Kimberley, Northern Cape

| Kimberley | |

|---|---|

|

City centre seen over the Big Hole | |

Kimberley  Kimberley  Kimberley

| |

| Coordinates: 28°44′31″S 24°46′19″E / 28.74194°S 24.77194°ECoordinates: 28°44′31″S 24°46′19″E / 28.74194°S 24.77194°E | |

| Country | South Africa |

| Province | Northern Cape |

| District | Frances Baard |

| Municipality | Sol Plaatje |

| Established | 1873-07-05 |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 164.3 km2 (63.4 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,184 m (3,885 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 225,160 |

| • Density | 1,400/km2 (3,500/sq mi) |

| Racial makeup (2011)[1] | |

| • Black African | 63.1% |

| • Coloured | 26.8% |

| • Indian/Asian | 1.2% |

| • White | 8.0% |

| • Other | 0.9% |

| First languages (2011)[1] | |

| • Afrikaans | 43.2% |

| • Tswana | 35.8% |

| • English | 8.7% |

| • Xhosa | 6.0% |

| • Other | 6.3% |

| Postal code (street) | 8301 |

| PO box | 8300 |

| Area code | 053 |

Kimberley is the capital of the Northern Cape Province of South Africa. It is located approximately 110 km east of the confluence of the Vaal and Orange Rivers. The city has considerable historical significance due to its diamond mining past and the siege during the Second Boer War. Notable personalities such as Cecil Rhodes and Barney Barnato made their fortunes here, and the roots of the De Beers company can also be traced to the early days of the mining town.

Kimberley was the first city in the Southern Hemisphere and the second in the world after Philadelphia to integrate electric street lights into its infrastructure on Sept. 2, 1882. The first Stock Exchange in Africa was also built in Kimberley, as early as 1881.[2]

History

Discovery of diamonds

In 1866, Erasmus Jacobs found a small brilliant pebble on the banks of the Orange River, on the farm De Kalk leased from local Griquas, near Hopetown, which was his father's farm. He showed the pebble to his father who sold it.[3] The pebble was purchased from Jacobs by Schalk van Niekerk, who later sold it. It proved to be a 21.25-carat (4.3 g) diamond, and became known as the Eureka. Three years later, in 1869, an 83.5-carat (16.7 g) diamond, which became known as the Star of South Africa, was found nearby (29°3′S 23°58′E / 29.050°S 23.967°E).[4][5] This diamond was sold by van Niekerk for £11,200 and later resold in the London market for £25,000.[3]

Henry Richard Giddy recounted how Esau Damoense (or Damon), the cook for prospector Fleetwood Rawstone's "Red Cap Party", found diamonds in 1871 on Colesberg Kopje after he was sent there to dig as punishment.[6] Rawstorne took the news to the nearby diggings of the De Beer brothers — his arrival there sparking off the famous "New Rush" which, as historian Brian Roberts puts it, was practically a stampede. Within a month 800 claims were cut into the hillock which were worked frenetically by two to three thousand men. As the land was lowered so the hillock became a mine – in time, the world-renowned Kimberley Mine.[7]

The Cape Colony, Transvaal, Orange Free State and the Griqua leader Nikolaas Waterboer all laid claim to the diamond fields. The Free State Boers in particular wanted the area as it lay inside the natural borders created by Orange and Vaal Rivers. Following the mediation that was overseen by the governor of Natal, the Keate Award went in favour of Waterboer, who placed himself under British protection.[8] Consequently, the territory known as Griqualand West was proclaimed on 27 October 1871.

Naming the place: from Vooruitzigt to New Rush to Kimberley

Colonial Commissioners arrived in New Rush on 17 November 1871 to exercise authority over the territory on behalf of the Cape Governor. Digger objections and minor riots led to Governor Barkly's visit to New Rush in September the following year, when he revealed a plan instead to have Griqualand West proclaimed a Crown Colony. Richard Southey would arrive as Lieutenant-Governor of the intended Crown Colony in January 1873. Months passed however without any sign of the proclamation or of the promised new constitution and provision for representative government. The delay was in London where Secretary of State for the Colonies, Lord Kimberley, insisted that before electoral divisions could be defined, the places had to receive "decent and intelligible names. His Lordship declined to be in any way connected with such a vulgarism as New Rush and as for the Dutch name, Vooruitzigt … he could neither spell nor pronounce it."[9] The matter was passed to Southey who gave it to his Colonial Secretary J.B. Currey. Roberts writes that "when it came to renaming New Rush, [Currey] proved himself a worthy diplomat. He made quite sure that Lord Kimberley would be able both to spell and pronounce the name of the main electoral division by, as he says, calling it 'after His Lordship'." New Rush became Kimberley, by Proclamation dated 5 July 1873.[9] Digger sentiment was expressed in an editorial in the Diamond Field newspaper when it stated "we went to sleep in New Rush and waked up in Kimberley, and so our dream was gone."[10]

