Perpetual calendar

A perpetual calendar is a calendar valid for many years, usually designed to allow the calculation of the day of the week for a given date in the future.

For the Gregorian and Julian calendars, a perpetual calendar typically consists of one of two general variations:

- 14 one-year calendars, plus a table to show which one-year calendar is to be used for any given year. These one-year calendars divide evenly into two sets of seven calendars: seven for each common year (year that does not have a February 29) that starts on each day of the week, and seven for each leap year that starts on each day of the week, totaling fourteen. (See Dominical letter for one common naming scheme for the 14 calendars.)

- Seven (31-day) one-month calendars (or seven each of 28–31 day month lengths, for a total of 28) and one or more tables to show which calendar is used for any given month. Some perpetual calendars' tables slide against each other, so that aligning two scales with one another reveals the specific month calendar via a pointer or window mechanism.[1]

The seven calendars may be combined into one, either with 13 columns of which only seven are revealed,[2][3] or with movable day-of-week names (as shown in the pocket perpetual calendar picture.

Note that such a perpetual calendar fails to indicate the dates of moveable feasts such as Easter, which are calculated based on a combination of events in the Tropical year and lunar cycles. These issues are dealt with in great detail in Computus.

An early example of a perpetual calendar for practical use is found in the manuscript GNM 3227a. The calendar covers the period of 1390–1495 (on which grounds the manuscript is dated to c. 1389). For each year of this period, it lists the number of weeks between Christmas day and Quinquagesima. This is the first known instance of a tabular form of perpetual calendar allowing the calculation of the moveable feasts which became popular during the 15th century.[4]

Other uses of the term "perpetual calendar"

- Offices and retail establishments often display devices containing a set of elements to form all possible numbers from 1 through 31, as well as the names/abbreviations for the months and the days of the week, so as to show the current date for the convenience of people who might be signing and dating documents such as checks. Establishments that serve alcoholic beverages may use a variant that shows the current month and day, but subtracting the legal age of alcohol consumption in years, indicating the latest legal birth date for alcohol purchases.

- Certain calendar reforms have been labeled perpetual calendars because their dates are fixed on the same weekdays every year. Examples are The World Calendar, the International Fixed Calendar and the Pax Calendar. Technically, these are perennial calendars. Their purpose, in part, is to eliminate the need for perpetual calendar tables, algorithms and computation devices.

- In watchmaking, "perpetual calendar" describes a calendar mechanism that correctly displays the date on the watch 'perpetually', taking into account the different lengths of the months as well as leap days. The internal mechanism will move the dial to the next day.[5]

These meanings are beyond the scope of the remainder of this article.

Algorithms

Perpetual calendars use algorithms to compute the day of the week for any given year, month, and day of month. Even though the individual operations in the formulas can be very efficiently implemented in software, they are too complicated for most people to perform all of the arithmetic mentally.[6] Perpetual calendar designers hide the complexity in tables to simplify their use.

A perpetual calendar employs a table for finding which of fourteen yearly calendars to use. A table for the Gregorian calendar expresses its 400-year grand cycle: 303 common years and 97 leap years total to 146,097 days, or exactly 20,871 weeks. This cycle breaks down into one 100-year period with 25 leap years, making 36,525 days, or one day less than 5,218 full weeks; and three 100-year periods with 24 leap years each, making 36,524 days, or two days less than 5,218 full weeks.

Within each 100-year block, the cyclic nature of the Gregorian calendar proceeds in exactly the same fashion as its Julian predecessor: A common year begins and ends on the same day of the week, so the following year will begin on the next successive day of the week. A leap year has one more day, so the year following a leap year begins on the second day of the week after the leap year began. Every four years, the starting weekday advances five days, so over a 28-year period it advances 35, returning to the same place in both the leap year progression and the starting weekday. This cycle completes three times in 84 years, leaving 16 years in the fourth, incomplete cycle of the century.

