Salients, re-entrants and pockets

.svg.png)

A salient is a battlefield feature that projects into enemy territory. The salient is surrounded by the enemy on three sides, making the troops occupying the salient vulnerable. The enemy's line facing a salient is referred to as a re-entrant (an angle pointing inwards). A deep salient is vulnerable to being "pinched out" across the base, forming a pocket in which the defenders of the salient become isolated. On the other hand, a breakout from the salient's tip can threaten the defender's rear areas and leaves neighbouring sections of their line open to attack from behind.

Salient

Salients can be formed in a number of ways. An attacker can produce a salient in the defender's line by either intentionally making a pincer movement around the flanks of a strongpoint, which becomes the tip of the salient, or by making a broad, frontal attack which is held up in the centre but advances on the flanks. An attacker would usually produce a salient in his own line by making a broad, frontal attack that is successful only in the centre, which becomes the tip of the salient.

In trench warfare, salients are distinctly defined by the opposing lines of trenches, and they were commonly formed by the failure of a broad frontal attack. The static nature of the trenches meant that forming a pocket was difficult, but the vulnerable nature of salients meant that they were often the focus of attrition battles.

Examples

- On the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, during the American Civil War, Union General Daniel Sickles moved his III Corps ahead of the main line of the Union army without orders, causing him to be nearly cut off from the main army when the Confederates attacked. Sickles had held a similar position at Catherine's Furnace in the Battle of Chancellorsville two months earlier, and in both cases his corps was badly mauled and had to be rescued by other units.

- At the Battle of Spotsylvania during the American Civil War, Confederate forces arrived first at a strategic crossroads, and constructed a timber-reinforced line of trenches to stand against the numerically superior Union army. The trench line bulged forward to protect a piece of high ground, in a curve that became known as the Mule Shoe Salient. Union troops concentrated their attack on this point, broke through, and 22 hours of brutal, hand-to-hand fighting ensued before the Confederates pulled back to a new position.

- In World War I, the British occupied a large salient at Ypres for most of the war. Formed as a result of the First Battle of Ypres, it became one of the most bloody sectors of the Western Front. So enduring was the feature and so dreadful its reputation that when British infantry spoke of "The Salient", it was understood that they were referring to Ypres.[1]

- A similar salient existed around the French city of Verdun; the Battle of Verdun around it cost both sides heavy casualties.

- Also in World War I, the Germans occupied a small salient in front of Fromelles called the Sugarloaf due to its distinctive shape. Being small, it provided advantage to the occupiers by allowing them to enfilade the stretches of no man's land on either flank.

- In World War II, the Soviet Union occupied a massive, 150 km deep salient at Kursk that became the site of the largest tank battle in history and a decisive battle on the Eastern Front.

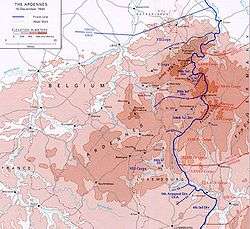

- Also in World War II, the German Army launched a surprise attack against advancing Allied forces in the Ardennes (a region of extensive forests primarily in Belgium and Luxembourg) in December 1944. This battle created a large salient for several weeks, and is commonly known as the Battle of the Bulge (also known as the Ardennes Offensive and the Von Rundstedt Offensive).

- During the Turkish military intervention on the island of Cyprus in 1974, Turkish Forces reached as far south as the Turkish Cypriot village of Louroujina. The cease-fire line dividing Cyprus into Greek and Turkish-controlled sectors put Louroujina in a salient — accessible from the rest of Turkish Cypriot-controlled Cyprus by a single road.

In mobile warfare, such as the German Blitzkrieg, salients were more likely to be made into pockets which became the focus of annihilation battles.

A pocket carries connotations that the encircled forces have not allowed themselves to be encircled intentionally, as they may, when defending a fortified position which is usually called a siege. This is a similar distinction to that made between a skirmish and pitched battle.

