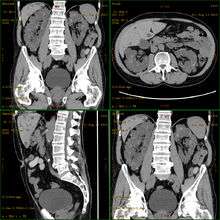

Polycystic kidney disease

| Polycystic kidney disease | |

|---|---|

| |

| Polycystic kidneys | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Nephrology |

| ICD-10 | Q61 |

| ICD-9-CM | 753.1 |

| OMIM | 173900 |

| DiseasesDB | 10262 10280 |

| MedlinePlus | 000502 |

| eMedicine | med/1862 ped/1846 radio/68 radio/69 |

| Patient UK | Polycystic kidney disease |

| MeSH | D007690 |

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD or PCKD, also known as polycystic kidney syndrome) is a genetic disorder in which abnormal cysts develop and grow in the kidneys.[1] Cystic disorders can express themselves at any point, infancy, childhood, or adulthood.[2] The disease occurs in humans and some other animals. PKD is characterized by the presence of multiple cysts (hence, "polycystic") typically in both kidneys; however, 17% of cases initially present with observable disease in one kidney, with most cases progressing to bilateral disease in adulthood.[3]

Polycystic kidney disease is one of the most common hereditary diseases in the United States, affecting more than 600,000 people. It is the cause of nearly 10% of end-stage renal disease and affects men, women, and all races equally.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms include high blood pressure, headaches, abdominal pain, blood in the urine, and excessive urination.[5] Other symptoms include pain in the back, and cyst formation (renal and other organs).[6]

Cause

Polycystic kidney disease is a general term for the two types of PKD, each having their own pathology and causes. The two types of PKD are autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD), which differ in their mode of genetic inheritance.[7][8]

Autosomal dominant

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common of all the inherited cystic kidney diseases[3][9][10] with an incidence of 1:500 live births.[3][10] Studies show that 10% of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) patients being treated with dialysis in Europe and the U.S. were initially diagnosed and treated for ADPKD.[3][8]

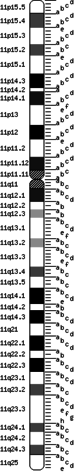

There are three genetic mutations in the PKD-1, PKD-2, and PKD3 gene with similar phenotypical presentations. Gene PKD1 is located on chromosome 16 and codes for a protein involved in regulation of cell cycle and intracellular calcium transport in epithelial cells, and is responsible for 85% of the cases of ADPKD. A group of voltage-linked calcium channels are coded for by PKD2 on chromosome 4. PKD3 recently appeared in research papers as a postulated third gene.[3][9] Fewer than 10% of cases of ADPKD appear in non-ADPKD families. Cyst formation begins in utero from any point along the nephron, although fewer than 5% of nephrons are thought to be involved. As the cysts accumulate fluid, they enlarge, separate entirely from the nephron, compress the neighboring kidney parenchyma, and progressively compromise kidney function.[8]

Autosomal recessive

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) (OMIM #263200) is the lesser common of the two types of PKD, with an incidence of 1:20,000 live births and is typically identified in the first few weeks after birth. Unfortunately, the kidneys are often underdeveloped resulting in a 30% death rate in newborns with ARPKD.[3][8]

Mechanism

Some indications are that both autosomal and recessive polycystic kidney disease cyst formation is tied to cilia-mediated signaling that is irregular. Further, the polycystin-1 and polycystin-2 proteins appear to be involved in both autosomal and recessive polycystic kidney disease due to defects in both proteins.[11] Both proteins have communication with calcium channel proteins this causes reduction in resting (intracellular) calcium and endoplasmic reticulum storage of calcium.[12] The disease is characterized by a ‘second hit’ phenomenon, in which a mutated dominant allele is inherited from a parent, with cyst formation occurring only after the normal, wild-type gene sustains a second genetic ‘hit’, resulting in renal tubular cyst formation and disease progression.[13] Specifically, PKD is thought to result from defects in the primary cilium, an immotile, hair-like cellular organelle present on the surface of most cells in the body, anchored in the cell body by the basal body.[13] In the kidney, primary cilia have been found to be present on most cells of the nephron, projecting from the apical surface of the renal epithelium into the tubule lumen. In response to fluid flow over the renal epithelium, the primary cilium is bent, resulting in a flow-induced increase in intracellular calcium.While it is not known how defects in the primary cilium lead to cyst development, it is thought to possibly be related to disruption of one of the many signaling pathways regulated by the primary cilium, including intracellular calcium, Hedgehog, Wnt/β-catenin, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), or planar cell polarity (PCP).function of the primary cilium is impaired, resulting in disruption of a number of intracellular signaling cascades that produce dedifferentiation of cystic epithelium, increased cell division, increased apoptosis, and loss of resorptive capacity.[8][13]

Prognosis

ADPKD individuals might have a normal life; conversely, ARPKD can cause kidney dysfunction and can lead to kidney failure by the age of 40-60. ADPKD1 and ADPKD2 are very different, in that ADPKD2 is much milder.[14] Currently, there are no therapies proven effective to prevent the progression polycystic kidney disease (autosomal dominant).[15]