A major complicating factor in constructing a perpetual calendar algorithm is the peculiar and variable length of February, which was at one time the last month of the year, leaving the first 11 months March through January with a five-month repeating pattern: 31, 30, 31, 30, 31, ..., so that the offset from March of the starting day of the week for any month could be easily determined. Zeller's congruence, a well-known algorithm for finding the day of week for any date, explicitly defines January and February as the "13th" and "14th" months of the previous year in order to take advantage of this regularity, but the month-dependent calculation is still very complicated for mental arithmetic:

Instead, a table-based perpetual calendar provides a simple look-up mechanism to find offset for the day of week for the first day of each month. To simplify the table, in a leap year January and February must either be treated as a separate year or have extra entries in the month table:

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Add | 0 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 5 |

| For leap years | 6 | 2 |

Perpetual Julian and Gregorian calendar table

For Julian dates before 1300 and after 1999 the year in the table which differs by an exact multiple of 700 years should be used. For Gregorian dates after 2299, the year in the table which differs by an exact multiple of 400 years should be used. The values "r0" through "r6" indicate the remainder when the Hundreds value is divided by 7 and 4 respectively, indicating how the series extend in either direction. Both Julian and Gregorian values are shown 1500–1999 for convenience.

For each component of the date (the hundreds, remaining digits and month), the corresponding numbers in the far right hand column on the same line are added to each other and the day of the month. This total is then divided by 7 and the remainder from this division located in the far right hand column. The day of the week is beside it. Bold figures (e.g., 04) denote leap year. If a year ends in 00 and its hundreds are in bold it is a leap year. Thus 19 indicates that 1900 is not a Gregorian leap year, (but 19 in the Julian column indicates that it is a Julian leap year, as are all Julian x00 years). 20 indicates that 2000 is a leap year. Use Jan and Feb only in leap years.

| 100s of Years | Remaining Year Digits | Month | D o W | # | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Julian (r ÷ 7) |

Gregorian (r ÷ 4) | |||||||

| r5 19 | 16 20 r0 | 00 06 17 23 | 28 34 45 51 | 56 62 73 79 | 84 90 | Jan Oct | Sa | 0 |

| r4 18 | 15 19 r3 | 01 07 12 18 | 29 35 40 46 | 57 63 68 74 | 85 91 96 | May | Su | 1 |

| r3 17 | 02 13 19 24 | 30 41 47 52 | 58 69 75 80 | 86 97 | Feb Aug | M | 2 | |

| r2 16 | 18 22 r2 | 03 08 14 25 | 31 36 42 53 | 59 64 70 81 | 87 92 98 | Feb Mar Nov | Tu | 3 |

| r1 15 | 09 15 20 26 | 37 43 48 54 | 65 71 76 82 | 93 99 | Jun | W | 4 | |

| r0 14 | 17 21 r1 | 04 10 21 27 | 32 38 49 55 | 60 66 77 83 | 88 94 | Sep Dec | Th | 5 |

| r6 13 | 05 11 16 22 | 33 39 44 50 | 61 67 72 78 | 89 95 | Jan Apr Jul | F | 6 | |

Example: On what day does Feb 3, 4567 (Gregorian) fall?

1) The remainder of 45 / 4 is 1, so use the r1 entry: 5.

2) The remaining digits 67 give 6.

3) Feb (not Feb for leap years) gives 3.

4) Finally, add the day of the month: 3.

5) Adding 5 + 6 + 3 + 3 = 17. Dividing by 7 leaves a remainder of 3, so the day of the week is Tuesday.

