St Mary's Church, Reculver

St Mary's Church, Reculver, was founded in the 7th century as either a minster or a monastery on the site of a Roman fort at Reculver, which was then at the north-eastern extremity of Kent in south-eastern England. In 669, the site of the fort was given for this purpose by King Ecgberht of Kent to a priest named Bassa, beginning a connection with Kentish kings that led to King Eadberht II of Kent being buried there in the 760s, and the church becoming very wealthy by the beginning of the 9th century. From the early 9th century to the 10th the church was treated as essentially a piece of property, with ownership passing between kings of Mercia and Wessex and the archbishops of Canterbury. Viking attacks may have extinguished the church's religious community in the 9th century, although an early 11th-century record indicates that the church was then in the hands of a dean accompanied by monks. By the time of Domesday Book, completed in 1086, St Mary's was serving as a parish church.

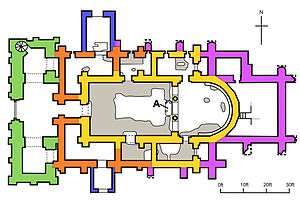

The original building, which incorporated stone and tiles scavenged from the Roman fort, was a simple one consisting only of a nave and an apsidal chancel, with a small room, or porticus, built out from each of the church's northern and southern sides where the nave and chancel met. The church was much altered and expanded during the Middle Ages; the last addition, in the 15th century, was of north and south porches leading into the nave. This expansion coincided with a long period of prosperity for the settlement of Reculver, but its decline led to the church's decay and, in the face of coastal erosion, its almost complete demolition in 1809.

The church's twin towers were preserved by the intervention of Trinity House, since they had long been important as a landmark for shipping. Some materials from the structure were incorporated into a replacement church, also dedicated to St Mary, built at Hillborough in the same parish. Much of the rest was used for the building of a new harbour wall at Margate, known as Margate Pier. Other remnants of the original 7th-century church apart from those on the site include fragments of a high cross of stone that stood inside the church, and two stone columns that formed part of an arch between the nave and chancel, which were still in place when the church was demolished. These are now kept in Canterbury Cathedral, and are among the features that have led to the church being described as an exemplar of Anglo-Saxon church architecture and sculpture.

Origins

.jpg)

The first church known to have existed at Reculver was founded in 669, when King Ecgberht of Kent gave land there to Bassa the priest for this purpose.[2][Fn 1] The author of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle "clearly considered this to be a significant event",[7] and it may be that King Ecgberht's intention in founding a church at Reculver was to create an ecclesiastical centre with a strong English element, to counterbalance domination of the Canterbury church by Archbishop Theodore, from Tarsus, now in Turkey, Abbot Hadrian of St Augustine's, from North Africa, probably Cyrenaica, and their equally "non-native followers."[8][Fn 2] Historians vary over whether to call the church a minster or a monastery – thus Susan Kelly uses the former term, but Nicholas Brooks uses the latter, commenting that:[12]

[w]e do not know whether the Kentish monasteries had been founded as communities of monks and nuns dedicated to the service of God [and living in monasteries and nunneries], or whether the male communities were from the start bodies of secular clergy [operating from minsters] who, like the archiepiscopal familia at Canterbury, accepted a degree of communal (or monastic) discipline and who were responsible for the pastoral care of extensive rural areas. ... [T]he distinction between the regular and secular clergy was blurred from the very beginning in England. Indeed the word monasterium does not necessarily refer to a house of monks in the eighth and ninth centuries, but like its English equivalent, minster ..., was also the normal term for a church served by a body of clergy. ... By the ninth century the communities of the Kentish monasteries were certainly composed of priests, deacons, and clergy in lesser orders, just like the cathedral community at the 'head minster', [Canterbury Cathedral].— Nicholas Brooks, The Early History of the Church of Canterbury, 1984[13]

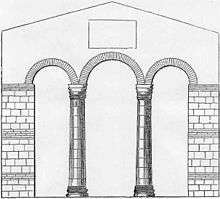

The foundation of this church, sited within the remains of the Roman fort of Regulbium, exemplifies the "widespread practice [in Anglo-Saxon England] of re-using Roman walled places for major churches";[14] the new church was built "almost completely from demolished Roman structures".[15] The building formed a nave measuring 37.5 feet (11.4 m) by 24 feet (7.3 m) and an apsidal chancel, which was externally polygonal but internally round, and was entered from the nave through a triple arch formed by two columns made of limestone from Marquise, in the Pas-de-Calais region of northern France.[16] The arches were formed using Roman tiles, but the columns were made for the church rather than being Roman in origin.[17][Fn 3] Around the inside of the apse was a stone bench, and two small rooms, or porticus, forming rudimentary transepts were built out from the north and south sides of the church where the nave met the chancel, from which they could be accessed.[19][Fn 4] The presence of a stone bench around the inside of the apse has been attributed to influence from the Syrian Church, at a time when its followers were being displaced.[21] The walls of the church were rendered inside and out, giving them a plain appearance and hiding the masonry.[22]

Ten years after the foundation of the church, in 679, King Hlothhere of Kent granted lands at Sturry, about 6.2 miles (10 km) south-west of Reculver, and at Sarre, in the western part of the Isle of Thanet, across the Wantsum Channel to the east, to Abbot Berhtwald and his "monastery".[23][Fn 5] The grant was made at Reculver, and the charter in which it was recorded was probably written by a Reculver scribe. The grant of Sarre in particular is significant:

Sarre was a highly strategic place, overlooking the confluence of the Wantsum and the Great Stour, [and] directly linked to Canterbury ... In the early 760s it was the site of a toll-station, where the agents of the Kentish kings collected dues on trading ships using the Wantsum route ... The grant of Sarre to Reculver must be regarded as a sign of enormous royal favour to the [church there] ... and it may be that the [church at Reculver] received a share of the royal tolls levied at Sarre.— Susan Kelly, "Reculver Minster and its early charters", 2008[25]

In the original, 7th-century charter recording this grant, Reculver is referred to as a civitas, or city, but this is probably a reference to either its Roman past or the church's monastic status, rather than a large population centre.[26] In 692 Reculver's abbot Berhtwald was elected Archbishop of Canterbury, from which position he probably offered Reculver patronage and support.[27] Bede, writing no more than 40 years later, described Berhtwald as having been well educated in the Bible and experienced in ecclesiastical and monastic affairs,[28] but in terms indicating that Berhtwald was not a scholar.[29][Fn 6]

Further charters show that the monastery at Reculver continued to benefit from Kentish kings in the 8th century, under abbots Heahberht (fl. 748x762), Deneheah (fl. 760) and Hwitred (fl. 784), acquiring lands in Higham and Sheldwich and exemption from the toll due on one ship at Fordwich,[31] and King Eadberht II of Kent was buried in the church in the 760s.[32][Fn 7] Properties belonging to Reculver in the 7th and 8th centuries are indicated in passing by otherwise unrelated records, such as the estate at Higham, land probably in the High Weald area of Kent, from which iron may have been sourced for use or sale at or on behalf of Reculver, and an unidentified property named Dunwaling land in the district of Eastry.[35] Such records also provide the names of other abbots of Reculver, namely Æthelmær (fl. 699), Bære (fl. 761x764), Æthelheah (fl. 803), Dudeman (fl. 805), Beornwine (fl. 811x826), Baegmund (fl. 832x839), Daegmund (fl. 825x883) and Beornhelm (fl. 867x905).[36]

By the early 9th century the monastery had become "extremely wealthy",[38] but from then on it appears in records as "essentially a piece of property".[39] For most of the period from 764 to 825 Kent was under the control of kings of Mercia, beginning with Offa (757–96), who treated Kent as part of his patrimony: he may also have claimed direct control of Reculver, as he did with similar churches in other areas.[40] In 811 control of the monastery appears to have been in the hands of Archbishop Wulfred of Canterbury, who is recorded as having deprived it of some of its land.[41][42] But by 817 Reculver was in the hands of King Coenwulf of Mercia (796–821), together with the nunnery at Minster-in-Thanet, through which he would also have had strategically lucrative control of the Wantsum Channel:[39] Coenwulf had by then secured a privilege from Pope Leo III that gave him the right to "dispose of his ... monasteries in [England] at will".[43] In that year a "monumental showdown"[39] began between Archbishop Wulfred and King Coenwulf over the control of monasteries, featuring Reculver and Minster-in-Thanet in particular.[39] The dispute over Reculver continued until 821, when Wulfred "made a humiliating submission to [Coenwulf]",[39] surrendering to him an estate of 300 hides, possibly at Eynsham in Oxfordshire, and paying a fine of £120, to secure the return of Reculver and Minster-in-Thanet.[44][Fn 8] The record of the dispute indicates that Wulfred continued to be denied control of Reculver and Minster-in-Thanet after 821 by Cwoenthryth, Coenwulf's heir and abbess of Minster-in-Thanet, until a final settlement was reached at a synod at Clofesho in 825.[46][Fn 9]

