Posterior cortical atrophy

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), also called Benson's syndrome, is a form of dementia which is usually considered an atypical variant of Alzheimer's disease.[1] The disease causes atrophy of the posterior part of the cerebral cortex, resulting in the progressive disruption of complex visual processing.[2] PCA was first described by D. Frank Benson in 1988.[3][4]

In rare cases, PCA can be caused by dementia with Lewy bodies and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease.[4][2]

PCA usually affects people at an earlier age than typical cases of Alzheimer's disease, with initial symptoms often experienced in people in their mid-fifties or early sixties.[2] This was the case with writer Terry Pratchett (1948-2015), who went public in 2007 about being diagnosed with PCA.[5] In The Mind's Eye, neurologist Oliver Sacks examines the case of concert pianist Lilian Kallir (1931–2004), who suffered from PCA.

Symptoms

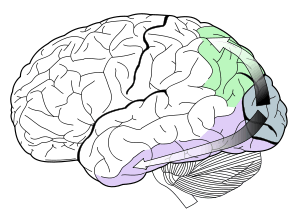

The main symptom resulting from PCA is a decrease in visuospatial and visuoperceptual capabilities.[6] Because the posterior region of the brain is home to the occipital lobe, which is responsible for visual processing, visual functions are impaired in PCA patients. The atrophy is progressive; early symptoms include difficulty reading, blurred vision, light sensitivity, issues with depth perception, and trouble navigating through space.[7][8] Additional symptoms include apraxia, a disorder of movement planning, alexia, an impaired ability to read, and visual agnosia, an object recognition disorder.[9] Damage to the ventral, or “what” stream, of the visual system, located in the temporal lobe, leads to the symptoms related to general vision and object recognition deficits; damage to the dorsal, or “where/how” stream, located in the parietal lobe, leads to PCA symptoms related to impaired movements in response to visual stimuli, such as navigation and apraxia.[9][8]

As neurodegeneration spreads, more severe symptoms emerge, including the inability to recognize familiar people and objects, trouble navigating familiar places, and sometimes visual hallucinations.[6][7] In addition, patients may experience difficulty making guiding movements towards objects, and may experience a decline in literacy skills including reading, writing, and spelling.[7][10][11] Furthermore, if neural death spreads into other anterior cortical regions, symptoms similar to Alzheimer's disease, such as memory loss, may result.[7][10] PCA patients with significant atrophy in one hemisphere of the brain may experience hemispatial neglect, the inability to see stimuli on one half of the visual field.[8] Anxiety and depression are also common in PCA patients.[12]

Diagnosis

At this time the cause of PCA is unknown; similarly, there are no fully accepted diagnostic criteria for the disease.[8] This is partially due to the gradual onset of PCA symptoms, the variety of symptoms, the rare nature of the disease and younger age of patients (initial symptoms appear in patients of 50–60 years old).[13] In 2012, the first international conference on PCA was held in Vancouver, Canada. Continued research and testing will hopefully result in accepted and standardized criteria for diagnosis.[8]

PCA patients are often initially misdiagnosed with an anxiety disorder or depression. Some believe that patients may experience depression or anxiety due to their awareness of their symptoms, such as decrease in their vision capabilities, yet they are unable to control this decline in their vision or the progressive nature of the disease. The early visual impairments of a PCA patient have often led to an incorrect referral to an ophthalmologist, which can result in unnecessary cataract surgery.[13]

Due to the lack of biological marks of PCA, neuropsychological examinations should be used for diagnosis.[14] Neuroimaging can also assist in diagnosis of PCA.[13] The common tools used for Neuroimaging of both PCA and AD patients are magnetic resonance imaging (MRI's), a popular form of medical imaging that uses magnetic fields and radio waves, as well as single-photon emission computed tomography, an imaging form that uses gamma rays, and positron emission tomography, another imaging tool that creates 3D images with a pair of gamma rays and a tracer.[15] Images of PCA patient’s brains are often compared to AD patient images to assist diagnosis. Due to the early onset of PCA in comparison to AD, images taken at the early stages of the disease will vary from brain images of AD patients. At this early stage PCA patients will show brain atrophy more centrally located in the right posterior lobe and occipital gyrus, while AD brain images show the majority of atrophy in the medial temporal cortex. This variation within the images will assist in early diagnosis of PCA; however, as the years go on the images will become increasingly similar, due to the majority of PCA patients also having AD later in life because of continued brain atrophy.[8][16] A key aspect found through brain imaging of PCA patients is a loss of grey matter (collections of neuronal cell bodies) in the posterior and occipital temporal cortices within the right hemisphere.[17]

