Quyllurit'i

Quyllurit'i (Quechua quyllur rit'i, "bright white snow"[1]) is a spiritual and religious festival held annually at the Sinakara Valley in the Cusco Region of Peru. The Catholic Church's official position is that the festival is in honor of the Lord of Quyllurit'i (Quechua: Taytacha Quyllurit'i, Spanish: Señor de Quyllurit'i). According to the Church the celebration originated in 1780, when a young native herder called Mariano Mayta befriended a mestizo boy called Manuel on the mountain Qullqipunku. Thanks to Manuel, Mariano's herd prospered, so his father sent him to buy clothes for the two boys in Cusco. Mariano took a sample of Manuel's clothes but could not find anything similar because that kind of cloth was only worn by an archbishop. Upon this discovery, the archbishop of Cusco sent a party to investigate but when they tried to grab Manuel, he became a bush with an image of Christ hanging from it. Thinking they had harmed his friend, Mariano died on the spot and was buried under a rock. An image of Christ painted over this boulder became known as the Lord of Quyllurit'i, which means Lord of Star Snow.

Contrary to the Catholic myth, the festival is known to the local descendants of the indigenous population of the Andes as a celebration of the stars. In particular the Pleiades, which disappears from view in April and reappears in June and signifies a time of transition from old to new and the upcoming harvest and New Year, which for the locals begins on the Winter Solstice. The festival, from the pre-Columbian perspective, has been celebrated for hundreds if not thousands of years.

The Quyllurit'i festival attracts a large number of peasants from the surrounding regions, divided in two moieties: Paucartambo groups Quechuas from the agricultural regions to the northwest of the sanctuary andQuispicanchis, which includes Aymaras from the pastoral regions to the southeast. Both moieties make an annual pilgrimage to the feast bringing large troupes of dancers and musicians in four main styles: ch'unchu, qulla, ukuku and machula. Besides peasant pilgrims, attendants include middle class Peruvians and foreign tourists. The festival takes place in late May or early June, to coincide with the full moon, one week before the Christian feast of Corpus Christi. It consists of a number of processions and dances in and around the Lord of Quyllurit'i shrine. The main event for the Church is carried out by ukukus who climb glaciers over Qullqipunku to bring back crosses and blocks of ice which are said to be medicinal. The main event for the indigenous non-Christian population who still celebrate their old spiritual beliefs is the rising of the sun on the Monday morning where tens of thousands kneel down to the first rays of light as the sun rises above the horizon.

Origins

There are several accounts of the origins of the Quyllurit'i festival. What follows are two accounts: one describes the pre-Columbian origins and the other is the "Catholic Church's" version as compiled by the priest of the town of Ccatca between 1928 and 1946.[2]

Pre-Columbian Origins

The Inca followed both solar and lunar cycles throughout the year. However, the cycle of the moon was of primary importance for both agricultural activities and the timing of festivals, which reflected in many cases celebrations surrounding animal husbandry, sowing seeds and harvesting of crops. Important festivals such as Quyllurit'i, perhaps the most important festival given its significance and meaning, are still celebrated on the full moon.

The Quyllurit'i festival falls in a period of time when the Pleiades constellation, or Seven Sisters, a 7-star cluster in the Taurus Constellation, disappears and reappears in the Southern Hemisphere. The star movement signals the time of the coming harvest and therefore a time of abundance. For this reason Incan astronomers cleverly named the Pleiades "Qullqa" or storehouse in their native language Runa Simi ("human's language") or Quechua as it is also called.

Metaphorically, due to the star’s disappearance from the night sky and reemergence approximately two months afterwards is a signal that our planes of existence have times of disorder and chaos, but also return to order. This outlook coincides with the recent Pachakuti or Inca Prophecy literally translated from the two words pacha and kuti (Quechua pacha "time and space", kuti "return") where pacha kuti means "return of time", "change of time" or "great change or disturbance in the social or political order".[3]

The prophecy therefore represents (according to the Glossary of Terminology of the Shamanic & Ceremonial Traditions of the Inca Medicine Lineage) a period of upheaval and cosmic transformation. An overturning of the space/time continuum that affects consciousness. A reversal of the world. A cataclysmic event separating eras in time.

In the current pacha it is said that we will set the world rightside up and return to a golden era. This era will last at least 500 years. The andino people and their native historical culture will see a resurgence and rise out of the previous period of conquest and oppression and begin to thrive and return to a period of grandeur.