From 825 control of Kent fell to the kings of Wessex, and a compromise was reached between Archbishop Ceolnoth and King Egbert in 838, confirmed by his son Æthelwulf in 839, recognising Egbert and Æthelwulf as lay lords and protectors of monasteries and reserving spiritual lordship, particularly over election of abbots and abbesses, to bishops.[48] One copy of the record of this agreement was preserved either at Reculver or at Lyminge.[49] A factor leading to this abandonment of Wulfred's strict policy may have been the increasing intensity of Viking attacks, which had begun in Kent in the late 8th century and had seen the ravaging of the Isle of Sheppey in 835.[50] An army of Vikings spent the winter of 851 on the Isle of Thanet and the same occurred on the Isle of Sheppey in 855.[50] Reculver, like most of the Kentish monasteries, lay in an exposed coastal location, and would have presented an obvious target for Vikings in search of treasure.[51] By the 10th century the monastery at Reculver had ceased to be an important church in Kent and, together with its territory, it was in the hands of the kings of Wessex alone.[52] In a charter of 949 King Eadred of England gave Reculver back to the archbishops of Canterbury, at which time the estate included Hoath and Herne, land at Sarre, in Thanet, and land at Chilmington, about 23.5 miles (37.8 km) south-west of Reculver.[53][Fn 10]

Monastery to parish church

Reculver may have remained home to a religious community into the 10th century, despite its vulnerability to Viking attacks.[55] It is possible that the abbot and community of Reculver took refuge from the Vikings in Canterbury, as the abbess and community of Lyminge did in 804.[56] A monk of Reculver named Ymar was recorded as a saint in the early 15th century by Thomas Elmham, who found the name in a martyrology, and wrote that Ymar was buried in St John’s church, Margate: Ymar was probably killed by Vikings in the 10th century, and hence regarded as a martyr.[57] The Church in East Kent seems broadly to have "preserved its primary ... character against all the odds",[58] but evidence for the monastery at Reculver is lacking: by the 11th century the monastery had "dropped out of sight entirely".[59] The last abbot is recorded as Wenredus: although it is unknown when he was abbot, it must have been after 890 – possibly 905 – when the name of Abbot Beornhelm last appears in Anglo-Saxon charters.[60] The church was last described as a monastery in about 1030, when it was governed by a dean named Givehard and was home to monks, two of whom are named as Fresnot and Tancrad: these names indicate the presence of a religious community from the European continent, probably Flemings.[61] This may have been nothing more than a temporary "resurgence of communal life at Reculver, at least for a period in the earlier eleventh century. ... [Perhaps] the old minster ... was provided as a refuge for a body of foreign clerics".[41]

By 1066 the monastery had become a parish church, with no baptismal function, and its territory had become part of the endowment of the archbishops of Canterbury.[62] Domesday Book records the archbishop's annual income from Reculver in 1086 as £42.7s. (£42.35): this value can be compared with, for example, the £20 due to him from the manor of Maidstone, and £50 from the borough of Sandwich.[63][Fn 11] Included in the Domesday account for Reculver, as well as the church, farmland, a mill, salt pans and a fishery, are 90 villeins and 25 bordars: these numbers can be multiplied four or five times to account for dependents, as they only represent "adult male heads of households".[65][Fn 12]

By the 13th century Reculver parish provided an ecclesiastical benefice of "exceptional wealth",[68] which led to disputes between lay and Church interests.[69] In 1291 the Taxatio of Pope Nicholas IV put the total income due to the rector and vicar of Reculver at about £130.[70][Fn 13] Included in the parish were chapels of ease at St Nicholas-at-Wade and All Saints' Church, Shuart, both on the Isle of Thanet, and at Hoath and Herne.[69] The parish was broken up in 1310 by Robert Winchelsey, archbishop of Canterbury from 1294 to 1313, who created parishes from Reculver's chapelries at Herne and, on the Isle of Thanet, St Nicholas-at-Wade and Shuart, in response to the difficulties posed by the distance between them and their mother church at Reculver, and a "steady increase in population".[72][Fn 14] At this time Shuart became part of St Nicholas-at-Wade parish, and its church was later demolished.[74] However, St Mary's Church, Reculver, continued to receive payments from the parishes of Herne and St Nicholas-at-Wade in the 19th century as a "token of subjection to Reculver",[75] as well as for the repair of St Mary's Church, and the parish retained a perpetual curacy at Hoath until 1960.[76][Fn 15]

Enlargement and decline

Enlargement

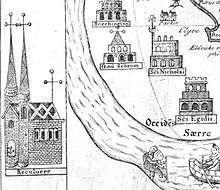

The church building was considerably enlarged over time. The outer walls of the north and south porticus were extended to enclose the nave in the 8th century, forming a series of rooms, including chapels on both northern and southern sides, and a porch across the western side. The towers were added as part of an extension with a new west front in the late 12th century, when the internal walls of the rooms added in the 8th century were demolished, creating aisles on the north and south sides of the nave. In the 13th century the original apse was demolished and the chancel more than doubled in size, incorporating a triple east window with columns of Purbeck Marble, and in the 15th century north and south porches were added to the nave.[79][Fn 16] A chantry in the church was endowed in 1354 in memory of Alicia de Brouke, and two more were endowed in 1371 by Thomas Niewe, a former vicar of Reculver.[80] These chantries were suppressed in the reign of Edward VI, in 1548 or very early in 1549.[81][Fn 17] The towers were topped with spires by 1414, since they are shown in an illustrated map drawn by Thomas Elmham in or before that year, and the north tower held a ring of bells.[83][Fn 18] The addition of the towers, "an extraordinary investment ... for a parish church",[92] and the extent to which the church was enlarged in the Middle Ages, suggest that "a thriving township must have developed nearby."[93] Despite all the building work, the church retained many prominent Anglo-Saxon features, and one in particular roused John Leland to "an enthusiasm which he seldom displayed" when he visited Reculver in 1540:[94]

Yn the enteryng of the quyer ys one of the fayrest and the most auncyent crosse that ever I saw, a ix footes, as I ges, yn highte. It standeth lyke a fayr columne. The base greate stone ys not wrought. The second stone being rownd hath curiously wrought and paynted the images of Christ, Peter, Paule, John and James, as I remember. Christ sayeth [I am the Alpha and the Omega]. Peter sayeth, [You are Christ, son of the living God]. The saing of the other iij when painted [was in Roman capitals] but now obliterated. The second stone is of the Passion. The third conteineth the xii Apostles. The iiii hath the image of Christ hanging and fastened with iiii nayles and [a support beneath the feet]. the hiest part of the pyller hath the figure of a crosse.— John Leland, "Itinerary", 1540[95]

The high cross Leland is describing had been removed from the church by 1784.[96][Fn 19] Archaeologists examined what was believed to be the base of a 7th-century cross in 1878 and the 1920s, and it has been suggested that the monastery at Reculver was originally built around it.[98] The Reculver cross has been compared with the Anglo-Saxon Ruthwell Cross – an open-air preaching cross in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland[99] – and traces of paint on fragments of the Reculver cross show that its details were once multicoloured.[100] Later, stylistic assessments indicate that the cross, carved from a re-used Roman column, probably dates from the 8th century or the 9th, and that the stone believed to have been the base may have been the foundation for the original, 7th-century altar.[101][Fn 20] Leland also reported a wall painting of an unidentified bishop, on the north side of the church under an arch.[95] Another Anglo-Saxon item Leland found in the church was a gospel book: this was

'a very auncient boke of the Evangelyes [in Roman capital letters] and in the bordes thereof ys a christal stone thus inscribid: CLAUDIA . ATEPICCUS'. A gospel book written in 'Roman majuscules' is unlikely to have been later than the early ninth century: perhaps it was an Italian import, such as the celebrated sixth-century manuscript known as the 'Gospels of St Augustine' (CCCC 286), but it could also have been a native product, of the seventh to ninth century, written in uncial or half-uncial, such as the 'Royal Gospels' from St Augustine's (BL Royal I E VI). It appears to have had a lavish binding decorated with a Roman cameo.— Susan Kelly, "Reculver Minster and its early charters", 2008[106]