Soviet military doctrine

Soviet military doctrine distinguishes several sizes of encirclement:

- Cauldron or kettle (Rus. котёл, kotyol or kotel): a very large, strategic-level concentration of trapped enemy forces

- Sack (мешок, meshok): an operational-level trapped enemy force

- Nest (гнездо, gnezdo): a tactical-level trapped enemy force

The significances of these terms are reflected by the conception of what can be expected in combat in encirclement operations. A cauldron is expected to be “boiling” with combat activity, the large enemy forces still quite able to offer “hot” resistance in the initial stages of encirclement, and so are to be contained, but not engaged directly. A sack in Soviet experience was often created as a result of operational breakthroughs, and was sometimes as unexpected for the Soviet command as for the enemy. This encirclement, sometimes of an entity of unknown size, tended to move for some time after the initial encirclement due to inherently dynamic nature of operational warfare. By contrast a nest was a reference to a tactical, well-defined and contained encirclement of enemy troops that was seen as a fragile construct of enemy troops unsupported by its parent formation (the use of the word nest, is similar to the more familiar English expression machine gun nest).

Notable pockets

In World War II

- During Operation Barbarossa, almost the entire Soviet Western Front was encircled and destroyed by the Germans in the Battle of Bialystok-Minsk.

- Later, 230,000 Soviet troops were captured in a pocket at Smolensk when isolated by the Panzer forces of General Heinz Guderian on July 20, 1941.

- German and Romanian forces encircled and captured thousands of Soviet troops in the Siege of Odessa.

- At the end of Operation Barbarossa, most of the Soviet Southwestern Front (about 450,000 soldiers) was encircled in the First Battle of Kiev.

- In the winter of 1942, thousands of German troops were encircled in the Demyansk Pocket in northwestern Russia, but were relieved the following spring.

- In the winter of 1942, 5,500 German troops were encircled by the Soviets in the Kholm Pocket.

- In the spring of 1942, thousands of Soviet troops engaged in an offensive thrust were encircled during the German counterattack in the Second Battle of Kharkov.

- In November 1942, during the Battle of Stalingrad, nearly all of the German Sixth Army was encircled and destroyed in Operation Uranus. The Italian Army in Russia and Second Army (Hungary) were similarly eliminated during Operation Little Saturn.

- In May 1944, nearly half the German and Romanian garrison in modern Crimea were captured during the Crimean Offensive, primarily in Sevastopol.

- In June and July 1944, over 500,000 German troops were killed or captured during Operation Bagration in modern Belarus.

- In August 1944, over 800,000 German and Romanian troops were overrun in the second Jassy-Kishinev Offensive in modern Romania.

- In September 1944, following the D-Day landings, the German Seventh Army was trapped in the Falaise pocket.

- In 1944, thousands of Germans troops were encircled by a mostly Canadian force in the Breskens Pocket during the Battle of the Scheldt.

- In winter of 1944-1945, a large number of German troops was isolated in the Courland Pocket in northwestern Latvia until the end of the war.

- Also during the winter of 1944-1945, nearly 300,000 German troops were overrun in the Vistula-Oder Offensive in modern Poland.

- In 1944-1945, 180,000 German and Hungarian troops were isolated by Soviet troops in the Siege of Budapest.

- In 1945, 325,000 German troops were isolated and captured by advancing American armies in the Ruhr pocket.

- In April and May 1945, over 750,000 German troops were encircled and destroyed in the Battle of Berlin and collapse of the Third Reich.

- Finally in August 1945, over 400,000 Japanese and Manchurian troops were encircled over a broad area during the Soviet invasion of Manchuria.

Other pockets

- The Hornet's Nest at the Battle of Shiloh in the US Civil War, where two Union divisions were surrounded, cut off from the rest of the army, and held out against ferocious Confederate attacks for six hours before surrendering.

- Campo Vía in the Chaco War.

- In the Yugoslav wars the Medak Pocket was a Serb-populated area in Croatia that was invaded by Croatians in September 1993.

- In the war in Donbass, Ukrainian troops were encircled at Ilovaisk in August 2014, suffering heavy material and human losses.