Check the result

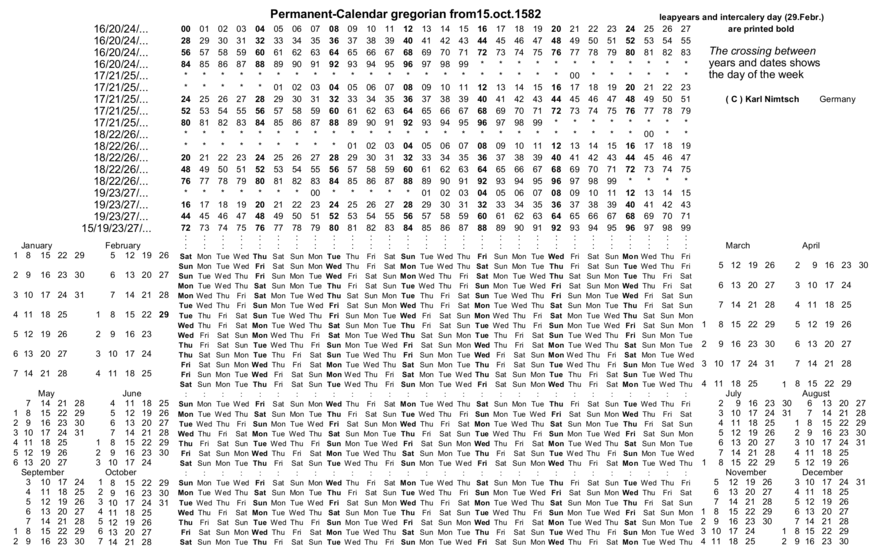

A result control is shown by the calendar period from 1582 October 15 possible, but only for Gregorian calendar dates.

See also

- Antikythera Mechanism

- Determination of the day of the week

- Doomsday rule

- Long Now Foundation

- Year 10,000 problem

References

- ↑ U.S. Patent 1,042,337, "Calendar (Fred P. Gorin)".

- ↑ U.S. Patent 248,872, "Calendar (Robert McCurdy)".

- ↑ "Aluminum Perpetual Calendar". 17 September 2011.

- ↑ Trude Ehlert, Rainer Leng, 'Frühe Koch- und Pulverrezepte aus der Nürnberger Handschrift GNM 3227a (um 1389)'; in: Medizin in Geschichte, Philologie und Ethnologie (2003), p. 291.

- ↑ "Mechanism Of Perpetual Calendar Watch". 17 September 2011.

- ↑ But see formula in preceding section, which is very easy to memorize.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Perpetual calendars. |

- New Perpetual Calendar for any year

- Perpetual Calendar in JavaScript

- Markl, Xavier (2016). "Monochrome-Watches A technical perspective calendar watches".

| Year starts | Common years | Leap years | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Jan | Count | Ratio | 31 Dec | DL | DD | Count | Ratio | 31 Dec | DL | DD | Count | Ratio | ||

| Sun | 58 | 14.50 % | Sun | A | Tue | 43 | 10.75 % | Mon | AG | Wed | 15 | 3.75 % | ||

| Sat | 56 | 14.00 % | Sat | B | Mon | 43 | 10.75 % | Sun | BA | Tue | 13 | 3.25 % | ||

| Fri | 58 | 14.50 % | Fri | C | Sun | 43 | 10.75 % | Sat | CB | Mon | 15 | 3.75 % | ||

| Thu | 57 | 14.25 % | Thu | D | Sat | 44 | 11.00 % | Fri | DC | Sun | 13 | 3.25 % | ||

| Wed | 57 | 14.25 % | Wed | E | Fri | 43 | 10.75 % | Thu | ED | Sat | 14 | 3.50 % | ||

| Tue | 58 | 14.50 % | Tue | F | Thu | 44 | 11.00 % | Wed | FE | Fri | 14 | 3.50 % | ||

| Mon | 56 | 14.00 % | Mon | G | Wed | 43 | 10.75 % | Tue | GF | Thu | 13 | 3.25 % | ||

| ∑ | 400 | 100.0 % | 303 | 75.75 % | 97 | 24.25 % | ||||||||

- ↑ Robert H. van Gent (2005). "Mathematics of the ISO calendar". Department of Mathematics at Utrecht University.