Ginseng

| Ginseng | |

|---|---|

| |

| Panax quinquefolius foliage and fruit | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Asterids |

| Order: | Apiales |

| Family: | Araliaceae |

| Subfamily: | Aralioideae |

| Tribe: | Aralieae |

| Genus: | Panax L. |

| Species | |

|

Subgenus Panax

Subgenus Trifolius | |

Ginseng (/ˈdʒɪnsɛŋ/[1]) is any one of the 11 species of slow-growing perennial plants with fleshy roots, belonging to the genus Panax of the family Araliaceae.

Ginseng is found in North America and in eastern Asia (mostly northeast China, Korea, Bhutan, eastern Siberia), typically in cooler climates. Panax vietnamensis, discovered in Vietnam, is the southernmost ginseng known. This article focuses on the species of the series Panax, which are the species claimed to be adaptogens, principally Panax ginseng and P. quinquefolius. Ginseng is characterized by the presence of ginsenosides and gintonin.

Siberian ginseng (Eleutherococcus senticosus) is in the same family, but not genus, as true ginseng. Like ginseng, it is considered to be an adaptogenic herb. The active compounds in Siberian ginseng are eleutherosides, not ginsenosides. Instead of a fleshy root, Siberian ginseng has a woody root.

Over centuries, ginseng has been considered in China as an important component of Chinese traditional medicine.[2]

Etymology

The English word ginseng derives from the Chinese term rénshēn (simplified: 人参; traditional: 人蔘, Mandarin pronunciation: [ɻə̌nʂə́n]). Rén means "Person" and shēn means "plant root"; this refers to the root's characteristic forked shape, which resembles the legs of a person.[3] The English pronunciation derives from a southern Chinese reading, similar to Cantonese yun sum (Jyutping: jan4sam1) and the Hokkien pronunciation "jîn-sim".

The botanical genus name Panax, meaning "all-healing" in Greek, shares the same origin as "panacea" and was applied to this genus because Linnaeus was aware of its wide use in Chinese medicine as a muscle relaxant.

Besides P. ginseng, many other plants are also known as or mistaken for the ginseng root. The most commonly known examples are xiyangshen, also known as American ginseng 西洋参 (P. quinquefolius), Japanese ginseng 東洋参 (P. japonicus), crown prince ginseng 太子參 (Pseudostellaria heterophylla), and Siberian ginseng 刺五加 (Eleutherococcus senticosus). Although all have the name "ginseng", each plant has distinctively different functions. However, true ginseng plants belong only to the Panax genus.[4]

History

Control over ginseng fields in China and Korea became an issue in the 16th century.[5] By the 1900s, due to the demand for ginseng having outstripped the available wild supply, Korea began the commercial cultivation of ginseng which continues to this day. In 2010, nearly all of the world's 80,000 tons of ginseng in international commerce was produced in four countries: China, South Korea, Canada,[6] and the United States.

Uses

Commercial ginseng is sold in over 35 countries with sales exceeded $2.1 billion, of which half came from South Korea in 2013.[7] China has historically been the largest consumer for ginseng.

The root is most often available in dried form, either whole or sliced. Ginseng leaf, although not as highly prized, is sometimes also used.

Ginseng may be found in small doses in energy drinks or herbal teas, such as ginseng coffee.[8]

Ginsenosides, unique chemical compounds of the Panax species, are being studied for their potential use in medicine.[9]

Folk medicine attributes various benefits to oral use of American ginseng and Asian ginseng (P. ginseng) roots, including roles as an aphrodisiac or stimulant treatment.[10][11][12]

Safety

Ginseng generally has a good safety profile and the incidence of adverse effects seems to be low.[13][14] Any adverse effects are usually mild and transient.[14]

Considerations

Ginseng is known to contain phytoestrogens.[15][16][17]

Side effects

Side effects can include nausea, diarrhea, headaches, nose bleeds,[18] high blood pressure, low blood pressure, and breast pains.[19]

Components of ginseng can elicit hypoglycemia in both normal and diabetic mice.[20]

Interactions

Ginseng has been shown to have adverse drug reactions with phenelzine and warfarin; it has been shown to decrease blood alcohol levels.[21] A potential interaction has also been reported with imatinib[22] resulting in hepatotoxicity, and with lamotrigine[23] causing DRESS syndrome.

