Ottoman Greeks

Ottoman Greeks (Greek: Οθωμανοί Έλληνες, Turkish: Osmanlı Rumları) were ethnic Greeks who lived in the Ottoman Empire (1453–1921), the Republic of Turkey's predecessor. Ottoman Greeks, who were Greek Orthodox Christians, belonged to the Rum Millet (Millet-i Rum). They were concentrated in what is today modern Greece, western Asia Minor (especially in and around Smyrni), central Anatolia (especially Cappadocia), northeastern Anatolia (especially in Erzurum vilayet, in and around Trebizond and in the Pontic Mountains (roughly corresponding to the medieval Greek kingdom of Pontus, which was situated along the southeastern shores of the Black Sea and the highlands of the interior). There were also sizeable Greek communities elsewhere in the Ottoman Balkans, Ottoman Armenia, and the Ottoman Caucasus, including in what, between 1878 and 1917, made up the Russian Caucasus province of Kars Oblast, in which Pontic Greeks, northeastern Anatolian Greeks, and Caucasus Greeks who had collaborated with the Russian Imperial Army in the Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829 were settled in over 70 villages, as part of official Russian policy to re-populate with Orthodox Christians an area that was traditionally made up of Ottoman Muslims and Armenians.

History

Introduction

In the Ottoman Empire, in accordance with the Muslim dhimmi system, Greeks, as Christians, were guaranteed limited freedoms (such as the right to worship), but were treated as second-class citizens. Christians and Jews were not considered equals to Muslims: testimony against Muslims by Christians and Jews was inadmissible in courts of law. They were forbidden to carry weapons or ride atop horses, their houses could not overlook those of Muslims, and their religious practices would have to defer to those of Muslims, in addition to various other legal limitations.[2] Violation of these statutes could result in punishments ranging from the levying of fines to execution.

The Ecumenical Patriarch was recognized as the highest religious and political leader (millet-bashi, or ethnarch) of all Orthodox Christian subjects of the Sultan, though in certain periods some major powers, such as Russia (under the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca of 1774), or Great Britain claimed the rights of protection over the Ottoman Empire's Orthodox subjects.

19th century

The three major European powers, Great Britain, France and Russia (known as the Great Powers), took issue with the Ottoman Empire's treatment of its Christian minorities and increasingly pressured the Ottoman government (also known as the Sublime Porte) to extend equal rights to all its citizens. Beginning in 1839, the Ottoman government implemented the Tanzimat reforms to improve the situation of minorities, although these would prove largely ineffective. In 1856, the Hatt-ı Hümayun promised equality for all Ottoman citizens irrespective of their ethnicity and confession, widening the scope of the 1839 Hatt-ı Şerif of Gülhane. The reformist period peaked with the Constitution, (or Kanûn-ı Esâsî in Ottoman Turkish), which was promulgated on November 23, 1876. It established freedom of belief and equality of all citizens before the law.

20th century

On July 24, 1908, Greeks' hopes for equality in the Ottoman Empire brightened with the removal of Sultan Abd-ul-Hamid II (r. 1876–1909) from power and restored the country back to a constitutional monarchy. The Committee of Union and Progress (more commonly called the Young Turks), a political party opposed to the absolute rule of Sultan Abd-ul-Hamid II, had led a rebellion against their ruler. The pro-reform Young Turks deposed the Sultan and replaced him with the ineffective Sultan Mehmed V (r. 1908–1918).

Before World War I, there were an estimated 1.8 million Greeks living in the Ottoman Empire.[3] Some prominent Ottoman Greeks served as Ottoman Parliamentary Deputies. In the 1908 Parliament, there were twenty-six (26) Ottoman Greek deputies but their number dropped to eighteen (18) by 1914.[4] It is estimated that the Greek population of the Ottoman Empire in Asia Minor had 2,300 community schools, 200,000 students, 5,000 teachers, 2,000 Greek Orthodox churches, and 3,000 Greek Orthodox priests.[5]

From 1914 until 1923, Greeks in Thrace and Asia Minor were subject to a campaign including massacres and internal deportations involving death marches. The International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) recognizes it as genocide and refers to the campaign as the Greek Genocide.[6]

Patriarchate of Constantinople

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, when the Sultan virtually replaced the Byzantine emperor among subjugated Christians, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople was recognized by the Sultan as the religious and national leader (ethnarch) of Greeks and the other ethnicities that were included in the Greek Orthodox Millet. The Patriarchate earned a primary importance and occupied this key role among the Christians of the Ottoman Empire because the Ottomans did not legally distinguish between nationality and religion, and thus regarded all the Orthodox Christians of the Empire as a single entity.

