Robert of Shrewsbury (died 1168)

| Robert of Shrewsbury | |

|---|---|

| Abbot of Shrewsbury | |

Interior of Shrewsbury Abbey | |

| Church | Catholic |

| Archdiocese | Province of Canterbury |

| Appointed | 1148 |

| Term ended | 1168 |

| Predecessor | Ranulf |

| Successor | Adam |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Possibly Downing, Flintshire |

| Died |

1168 Shrewsbury |

| Previous post | Prior of Shrewsbury |

Robert of Shrewsbury (died 1168) or Robertus Salopiensis was a Benedictine monk, prior and later abbot of Shrewsbury Abbey, and a noted hagiographer.[1]

Identity and origins

Robert was a common name in the 12th century among the Anglo-Norman ruling class, so there must have been numerous Roberts of Shrewsbury. Robert the monk is to be distinguished especially from the Robert of Shrewsbury, a secular cleric, who became Bishop of Bangor towards the end of the century. The monk Robert is thought to have been a member of the Pennant family of Downing, a few miles north-west of Holywell, the fountain of Saint Winifred.[2] If so, it is unlikely he was born in Shrewsbury: the toponymic cognomen probably just refers to his long-term connection with the abbey. He appears first as prior of the abbey in 1137, suggesting a birth date around the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries.

Prior

As prior of Shrewsbury Abbey, Robert is generally credited with greatly promoting the cult of St Winifred by translating her relics from Gwytherin to Shrewsbury Abbey and writing the most influential life of the saint.[5] Robert's own account of the translation is attached to the life.[6] It relates that the monks of Shrewsbury Abbey, after its foundation by Roger of Montgomery, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, lamented their house's lack of relics.[7] They had heard that the bodies of many saints lay in Wales. During the reign of Henry I one of the brothers fell prey to a mental illness and the sub-prior Ralph had a dream in which a beautiful virgin told him the sick man would recover if they went to celebrate Mass at the fountain of St Winifred. Ralph kept quiet about the vision, fearing derision, until the monk had been ill for forty days. As soon as he revealed it, the brothers sent two of their number who were ordained priests to celebrate Mass at Holywell. The sick man immediately began to recover and achieved full health after he too had visited the shrine and bathed in the pool.

According to Robert's account, he and Richard, another monk, were sent on a mission by Abbot Herebert (also rendered simply as Herbert)[8] to negotiate the translation of St Winifred's relics, taking advantage of a temporary improvement in political conditions in 1137, during the Anarchy that followed the seizure of power by Stephen.[9] After approaching the Bishop of Bangor, then David the Scot,[10] and the local prince, either Gruffudd ap Cynan or Owain Gwynedd,[11] they organised a party of seven, which included the prior of Chester, to collect the body of the saint. Initially the local people were strongly opposed to the removal, but a convenient vision persuaded the parish priest to assemble them.

- Prior Robert, seeing such a numerous assembly, spoke unto them by an interpreter, in this manner: "I, and my companions are come hither by divine appointment, to obtain of you St. Wenefride's body, that it may be honoured in our city and monastery, both which are much devoted unto her. The virgin herself, (as your pastor here present knows,) hath by visions manifested her will; and she cannot but be displeased with those who are so bold as to contradict what she desires to be done."[12]

This reduced opposition to one man, who was bribed, clearing the way for translation.[13] Miraculously, claims Robert, he was able to identify the grave of Winifred without aid, although he had never been there before.[14] The body was disinterred and carried to Shrewsbury, a journey of seven days. There it was laid in the church of St Giles to await the permission and presence of the Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield. After further miracles, it was at last taken in procession into the town. The expectation of an episcopal blessing ensured it was witnessed by "an incredible concourse of devout people"[15] as it was taken to be placed on the altar of the Abbey church, where further miracles were reported.