Ginseng may also lead to induction of mania in depressed patients who mix it with antidepressants.[24]

Overdose

The common adaptogen ginsengs (P. ginseng and P. quinquefolia) are generally considered to be relatively safe even in large amounts. One of the most common and characteristic symptoms of acute overdose of Panax ginseng is bleeding. Symptoms of mild overdose may include dry mouth and lips, excitation, fidgeting, irritability, tremor, palpitations, blurred vision, headache, insomnia, increased body temperature, increased blood pressure, edema, decreased appetite, dizziness, itching, eczema, early morning diarrhea, bleeding, and fatigue.[4]

Symptoms of gross overdose with Panax ginseng may include nausea, vomiting, irritability, restlessness, urinary and bowel incontinence, fever, increased blood pressure, increased respiration, decreased sensitivity and reaction to light, decreased heart rate, cyanotic (blue) facial complexion, red facial complexion, seizures, convulsions, and delirium.[4]

Patients experiencing any of the above symptoms are advised to discontinue the herbs and seek any necessary symptomatic treatment, as well as medical advice in severe cases.[4]

Classification

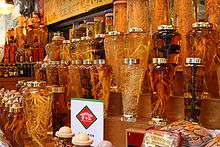

Asian ginseng (root)

Panax ginseng is available commercially as fresh, red, and white ginsengs; wild ginseng is used where available.

Red ginseng

Red ginseng (traditional Chinese: 紅蔘; simplified Chinese: 红参; pinyin: hóng shēn; Hangul: 홍삼; Hanja: 紅蔘; RR: hong-sam), P. ginseng, has been peeled, heated through steaming at standard boiling temperatures of 100 °C (212 °F), and then dried or sun-dried. It is frequently marinated in an herbal brew which results in the root becoming extremely brittle.

Fresh ginseng

Fresh ginseng is the raw product. Its use is limited by availability.

White ginseng

White ginseng, native to America, is fresh ginseng which has been dried without being heated. It is peeled and dried to reduce the water content to 12% or less. White ginseng air-dried in the sun may contain less of the therapeutic constituents. It is thought by some that enzymes contained in the root break down these constituents in the process of drying. Drying in the sun bleaches the root to a yellowish-white color.

Wild ginseng

Wild ginseng grows naturally and is harvested from wherever it is found. It is relatively rare, and even increasingly endangered, due in large part to high demand for the product in recent years, which has led to the wild plants being sought out and harvested faster than new ones can grow (it requires years for a root to reach maturity). Wild ginseng can be either Asian or American, and can be processed to be red ginseng.

Woods-grown American ginseng programs in Vermont, Maine, Tennessee, Virginia, North Carolina, Colorado, West Virginia and Kentucky,[25][26] and United Plant Savers have been encouraging the planting of ginseng both to restore natural habitats and to remove pressure from any remaining wild ginseng, and they offer both advice and sources of rootlets. Woods-grown plants have a value comparable to wild-grown ginseng of similar age.

Partially germinated ginseng seeds harvested the previous Fall can be planted from early Spring until late Fall, and will sprout the following Spring. If planted in a wild setting and left to their own devices, they will develop into mature plants which cannot be distinguished from native wild plants. Both Asian and American partially germinated ginseng seeds can be bought from May through December on various eBay sales. Some seed sales come with planting and growing instructions.

P. quinquefolius American ginseng (root)

Originally, American ginseng was imported into China via subtropical Guangzhou, the seaport next to Hong Kong, so Chinese doctors believed American ginseng must be good for yang, because it came from a hot area. They did not know, however, that American ginseng can only grow in temperate regions. Nonetheless, the root is legitimately classified as more yin because it generates fluids.[2]

Most North American ginseng is produced in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and British Columbia and the American state of Wisconsin.[27] P. quinquefolius is now also grown in northern China.

The aromatic root resembles a small parsnip that forks as it matures. The plant grows 6″ to 18″ tall, usually bearing three leaves, each with three to five leaflets two to five inches long.

Other plants sometimes called ginseng

Several other plants are sometimes referred to as ginsengs, but they are either from a different family or genus.