In its final form, the church consisted of a nave 67 feet (20.4 m) long by 24 feet (7.3 m) wide, with north and south aisles of the same length and 11 feet (3.4 m) wide, and a chancel 46 feet (14 m) long by 23 feet (7 m) wide. Including the spires, the towers were 106 feet (32.3 m) high, the surviving towers alone reaching 63 feet (19.2 m). The towers measure 12 feet (3.7 m) square internally, and are connected internally by a gallery which was about 25 feet (7.6 m) above the floor of the nave. The overall length of the church was 120 feet (36.6 m), and the breadth of the west front, which also survives, is 64 feet (19.5 m).[107]

Decline

When Leland visited Reculver in 1540, he noted that the coastline to the north had receded to within little more than a quarter of a mile (402 m) of the "Towne [which] at this tyme [was] but Village lyke".[109] Soon after, in 1576, William Lambarde described Reculver as "poore and simple".[110] In 1588 there were 165 communicants – people in Reculver parish taking part in services of holy communion at the church – and in 1640 there were 169,[9] but a map of about 1630 shows that the church then stood only about 500 feet (152 m) from the shore.[111][Fn 21] In January 1658 the local justices of the peace were petitioned concerning "encroachments of the sea ... [which had] since Michaelmas last [29 September 1657] encroached on the land near six rods [99 feet (30 m)], and will doubtless do more harm".[112] The village's failure to support two "beer shops" in the 1660s points clearly to a declining population,[113] and the village was mostly abandoned around the end of the 18th century, its residents moving to Hillborough, about 1.25 miles (2 km) south-west of Reculver but within Reculver parish.[114]

The decline of the settlement led to the decline of the church. In 1776 Thomas Philipot described it as "full of solitude, and languished into decay".[115] In 1787 John Pridden noticed that the roofline of the nave must have been lowered at some time, judging by the tops of the east and west walls, and the fact that the tops of the two windows over the west door were at that time filled in with brick; he also noted that the roof had been repaired in 1775 by A. Sayer, churchwarden, these details appearing embossed on replacement lead.[116] But he described the church as "a weather-beaten building ... mouldering away by the fury of the elements",[117] and a letter to The Gentleman's Magazine in 1809 said that it was then somewhat dilapidated, with "trifling ... repairs such as have only tended to obliterate its once-harmonizing beauties."[118]

Destruction

In the autumn of 1807 a northerly storm combined with a high tide to bring erosion of the cliff on which the church stood to within the churchyard, destroying "ten yards [9.1 m] of the wall around the churchyard, not ten yards from the foundation of the church".[119] Sea defences had been in place since at least 1783, but although they had been costly to build their design had led to further undermining of the cliff.[120] Two further schemes were devised by Sir Thomas Page and John Rennie to preserve the cliff by means of new sea defences, Rennie's being estimated to cost £8,277.[121] Instead, at a vestry meeting on 12 January 1808, and at the instigation of the vicar, Christopher Naylor, it was decided that the church should be demolished.[122][Fn 22] The decision was reached by vote among eight of the leading residents of Reculver and Hoath, including the vicar: the votes were evenly split, so the vicar used his casting vote in favour of demolition.[125][Fn 23] Naylor applied to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Charles Manners-Sutton, for permission to demolish, arguing that "in all human probability the parishionsers [would] shortly be deprived of a place for the interment of their dead."[127] The archbishop commissioned neighbouring clergy and landowners to assess the situation, and they reported in March 1809 that the church should be demolished "to save the materials for the erection of another church."[128][Fn 24]

Demolition was begun in September 1809 using gunpowder, in what has been described as "an act of vandalism for which there can be few parallels even in the blackest records of the nineteenth century":[129][Fn 25]

the young clergyman of the parish, urged on by his Philistine mother, rashly besought his parishioners to demolish this shrine of early Christendom. This they duly did and all save the western towers, which still act as a landmark for shipping, was razed to the ground.— Nigel & Mary Kerr, A Guide to Anglo-Saxon Sites, 1982[133]

The demolition of this "shrine of early Christendom", and exemplar of Anglo-Saxon church architecture and sculpture,[14] was otherwise thorough, and it is now represented only by the ruins on the site, material incorporated into a replacement parish church at Hillborough,[134] fragments of the cross, and the two stone columns which had been part of the church's triple arch. The columns and fragments of the cross are on display in Canterbury Cathedral.[135][Fn 26] Two thousand tons of stone from the demolished church were sold and incorporated into the harbour wall at Margate, known as Margate Pier, which was completed in 1815, and more than 40 tons of lead was stripped from the church and sold for £900.[136][Fn 27] Trinity House bought what was left of the structure from the parish for £100, to ensure that the towers were preserved as a navigational aid, and built the first groynes, designed to protect the cliff on which the ruins stand.[140][Fn 28] The spires had both been destroyed by storms by 1819, when Trinity House replaced them with similarly shaped, open structures, topped by wind vanes.[142][Fn 29] These structures remained until they were removed some time after 1928.[144] The ruins of the church, and the site of the Roman fort within which it was built, are now in the care of English Heritage,[145] and the sea defences protecting the church continue to be maintained by Trinity House.[146]

Archaeology

The first archaeological report on the then demolished church of St Mary was published by George Dowker in 1878.[148] He described finding the foundations of the apsidal chancel and of the columns that formed part of the triple chancel arch, and noted that the original floor of the church was of concrete, or opus signinum, more than 6 inches (15 cm) thick.[149] The floor had previously been described in 1782, prior to the church's demolition, as polished smooth and finished in red, a sample having been taken with difficulty using a pickaxe.[150] Within the floor Dowker also found what he believed were the foundations for the stone cross described by Leland, and noted that the concrete floor appeared to have been laid around them.[151] The floor of the chancel appeared to have been raised by about 10.5 inches (26.7 cm) when the chancel was extended in the Early English period, and had been covered with encaustic tiles.[151] Dowker also reported hearing from a Mr Holmans about the existence of a large, circular burial vault at the east end of the chancel, containing coffins arranged in a circle.[152][Fn 30]

Further excavations were undertaken in the 1920s by C. R. Peers, who found that the nave of the original church had external doors on the north, south and west sides, and that the chancel had doors leading into the north and south porticus, which in turn had external doors on their eastern sides.[22][Fn 31] Regarding the floor described by Dowker, Peers noted that the surface consisted of a thin layer of pounded brick, and believed that it was of the same date as the stone which Dowker described as the foundations for the stone cross.[156] Excavations also revealed steps leading down to the burial vault reported by Dowker, although Peers did not refer to either the steps or the vault in his report.[157][Fn 32] Extensions of the porticus to the west and around the original west front were dated to no more than 100 years after the church was first built, and Peers observed that these extensions had been given the same type of floor as the original church.[158] Drawing comparisons with the 7th-century chapel of St Peter-on-the-Wall at Bradwell-on-Sea, in Essex, and the abbey of St Augustine at Canterbury, Peers suggested that the original church at Reculver probably had windows set high in the northern and southern walls of the nave.[159] Areas of wall found by archaeologists but now missing above ground are marked on the site by strips of concrete edged with flint.[160][Fn 33]

The church was found to have been free-standing, so any other monastic buildings must have stood apart.[158] In 1966, archaeologists discovered the foundations of what they identified as probably a medieval building, rectangular and on an east-west axis, with its eastern wall aligned with that of the church precinct, which it pre-dated.[162] Extending over and in contact with the western end of a Roman bath house, it stood a few yards east of the south-eastern corner of the 13th-century chancel. This building was not recorded by William Boys, who drew a plan of the Roman fort and the church in 1781.[163] Otherwise no such buildings have been found, but they may all have been in the area to the north of the church, which has been lost to the sea.[164] In this connection Peers noted that the cloisters of the early Canterbury churches of St Augustine's and Christ Church were both on their northern sides.[165] A building that stood west-northwest of the church may have had an Anglo-Saxon doorway and the dimensions of an Anglo-Saxon church, and had "the appearance of having been part of some monastic erection".[166] It was demolished after the sea weakened its foundations during storms in the winter of 1782.[167] Leland reported another building outside the churchyard, where it was believed that a parish church had stood while the main church at Reculver was still a monastery:[95] this building, formerly a chapel dedicated to St James, was later known as the "chapel-house", and stood in the north-eastern corner of the fort until it collapsed into the sea on 13 October 1802.[168] Peers noted further that it seems to have had brick arches.[169][Fn 34]

