.[9] In culture, scallop diets contain primarily phytoplankton that occur either naturally at a site or are produced artificially in culture. Much research has been conducted into what species of phytoplankton are most effective for inducing growth (and particularly growth of the adductor muscle). Such research has shown that of the species commonly used in bivalve aquaculture, Isochrysis aff. galbana (clone T-Iso) and Chaetoceros neogracile are the most effective.[10] Recently, with the increase of enclosed farming techniques, a large amount of work has been directed at development of an artificial microalgal substitute that is more cost effective than traditional feeds.[11]

Microalgae cultures may also be manipulated in order to produce algae with a more desirable protein, lipid and carbohydrate profile and much work is being conducted in this area. Furthermore, microalgal species used in scallop culture usually have high levels of vitamins such as vitamin C.[2] The dietary requirements of scallops differ depending on species and life stage. For example, increased protein content of the microalgal diet of broodstock has been shown to reduce time to spawning maturity and increase fecundity.[12] Similar positive results for growth and survival have been observed in larvae fed with high protein diets.[13] However, speculation remains that lipids are also very important to scallop larvae.[2]

Diseases, parasites and phycotoxins

Diseases

As with any aquaculture species, the incidence of diseases (and parasites) can be amplified by the close proximity of individuals. The occurrence of diseases in scallop culture has been presented as subdued[2] and not well understood;[14] however, the Chinese production of Farrer's scallop (Chlamys farreri) was devastated by malacoherpesviridae in the 1990s.[15][16] Databases are being assembled and industry and research institutions are cooperating for an improved effort against future outbreaks.

Parasites

A similar situation is seen with parasites as is seen with diseases: at this stage little is known about scallop parasites and few have been identified. As of 2006, no mass deaths caused by parasites have been reported.[2] There are only 17 parasites and commensals that have been described as being associated with scallops (for a full list see Shumway & Parsons [2006], pp. 1187–1188).

Phycotoxins

The occurrence of phycotoxins is generally associated with specific bodies of water and must be considered during establishment of farms as many phycotoxins derived from toxic algae can have detrimental effects on consumers of infected meat.[17] With respect to scallop culture, two categories of toxins have been reported: Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) and amnesic shellfish poisoning (ASP). PSP has been reported for a number of years in Placopecten magellanicus in the Northwest Atlantic and so must be considered in culture operations, particularly as P. magellanicus is reported as being a slow detoxifyer of the toxin.[2] ASP is a neurotoxin produced by some marine diatoms and has also been reported in scallops from the Northwest Atlantic (Bird & Wright, 1989). Diarrehetic shellfish poisons (DSP) have also been identified as a potential problem, however, they have not yet been reported in scallop culture. DSPs cause gastrointestinal distress in humans and are produced by dinoflagellates that may be ingested by scallops.[18]

End product

Once scallops have been grown, harvested and processed the principal end product is the meat, which usually consists of just the adductor muscle (fresh or frozen). However, it is becoming increasingly popular to sell the muscle with the roe still attached and also to sell whole animals (primarily in North America). Thus, the industry now produces three distinguishably different products.

While the shelf life of a live scallop is limited, the marketing of this product allows scallop farmers to sell smaller animals and so increase cash flow. Top quality scallop muscle can demand a high market price, which fluctuates with production, success of wild scallop fisheries and a number of other global factors.[2]

Environmental impacts

Contrary to common perception concerning the negative impacts of many aquaculture practices (particularly finfishes[19]), scallop aquaculture (and indeed other shellfish aquaculture practices) in many parts of the world are considered to be a sustainable practice that can have positive ecosystem effects. This is a result of filter-feeding bivalves removing suspended solids, unwanted nutrients, silt, bacteria and viruses from the water column so to increase water clarity which, in turn, improves pelagic and benthic ecosystems, particularly by promoting growth of vegetation such as seagrasses.[20]

With this considered, such positive impacts are very area specific and one of the main negative environmental impacts scallop culture can create in some other areas is the eutrophication of waters. This has been well observed in Russia where culture of scallops in partially closed bays has resulted in eutrophication and so changes in species composition and structural and functional parameters of pelagic and benthic communities.[2] Monitoring has shown that after farms are disbanded, ecosystems were restored within 5–10 years. This is in line with a large body of data showing bivalve aquaculture activities result in various environmental changes including changes in hydrological regime, ecological communities (including planktonic communities), biochemical composition of waters, biodeposits and invertebrate settlement success.[2] Furthermore, aquaculture farms are a source of visual pollution and so often attract public opposition in highly populated coastal areas.