For some PCA patients, neuroimaging may not result with a clear diagnosis; therefore, careful observation of the patient in relation to PCA symptoms can also assist in the diagnosis of the patient.[13] The variation and lack of organized clinical testing has led to continued difficulties and delays in the diagnosis of PCA in patients.[8]

Treatment

Specific and accepted scientific treatment for PCA has yet to be discovered; this may be due to the rarity and variations of the disease.[8][18] At times PCA patients are treated with prescriptions originally created for treatment of AD such as, cholinesterase inhibitors, Donepezil, Rivastigmine and Galantamine, and Memantine.[8] Antidepressant drugs have also provided some positive effects.[13]

Patients may find success with non-prescription treatments such as psychological treatments. PCA patients may find assistance in meeting with an occupational therapist or sensory team for aid in adapting to the PCA symptoms, especially for visual changes.[8][13] People with PCA and their caregivers are likely to have different needs to more typical cases of Alzheimer's disease, and may benefit from specialized support groups such as the PCA Support Group based at University College London, or other groups for young people with dementia. No study to date has been definitive to provide accepted conclusive analysis on treatment options.[13]

Connection to Alzheimer's disease

Studies have shown that PCA may be a variant of Alzheimer's disease (AD), with an emphasis on visual deficits.[9] Although in primarily different, but sometimes overlapping, brain regions, both involve progressive neural degeneration, as shown by the loss of neurons and synapses, and the presence of neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques in affected brain regions; this eventually leads to dementia in both diseases.[19][20] PCA patients have more cortical damage and gray matter (cell body) loss in posterior regions, especially in the occipital, parietal, and temporal lobes, whereas Alzheimer’s patients typically experience more damage in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.[10][19][21] PCA tends to impair working memory and anterograde memory, while leaving episodic memory intact, whereas AD patients typically have damaged episodic memory, suggesting some differences still lie in the primary areas of cortical damage.[7][19]

Over time, however, atrophy in PCA patients may spread to regions commonly damaged in AD patients, leading to common AD symptoms such as deficits in memory, language, learning, and cognition.[9][10][19][20] Although PCA has an earlier onset, many PCA patients have also been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, suggesting that the degeneration has simply migrated anteriorly to other cortical brain regions.[6][9]

There is no standard definition of PCA and no established diagnostic criteria, so it is not possible to know how many people have the condition. Some studies have found that about 5 percent of people diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease have PCA. However, because PCA often goes unrecognized, the true percentage may be as high as 15 percent. Researchers and physicians are working to establish a standard definition and diagnostic criteria for PCA. [22]

PCA may also be correlated with the diseases of Lewy body, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, Bálint's syndrome, and Gerstmann syndrome.[7][8][23] In addition, PCA may result in part from mutations in the presenilin 1 gene (PSEN1).[8]

References

- ↑ Nestor PJ, Caine D, Fryer TD, Clarke J, Hodges JR (2003). "The topography of metabolic deficits in posterior cortical atrophy (the visual variant of Alzheimer's disease) with FDG-PET". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 74: 1521–1529. doi:10.1136/jnnp.74.11.1521.

- 1 2 3 "Posterior Cortical Atrophy". UCSF Memory and Aging Center. University of California, San Francisco. Retrieved 2011-10-22.

- ↑ Benson DF, Davis RJ, Snyder BD (July 1988). "Posterior Cortical Atrophy". Archives of Neurology. 45 (7): 789–793. doi:10.1001/archneur.1988.00520310107024. PMID 3390033. Retrieved Oct 22, 2011.

- 1 2 "Posterior Cortical Atrophy". Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging. Harvard University. 2009-01-19. Retrieved 2011-10-22.

- ↑ "Terry Pratchett pledges $1 million to Alzheimer's research". Alzheimer's Research Trust. 2011-07-29.