St John's Cathedral, Parramatta

St_Johns_Cathedral_Parramatta.jpg)

The design of the twin towers, spires and west front of St John's Cathedral, Parramatta, in Sydney, Australia, which were added in 1817–1819, is based on those of St Mary's Church at Reculver.[170] Efforts to save St Mary's Church were still under way when Governor Lachlan Macquarie and his wife Elizabeth left England for Australia in 1809. Elizabeth Macquarie asked John Watts, the governor's aide-de-camp from 1814 to 1819, to design the towers for St John's Cathedral, and these, together with its west front, are the oldest remaining parts of an Anglican church in Australia, and are on the oldest site of continuous Christian worship there.[170][Fn 35] In 1990 a stone from Reculver was presented to St John's Cathedral by the Historic Building and Monuments Commission for England, now English Heritage.[172]

References

Footnotes

- ↑ The "A" manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, also known as the "Parker Chronicle", records that Bassa was a "mass-priest".[3] According to Susan Kelly, "[h]e would have been a senior clergyman: a 'mass-priest' was ... a cleric who had attained the highest of the seven appointed orders and was thus qualified to celebrate the mass."[4] Hussey 1852, p. 135, regards Bassa the priest as identical with the Northumbrian warrior Bassus who, according to Bede, had accompanied Paulinus of York and Æthelburh of Kent to Kent after the death of her husband King Edwin of Northumbria: this occurred in 633, 36 years before the foundation of the church at Reculver.[5] Susan Kelly also references Bede in this connection, but only to indicate that Bassa's name was then current in England: she similarly refers to English place-names containing the same personal name.[6]

- ↑ According to Hasted 1800, King Ecgberht gave Reculver for the establishment of a monastery "as an atonement for the murder of his two nephews [sons of Eormenred of Kent]",[9] but Kelly 2008 does not refer to this, instead placing the church's establishment in the context of domination of the early Kentish church by "non-native" leaders and observing that "[perhaps] it is no coincidence that in the year of Theodore's arrival [from Rome] King Ecgberht was involved in the establishment of a house of male religious [at Reculver] in a strategic location outside Canterbury. ... It may be significant that the next archbishop after the death of Theodore in 690 was Berhtwald, abbot of Reculver by 679 and perhaps Bassa's immediate successor."[10] John Blair suggests that Reculver's foundation may have been prompted by Wilfrid.[11]

- ↑ An English Heritage information plaque for visitors to the site of the church, headed "An Anglo-Saxon Church", shows a reconstruction of the original church of Reculver, with monks robed in black in the chancel; a similar image is at Wilmott 2012, p. 24. Triple arches also featured in the near-contemporary churches of St Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury, and St Peter-on-the-Wall, Bradwell-on-Sea, Essex, and at Lyminge, in Kent.[18]

- ↑ The inclusion of porticus at Reculver in the 7th century was described in 1965 as being "without parallel in western Europe,"[19] except among contemporary churches in Kent and at the church of St Peter-on-the-Wall, Bradwell-on-Sea, Essex,[20] but more recent analysis has shown that porticus were probably more common in early Anglo-Saxon churches.[18]

- ↑ The charter, S 8, uses the dative form of the Latin word "monasterium", and is the earliest genuine Anglo-Saxon charter known to have survived in its original form.[24]

- ↑ Berhtwald is regarded as a saint, "apparently based on a single late calendar of St Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury".[30]

- ↑ In her 2004 entry for Æthelberht II in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Susan Kelly wrote that Eadberht I of Kent was buried at Reculver "in 748".[33] However, in Kelly 2008, she observes that there is "a much better context"[34] for this royal burial to have been of Eadberht II, who "faded from view c. 763 x 764".[32] The royal tomb at Reculver was "in a position corresponding to the south porticus (at St Augustine's kings were buried in the south porticus); an inscription or other record identifying [the occupant] as King Eadberht (grand-)son of King Æthelberht may have given rise to the later belief that it was the earlier King Æthelberht himself that was buried [at Reculver]."[32] Ward 1946, p. 27, believes that, instead of Sheldwich, a grant was made of land at Shelvingford near Hoath, but this is not supported by e.g. Glover 1976, pp. 170–1.

- ↑ According to Nicholas Brooks, 300 hides was "almost as much as the entire archiepiscopal holding in Kent at the time of the Domesday survey [in 1086.] ... [T]he huge sum of £120 ... [was] in Mercian law ... the amount that had to be paid as the blood-price or wergild of a king."[45]

- ↑ By 826 Cwoenthryth "would seem either to have died, or more probably to have resigned as abbess of [Minster-in-Thanet]."[47]

- ↑ It may be that the estate was previously in the possession of Eadgifu, King Eadred's mother, and that it was bought from her by Archbishop Oda.[54] The land at Chilmington was "probably a recent gift to the church."[41]

- ↑ Of the £42.7s. from Reculver, £7.7s. (£7.35) was from an unspecified source. While Hoath, Herne and western parts of the Isle of Thanet were Reculver possessions in the Anglo-Saxon period, and remained attached to Reculver long after 1086, of these only Reculver is named in Domesday Book: "[as] the name [Reculver] is used here, it means something larger than the parish but much smaller than the thirteenth-century manor of Reculver. It is fairly sure to have included Hoath ...; it may also have included the adjoining part of Thanet, [including Shuart] ... and St Nicholas-at-Wade ... [The separate manor of Nortone is] Herne ... under another name."[64]

- ↑ The multiplication indicated by Eales would give a peasant population for the whole of the estate centred on Reculver in 1086 of 460–575 people. The mill was probably a watermill, near Brook Farm, and King Eadred's charter of 949 refers to a mill-creek in the area.[66] There are numerous medieval salt working sites in the area to the south and east of Reculver, many of which lie on land belonging to Reculver in the medieval period, for example at TR23316797.[67]

- ↑ From 1310, the rector of Reculver was the archbishop of Canterbury.[71]

- ↑ In 1274–75, the jurors of Bleangate hundred, in which Reculver then lay, reported that it had lately been made more difficult for the people of Thanet to reach the mainland: while previously access had been provided by a "wall", this had been cut off by a ditch dug for the abbot of St Augustine's, Canterbury.[73]

- ↑ In 1918 it was reported that a seal matrix had been discovered in the previous year "just to the south-east of the ruined church."[77] The seal matrix dates to the early 14th century, and bears the inscription "S[igillum] Vicarii de Reiculvre", or "Seal of the Vicar of Reculver". It was probably created in connection with the grant of the peculiar status of rural dean to Nicholas Tingewick, physician to King Edward I and rector of Reculver until 1310, when he became Reculver's first recorded vicar.[78]

- ↑ Ground plans showing the development of the church from the 7th century to the 15th are at Wilmott 2012, pp. 24–5.

- ↑ The chantry priests are listed at Duncombe 1784, p. 158: the last chantry priest, Thomas Hewet, was drawing a pension of £6 in 1556.[82]

- ↑ According to legend the towers were topped with spires early in the 16th century,[84] and the legend gave rise to a by-name of the "Twin Sisters", in reference to a prioress of Davington and her sister.[85] George Dowker wrote in 1878 that "[i]t is probable that there is some basis [for the legend], as the architectural features of the towers [of St Mary's Church, Reculver,] would agree well with [the date of Davington Priory's foundation in 1156]."[86] The west front of Davington Priory originally had two towers,[87] and in 1966 Robert H. Goodsall drew attention to the similarity between these and the towers at Reculver.[88] A bell from the church was reported sold in 1606, and in 1683 it was reported that the ring of bells was in need of repair.[89] Four bells were reported present by Francis Green, vicar of Reculver from 1695 to 1716, and by Bryan Faussett in 1758: Faussett added that they had been made in 1635 by Joseph Hatch.[90] He also cast the bell known as "Bell Harry" at Canterbury Cathedral.[91]

- ↑ The cross probably stood until the English Reformation, when it was "presumably destroyed by sixteenth-century iconoclasts [after which] nothing more is recorded of it."[97]