The position of the Patriarchate in the Ottoman state encouraged projects of Greek renaissance, centered on the resurrection and revitalization of the Byzantine Empire. The Patriarch and those church dignitaries around him constituted the first centre of power for the Greeks inside the Ottoman state, one which succeeded in infiltrating the structures of the Ottoman Empire, while attracting the former Byzantine nobility.

Identity

The Greeks were a self-conscious group within the larger Christian Orthodox religious community established by the Ottoman Empire.[7] They distinguished themselves from their Orthodox co-religionists by retaining their Greek culture, customs, language, and tradition of education.[7][8] Throughout the post-Byzantine and Ottoman periods, Greeks, as members of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, declared themselves as Graikoi (Greek: Γραικοί, "Greeks") and Romaioi or Romioi (Greek: Ρωμαίοι/Ρωμηιοί, "Romans").[9][10][11]

Notable Ottoman Greeks

- Aleksandro Karatodori (1833–1906).

- Basil Zaharoff (1850–1936), arms dealer and financier.

- Christakis Zografos (1820–1896), banker and benefactor.

- Elia Kazan (1909–2003), director, producer, writer and actor.

- Elias Venezis (1904–1973), writer from Ayvalık.

- Emanuel Emanuelides, Ottoman Parliamentary Deputy.

- Evangelinos Misailides (1820–1890).

- Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha (1855–1922), Grand Vizier.

- Pargali Ibrahim Pasha (1494–1536), Grand Vizier to Suleyman the Magnificent.

- Kösem Sultan (1589–1651), wife of Ottoman sultan Ahmed I.

- Marko Apostolides.

- Michael Vasileiou, 19th century merchant and benefactor.

- Nikolas Mavrokordatos (1670–1730).

- Prince Alexander Mavrocordatos (1791–1865), Greek statesman.

- Yorgo Zarifi (1810–1884), banker and financier.

- Aristotle Onassis (1906–1975), shipping magnate.

- Roza Eskenazi (1890–1980), famous singer.

- Rita Abatzi (1914–1969), famous singer.

- Marika Ninou (1918–1957), famous singer.

- Giannis Papaioannou (1913–1972), famous singer.

- Kostas Skarvelis (1880–1942), famous singer.

- Matthaios Kofidis (1855-1921), businessman and politician.

Gallery

-

Ethnological map depicting the Ottoman Greeks (blue) in 1910.

-

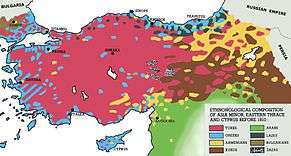

Map depicting the ethnic composition of Ottoman territories in 1911.

-

Declaration of the Constitution; Muslim, Greek and Armenian leaders together.

See also

- Asia Minor

- Greeks in Turkey

- Greek genocide

- Greek Orthodox Church

- Greek Muslims

- Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople

- Millet (Ottoman Empire)

- Ottoman Empire

- Ottoman Armenians

- Phanar Greek Orthodox College

- Timeline of Orthodoxy in Greece (1453–1821)

- Pontic Greeks

- Greek Byzantine Catholic Church

References

Citations

- ↑ Dawkins & Halliday 1916.

- ↑ Akçam 2006, p. 24.

- ↑ Alaux & Puaux 1916.

- ↑ Roudometof & Robertson 2001, p. 91.

