Polynya

A polynya /pəˈlɪnjə/ is an area of open water surrounded by sea ice.[1] It is now used as geographical term for an area of unfrozen sea within the ice pack. It is a loanword from Russian: полынья (polynya) Russian pronunciation: [pəlɨˈnʲja], which refers to a natural ice hole, and was adopted in the 19th century by polar explorers to describe navigable portions of the sea.[2][3] In past decades, for example, some polynyas, such as the Weddell Polynya, have lasted over multiple winters (1974–1976).[4]

Formation

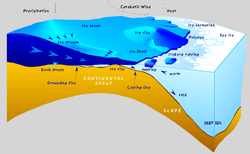

Polynyas are formed through two main processes:

- Sensible heat polynya: this is thermodynamically driven, and typically occurs when warm water upwelling keeps the surface water temperature at or above the freezing point. This reduces ice production and may stop it altogether.

- Latent heat polynya: is formed through the action of katabatic wind or ocean currents which act to drive ice away from a fixed boundary, such as a coastline, fast ice, or an ice bridge. The polynya forms initially by the first year pack ice being driven away from the coast, which leaves an area of open water within which new ice is formed. This new ice is then also herded downwind toward the first year pack ice. When it reaches the pack ice the new ice is consolidated onto the pack ice. The latent heat polynya is the open water region between the coast and the ice pack.

Latent heat polynyas are regions of high ice production and therefore are possible sites of dense water production in both polar regions. The high ice production rates within these polynyas leads to a large amount of brine rejection into the surface waters. This salty water then sinks and mixes to possibly form new water masses. It is an open question as to whether the polynyas of the Arctic can produce enough dense water to form a major portion of the dense water required to drive the thermohaline circulation.

Ecology

Some polynyas, such as the North Water Polynya between Canada and Greenland occur seasonally at the same time and place each year. Because animals can adapt their life strategies to this regularity, these types of polynyas are of special ecological research significance. In winter, marine mammals such as walruses, narwhals and belugas that do not migrate south, remain there. In spring, the thin or absent ice cover allows light in, through the surface layer as soon as the winter night ends, which triggers the early blooming of microalgae that are at the basis of the marine food chain. So, polynyas are suspected to be places where intense and early production of the planktonic herbivores ensure the transfer of solar energy (food chain) fixed by planktonic microalgae to Arctic cod, seals, whales, and polar bears. Polar bears are known to be able to swim as far as 65 kilometres across open waters of a polynya.[5]

The presence of polynyas in McMurdo Sound in the Antarctic provides an ice-free area where penguins can feed, so is important for the survival of the Cape Royds penguin colony.[6]

Arctic navigation

When submarines of the U.S. Navy made expeditions to the North Pole in the 1950s and 60s, there was a significant concern about surfacing through the thick pack ice of the Arctic Ocean. In 1962, both the USS Skate and USS Seadragon surfaced within the same, large polynya near the North Pole, for the first polar rendezvous of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet and the U.S. Pacific Fleet.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ W.J. Stringer and J.E. Groves. 1991. Extent of Polynyas in the Bering and Chukchi Seas

- ↑ Sherard Osborn, Peter Wells and A. Petermann. 1866. Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London, Vol 12 no 2 1867–1868 pp 92–113 On the Exploration of the North Polar Region

- ↑ polynya, Merriam Webster Dictionary

- ↑ Weddell Polynya, NASA, 1999

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan. 2008 Polar Bear: Ursus maritimus, Globaltwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg

- ↑ "Penguins in high latitudes". NZETC. 12 June 2014.

- ↑ Tales of a Cold War Submariner by Dan Summitt, 2004.