- ↑ According to E.M. Jope, "[s]ome later 7th- or early 8th-century work ... contains a few blocks of freestone less likely to have been found among Roman ruins ... [Fine] stone from northern France was used for the cross-head".[102] Susan Kelly regards it as "probable that it was against [the] complicated background [of Mercian control of Kentish monasteries early in the 9th century] that the Reculver cross was carved from an old Roman column and erected behind the altar before the chancel arch. A date in the early ninth century is certainly implied by ... Carolingian parallels and the stylistic evidence ... There was a strong Mercian tradition of stone sculpture in the eighth century (in Wessex this craft did not develop until the ninth), so it is tempting to suspect that the cross was set up while Reculver was under the control of the Mercian kings. The minster at Winchcombe in Gloucestershire [was] closely associated with King Coenwulf and his family ... The erection of a massive cross [at Reculver] perhaps reflected Winchcombe influence."[103] The classicist Martin Henig notes that a Christian church and a baptismal font dating from Roman times have been identified at nearby Richborough (Rutupiae), and considers it possible that there may have been Christian churches replacing pagan aedes in other Saxon Shore forts, such as that at Reculver, where an aedes is known to have existed;[104] he also suggests that the Reculver cross could have been a replacement for an earlier, "Christianised Roman monument",[105] for example a re-used Jupiter column, as may have happened at Canterbury Cathedral and in Trigg, in Cornwall.[104] A reconstruction of the Reculver cross is at Kozodoy 1986, p. 86, Figs. 3 & 4, and this is reproduced at Canterbury City Council 2008, p. 5. A reconstruction showing only the front of the cross is at Wilmott 2012, p. 44.

- ↑ Part of this map is illustrated in Dowker 1878, facing page 8.

- ↑ Taylor 1968, p. 291, gives the year in which the decision was made to demolish the church as 1802, Fletcher 1965, p. 24, and Kelly 2008, p. 67, give it as 1805, and Wilmott 2012, p. 45, gives it as 1807, but, while the chronology set out in Gough 2014 indicates a date in late 1807 or early 1808, the relevant article in The Literary Panorama is in a section headed "For March, 1808",[123] is dated "January 17", and states that the vestry meeting was held "on Tuesday last".[124]

- ↑ A record of events written by John Brett, parish clerk, states that, from 1802, "peopel [sic] come from all parts to see the ruines of village and the church Mr C B Nailor been vicar of the parish his mother fanced that the church wos keep for a poppet show and she persuade har son to take it down":[126] Brett, who had been parish clerk for 40 years, voted against demolition, and wrote of the vicar, "whot wos [his thoughts] about [his] flock that day no one knows".[126]

- ↑ The commissioners were the rector of Staplehurst, Robert Parry, the vicar of Willesborough, John Francis, and George May, John Ashbee and John Collard, all of Herne.[128]

- ↑ Sources frequently date the church's demolition to 1805,[130] but a meeting to discuss the church's future was held at the church on 12 January 1808;[124] a detailed description of the standing church, including pleas for its preservation, was submitted to The Gentleman's Magazine on 3 March 1809;[118] The Gentleman's Magazine reported in 1809 and 1856 that the church's demolition began in September 1809;[131] and the year of the church's demolition is given as 1809 in Blair 1999 and in the archive of Canterbury Cathedral.[132]

- ↑ An aerial view of the ruins is at Witney 1982, Plate 8.

- ↑ Lead from the spires and roof of the church was offered for sale in the Kentish Gazette on 14 July 1809.[137] Gough 1995, p. 10, says that "lead from the roof and spires was sold to Joseph Day of London for £860.8s.0d. [£860.40] at a rate of £25.10s.0d. [£25.50] per ton." Tenders were invited for the transport of large quantities of stone from Reculver to Margate on 2 June 1810.[138] In 1887, J.C.L. Stahlschmidt wrote that one of the bells made by Joseph Hatch in 1635 was re-used in the new church at Hillborough and another in St Leonard's Church, Badlesmere, Kent: "the others, probably, ... [were] melted."[139]

- ↑ Trinity House also repaired the towers' buttresses, and filled in the church's west door, with brick.[141]

- ↑ A stone tablet incorporated into the church ruins reads: "These Towers the Remains of the once venerable Church of Reculvers, were purchased of the Parish by the Corporation of Trinity House, of Deptford Strond in the Year 1810, and Groins laid down at their Expence, to protect the Cliff on which the Church had stood. When the ancient Spires were afterwards blown down, the present Substitutes were erected, to render the Towers still sufficiently conspicuous to be useful to Navigation. Captn. Joseph Cotton, deputy Master in the year 1819."[142] An anonymous engraving from 1812, entitled "N.E. View of Reculver Church, Kent, 1812", shows the church in ruins and only one of the spires remaining.[143]

- ↑ Letters were addressed to a Mr and Mrs Holman at Reculver in 1862 and 1869,[153] and a Mr John Holman was a farmer at Reculver in 1877 and 1878.[154] In a letter dated 7 May 1595, Archbishop John Whitgift of Canterbury gives his permission for Sir Cavalliero Maycote to create a burial vault for his family in the chancel at Reculver.[155]

- ↑ According to Kelly 2008, p. 67(note), Peers' work is "the standard archaeological account of the church".

- ↑ The location of the steps is illustrated at Peers 1927, p. 245, and Jessup 1936, p. 181.

- ↑ A photograph at Canterbury City Council 2008, p. 6, "View of late Norman ruins looking east", shows the curve of the 7th-century apse marked by a strip of concrete edged with flint. The burial vault reported at Dowker 1878, p. 261, lies between the apse and the further, eastern wall of the chancel. Two circles of concrete in the central area of grass mark the locations of the two columns which were part of the triple chancel arch, in front of which stood the stone cross. To the left and right of the concrete circles, the outlines of the 7th-century porticus can be seen, with gaps for the east-facing external doors: the standing walls beyond the doorways date to the 13th century.[161]

- ↑ In 1800 these buildings were described as follows: "[An] ancient gothic building, formerly the chapel of St. James, and belonging to the hermit of Reculver. It is now converted into a cottage, the walls of which are mostly composed of Roman bricks, and in the wall is an arch entirely so. [And] a small house, which has a religious gothic appearance, and is supposed to have been formerly the dwelling of the hermit, and king Richard II in his 3d year, granted a commission to Thomas Hamond, hermyte of the chapel of St. James, &c. being at our lady of Reculver, ordeyned for the sepulture of such persons as by casualtie of stormy or other misadventures were perished to receive the alms of charitable people for the building of the roof of the chapel fallen down."[9]

- ↑ "Mrs Elizabeth Macquarie showed Lieutenant John Watts, Aide De Camp of the 46th Regiment a watercolour of the church and asked him to design some towers for [St John's, Parramatta]. A watercolour of Reculver Church in the [Mitchell Library section of the State Library of New South Wales] has a note in Macquarie's hand that he laid the foundation stone on 23 December 1818. Mrs Macquarie chose the plan and Lt. Watts was responsible for implementing the design".[170] In the watercolour, the sea is shown washing against the cliff, and the spires of Reculver church have been replaced by the Trinity House wind vanes; the accompanying note is annotated with a reference to Jervis, J. (1935), "Parramatta During the Macquarie Period", Journal and Proceedings 4, Parramatta Historical Society, p. 163, saying that the note is "evidently a copy of what was evidently intended as an inscription upon the foundation stone of the towers of the Parramatta Church".[171] The "46th Regiment" was the 46th (South Devonshire) Regiment of Foot.

Notes

- ↑ Kelly 2008, p. 74.

- ↑ Garmonsway 1972, pp. 34–5; Fletcher 1965, pp. 16–31; Page 1926, pp. 141–2; Kelly 2008, pp. 71–2.

- ↑ Earle 1865, p. 34; "Manuscript 173 : - f. 8 R". Parker Library on the Web. Stanford University. n.d. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, pp. 71–2.

- ↑ Bede 1968, pp. 138–9.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, pp. 71–2 & note.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, p. 71.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, pp. 72–3; Lapidge 1999, p. 225.

- 1 2 3 Hasted 1800, pp. 109–25.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, pp. 72–3.

- ↑ Blair 2005, p. 95.

- ↑ Kelly 1992, p. 4; Kelly 2008; Brooks 1984, p. 399.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, p. 187.

- 1 2 Blair 1999, p. 386.

- ↑ Philp 2005, p. 204.

- ↑ Fletcher 1965, p. 24; Harris 2001, p. 34.

- ↑ Haverfield & Mortimer Wheeler 1932, p. 21; Roach Smith 1850, p. 197.

- 1 2 Cherry 1981, p. 163.

- 1 2 Fletcher 1965, p. 26.