Following agreement by the British government on compensation to the Orange Free State for its competing land claims, Griqualand West was annexed to the Cape Colony in 1877.[11] The Cape Prime Minister John Molteno initially had serious doubts about annexing the heavily indebted region, but, after striking a deal with the Home Government and receiving assurances that the local population would be consulted in the process, he passed the Griqualand West Annexation Act on 27 July 1877.[12]

The Big Hole and other mines

As miners arrived in their thousands the hill disappeared and subsequently became known as the Big Hole (or Kimberley se Gat in Afrikaans) or, more formally, Kimberley Mine. From mid-July 1871 to 1914, 50,000 miners dug the hole with picks and shovels, yielding 2,722 kg of diamonds. The Big Hole has a surface of 17 hectares (42 acres) and is 463 metres wide. It was excavated to a depth of 240 m, but then partially infilled with debris reducing its depth to about 215 m; since then it has accumulated water to a depth of 40 m leaving 175 m visible. Beneath the surface, the Kimberley Mine underneath the Big Hole was mined to a depth of 1097 metres. A popular local myth claims that it is the largest hand-dug hole on the world, however Jagersfontein Mine appears to hold that record.[13] The Big Hole is the principal feature of a May 2004 submission which placed "Kimberley Mines and associated early industries" on UNESCO's World Heritage Tentative Lists.[14][15]

By 1873 Kimberley was the second largest town in South Africa, having an approximate population of 40,000.[16]

Role and influence of De Beers

The various smaller mining companies were amalgamated by Cecil Rhodes and Charles Rudd into De Beers, and The Kimberley under Barney Barnato. In 1888, the two companies merged to form De Beers Consolidated Mines, which once had a monopoly over the world's diamond market.[17][18]

Very quickly, Kimberley became the largest city in the area, partly due to a massive African migration to the area from all over the continent. The immigrants were accepted with open arms, because the De Beers company was in search of cheap labour to help run the mines. Another group drawn to the city for money was prostitutes, from a wide variety of ethnicities who could be found in bars and saloons. It was praised as a city of limitless opportunity.[19]

Five big holes were dug into the earth following the kimberlite pipes, which are named after the town. Kimberlite is a diamond-bearing blue ground that sits below a yellow colored soil.[20] The largest, The Kimberley mine or "Big Hole" covering 170,000 square metres (42 acres), reached a depth of 240 metres (790 ft) and yielded three tons of diamonds. The mine was closed in 1914, while three of the holes – Dutoitspan, Wesselton and Bultfontein – closed down in 2005.

Second Boer War

On 14 October 1899, Kimberley was besieged at the beginning of the Second Boer War. The British forces trying to relieve the siege suffered heavy losses. The siege was only lifted on 15 February 1900, but the war continued until May 1902. By that time, the British had built a concentration camp at Kimberley to house Boer women and children.[21]

City of Kimberley

The hitherto separately administered Boroughs of Kimberley and Beaconsfield amalgamated as the City of Kimberley in 1912.[22]

