Banff Springs snail

| Banff Springs snail | |

|---|---|

| |

| Physella johnsoni | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| (unranked): | clade Heterobranchia clade Euthyneura clade Panpulmonata clade Hygrophila |

| Superfamily: | Planorboidea |

| Family: | Physidae |

| Subfamily: | Physinae |

| Tribe: | Physellini |

| Genus: | Physella |

| Species: | P. johnsoni |

| Binomial name | |

| Physella johnsoni (Clench, 1926) | |

The Banff Springs snail (Physella johnsoni) is a species of small air-breathing freshwater snail in the family Physidae.

Based on molecular research, it appears that Physella johnsoni separated out as a species from Physella gyrina about 10,000 years ago.[2]

Description, habitat and distribution

These aquatic pulmonate gastropod mollusks are approximately the size of unpopped corn kernels. The largest ones are only about one centimetre long, and like all of the Physidae, the shells are sinistral or coiled left-handed. The snails' diet consists of periphyton.

The Banff Springs snail was first identified in 1926 in the nine sulphurous hot springs of Sulphur Mountain in Banff National Park, Alberta, Canada, and has been found nowhere else. It is very unusual because it is adapted to life in thermal springs where the water is low in oxygen and high in hydrogen sulfide, an environment too harsh for most animals to survive in. Since its discovery, its range has shrunk to just five of the nine hot springs.

Conservation

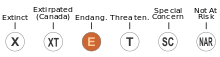

The reduction in Banff Spring snail population and range is likely attributable to human use of the hot springs, although fluctuating water temperature is also a factor. In April 1997 it became the first living mollusc to be placed on Canada's national list of species at risk. In 2000 it was classified as endangered by COSEWIC and the Canadian Species at Risk Act listed it in the List of Wildlife Species at Risk as being endangered in Canada.[1]

Parks Canada is trying to protect the species through education, law enforcement, facility closure and scientific research. In 1996 Parks Canada started a research and recovery program for the snail including the closure of the swimming pool at the Cave and Basin National Historic Site. The goals of the program are to maintain self-sustaining populations of the snail, re-establish populations at all historic locations, and hopefully to downlist the species' status.

The snail population fluctuates seasonally. During times when the numbers are critically low, the snail is most vulnerable to human disturbances or natural disasters (like the spring temporarily drying up). While scientists do not know exactly why the population fluctuates so much, it is probably due to changes in water temperature and chemistry or changes to the bacteria and algae. It is estimated that the population varies between 1,500 and 15,000 snails. At its lowest points, the entire population of snails can fit in an ice cream cone, and at its highest, in a one-litre milk carton.

Conservation biologist Dwayne Lepitzki believes that the leading cause of the thermal springs drying up and the decline in snail population is climate change. Until 1996, the only recorded instance of any Sulphur Mountain thermal spring drying up was the Upper Hot Spring in 1923, and now it's a regular occurrence.[3]

Every four weeks researchers and volunteers count the snails and analyse the water chemistry. There is also a captive breeding program being performed, and if it is successful, the snails will be introduced back to the two additional springs where the species was historically present. Eggs are currently hatching in captivity; the time from laying to hatching is four to eight days.

Snails were no longer present at Upper Hot, Upper Middle, Kidney, and Vermilion Cool springs[4] and are now present at Upper middle and Kidney due to Parks Canada's Recovery actions in 2002 for the Upper Middle and 2003 for the Kidney spring.[5] The snails are most populated at the Cave and Basin National Historic Site.

See also

References

- 1 2 COSEWIC. 2005. Canadian Species at Risk. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 64 pp., page 13.

- ↑ Remigio, E.A.; Lepitzki, D.A.; Lee, J.S.; Hebert, P.D. (2001). "Molecular systematic relationships and evidence for a recent origin of the thermal spring endemic snails Physella johnsoni and Physella wrighti (Pulmonata: Physidae)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 79 (11): 1941–1950. doi:10.1139/cjz-79-11-1941.

- ↑ http://www.keenforgreen.com/b/banff-springs-snails-suffer-because-climate-change

- ↑ "Species Profile: Banff Springs Snail". Species at Risk Public Registry. 2009-05-13.

- ↑ http://www.pc.gc.ca/nature/eep-sar/itm3/eep-sar3a/4.aspx