- ↑ Fletcher 1965, pp. 26, 30.

- ↑ Fletcher 1965, pp. 24, 27–30.

- 1 2 Peers 1927, p. 244.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, p. 74; "S 8". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, p. 98, Fig. 96.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, pp. 74–5.

- ↑ Blair 2005, p. 249; Kelly 2008, p. 74.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, pp. 76–80; Kelly 2008, p. 77.

- ↑ Bede 1968, p. 282.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, p. 76.

- ↑ Farmer 1992, p. 50.

- ↑ Page 1926, pp. 141–2; Kelly 2008, p. 78; "S 31". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015; "S 1612". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015; "S 38". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 Kelly 2008, pp. 78–9.

- ↑ "Æthelberht II". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52310. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.). Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, p. 79.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, pp. 76–8, 80.

- ↑ Ward 1946, pp. 26–8.

- ↑ Roach Smith 1850, p. 197.

- ↑ Blair 2005, p. 123.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kelly 2008, p. 80.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, pp. 112–4; Yorke 1990, pp. 31–2; Kelly 2008, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 Kelly 2008, p. 82.

- ↑ "S 1264". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ↑ Yorke 1990, p. 118; Levison 1946, pp. 31–2.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, pp. 180–97; Blair 2005, pp. 130–1; Kelly 2008, p. 80.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, p. 182.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, p. 182; Yorke 2003, p. 56; "S 1436". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, p. 197.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, pp. 194–9.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, p. 199.

- 1 2 Brooks 1984, p. 201.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, pp. 201–2.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, p. 81.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, pp. 232–6; Gough 1992; Kelly 2008, p. 82; "S 546". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, pp. 232–6.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, pp. 81–2; Brooks 1979, pp. 1–20 (esp. 12); Brooks 1984, pp. 203–4; Kerr 1982, pp. 192–94.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, p. 163; Kelly 2008, p. 81.

- ↑ Hardwick 1858, p. 223; Cotton 1929, p. 74.

- ↑ Blair 2005, p. 299.

- ↑ Brooks 1984, p. 203–5.

- ↑ Dodsworth & Dugdale 1655, p. 26;Duncombe 1784, p. 87(note); Ward 1946, p. 28.

- ↑ Blair 2005, p. 361; Kelly 2008, p. 82; "S 1390". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, pp. 74, 82; Brooks 1984, pp. 203–5; Gough 1992.

- ↑ Williams & Martin 2002, p. 8.

- ↑ Flight 2010, p. 162.

- ↑ Eales 1992, p. 21.

- ↑ Gough 1992, pp. 94–5; Kelly 2008, p. 74; "S 546". The Electronic Sawyer. King's College London. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Exploring Kent's Past (n.d.). "Medieval Saltmound". Kent County Council. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ Graham 1944, p. 1.

- 1 2 Graham 1944, pp. 1–12.

- ↑ Denton, J.; et al. (2014). "Benefice of Reculver (CA.CA.WE.05)". HRI Online. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ Hasted 1800, pp. 109–25; Duncombe 1784, p. 78 & note.

- ↑ Gough 1992, pp. 91–2; Hasted 1800, pp. 109–25; Bagshaw 1847, p. 217.

- ↑ Jones 2007, Bleangate.

- ↑ Gough 1992, pp. 91–2.

- ↑ Bagshaw 1847, p. 225.

- ↑ Graham 1944, pp. 10–1; Hasted 1800, pp. 109–25; Lewis 1848, pp. 645–52; Hussey 1902, passim; Bagshaw 1847, pp. 217, 225; "The Archbishop of Canterbury has appointed ...". The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 2 July 1917. Retrieved 9 May 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)); "Reculver". Whitstable Times and Herne Bay Herald. 28 October 1922. Retrieved 9 May 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)); "Curate's suicide". Dover Express. 22 May 1931. Retrieved 8 May 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)); Gough 1995, p. 8.

- ↑ Clinch 1918, p. 169.

- ↑ Clinch 1918, pp. 169–70; Duncombe 1784, p. 154; "Nicholas Tingewick". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/52684. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- ↑ Peers 1927; Jessup 1936, pp. 180–3; Wilmott 2012, p. 26.

- ↑ Duncombe 1784, p. 157; Hussey 1917, p. 85.

- ↑ Dowker 1878, p. 252.

- ↑ Flaherty 1859, p. 62.

- ↑ Rollason 1979, p. 7; Rollason 1982, p. 10; Duncombe 1784, p. 127; Torr, V.J. (2008). "Some Monumental Inscriptions of St Mary's Church, Reculver, Noted by Rev Bryan Faussett: Noted 1758". Kent Archaeological Society. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015..

- ↑ Jessup 1936, p. 179–80.

- ↑ Hasted 1800, pp. 109–25; Jessup 1936, p. 179; Anon. 1791, pp. 97–104.

- ↑ Dowker 1878, pp. 256-7.

- ↑ Willement 1862, p. 32(note).

- ↑ Goodsall 1981, pp. 65–7, photograph & reconstruction between pp. 64 & 65.

- ↑ Hussey 1902, pp. 46, 56.

- ↑ Duncombe 1784, pp. 127, 156; Torr, V.J. (2008). "Some Monumental Inscriptions of St Mary's Church, Reculver, Noted by Rev Bryan Faussett: Noted 1758". Kent Archaeological Society. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2015.; Stahlschmidt 1887, p. 377.

- ↑ Furley 1874, p. 595; Stahlschmidt 1887, pp. 75–6; Goodsall 1970, pp. 33–4.

- ↑ Canterbury City Council 2008, p. 6.

- ↑ Gough 2014; Wilmott 2012, p. 26.

- ↑ Graham 1944, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Hearne 1711, p. 137.

- ↑ Duncombe 1784, p. 72.

- ↑ Peers 1927, p. 251.

- ↑ Dowker 1878, pp. 259–60; Peers 1927, pp. 241–56; Exploring Kent's Past (n.d.). "Anglo-Saxon Minster and the ruins of St Mary's Church". Kent County Council. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Jessup 1936, pp. 185–6.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, pp. 68–9.

- ↑ Cherry 1981, p. 163; Kelly 2008, pp. 69, 80–1.

- ↑ Jope 1964, p. 98.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, pp. 80–1.

- 1 2 Henig 2008, pp. 193–4.

- ↑ Henig 2008, p. 194.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, p. 69.

- ↑ Freeman 1810, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Pridden 1787, Plate IX.

- ↑ Hearne 1711, p. 137; Jessup 1936, p. 187.

- ↑ Lambarde 1596, p. 207.

- ↑ Jessup 1936, p. 189.

- ↑ Gough 2002, p. 204.

- ↑ Gough 2014.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, p. 67; Harris 2001, p. 36.

- ↑ Philipot 1776, p. 278.

- ↑ Pridden 1787, p. 165 & Plate IX.

- ↑ Pridden 1787, p. 164.

- 1 2 Mot 1809, pp. 801–2.

- ↑ Gough 2014; Anon. 1808, col. 1310.

- ↑ Duncombe 1784, pp. 77, 90(note).

- ↑ Duncombe 1784, pp. 77, 90(note); Anon. 1808, col. 1310; Anon. 2011, p. 56.

- ↑ Gough 1983, p. 135; Anon. 1808, col. 1310; Gough 2001, p. 137; Gough 2014; Wilmott 2012, p. 45.

- ↑ Taylor 1808, cols. 1129–30.

- 1 2 Anon. 1808, col. 1310.

- ↑ Gough 1983, pp. 133–4.

- 1 2 Gough 1983, p. 135.

- ↑ Gough 1995, pp. 9–10.

- 1 2 Gough 1995, p. 10.

- ↑ Campbell 1982, p. 107, Figs. 99 & 100, quoting Taylor, H.M & J. (1965), Anglo-Saxon Architecture 2, Cambridge, p. 503; Cozens 1809, p. 906; Anon. 1856, p. 315; Canterbury Cathedral Archives (2012). "Reculver, St Mary Parish Records". Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral. Archived from the original on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2015; Harris 2001, p. 36.

- ↑ Fletcher 1965, p. 24; Jessup 1936, p. 182; Kerr 1982, p. 194; Kelly 2008, p. 67; Kozodoy 1986, p. 68; "History of Reculver Towers and Roman fort". English Heritage. n.d. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Cozens 1809, p. 906; Anon. 1856, p. 315.