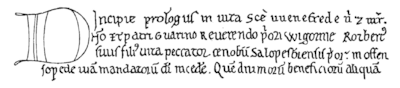

Robert's life of St Winifred and account of her translation are thought to date from 1139,[1] just over a year after his mission into Wales. There had been an earlier life, attributed incorrectly to St Elerius,[16] but probably written about 1100 and the manuscript is held with one copy of Robert's among the Cotton manuscripts.[1] A manuscript copy of Robert's life is also among the Laud Manuscripts. Robert addressed his account to Warin, the prior of the Benedictine cathedral chapter, who is mentioned in that post from 1133 to 1140.[17] Robert calls Warin his "master and father," suggesting that he had studied under Warin during his own education or monastic formation.

Abbot

Herebert, the abbot who had sent Robert into Wales, was deposed by a Legatine council at Westminster in 1138, but the reasons are not known: irregularities in his election have been suspected, although he had been consecrated in his position by William de Corbeil, the Archbishop of Canterbury.[18][19] He was succeeded by Ranulf, whose name occurs as late as 1147.[20] Robert of Shrewsbury probably became the fifth abbot of the house in 1148.[1]

Little of known of his incumbency, apart from his success in recovering two portions of the tithes of Emstrey parish church which had been granted "against conscience and the consent of his convent" by Ranulf to the church at Atcham. Emstrey was a large parish, important to the Abbey: it stretched from the western bank of the River Severn opposite Atcham to the Abbey Foregate.[21] The Abbey cartulary contains an instrument by which the Archbishop, Theobald of Bec, orders Bishop Walter to restore the situation.[22] Underlying the issue was political and economic competition between Shrewsbury Abbey and its great Augustinian rivals. Lilleshall Abbey was attempting to tighten its grip on Atcham parish. It had recently acquired the advowson and was later allowed to appropriate the church by Thomas Becket.[23]

Death

Robert's year of death is sometimes given as 1167.[22] However, 1168 is now generally accepted by historians.[1][8] This date is given in the Annals of Tewkesbury Abbey, which pairs his death with that of Robert de Beaumont, 2nd Earl of Leicester.[24] It seems likely he died and was buried at Shrewsbury Abbey.

Reception and influence

Robert is generally accepted as strengthening the cult of Winifred, who had hitherto been an obscure Welsh saint, so that she became the focus of pilgrimages from Shrewsbury and other centres from the 14th century to the present.[1] Prior Robert's mission to Wales was outlined during the 14th century in the sermon for St Winifred's day by the Shropshire Augustinian John Mirk, part of his much-copied and printed Festial.[25] The shrine at Holywell was rebuilt by Margaret Beaufort, Henry VII's mother, in 1485 and was a centre of recusancy after the English Reformation. Also in 1485, Robert's life of Winifred was translated into English for printing by William Caxton. It was translated again by the Jesuit John Falconer in 1635 under the title The Admirable Life of Saint Wenefride.[1] This was the basis of Philip Leigh's Life and Miracles of S. Wenefride; Virgin, Martyr and Abbess; Patroness of Wales, published in 1712[26] and still widely available – usually in a 19th-century edition signed by an anonymous editor Soli Deo Gloria.[27] The Bollandists published the lives by Pseudo-Elerius and Robert in Latin together in 1887.[28] A more recent edition of the life was published in 1976.

In fiction

Robert of Shrewsbury is featured in The Cadfael Chronicles, by the Shropshire novelist Edith Pargeter, writing as Ellis Peters. In these tales he is the main antagonist of the eponymous hero within the Abbey: officious and ambitious, he feels existentially threatened by Cadfael, whose "gnarled, guileless-eyed self-sufficiency caused him discomfort without a word amiss or a glance out of place, as though his dignity were somehow under siege."[29] The first of the series, A Morbid Taste for Bones, reworks Robert's own account of the translation of St Winifred into a murder mystery. The Carlton Television adaptation, in which Prior Robert is played by Michael Culver, dislocates the chronology, placing at the beginning One Corpse Too Many. This deals with the siege and taking of Shrewsbury by the king’s forces, which actually took place a year after the translation. Pargeter uses the known facts of Robert's life to imaginative effect. In Monk's Hood he waits expectantly for appointment as abbot while Heribert is away at the legatine council, only to be frustrated by the appointment of the council's nominee, named in the novel Radulfus[30] – an incident which is followed by the use of his surname, Pennant, when he is introduced to the new abbot.[31]

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Farmer, D. H. "Shrewsbury, Robert of". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23728. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, p. 41-2.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, p.34

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, p.74

- ↑ Poncelet, p. 1275-6.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, p. 36.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, p. 37.