Treatment and research

There is no FDA-approved treatment. However, it has been shown that mild to moderate dietary restrictions slow the progression of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD).[16] If and when the disease progresses enough in a given case, the nephrologist or other practitioner and the patient will have to decide what form of renal replacement therapy will be used to treat end-stage kidney disease (kidney failure, typically stage 4 or 5 of chronic kidney disease).[17]

That will either be some form of dialysis, which can be done at least two different ways at varying frequencies and durations (whether it is done at home or in the clinic depends on the method used and the patient's stability and training) and eventually, if they are eligible because of the nature and severity of their condition and if a suitable match can be found, unilateral or bilateral kidney transplantation.[17]

A Cochrane Review study of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease made note of the fact that it is important at all times, while avoiding antibiotic resistance, of course, to control infections of the cysts in the kidneys, and if affected, the liver, when needed for a certain duration to combat infection, by using, quote: "bacteriostatic and bacteriocidal drugs". Lastly, the study also noted that the direction of research, quote: "has been focused on the genetics and pathophysiology of ADPKD and on promising therapies aimed at cyst initiation or expansion.".[8][17]

See also

References

- ↑ "polycystic kidney disease" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Cramer, Monica T.; Guay-Woodford – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.), Lisa M. (2015-07-01). "Cystic Kidney Disease: A Primer". Advances in Chronic Kidney Disease. 22 (4): 297–305. doi:10.1053/j.ackd.2015.04.001. ISSN 1548-5609. PMID 26088074.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bisceglia M, Galliani CA, Senger C, Stallone C, Sessa A (2006). "Renal cystic diseases: a review". Advanced Anatomic Pathology. 13 (13): 26–56. doi:10.1097/01.pap.0000201831.77472.d3. PMID 16462154.

- ↑ Tamparo, Carol (2011). Fifth Edition : Diseases of the Human Body. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Company. p. 443. ISBN 978-0-8036-2505-1.

- ↑ "Polycystic kidney disease". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2015-07-30.

- ↑ "Polycystic Kidney Disease". www.niddk.nih.gov. Retrieved 2015-07-31.

- ↑ Porth, Carol (2011-01-01). Essentials of Pathophysiology: Concepts of Altered Health States. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781582557243.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Phua, YL; Ho, J (April 2015). "MicroRNAs in the pathogenesis of cystic kidney disease.". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 27 (2): 219–26. doi:10.1097/mop.0000000000000168. PMID 25490692.

- 1 2 Torres VE; Harris PC; Pirson Y (2007). "Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease". Lancet. 369 (9569): 1287–301. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60601-1. PMID 17434405.

- 1 2 Simons M; Walz G (2006). "Polycystic kidney disease: cell division with a c(l)ue?". Kidney International. 70 (5): 854–864. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5001534. PMID 16816842.

- ↑ Halvorson, Christian R; Bremmer, Matthew S; Jacobs, Stephen C (2010-06-24). "Polycystic kidney disease: inheritance, pathophysiology, prognosis, and treatment". International Journal of Nephrology and Renovascular Disease. 3: 69–83. ISSN 1178-7058. PMC 3108786

. PMID 21694932.

. PMID 21694932. - ↑ Johnson, Richard J.; Feehally, John; Floege, Jurgen (2014-09-05). Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology: Expert Consult - Online. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323242875.

- 1 2 3 Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology: Polycystic Kidney Disease: Inheritance, pathophysiology, prognosis, and treatment - Online. Int J nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014-05-24. ISBN 9780323242875.

- ↑ "Polycystic Kidney Disease: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology".

- ↑ "Which therapies are the most effective to prevent the progression of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease? | Cochrane". www.cochrane.org. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- ↑ Warner, Gina; Hein, Kyaw Zaw; Nin, Veronica; Edwards, Marika; Chini, Claudia C. S.; Hopp, Katharina; Harris, Peter C.; Torres, Vicente E.; Chini, Eduardo N. (2015-11-04). "Food Restriction Ameliorates the Development of Polycystic Kidney Disease". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN. doi:10.1681/ASN.2015020132. ISSN 1533-3450. PMID 26538633.

- 1 2 3 Montero, Nuria; Sans, Laia; Webster, Angela C; Pascual, Julio (29 January 2014). "Interventions for infected cysts in people with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010946/full. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

Further reading

- Chapin, Hannah C.; Caplan, Michael J. (2010-11-15). "The cell biology of polycystic kidney disease". The Journal of Cell Biology. 191 (4): 701–710. doi:10.1083/jcb.201006173. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 2983067

. PMID 21079243.

. PMID 21079243. - Harris, Peter C.; Torres, Vicente E. (2009-01-01). "Polycystic Kidney Disease". Annual Review of Medicine. 60: 321–337. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.60.101707.125712. ISSN 0066-4219. PMC 2834200

. PMID 18947299.

. PMID 18947299. - Press, Dove. "Polycystic kidney disease: inheritance, pathophysiology, prognosis, an | IJNRD". www.dovepress.com. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

External links

- Polycystic Kidney Disease Research and Education

- The National Kidney Foundation: A to Z Health Guide

- Enfermedad Polquística Renal en castellano (Spanish Wikipedia)