- ↑ Canterbury Cathedral Archives (2012). "Reculver, St Mary Parish Records". Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral. Archived from the original on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Kerr 1982, p. 194.

- ↑ Jessup 1936, p. 184; Exploring Kent's Past (n.d.). "Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin, Hillborough". Kent County Council. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Canterbury City Council 2008, p. 5.

- ↑ Wilmott 2012, p. 45; Cozens 1809, p. 906; C. of Kent 1810, p. 204; Anon. 1856, p. 315; thanetarch (2006). "Margate Pier – The Pier Structure". Museum of Thanet. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ "Lead to be sold by private contract". Kentish Gazette. 14 July 1809. Retrieved 5 May 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Chancellor, J. (8 June 1810). "Tenders for freight of stone, from Reculver to Margate". Kentish Gazette. Retrieved 8 May 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Stahlschmidt 1887, pp. 143, 307, 377.

- ↑ Jessup 1936, p. 187; Crudgington, L. (18 March 2014). "Modern church proud of links to Roman times". Canterbury Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Dowker 1878, p. 257.

- 1 2 Jamesjhawkins (2011). "Reculver towers plaque". Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ↑ "Picture No. 10238753". TipsImages. 2012. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ↑ Jessup 1936, Plate I.

- ↑ Days Out in England (n.d.). "Reculver Towers and Roman Fort". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Wilmott 2012, p. 26.

- ↑ Peers 1927, fig. 4.

- ↑ Dowker 1878.

- ↑ Dowker 1878, pp. 259–60, 263–4; Taylor 1968, p. 294, quoting Clapham 1930, p. 62.

- ↑ Duncombe 1784, p. 88.

- 1 2 Dowker 1878, pp. 259–60.

- ↑ Dowker 1878, p. 261.

- ↑ Anon. 1999, pp. 189–90.

- ↑ "Charge of stealing barley at Reculver". Whitstable Times and Herne Bay Herald. 23 March 1878. Retrieved 13 May 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Hussey 1902, p. 44.

- ↑ Peers 1927, pp. 246–7.

- ↑ "Reculver excavations. Interesting recent discoveries". Dover Express. 10 June 1927. Retrieved 8 May 2014 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 Peers 1927, p. 247.

- ↑ Peers 1927, p. 249.

- ↑ Wilmott 2012, p. 24.

- ↑ Peers 1927, p. 245; Jessup 1936, p. 181.

- ↑ Philp 2005, p. 54.

- ↑ Duncombe 1784, p. 84 & Plate 4.

- ↑ Kelly 2008, p. 70.

- ↑ Peers 1927, pp. 247–8.

- ↑ Pridden 1787, p. 170 & Plate X, figs. 1 & 6; Kelly 2008, p. 70.

- ↑ Pridden 1787, p. 165(note) & Plate X, fig. 1; Kelly 2008, p. 70; Pridden 1809.

- ↑ Gough 1983, p. 135; Kelly 2008, pp. 67, 70; Exploring Kent's Past (n.d.). "Chapel of St James, Reculver". Kent County Council. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Peers 1927, p. 248.

- 1 2 3 Culture and Heritage (n.d.). "St John's Anglican Cathedral". NSW Government Environment & Heritage. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ State Library New South Wales (2007). "Buildings erected under Macquarie, 1817–1840s [Album view]". New South Wales Government. Items 1–3. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ↑ Culture and Heritage (n.d.). "St John's Anglican Cathedral". NSW Government Environment & Heritage. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 20 May 2015; Mdpclark (2009). "Reculver plaque". Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

Bibliography

- Anon. (1791), "The Sisters, an affecting history: With a perspective view of Reculver Church, in the county of Kent", Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure, 89: 97–10 4, OCLC 7676735

- Anon. (1808), "Storm and tide", The Literary Panorama, 3, cols. 1309–10, OCLC 7687961

- Anon. (1856), "Strolls on the Kentish coast II. Reculver and the Wentsum", The Gentleman's Magazine, 201: 313–8, ISSN 2043-2992

- Anon. (1999), "Early letters discovered at Reculver", Kent Archaeological Review (138): 189–90, ISSN 0023-0014

- Anon. (2011), John Rennie (1761–1821), Institution of Civil Engineers, archived from the original on 7 April 2014, retrieved 21 April 2014

- Bagshaw, S. (1847), History, Gazetteer & Directory of Kent, II, Bagshaw, OCLC 505035666

- Bede (1968) [1955], A History of the English Church and People, translated by Leo Sherley-Price, Penguin, ISBN 978-0-14-044042-3

- Blair, J. (1999), "Reculver", in Lapidge, M.; Blair, J.; Keynes, S.; Scraggs, D., The Blackwell Encyclopædia of Anglo-Saxon England, Blackwell, p. 386, ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1

- Blair, J. (2005), The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-822695-6

- Brooks, N. (1979), "England in the ninth century: The crucible of defeat", Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th series, 29: 1–20, doi:10.2307/3679110, ISSN 0080-4401

- Brooks, N. (1984), The Early History of the Church of Canterbury, Leicester University Press, ISBN 0-7185-1182-4

- C. of Kent (1810), "Mr. Urban", The Gentleman's Magazine, 80 (2): 204–5, ISSN 2043-2992

- Campbell, J. (1982), The Anglo-Saxons, Phaidon, ISBN 0 7148 2149 7

- Canterbury City Council (2008), Reculver Masterplan Report Volume 1 (PDF), canterbury.gov.uk, archived (PDF) from the original on 13 April 2014, retrieved 21 April 2014

- Cherry, B. (1981) [1976], "Ecclesiastical architecture", in Wilson, D.M., The Archaeology of Anglo-Saxon England, Cambridge University Press, pp. 151–200, ISBN 0-521-28390-6

- Clapham, A.W. (1930), English Romanesque Architecture Before the Conquest, Clarendon, OCLC 1210686

- Clinch, G. (1918), "Seal of the vicar of Reculver" (PDF), Archaeologia Cantiana, 33: 169–70, ISSN 0066-5894, archived (PDF) from the original on 8 July 2015, retrieved 8 July 2015

- Cotton, C. (1929), The Saxon Cathedral at Canterbury and the Saxon Saints Buried Therein, Manchester University Press, OCLC 4107830

- Cozens, Z. (1809), "Mr. Urban", The Gentleman's Magazine, 79: 906–8, ISSN 2043-2992

- Dodsworth, R.; Dugdale, W., eds. (1655), Monasticon Anglicanum sive Pandectae coenobiorum Benedictinorum Cluniacensium Cisterciensium Carthusianorum a primordiis ad eorum usque dissolutionem, Hodgkinsonne, OCLC 222915178

- Dowker, G. (1878), "Reculver church", Archaeologia Cantiana, 12: 248–68, ISSN 0066-5894

- Duncombe, J. (1784), "The history and antiquities of the two parishes of Reculver and Herne, in the county of Kent", in Nichols, J., Bibliotheca Topographica Britannica, 18, Nichols, pp. 65–161, OCLC 475730544

- Eales, R. (1992), "An introduction to the Kent Domesday", in Williams, A., The Kent Domesday, Alecto, pp. 1–49, ISBN 0-948459-98-0

- Earle, J., ed. (1865), Two of the Saxon Chronicles Parallel, With Supplementary Extracts from the Others, Clarendon, OCLC 10565546

- Farmer, D.H. (1992), The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-283069-4

- Flaherty, W.E. (1859), "A help towards a Kentish Monasticon" (PDF), Archaeologia Cantiana, 2: 49–64, ISSN 0066-5894, archived (PDF) from the original on 2 May 2014, retrieved 17 May 2014

- Fletcher, E. (1965), "Early Kentish churches", Medieval Archaeology, 9: 16–31, ISSN 0076-6097

- Flight, C. (2010), The Survey of Kent: Documents Relating to the Survey of the County Conducted in 1086, BAR British Series, 506, Archaeopress, ISBN 978-1-4073-0541-7, archived from the original on 14 May 2014, retrieved 17 May 2015

- Freeman, R. (1810), Regulbium: A Poem, with an Historical and Descriptive Account of the Roman Station at Reculver, in Kent, Rouse, Kirkby & Lawrence, OCLC 55555194

- Furley, R. (1874), A History of the Weald of Kent, with an Outline of the History of the County to the Present Time, 2, Part 2, Igglesden, Russell Smith, OCLC 4904490

- Garmonsway, G.N., ed. (1972), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Dent, ISBN 0-460-11624-X

- Glover, J. (1976), The Place Names of Kent, Batsford, ISBN 978-0-7134-3069-1

- Goodsall, R.H. (1970), A Third Kentish Patchwork, Stedehill, ISBN 978-0-950-01511-8

- Goodsall, R.H. (1981) [1966], A Kentish Patchwork, Rochester, ISBN 978-0-905540-70-2

- Gough, H. (1983), "A fresh look at the Reculver parish clerk's story", Archaeologia Cantiana, 99: 133–8, ISSN 0066-5894

- Gough, H. (1992), "Eadred's charter of AD 949 and the extent of the monastic estate at Reculver, Kent", in Ramsay, N.; Sparks, M.; Tatton-Brown, T., St Dunstan: His Life, Times and Cult, Boydell, pp. 89–102, ISBN 978-0-85115-301-8

- Gough, H. (1995) [1969], Blake, L.J., ed., The Parish of Reculver: A Short Historical Guide to the Parish and to the Present Church of St Mary the Virgin at Hillborough, St Mary the Virgin P.C.C.