References

- ↑ Kinoshita T (1935) A test for natural spat collection of the Japanese scallop. Report of the Hokkaido Fish Research Station, 273:1-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Shumway SE & Parsons GJ (2006). Scallops: Biology, Ecology and Aquaculture. Elsevier B.V., Amsterdam.

- ↑

- ↑ Cervigon, Fernando (Editor), 1983: La acuicultura en Venezuela. Caracas. 123p

- ↑ Dabinett PE (1989). Hatchery production and grow-out of the giant scallop Placopecten magellanicus. Bulletin of the Aquaculture Association of Canada, 89(3):68-70.

- 1 2 Neima PG (1997). Report on commercial scallop hatchery design. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, No. 2176. 55 pp.

- ↑ Ryan CM (2000). Effect of algal cell density, dietary composition, growth stage and macronutrient concentration on growth and survival of giant scallop Placopecten magellanicus (Gmelin, 1791) larvae and spat in a commercial hatchery. MSc Thesis. Memorial University, Newfoundland.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Hardy D (1991). Scallop Farming. (ed. D Hardy) Fishing News Books, Blackwell Science, Oxford.

- ↑ Lucas A (1982). La nutrition des larves de bivalves. Oceanis 8(5):363-388.

- ↑ Coutteau P & Sorgeloos P (1992). The use of algal substitutes and the requirement for live algae in the hatchery and nursery rearing of bivalve molluscs: an international survey. Journal of Shellfish Research, 11:467-476

- ↑ Robert R & Trintigna P (1997). Substitutes for live microalgae in mariculture: a review. Aquatic Living Resources, 10:315-327.

- ↑ Farías A & Uriarte I (2001). Effect of microalgae protein on the gonad development and physiological parameters of Chilean scallop Argopecten purpuratus (Lamark, 1819). Journal of Shellfish Research, 20:97-105.

- ↑ Uriarte I (2000). Informe de Avance No.3, FONDECYT 1970807, Chile. 11p.

- ↑ Ball MC & McGladdery SE (2001). Scallop parasites, pests and diseases: implications for aquaculture development in Canada. Bulletin of the Aquaculture Association of Canada, 101(3):13-18.

- ↑ "An Overview of China's Aquaculture", p. 6. Netherlands Business Support Office (Dalian), 2010. Accessed 13 Aug 2014.

- ↑ Ren W, Chen H, Renault T, Cai Y, Bai C, Wang C, Huang J (2013) Complete genome sequence of acute viral necrosis virus associated with massive mortality outbreaks in the Chinese scallop, Chlamys farreri" Virol J 10(1) 110

- ↑ Shumway SE, Sherman-Caswell S & Hurst WJ (1988). Paralytic shellfish poisoning in Maine: monitoring a monster. Journal of Shellfish Research, 7:643-652.

- ↑ Yautomo T, Murata M, Oshima Y, Matsumoto GK & Clardy J (1984). Diarrehetic shellfish poisoning. In: Seafood Toxins (ed. EP Ragelis). American Chemical Society, Washington D.C. pp. 207-214.

- ↑ Tovar A, Moreno C, Mánuel-Vez MP & García-Vargas M (2000). Environmental impacts of intensive aquaculture in marine waters. Water Research, 34(1):334-342.

- ↑ Shumway SE, Davis C, Downey R, Karney R, Kraeuter J, Parsons J, Rheault R & Wikfors G (2003). Shellfish aquaculture — In praise of sustainable economies and environments. World Aquaculture, 34(4):15-17