Rouché's theorem

Rouché's theorem, named after Eugène Rouché, states that if the complex-valued functions f and g are holomorphic inside and on some closed contour K, with |g(z)| < |f(z)| on K, then f and f + g have the same number of zeros inside K, where each zero is counted as many times as its multiplicity. This theorem assumes that the contour K is simple, that is, without self-intersections. Rouché's theorem is an easy consequence of a stronger symmetric Rouché's theorem described below.

Symmetric version

Theodor Estermann (1902–1991) proved in his book Complex Numbers and Functions the following statement: Let be a bounded region with continuous boundary . Two holomorphic functions have the same number of roots (counting multiplicity) in , if the strict inequality

holds on the boundary .

The original Rouché's theorem then follows by setting and .

Usage

The theorem is usually used to simplify the problem of locating zeros, as follows. Given an analytic function, we write it as the sum of two parts, one of which is simpler and grows faster than (thus dominates) the other part. We can then locate the zeros by looking at only the dominating part. For example, the polynomial has exactly 5 zeros in the disk since for every , and , the dominating part, has five zeros in the disk.

Geometric explanation

It is possible to provide an informal explanation of Rouché's theorem.

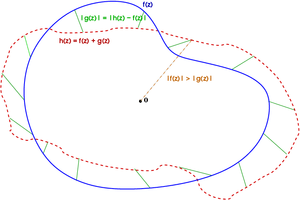

Let C be a closed, simple curve (i.e., not self-intersecting). Let h(z) = f(z) + g(z). If f and g are both holomorphic on the interior of C, then h must also be holomorphic on the interior of C. Then, with the conditions imposed above, the Rouche's theorem in its original (and not symmetric) form says that

- If |f(z)| > |h(z) − f(z)|, for every z in C, then f and h have the same number of zeros in the interior of C.

Notice that the condition |f(z)| > |h(z) − f(z)| means that for any z, the distance from f(z) to the origin is larger than the length of h(z) − f(z), which in the following picture means that for each point on the blue curve, the segment joining it to the origin is larger than the green segment associated with it. Informally we can say that the blue curve f(z) is always closer to the red curve h(z) than it is to the origin.

The previous paragraph shows that h(z) must wind around the origin exactly as many times as f(z). The index of both curves around zero is therefore the same, so by the argument principle, f(z) and h(z) must have the same number of zeros inside C.

One popular, informal way to summarize this argument is as follows: If, say, Gérard de Nerval were to walk his lobster on a leash around and around a tree, such that the leash's length was always less than Nerval's distance to the tree, then the lobster would wind around the tree exactly as many times as Nerval.

Applications

Consider the polynomial (where ). By the quadratic formula it has two zeros at . Rouché's theorem can be used to obtain more precise positions of them. Since

- for every ,

Rouché's theorem says that the polynomial has exactly one zero inside the disk . Since is clearly outside the disk, we conclude that the zero is . This sort of arguments can be useful in locating residues when one applies Cauchy's residue theorem.

Rouché's theorem can also be used to give a short proof of the fundamental theorem of algebra. Let

and choose so large that:

Since has zeros inside the disk (because ), it follows from Rouché's theorem that also has the same number of zeros inside the disk.

One advantage of this proof over the others is that it shows not only that a polynomial must have a zero but the number of its zeros is equal to its degree (counting, as usual, multiplicity).

Another use of Rouché's theorem is to prove the open mapping theorem for analytic functions. We refer to the article for the proof.

Proof of the symmetric form of Rouché's theorem

Let be a simple closed curve whose image is the boundary . The hypothesis implies that f has no roots on , hence by the argument principle, the number Nf(K) of zeros of f in K is

i.e., the winding number of the closed curve around the origin; similarly for g. The hypothesis ensures that g(z) is not a negative real multiple of f(z) for any z = C(x), thus 0 does not lie on the line segment joining f(C(x)) to g(C(x)), and

is a homotopy between the curves and avoiding the origin. The winding number is homotopy-invariant: the function

is continuous and integer-valued, hence constant. This shows

See also

- Fundamental theorem of algebra, for its shortest demonstration yet, while using Rouché's theorem

- Hurwitz's theorem (complex analysis)

- Rational root theorem

- Properties of polynomial roots

- Riemann mapping theorem

- Sturm's theorem

Notes

References

- Beardon, Alan (1979). Complex Analysis: the Winding Number principle in analysis and topology. John Wiley and Sons. p. 131. ISBN 0-471-99672-6.

- Titchmarsh, E. C. (1939). The Theory of Functions (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 117–119, 198–203. ISBN 0-19-853349-7.