The Pachakuti also speaks of the tumultuous nature of our current world, in particular the environmental destruction of the earth, transforming and returning to one of balance, harmony and sustainability. This will happen as we as a people change our way of thinking and become more conscious. Therefore, the Pachakuti is representative of the death of an old way of thinking about the world in which we live, and an elevation to a higher state of consciousness. In this way, we can describe ourselves not as who we are or were, but who we are becoming.

Post-Columbian (Catholic Church) Origins

In 1780, an Indian boy named Mariano Mayta used to watch over his father's herd on the slopes of the mountain Qullqipunku. Mistreated by his brother, he wandered into the snowfields of the mountain, where he found a mestizo boy, called Manuel. They became good friends and Manuel provided Mariano with food so that he did not have to return home to eat. When Mariano's father found out, he went looking for his son and was surprised to find his herd had increased. As a reward, he sent Mariano to Cusco to get new clothes. The boy asked permission to buy some for Manuel as his friend wore the same outfit everyday. His father agreed, so Mariano asked Manuel for a sample of his clothes to buy the same kind of material in Cusco.

Mariano could not find that type of cloth in Cusco because it was only used by the bishop of the city. He went to see the prelate, who was surprised by the request and ordered an inquiry on Manuel, directed by the priest of Ocongate, a town close to the mountain. On June 12, 1783, the commission ascended Qullqipunku with Mariano and found Manuel dressed in white and shining with a bright light. Blinded, they retreated only to come back later with a larger party. In their second try they were able to reach Manuel despite the intense light. However, on touching him, he became a tayanka bush (Baccharis odorata) with the body of an agonizing Christ hanging from it. Mariano, thinking they had harmed his friend, fell dead on the spot. He was buried under the rock where Manuel had last appeared.

The tayanka tree was sent to Spain, requested by king Charles III. As it was never returned, the Indian population of Ocongate protested, forcing the local priest to order a replica, which became known as Lord of Tayankani (Spanish: Señor de Tayakani). The rock under which Mariano was said to be buried attracted a great number of Indian devotees who lit candles before it. To give the site a Christian veil, religious authorities ordered the painting of an image of a crucified Christ on the rock. This image became known as Lord of Quyllurit'i (Spanish: Señor de Quyllurit'i). In Quechua, quyllur means star and Rit'i means snow thus, Lord of Quyllurit'i stands for Lord of Star Snow.[4]

Pilgrims

The Quyllurit'i festival gathers more than 10,000 pilgrims annually, most of them from rural communities in nearby regions.[5] Peasant attendees are grouped in two moieties: Paucartambo, which includes communities located to the northwest of the shrine in the provinces of Cusco, Calca, Paucartambo and Urubamba; and Quispicanchis, which encompasses those situated to the southeast in the provinces of Acomayo, Canas, Canchis and Quispicanchi. This geographic division also reflects social and economic distinctions as Paucartambo is an agricultural region inhabited by Quechuas whereas Quispicanchis is populated by Aymaras dedicated to animal husbandry.[6] Peasant communities from both moieties undertake an annual pilgrimage to the Quyllurit'i festival, each carrying a small image of Christ to the sanctuary.[7] These delegations include a large troupe of dancers and musicians dressed in four main styles.

- Ch'unchu

- Wearing feathered headdresses and a wood staff, ch'unchus represent the indigenous inhabitants of the Amazon Rainforest, to the north of the sanctuary.[8] There are several types of ch'unchu dancers, the most common is wayri ch'unchu, which comprises up to 70% of all Quyllurit'i dancers.[9]

- Qhapaq Qulla

- Dressed with a "waq'ullu" knitted mask, a hat, a woven sling and a llama skin, qullas represent the aymara inhabitants of the Altiplano, to the south of the sanctuary.[10] Qulla is considered a mestizo dance style whereas ch'unchu is regarded as indigenous.[11]

- Ukuku

- Clad in a dark coat and a woolen mask, ukukus represent the role of tricksters; they speak in high-pitched voices, play pranks and keep order among pilgrims.[12] In Quechua mythology, ukukus are the offspring of a woman and a bear, feared by everyone because of their supernatural strength. In these stories, the ukuku redeems itself by defeating a condenado, a cursed soul, and becoming an exemplary farmer.[13]

- Machula

- Wearing a mask, a humpback, a long coat and a walking stick, machulas represent the ñawpa machus, the mythical first inhabitants of the Andes. In a similar way to ukukus, they perform an ambivalent role in the festival, being comical as well as constabulary figures.[14]