Cerco

In Spanish the word Cerco (literally a fence or siege) is commonly used to refer to an encircling military force. Cercos were particularly common in the Chaco War between Bolivia and Paraguay (1932-1935) and encirclement battles were decisive for the outcome of the war. In the Campo Vía pocket 7,500 Bolivians were taken prisoner out of an initial combat force of 10,000. Other cercos of the war include the battle of Campo Grande and the battle of Cañada Strongest.

Kessel

In German the word Kessel (literally a cauldron) is commonly used to refer to an encircled military force, and a Kesselschlacht (cauldron battle) refers to a pincer movement. The common tactic which would leave a Kessel is referred to Keil and Kessel (Keil means wedge). The term is sometimes borrowed for use in English texts about World War II. Another use of Kessel is to refer to Kessel fever, the panic and hopelessness felt by any troops who were surrounded with little or no chance of escape. Examples of Kessel battles are:

- Demyansk Pocket, 1942

- Battle of Stalingrad, 1942–43

- Velikiye Luki Pocket 1942-1943

- Second Battle of Kharkov, 1943

- Korsun Pocket, 1944

- Kamenets-Podolsky pocket 1944 (aka Hube's Pocket)

- Siege of Memel, 1945

- Battle of Halbe, 1945

- Battle of Berlin, 1945

Also, during the Battle of Arnhem, the Germans referred to the pocket of trapped British Paratroops as the Hexenkessel (lit. The Witches' Cauldron).

Motti

Motti is Finnish military slang for a totally encircled enemy unit. The tactic of encircling it is called motitus, literally meaning the formation of an isolated block or "motti", but in effect meaning an entrapment or envelopment.

The word motti is borrowed from the Swedish mått, or "measure" which means one cubic meter of firewood or pulpwood. When collecting timber for these purposes, the logs were cut and stacked in 1 m³ cubical stacks, each one a "motti", which would be left scattered in the woods to be picked up later. The word also means "mug" in many Finnish dialects; motti is thus related to kessel. A motti in military tactics therefore means the formation of "bite sized" enemy units which are easier to contain and deal with.

This tactic of envelopment was used extensively by the Finnish forces in the Winter War and the Continuation War to good effect. It was especially effective against some of the mechanized units of the Soviet Army, which were effectively restricted to the long and narrow forest roads with virtually no way other than forwards or backwards. Once committed to a road, the Soviet troops effectively were trapped. Unlike the mechanized units of the Soviets, the Finnish troops could move quickly through the forests on skis and break columns of armoured Soviet units into smaller chunks (e.g., by felling trees along the road). Once the large column was split up into smaller armoured units, the Finnish forces attacking from within the forest could strike the weakened column. The smaller pockets of enemy troops could then be dealt with individually by concentrating forces on all sides against the entrapped unit.

A motitus is therefore a double envelopment manoeuvre, using the ability of light troops to travel over rough ground to encircle enemy troops on a road. Heavily outnumbered but mobile forces could easily immobilize an enemy many times more numerous.

By cutting the enemy columns or units into smaller groups and then encircling them with light and mobile forces, such as ski-troops during winter a smaller force can overwhelm a much larger force. If the encircled enemy unit was too strong, or if attacking it would have entailed an unacceptably high cost, e.g., because of a lack of heavy equipment, the motti was usually left to "stew" until it ran out of food, fuel, supplies, and ammunition and was weakened enough to be eliminated. Some of the larger mottis held out until the end of the war because they were resupplied by air. Being trapped, these units were therefore not available for battle operations.

The largest motti battles in the Winter War occurred at the Battle of Suomussalmi. Three Finnish regiments enveloped and destroyed two Soviet divisions as well as a tank brigade trapped on a road.

See also

References

- ↑ C. A. Rose (June 2007). Three Years in France with the Guns: Being Episodes in the Life of a Field Battery. Echo Library. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-4068-4042-1. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

External links

| Look up salient, re-entrant, or pocket in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- The Great Kitilä Motti (Winter War history from a documentary film's website)