- 1 2 3 Mendez, Mario; Mehdi Ghajarania; Kent Perryman (14 June 2002). "Posterior cortical atrophy: Clinical characteristics and differences compared to Alzheimer's disease". Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 14: 33–40. doi:10.1159/000058331.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Crutch, Sebastian; Manja Lehmann; Jonathan Schott; Gil Rabinovici; Martin Rosser; Nick Fox (February 2012). "Posterior Cortical Atrophy". The Lancet Neurology. 11: 170–178. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(11)70289-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Borruat, François-Xavier (18 October 2013). "Posterior Cortical Atrophy: Review of the Recent Literature". Neuro-Ophthalmology. 13: 406. doi:10.1007/s11910-013-0406-8. PMID 24136454.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Goenthals, Maartin; Patrick Santens (20 February 2001). "Posterior cortical atrophy. Two case reports and a review of the literature". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 103: 115–119. doi:10.1016/s0303-8467(01)00114-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Crutch SJ, Schott JM, Rabinovici GD, Boeve BF, Cappa SF, Dickerson BC, Dubois B, Graff-Radford NR, Krolak-Salmon P, Lehmann M, Mendez MF, Pijnenburg Y, Ryan NS, Scheltens P, Shakespeare T, Tang-Wai DF, van der Flier WM, Bain L, Carrillo MC, Fox NC (Jul 2013). "Shining a light on posterior cortical atrophy". Alzheimer's & Dementia. 9 (4): 463–5. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2012.11.004. PMID 23274153.

- ↑ Tsunoda, Ayami; Shuji Iritani; Norio Ozaki (17 March 2011). "Presenile dementia diagnosed as posterior cortical atrophy". Psychogeriatrics. 11: 171–176. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8301.2011.00366.x.

- ↑ Crutch, Sebastian; Manja Lehmann; Jonathan Schott; Gil Rabinovici; Martin Rosser; Nick Fox (February 2012). "Posterior cortical atrophy". The Lancet Neurology. 11: 170–178. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(11)70289-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Crutch, Sebastian J.; Manja Lehmann; Jonathan M. Schott; Gil D. Rabinovici; Martin N. Rossor; Nick C. Fox (February 2012). "Posterior Cortical Atrophy". The Lancet Neurology. 11 (2): 170–178. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(11)70289-7.

- ↑ Croisile, MD. Bernard; Alexis Brice (September 2004). "Benson's syndrome or Posterior Cortical Atrophy" (PDF). Orphanet Encyclopedia. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ Goldstein, Martin A.; Iliyan Ivanov; Michael E. Silverman (May 2011). "Posterior Cortical Atrophy: An Exemplar for Renovating Diagnostic Formulation in Neurosychiaty". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 52 (3): 326–333. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.06.013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ↑ Möller C, van der Flier WM, Versteeg A, Benedictus MR, Wattjes MP, Koedam EL, Scheltens P, Barkhof F, Vrenken H (Feb 2014). "Quantitative Regional Validation of the Visual Rating Scale for Posterior Cortical Atrophy". European Radiology. 24 (2): 397–404. doi:10.1007/s00330-013-3025-5. PMID 24092044.

- ↑ Migliaccio R, Agosta F, Toba MN, Samri D, Corlier F, de Souza LC, Chupin M, Sharman M, Gorno-Tempini ML, Dubois B, Filippi M, Bartolomeo P (November 2012). "Brain Networks in Posterior Cortical Atrophy: A Single Case Tractography Study and Literature Review". Cortex. 48 (10): 1298–1309. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2011.10.002. PMC 4813795

. PMID 22099855. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

. PMID 22099855. Retrieved 10 November 2013. - ↑ Caine, Diana (2004). "Posterior Cortical Atrophy: A Review of the Literature". Neurocase. 10 (5): 382–385. doi:10.1080/13554790490892239. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Kennedy, Jonathan; Manja Lehmann; Magdalena J. Sokolska; Hilary Archer; Elizabeth K. Warrington; Nick C. Fox; Sebastian J. Crutch (25 October 2011). "Visualizing the emergence of posterior cortical atrophy". Neurocase: The Neural Basis of Cognition. 18 (3): 248–257. doi:10.1080/13554794.2011.588180.

- 1 2 Hof, Patrick; Brent Vogt; Constantin Bouras; John Morrison (December 1997). "Atypical Form of Alzheimer's Disease with Prominent Posterior Cortical Atrophy: a Review of Lesion Distribution and Circuit Disconnection in Cortical Visual Pathways". Vision Res. 37 (24): 3609–3625. doi:10.1016/s0042-6989(96)00240-4.

- ↑ Tsunoda, Ayami; Shuji Iritani; Norio Ozaki (17 March 2011). "Presenile dementia diagnosed as posterior cortical atrophy". Psychogeriatrics. 11 (171-176): 171–176. doi:10.1111/j.1479-8301.2011.00366.x.

- ↑ "Posterior Cortical Atrophy | Signs, Symptoms, & Diagnosis". Dementia. Retrieved 2016-07-25.

- ↑ Nagaratnam, Nages; Kujan Nagaratnam; Daniel Jolley; Allan Ting (6 June 2001). "Dementia following posterior cortical atrophy—a descriptive clinical case report". Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 33: 179–190. doi:10.1016/s0167-4943(01)00179-0.