Quyllur Rit'i also attracts visitors from outside the Paucartambo and Quispicanchis moieties. Since the 1970s, an increasing number of middle class Peruvians undertake the pilgrimage, some of them at a different date than more traditional pilgrims.[15] There has also been a rapid growth in the number of North American and European tourists, drawn by the indigenous character of the festival.[16]

Festival

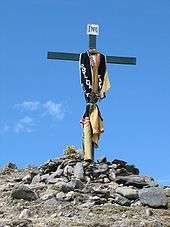

The festival is attended by many who journey to the glacier from as far away as Bolivia. However, the Christian celebration is organized by the Brotherhood of the Lord of Quyllurit'i (Spanish: Hermandad del Señor de Quyllurit'i), a lay organization which is also in charge of keeping order during the feast.[17] Preparations start on the feast of the Ascension when the Lord of Quyllurit'i is carried in procession from its chapel at Mawallani to its sanctuary at Sinakara.[18] On the first Wednesday after Pentecost, a second procession carries a statue of Our Lady of Fatima from the Sinakara sanctuary to an uphill grotto.[19] Most pilgrims arrive by Trinity Sunday when the Blessed Sacrament is taken in procession through the sanctuary; the following day the Lord of Qoyllur Rit'i is taken in procession to the grotto of the Virgin and back.[20] On the night of this second day, dance troupes take turns to perform in the shrine.[21] At dawn on the third day, ukukus grouped by moieties climb the glaciers on Qullqipunku to retrieve crosses set on top, they also bring back blocks of the ice, which is believed to have medicinal qualities.[22] They undertake this because they are considered the only ones capable of dealing with condenados, which are said to inhabit the snowfields.[23] According to oral traditions, ukukus from different moieties used to engage in ritual battles on the glaciers but this practice was banned by the Catholic Church.[24] After a mass celebrated later this day, most pilgrims leave the sanctuary except for a group which carries the Lord of Quyllurit'i in procession to Tayankani before taking it back to Mawallani.[25]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Flores Ochoa, Jorge (1990). "Taytacha Qoyllurit'i. El Cristo de la Nieve Resplandeciente". El Cuzco: resistencia y continuidad (in Spanish). Editorial Andina.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, pp. 207–209.

- ↑ Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary): pacha kuti - (Pacha: tiempo y espacio. Kuti: regreso, vuelta). Regreso del tiempo, cambio del tiempo. pacha kuti - s. Gran cambio o trastorno en el orden social o político.

- ↑ Randall, "Return of the Pleiades", p. 49.

- ↑ Dean, Inka bodies, p. 210.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, p. 217.

- ↑ Allen, The hold life has, p. 108.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, p. 222.

- ↑ Randall, "Qoyllur Rit'i", p. 46.

- ↑ Randall, "Return of the Pleiades", p. 43.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, p. 223.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, p. 218.

- ↑ Randall, "Qoyllur Rit'i", p. 43–44.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, p. 220.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Dean, Inka bodies, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, p. 215.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, p. 225.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, pp. 225–226.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, p. 226.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, p. 227.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, pp. 227–228.

- ↑ Randall, "Quyllurit'i", p. 44.

- ↑ Randall, "Return of the Pleiades", p. 45.

- ↑ Sallnow, Pilgrims of the Andes, p. 228.

Bibliography

- Allen, Catherine. The hold life has: coca and cultural identity in an Andean community. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988.

- Dean, Carolyn. Inka bodies and the body of Christ: Corpus Christi in colonial Cusco, Peru. Durham: Duke University Press, 1999.

- Randall, Robert. "Qoyllur Rit'i, an Inca fiesta of the Pleiades: reflections on time & space in the Andean world". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Etudes Andines 9 (1–2): 37–81 (1982).

- Randall, Robert. "Return of the Pleiades". Natural History 96 (6): 42–53 (June 1987).

- Sallnow, Michael. Pilgrims of the Andes: regional cults in Cusco. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quyllur Rit'i. |

- Qoyllur Riti “An Inca Festival Celebrating the Stars" by Seti Gershberg on Shamans Portal

- Qoyllur Riti “An Inca Festival Celebrating the Stars" by Seti Gershberg on The Path of the Sun

- From Ice to Icon: El Señor de Qoyllur Rit'i as symbol of native Andean Catholic worship by Adrian Locke

- Qoyllur Rit'i: In Search of the Lord of the Snow Star online exhibit by Vicente Revilla