Richard de Southchurch

Sir Richard de Southchurch (Suthchirche, Suthcherch) (died 1294) was a knight and part of the landowning aristocracy of Essex in the thirteenth century. He was High Sheriff of Essex and of Hertfordshire in the years 1265–67, and as such became involved in the Second Barons' War (1264–1267). Southchurch has earned a special place in the historiography of the period due to an episode during the war where he allegedly planned to attack London with incendiary cocks.

Biography

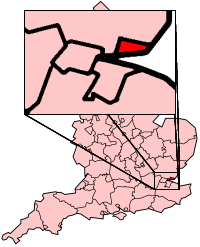

Little is known of Southchurch's background, but his family came from the manor of Southchurch, now part of Southend-on-Sea. Richard de Southchurch held this manor of the Prior and Convent of Christ's Church, Canterbury.[1] He also held other land in the county of Essex, including Prittlewell, which he held in fee of the king.[2] He served as sheriff of the combined shrievalties of Essex and Hertfordshire from 27 October 1265 to 12 June 1267.[3] In 1279, he received a pardon and was acquitted of a fine of 100 shilling for being present at the theft of a hart at the king's forest of Chelmsford.[4] In 1289 he was also acquitted of the great sum of 1000 pounds for perjury, in return for releasing the manor of Hatfield Peverel to the king.[5] Southchurch was dead by 2 April 1294, when the escheator was ordered to deliver his lands to his son and heir, Peter de Southchurch.[2][6]

Involvement in Barons’ War

In the mid-1260s, England found herself in a state of civil war between king Henry III and members of his aristocracy, a conflict known as the Second Barons' War. In April 1267, Gilbert de Clare entered London with the baronial forces. The city welcomed him, and king Henry III had to set up camp at Stratford, besieging the capital. Orders were sent out to the sheriffs of Kent and Essex to procure supplies for the royal army.[7] It was in this situation that Southchurch, in his capacity as sheriff, levied requisitions on Chafford Hundred of;

...oats and wheat, of bacon, beef, cheese and pease, 'pur sustenir le ost au Rey'; of chickens to feed the wounded and tow and eggs to make dressings for their wounds and linen for bandages, of chord to make ropes for the catapults, of picks and calthrops and spades to lay low the walls of London, and finally of cocks, forty and more, to whose feet he declared he would tie fire, and send them flying into London to burn it down.[8]

The story survives through the Hundred Rolls, the great survey of the English hundreds made by Edward I, in 1274-5, on returning to his new kingdom from crusade. The scheme, impractical as it might seem, was supposedly based on contemporary sagas of Viking heroes. But the complaints of the local community were based on the fact that Southchurch had taken all the supplies home to his own manor of Southchurch, received 200 marks from the exchequer, yet never paid out any of what the owners of the goods were entitled to.[9]

Historical transmission

The account of Southchurch's provisioning was first made available to a wider audience through the writings of the English historian Helen Cam. Cam was responsible for groundbreaking work on the Hundred Rolls, and their relevance to English local government, through her Studies in the Hundred Rolls (1921) and The Hundred and the Hundred Rolls (1930).[10] In both of these she made mention of what she calls '...the most picturesque series of extortions recorded in the Essex returns.' It was, however, in a paper published in the English Historical Review as early as 1916 that she gave the most detailed account of Southchurch's plot. Here she traced the dissemination of the Viking legend through Geoffrey of Monmouth, and speculated that Southchurch could have been acquainted with a later version by Gaimar, Wace or Layamon, or through a local, popular legend.[11]

The story was later retold by Sir Maurice Powicke in his King Henry III and the Lord Edward (1947).[12] Yet even though both Cam and Powicke had included the tale as a humorous anecdote, it was not until Michael Prestwich wrote his monograph of Edward I in 1988 that anyone considered the possibility that the story of the incendiary roosters was simply a 'confidence trick' on Southchurch's part.[13] Powicke, in Prestwich's words; 'is to be counted among those who fell for the sheriff’s ruse.'[14]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Morant, Philip (1816). The History and Antiquities of the County of Essex. Chelmsford.

- 1 2 Public Record Office (1912). Inquisitions Post Mortem, vol. III, Edward I. London. pp. 109–10.

- ↑ PRO (1963). List of Sheriffs for England and Wales, From the Earliest Times to A.D. 1831. New York (reprint).

- ↑ PRO (1900). Calendar of Close Rolls, vol. I, Edward I (1272-9). London. p. 526.

- ↑ PRO (1905). Calendar of Close Rolls, vol. III, Edward I (1288-96). London. pp. 10, 237.

- ↑ PRO (1911). Calendar of Fine Rolls, vol. I, Edward I (1272-1307). London. p. 336.

- ↑ Cam (1930), p. 101; Powicke, p. 543.

- ↑ Cam, (1921), p. 175. In the original Latin: "XL gallos ad portendum ingnem ad incendendum civitatem Londomarium", Cam (1916), p. 98.

- ↑ Cam, (1930), p. 102.

- ↑ Cam, (1921; 1930).

- ↑ Cam, (1916). Cam here also points out that, while the original legends featured sparrows, cocks would probably lack the homing instinct necessary for the plan to work.

- ↑ Powicke, p. 544.

- ↑ Prestwich, p. 58.

- ↑ Prestwich, p. 59; see also ibid., p. 95.

References

- Prestwich, M. (1988). Edward I. London: Methuen. pp. 58–9, 95. ISBN 0-413-28150-7.

- Cam, H. M. (1916). "The Legend of the Incendiary Birds". English Historical Review. XXXI: 98–101. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXXI.CXXI.98.

- Cam, H. M. (1921). Studies in the Hundred Rolls: Some Aspects of Thirteenth-Century Administration. Oxford. pp. 175–6.

- Cam, H. M. (1930). The Hundred and the Hundred Rolls: An Outline of Local Government in Medieval England. Methuen. pp. 101–2.

- Powicke, F. M. (1947). King Henry III and the Lord Edward: The Community of the Realm in the Thirteenth Century. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 544.