- ↑ Lekka 2007, p. 136: "At the start of the war, the Greeks were a thriving community in Asia Minor, a land they had inhabited since the time of Homer. But things deteriorated quickly. Before the Turkish implementation of a nationalist policy, the Greek population was estimated at around 2.5 million, with 2,300 community schools, 200,000 pupils, 5,000 teachers, 2,000 Greek Orthodox churches, and 3,000 Greek Orthodox priests."

- ↑ International Association of Genocide Scholars (December 16, 2007). "Genocide Scholars Association Officially Recognizes Assyrian, Greek Genocides" (PDF). Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- 1 2 Harrison 2002, pp. 276–277: "The Greeks belonged to the community of the Orthodox subjects of the Sultan. But within that larger unity they formed a self-conscious group marked off from their fellow Orthodox by language and culture and by a tradition of education never entirely interrupted, which maintained their Greek identity."

- ↑ Volkan & Itzkowitz 1994, p. 85: "While living as a millet under the Ottoman Empire they retained their own religion, customs, and language, and the 'Greeks became the most important non-Turkish element in the Ottoman Empire'."

- ↑ Kakavas 2002, p. 29: "All the peoples belonging to the flock of the Ecumenical Patriarchate declared themselves Graikoi (Greeks) or Romaioi (Romans - Rums)."

- ↑ Institute for Neohellenic Research 2005, p. 8: "The people we have named as Greeks (Hellenes in the Greek language) would not describe themselves as such – they are generally known as Romioi and Graikoi – but according to their context the meaning of these words broadens to include or exclude population groups of another language and, at the same time, ethnicity."

- ↑ Hopf 1873, "Epistola Theodori Zygomalae", p. 236: "...ησάν ποτε κύριοι Αθηνών, και ενωτίζοντο, ότι η νέων Ρωμαίων είτε Γραικών βασιλεία ασθενείν άρχεται..."

Sources

- Akçam, Taner (2006). A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility. New York, New York: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 0-8050-7932-7.

- Alaux, Louis-Paul; Puaux, René (1916). Le Déclin de l’Hellénisme. Paris, France: Librairie Payot & Cie.

- Bator, Robert; Rothero, Chris (2000). Daily Life in Ancient and Modern Istanbul. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Runestone Press. ISBN 0-8225-3217-4.

- Dawkins, Richard McGillivray; Halliday, William Reginald (1916). Modern Greek in Asia Minor: A Study of Dialect of Silly, Cappadocia and Pharasa with Grammar, Texts, Translations and Glossary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harrison, Thomas (2002). Greeks and Barbarians. New York, New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-93958-5.

- Hopf, Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann (1873). Chroniques Gréco-Romanes Inédites ou peu Connues. Berlin, Germany: Librairie de Weidmann.

- Institute for Neohellenic Research (2005). The Historical Review. II. Athens, Greece: Institute for Neohellenic Research.

- Kakavas, George (2002). Post-Byzantium: The Greek Renaissance 15th-18th Century Treasures from the Byzantine & Christian Museum, Athens. Athens, Greece: Hellenic Ministry of Culture. ISBN 960-214-053-4.

- Lekka, Anastasia (2007). "Legislative Provisions of the Ottoman/Turkish Governments Regarding Minorities and Their Properties". Mediterranean Quarterly. 18 (1): 135–154. doi:10.1215/10474552-2006-038.

- Roudometof, Victor; Robertson, Roland (2001). Nationalism, Globalization, and Orthodoxy: The Social Origins of Ethnic Conflict in the Balkans. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Volkan, Vamik D.; Itzkowitz, Norman (1994). Turks and Greeks: Neighbours in Conflict. Huntingdon, United Kingdom: The Eothen Press. ISBN 0-906719-25-9.

Further reading

- Gondicas, Dimitri; Issawi, Charles Philip, eds. (1999). Ottoman Greeks in the Age of Nationalism: Politics, Economy, and Society in the Nineteenth Century. Princeton, New Jersey: Darwin Press. ISBN 0-87850-096-0.

- Clogg, Richard (2004). I Kath’imas Anatoli: Studies in Ottoman Greek History. Istanbul, Turkey: The Isis Press.