- 1 2 M J Angold, G C Baugh, Marjorie M Chibnall, D C Cox, D T W Price, Margaret Tomlinson and B S Trinder. Houses of Benedictine monks: Abbey of Shrewsbury – Abbots of Shrewsbury, in Gaydon and Pugh, pp. 30-37.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, p. 38.

- ↑ Smedt et al, p. 728, annotatum c.

- ↑ Smedt et al, p. 728, annotatum g.

- ↑ Leigh (1817 ed.), p. 80-1.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, p. 39.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, p. 40.

- ↑ Leigh (1817 ed.), p. 84.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, p. 33-4.

- ↑ Greenway. Priors of Worcester.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, p. 107-8.

- ↑ M J Angold, G C Baugh, Marjorie M Chibnall, D C Cox, D T W Price, Margaret Tomlinson and B S Trinder. Houses of Benedictine monks: Abbey of Shrewsbury, in Gaydon and Pugh, pp. 30-37.

- ↑ M J Angold, G C Baugh, Marjorie M Chibnall, D C Cox, D T W Price, Margaret Tomlinson and B S Trinder. Houses of Benedictine monks: Abbey of Shrewsbury, in Gaydon and Pugh, pp. 30-37.

- ↑ Eyton, Volume 6, p. 170-1.

- 1 2 Owen and Blakeway, p. 108.

- ↑ Eyton, Volume 8, p. 245.

- ↑ Luard (ed), p. 50.

- ↑ Mirk, p. 179-80.

- ↑ Leigh, 1712 edition.

- ↑ Leigh, 1817 edition.

- ↑ Smedt, Charles De; Hoof, Willem van; Backer, Joseph de, eds. (1887). Acta Santorum. 62. Paris: Victor Palmé. p. 691-759. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ↑ Peters, p. 27.

- ↑ Peters, p. 537.

- ↑ Peters, p. 538.

References

- Eyton, Robert William (1858). Antiquities of Shropshire. 6. London: John Russell Smith. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Eyton, Robert William (1858). Antiquities of Shropshire. 8. London: John Russell Smith. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Farmer, D. H. "Shrewsbury, Robert of". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23728. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Gaydon, A. T.; Pugh, R. B., eds. (1973). A History of the County of Shropshire. 2. London: British History Online. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- Greenway, Diana E., ed. (1971). Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066-1300: Volume 2, Monastic Cathedrals (Northern and Southern Provinces). Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Leigh, Philip (1712). Life and Miracles of S. Wenefride; Virgin, Martyr and Abbess; Patroness of Wales. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- Leigh, Philip (1817). Soli Deo Gloria, ed. Life and Miracles of S. Wenefride; Virgin, Martyr and Abbess; Patroness of Wales. London: Thomas Richardson. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- Luard, Henry Richards, ed. (1864). Annales Monastici. 1. London: Longman, Green. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- Mirk, John (1905). Erbe, Theodore, ed. Mirk's Festial: a Collection of Homilies. London: Kegan Paul et al., for the Early English Text Society. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Owen, Hugh; Blakeway, John Brickdale (1825). A History of Shrewsbury. 2. London: Harding Leppard. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- Peters, Ellis (1992). The First Cadfael Omnibus (1994 ed.). London: Harding Leppard. ISBN 9780751504767.

- Poncelet, Albertus, ed. (1901). Bibliotheca Hagiographica Latina Antiquæ et Mediæ Ætatis. 2. Brussels: Socii Bollandiani. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- Smedt, Charles De; Hoof, Willem van; Backer, Joseph de, eds. (1887). Acta Santorum. 62. Paris: Victor Palmé. p. 691-759. Retrieved 1 March 2016.