- Gough, H. (2001), "A true tale of Reculver", Kent Archaeological Review (146): 137–8, ISSN 0023-0014

- Gough, H. (2002), "Coast erosion and Reculver", Kent Archaeological Review (149): 203–6, ISSN 0023-0014

- Gough, H. (2014), "The two names of a Reculver inn", Kent Archaeological Review (195): 186–91, ISSN 0023-0014

- Graham, R. (1944), "Sidelights on the rectors and parishioners of Reculver from the Register of Archbishop Winchelsey", Archaeologia Cantiana, 57: 1–12, ISSN 0066-5894, archived from the original on 10 February 2012, retrieved 17 May 2015

- Hardwick, C., ed. (1858), Historia Monasterii S Augustini Cantuariensis, Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans & Roberts, OCLC 1928519

- Harris, S. (2001), Richborough and Reculver, English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-85074-765-9

- Hasted, E. (1800), The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent, 9, Bristow, OCLC 367530442, archived from the original on 17 May 2015, retrieved 17 May 2015

- Haverfield, F.J.; Mortimer Wheeler, R.E. (1932), "Reculver", in Page, W., A History of the County of Kent, 3, Victoria County History, St Catherine, pp. 19–24, OCLC 907091, archived from the original on 5 June 2011, retrieved 17 May 2015

- Hearne, T. (1711), The Itinerary of John Leland the Antiquary (PDF), 6, OCLC 642395517, archived (PDF) from the original on 15 April 2012, retrieved 17 May 2015

- Henig, M. (2008), "'And did those feet in ancient times': Christian churches and pagan shrines in south-east Britain", in Rudling, D., Ritual Landscapes of Roman South-East Britain, Heritage, Oxbow, pp. 191–206, ISBN 978-1-905223-18-3

- Hussey, A. (1852), Notes on the Churches in the Counties of Kent, Sussex, and Surrey, Mentioned in Domesday Book, and Those of More Recent Date, Russell Smith, OCLC 5134070

- Hussey, A. (1902), "Visitations of the Archdeacon of Canterbury" (PDF), Archaeologia Cantiana, 25: 11–56, ISSN 0066-5894, archived from the original (PDF) on 2 May 2014, retrieved 17 May 2015

- Hussey, A. (1917), "Reculver and Hoath wills", Archaeologia Cantiana, 32: 77–141, ISSN 0066-5894, archived from the original on 28 October 2007, retrieved 17 May 2015

- Jessup, R.F. (1936), "Reculver", Antiquity, 10 (38): 179–94, doi:10.1017/S0003598X0001156X, ISSN 0003-598X

- Jones, B. (2007), Kent Hundred Rolls (PDF), Kent Archaeological Society, archived (PDF) from the original on 19 November 2012, retrieved 21 April 2014

- Jope, E.M. (1964), "The Saxon building-stone industry in southern and midland England", Medieval Archaeology, 8: 91–118, ISSN 0076-6097

- Kelly, S. (1992), "Trading privileges from eighth-century England", Early Medieval Europe, 1 (1): 3–28, doi:10.1111/j.1468-0254.1992.tb00002.x, ISSN 0963-9462

- Kelly, S. (2008), "Reculver Minster and its early charters", in Barrow, J.; Wareham, A., Myth, Rulership, Church and Charters Essays in Honour of Nicholas Brooks, Ashgate, pp. 67–82, ISBN 978-0-7546-5120-8

- Kerr, N. & M. (1982), A Guide to Anglo-Saxon Sites, Granada, ISBN 978-0-246-11775-5

- Kozodoy, R. (1986), "The Reculver cross", Archaeologia, 108: 67–94, doi:10.1017/s0261340900011711, ISSN 0261-3409

- Lambarde, W. (1596) [1576], A Perambulation of Kent: Conteining the Description, Hystorie, and Customes of that Shyre, Bollisant, OCLC 606507630

- Lapidge, M. (1999), "Hadrian (d. 709 or 710)", in Lapidge, M.; Blair, J.; Keynes, S.; Scraggs, D., The Blackwell Encyclopædia of Anglo-Saxon England, Blackwell, pp. 225–6, ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1

- Levison, W. (1946), England and the Continent in the Eighth Century, Oxford University Press, OCLC 381275

- Lewis, S. (1848), "Raydon – Redditch", A Topographical Dictionary of England, Lewis, pp. 645–52, OCLC 7705743, archived from the original on 17 May 2015, retrieved 17 May 2015

- Mot, T. (1809), "Mr. Urban", The Gentleman's Magazine, 79: 801–2, ISSN 2043-2992

- Page, W. (1926), "The Abbey of Reculver", A History of the County of Kent, 2, Victoria County History, St Catherine, pp. 141–2, OCLC 9243447, archived from the original on 4 May 2015, retrieved 17 May 2015

- Peers, C.R. (1927), "Reculver: Its Saxon church and cross", Archaeologia, 77: 241–56, doi:10.1017/s0261340900013436, ISSN 0261-3409

- Philp, B. (2005), The Excavation of the Roman Fort at Reculver, Kent, Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit, ISBN 0-947831-24-X

- Philipot, T. (1776), Villare Cantianum: Or, Kent Surveyed and Illustrated, Whittingham, OCLC 5469820

- Pridden, J. (1787), "Letter to Mr John Nichols", in Nichols, J., Bibliotheca Topographica Britannica, 45, Nichols, pp. 163–80, OCLC 728419767

- Pridden, J. (1809), "Reculver Church, N.E.", The Gentleman's Magazine, 79, Plate I, ISSN 2043-2992

- Roach Smith, C. (1850), The Antiquities of Richborough, Reculver, and Lymne, Russell Smith, OCLC 27084170

- Rollason, D.W. (1979), "The date of the parish boundary of Minster-in-Thanet (Kent)", Archaeologia Cantiana, 95: 7–17, ISSN 0066-5894

- Rollason, D.W. (1982), The Mildrith Legend: A Study in Early Medieval Hagiography in England, Leicester University Press, ISBN 0-7185-1201-4

- Stahlschmidt, J.C.L. (1887), The Church Bells of Kent: Their Inscriptions, Founders, Uses and Traditions, Stock, OCLC 12772194

- Taylor, C., ed. (1808), The Literary Panorama, 3, OCLC 7687961

- Taylor, H. M. (1968), "Reculver Reconsidered", The Archaeological Journal, 125: 291–6, doi:10.1080/00665983.1968.11078342, ISSN 0066-5983

- Ward, G. (1946), "Saxon abbots of Dover and Reculver" (PDF), Archaeologia Cantiana, 59: 19–28, ISSN 0066-5894, archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2016, retrieved 6 May 2016

- Willement, T. (1862), Historical Sketch of the Parish of Davington in the County of Kent and of the Priory there Dedicated to S. Mary Magdalene, Pickering, OCLC 867433157

- Williams, A.; Martin, G.H., eds. (2002) [1992], Domesday Book A Complete Translation, Penguin, ISBN 0-14-051535-6

- Wilmott, T. (2012), Richborough and Reculver, English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-84802-073-3

- Witney, K. P. (1982), The Kingdom of Kent, Phillimore, ISBN 978-0-85033-443-2

- Yorke, B. (1990), Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England, Seaby, ISBN 1-85264-027-8

- Yorke, B. (2003), Nunneries and the Anglo-Saxon Royal Houses, Continuum, ISBN 0-8264-6040-2

Coordinates: 51°22′46″N 1°11′59″E / 51.37955°N 1.19986°E