Kimberley under Apartheid

Although a considerable degree of urban segregation already existed, one of the most significant impacts of Apartheid on the city of Kimberley was the implementation of the Group Areas Act. Communities were divided according to legislated racial categories, namely European (White), Native (Black), Coloured and Indian – now legally separated by the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act. Individual families could be split up to three ways (based on such notorious measures as the 'pencil test') and mixed communities were either completely relocated (as in Malay Camp – although those clearances began before Apartheid as such) or were selectively cleared (as in Greenpoint which became a ‘Coloured’ Group Area, its erstwhile African and other residents being removed to other parts of town). Residential segregation was thus enforced in a process which saw the creation of new townships at the northern and north-eastern edges of the expanding city. Institutions that were hard hit by the Group Areas Act, Bantu Education and other Acts included churches (such as the Bean Street Methodist Church) and schools (some, such as William Pescod and Perseverance School, moved while the Gore Browne (Native) Training School was closed down). Other legislation restricted the movement of Africans and some public places became ‘Europeans Only’ preserves in terms of the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act. The Native Laws Amendment Act sought to cleave church communities along racial lines – a law rejected on behalf of all Anglicans in South Africa by Archbishop Clayton in 1957 (in terms of which this aspect of apartheid was never completely implemented in churches such as Kimberley’s St Cyprian’s Cathedral).[23][24]

Resistance to apartheid in Kimberley was mounted as early as mid-1952 as part of the Defiance Campaign. Dr Arthur Letele put together a group of volunteers to defy the segregation laws by occupying 'Europeans Only’ benches at Kimberley Railway Station – which led to arrest and imprisonment. Later in the year, the Mayibuye Uprising in Kimberley, on 8 November 1952, revolved around the poor quality of beer served in the beer hall. The fracas resulted in shootings and a subsequent mass funeral on 12 November 1952 at Kimberley’s West End Cemetery. Detained following the massacre were alleged ‘ring-leaders’ Dr Letele, Sam Phakedi, Pepys Madibane, Olehile Sehume, Alexander Nkoane, Daniel Chabalala and David Mpiwa.[25] Archdeacon Wade of St Matthew’s Church, as a witness at the subsequent inquiry, placed the blame squarely on the policy of apartheid – including poor housing, lighting and public transport, together with "unfulfilled promises" – which he said "brought about the conditions which led to the riots."[26]

A later generation of anti-apartheid activists based in Kimberley included Phakamile Mabija and two post-apartheid provincial premiers, Manne Dipico and Dipuo Peters.

Other prominent figures of the struggle against apartheid who had Kimberley connections include Robert Sobukwe, founder of the Pan Africanist Congress, who was banished (placed under house arrest) in Kimberley after his release from Robben Island in 1969. He died in the city in 1978.

Benny Alexander (1955–2010), who later changed his name to Khoisan X, and was General Secretary of the Pan Africanist Congress and of the Pan-Africanist Movement from 1989, was born and grew up in Kimberley. Another leading figure in Coloured politics in the apartheid era was Sonny Leon.

Post-Apartheid

The Northern Cape Province became a political fact in 1994, with Kimberley as its capital. Some quasi provincial infrastructure was in place from the 1940s, but in the post-1994 period Kimberley underwent considerable development as administrative departments were set up and housed for the governance of the new province. A Northern Cape Legislature was designed and situated to bridge the formerly divided city. The Kimberley City Council of the renamed Sol Plaatje Local Municipality (see below) was enlarged. A new Coat of Arms and Motto for the city were ushered in.

With the abolition of apartheid previously ‘whites only’ institutions such as schools became accessible to all, as did suburbs previously segregated by the Group Areas Act. In practice this process has been one of upward mobility by those who could afford the more costly options, while by far the majority of Black people remain in the townships where poverty levels are high.

Major township residential developments, with 'RDP housing', were implemented – not without criticism concerning quality. There has been an increase in Kimberley’s population, urbanization being spurred on in part by the abolition of the Influx Control Act.

Also added to the city is the settlement of Platfontein created when the !Xun and Khwe community formerly of Schmidtsdrift and originally from Angola/Namibia acquired the land in 1996. Most of the community had moved to the new township by the end of 2003.

In 1998 the Kimberley Comprehensive Urban Plan estimated that Kimberley had 210,800 people representing 46,207 households living in the city.

By 2008 estimates were in the region of 250,000 inhabitants.

Name changes

The shifts from frontier farm names to digger camp names to the established names of the towns of Kimberley and Beaconsfield – which duly amalgamated in 1912 – are outlined above. The only traces of any precolonial settlement within the city's boundaries are scatters of Stone Age artefacts and there is no record of what the place/s might have been called before the first nineteenth century frontier overlay of farm names. It lay beyond the areas occupied by Tswana people in the precolonial period.[27] Sites such as the nearby Wildebeest Kuil testify to a Khoe–San history dating up into the nineteenth century.