- Angelica sinensis (female ginseng, dong quai)

- Codonopsis pilosula (poor man's ginseng)

- Eleutherococcus senticosus (Siberian ginseng)

- Gynostemma pentaphyllum (southern ginseng, jiaogulan)

- Lepidium meyenii (Peruvian ginseng, maca)

- Oplopanax horridus (Alaskan ginseng)

- Panax notoginseng (known as san qi, tian qi or tien chi; ingredient in yunnan bai yao)

- Pfaffia paniculata (Brazilian ginseng, suma)

- Pseudostellaria heterophylla (prince ginseng)

- Schisandra chinensis (five-flavoured berry)

- Withania somnifera (Indian ginseng, ashwagandha)

See also

- Codonopsis pilosula "poor man's ginseng"

- Food therapy

- Herbalism

- List of herbs with known adverse effects

- Salvia miltiorrhiza

- Gintonin

References

- ↑ "ginseng". Cambridge Dictionaries Online. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- 1 2 Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, Third Edition by Dan Bensky, Steven Clavey, Erich Stonger, and Andrew Gamble 2004

- ↑ Oxford Dictionaries Online, s.v. "ginseng".

- 1 2 3 4 Chinese Medical Herbology and Pharmacology, by John K. Chen, Tina T. Chen

- ↑ Kim, Seonmin (2007). "Ginseng and Border Trespassing Between Qing China and Choson Korea". Late Imperial China. 28 (1): 33–61. doi:10.1353/late.2007.0009.

- ↑ Evans, Brian L. (1985). "Ginseng: Root of Chinese-Canadian Relations". Canadian Historical Review. 66 (1): 1–26. doi:10.3138/chr-066-01-01.

- ↑ Baeg, In-Ho; So, Seung-Ho (2013). "The world ginseng market and the ginseng". Journal of Ginseng Research. 37 (1): 1–7. doi:10.5142/jgr.2013.37.1. PMC 3659626

. PMID 23717152.

. PMID 23717152. - ↑ Clauson KA, Shields KM, McQueen CE, Persad N (2008). "Safety issues associated with commercially available energy drinks". J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 48 (3): e55–63; quiz e64–7. doi:10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07055. PMID 18595815.

- ↑ Qi LW, Wang CZ, Yuan CS (June 2011). "Ginsenosides from American ginseng: chemical and pharmacological diversity". Phytochemistry. 72 (8): 689–99. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.02.012. PMC 3103855

. PMID 21396670.

. PMID 21396670. - ↑ Kim, Sina; Shin, Byung-Cheul; Lee, Myeong Soo; Lee, Hyangsook; Ernst, Edzard (3 December 2011). "Red ginseng for type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 17 (12): 937–944. doi:10.1007/s11655-011-0937-2. PMID 22139546.

- ↑ Yeh, GY; Eisenberg, DM; Kaptchuk, TJ; Phillips, RS (April 2003). "Systematic review of herbs and dietary supplements for glycemic control in diabetes.". Diabetes Care. 26 (4): 1277–94. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.4.1277. PMID 12663610.

- ↑ Shishtar, E; Sievenpiper, JL; Djedovic, V; Cozma, AI; Ha, V; Jayalath, VH; Jenkins, DJ; Meija, SB; de Souza, RJ; Jovanovski, E; Vuksan, V (2014). "The effect of ginseng (the genus panax) on glycemic control: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials.". PLOS ONE. 9 (9): e107391. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0107391. PMC 4180277

. PMID 25265315.

. PMID 25265315. - ↑ Lee NH, Son CG (2011). "Systematic review of randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of ginseng". Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies. 4 (2): 85–97. doi:10.1016/S2005-2901(11)60013-7. PMID 21704950. Retrieved 2016-03-12.

ginseng generally has a good safety profile and the incidence of adverse effects seems to be low.

- 1 2 Coon JT, Ernst E (2002). "Panax ginseng: a systematic review of adverse effects and drug interactions". Drug Safety. 25 (5): 323–44. doi:10.2165/00002018-200225050-00003. PMID 12020172.

Collectively, these data suggest that P. ginseng monopreparations are rarely associated with adverse events or drug interactions. The ones that are documented are usually mild and transient.

- ↑ Lee YJ, Jin YR, Lim WC, et al. (January 2003). "Ginsenoside-Rb1 acts as a weak phytoestrogen in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells". Arch. Pharm. Res. 26 (1): 58–63. doi:10.1007/BF03179933. PMID 12568360.

- ↑ Chan RY, Chen WF, Dong A, Guo D, Wong MS (August 2002). "Estrogen-like activity of ginsenoside Rg1 derived from Panax notoginseng". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87 (8): 3691–5. doi:10.1210/jc.87.8.3691. PMID 12161497.

- ↑ Lee Y, Jin Y, Lim W, et al. (March 2003). "A ginsenoside-Rh1, a component of ginseng saponin, activates estrogen receptor in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 84 (4): 463–8. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(03)00067-0. PMID 12732291.

- ↑ "Ginseng definition - Medical Dictionary definitions of some medical terms defined on MedTerms". Medterms.com. 2012-09-20. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ Kiefer D, Pantuso T (October 2003). "Panax ginseng". Am Fam Physician. 68 (8): 1539–42. PMID 14596440.

- ↑ Hui H, Tang G, Go VL (2009). "Hypoglycemic herbs and their action mechanisms". Chinese Medicine. 4: 11. doi:10.1186/1749-8546-4-11. PMC 2704217

. PMID 19523223. Retrieved 2016-07-09.

. PMID 19523223. Retrieved 2016-07-09. Ginseng's clinical efficacy is thought to be medicated by multiple factors [27,28]: the component panaxans (panaxans A to E) elicits hypoglycemia in both normal and diabetic mice; the component adenosine inhibits catecholamine-induced lipolysis; both components of carboxylic acid and peptide 1400 inhibit catecholamine-induced lipolysis in rat epididymal fat pads; and the component DPG-3-2 provokes insulin secretion in diabetic and glucose-loaded normal mice [29].

- ↑ Izzo AA, Ernst E (2001). "Interactions between herbal medicines and prescribed drugs: a systematic review". Drugs. 61 (15): 2163–75. doi:10.2165/00003495-200161150-00002. PMID 11772128.

- ↑ Bilgi N, Bell K, Ananthakrishnan AN, Atallah E (2010). "Imatinib and Panax ginseng: a potential interaction resulting in liver toxicity". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 44 (5): 926–8. doi:10.1345/aph.1M715. PMID 20332334.

- ↑ Myers AP, Watson TA, Strock SB (2015). "Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms Syndrome Probably Induced by a Lamotrigine-Ginseng Drug Interaction". Pharmacotherapy. 35: e9–e12. doi:10.1002/phar.1550. PMID 25756365. Retrieved 2015-03-16.

- ↑ Fugh-Berman A (January 2000). "Herb-drug interactions". Lancet. 355 (9198): 134–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06457-0. PMID 10675182.

- ↑ state.tn.us TDEC: DNH: Ginseng Program

- ↑ "Care and Planting of Ginseng Seed and Roots". Ces.ncsu.edu. 1914-06-30. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ Agri-food Canada

Further reading

- Baeg, In-Ho; So, Seung-Ho (2013). "The world ginseng market and the ginseng". Journal of ginseng research. 37 (1): 1–7. doi:10.5142/jgr.2013.37.1. PMC 3659626

. PMID 23717152.

. PMID 23717152. - Evans, Brian L (1985). "Ginseng: Root of Chinese-Canadian Relations". Canadian Historical Review. 66 (1): 1–26. doi:10.3138/chr-066-01-01.

- Johannsen, Kristin (2006). Ginseng Dreams: The Secret World of America's Most Valuable Plant. University Press of Kentucky.

- Kim, Seonmin (2007). "Ginseng and Border Trespassing Between Qing China and Choson Korea". Late Imperial China. 28 (1): 33–61. doi:10.1353/late.2007.0009.

- Pritts, K.D. (2010). Ginseng: How to Find, Grow, and Use America´s Forest Gold. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3634-3

- Taylor, D.A. (2006). Ginseng, the Divine Root: The Curious History of the Plant That Captivated the World. Algonquin Books. ISBN 978-1-56512-401-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ginseng. |

- MedlinePlus-Ginseng - National Institutes of Health

- Asian Ginseng - NCCIH - National Institutes of Health