In the post-1994 era the Kimberley City Council was renamed the Sol Plaatje Local Municipality after the area it served was expanded to include surrounding towns and villages, most notably Ritchie. Sol Plaatje, the prominent writer and activist, lived for much of his life in Kimberley. Similarly the erstwhile Diamantveld District Council became the Frances Baard District Municipality, with reference to the trade unionist, Frances Baard, who was born in Greenpoint, Kimberley.

Coats of arms

Municipality — The Kimberley borough council assumed a coat of arms in 1878.[28][29] The arms were registered with the Cape Provincial Administration in December 1964[30] and at the Bureau of Heraldry in February 1968.[31]

The design was a combination of the Union Jack and the charges from the Cape Colony's coat of arms, with a lozenge to represent the diamond-mining industry : Azure, a cross and saltire superimposed Gules both fimbriated Argent, in chief three bezants Or, each charged with a fleur de lis Azure, and in base three annulets Or; on a lozenge Or, superimposed over the fess point, a lion rampant Gules. The motto was "Spero meliora".[32]

Divisional council — The Kimberley divisional council, which administered the rural areas outside the city, registered its own arms at the Bureau in August 1970.[31]

The arms were : Per saltire, in chief, barry wavy of six Argent and Azure; in base, Argent, a pale Sable charged with three fusils Argent; dexter, Gules, a shovel and pick in saltire, handles downward, Or; sinister, a staff of Aesculapius, Or. In layman's terms, the shield was divided in four by two diagonal lines, and depicted (1) six silver and blue stripes with wavy edges, (2) a crossed pick and shovel on a red background, (3) a golden staff of Aesculapius, and (4) three silver diamond-shaped fusils on a black vertical stripe on a silver background.

The crest was two crossed rifles in front of an upright sword; the supporters were two kudus; and the motto was "Nitanir semper ad optima".

Economy: Kimberley’s changing commercial fortunes

Kimberley was the initial hub of industrialisation in South Africa in the late nineteenth century, which transformed the country’s agrarian economy into one more dependent on its mineral wealth. A key feature of the new economic arrangement was migrant labour, with the demand for African labour in the mines of Kimberley (and later on the gold fields) drawing workers in growing numbers from throughout the subcontinent. The labour compound system developed in Kimberley from the 1880s was later replicated on the gold mines and elsewhere.[33]

The city housed South Africa's first stock exchange, the Kimberley Royal Stock Exchange, which opened on 2 February 1881.[33]

On 2 September 1882, Kimberley became the first town in the Southern Hemisphere to install electric street lighting.[34][35][36]

The rising importance of Kimberley led to one of the earliest South African and International Exhibitions to be staged in Kimberley in 1892. It was opened by Sir Henry Loch, the then Governor of the Cape of Good Hope on 8 September. It presented exhibits of art, an exhibition of paintings from the royal collection of Queen Victoria and mining machinery and implements amongst other items. The exhibition aroused considerable interest at international level, which resulted in a competition for display space.

South Africa's first school of mines was opened here in 1896 and later relocated to Johannesburg, becoming the core of the University of the Witwatersrand. A Pretoria campus later became the University of Pretoria. In fact the first two years were attended at colleges elsewhere, in Cape Town, Grahamstown or Stellenbosch, the third year in Kimberley and the fourth year in Johannesburg. Buildings were constructed against a total cost of 9,000 pounds with De Beers contributing on a pound for pound basis.

Transport

Aviation, Kimberley Airport and air transport

South Africa's first school of aviation, to train pilots for the proposed South African Aviation Corps (SAAC), was established in Kimberley in 1913.[37] Known as Paterson's Aviation Syndicate School of Flying, it is commemorated in the Pioneers of Aviation Museum (and replica of the first Compton Patterson Biplane preserved there), situated near to Kimberley airport. In the 1930s Kimberley boasted the best night-landing facilities on the continent of Africa. A major air rally was hosted there in 1934. In the war years Kimberley Airport was commandeered by the Union Defence Force and run by the 21 Flying School for the training of fighter pilots.[22]

Today Kimberley Airport (IATA: KIM, ICAO: FAKM) services the area, with regular scheduled flights from Cape Town and Johannesburg.

Railways

Work on connecting Kimberley by rail to the cities along the Cape Colony's coastline began in 1872, under the management of the Cape Government Railways.[38] The railway line from Cape Town to Kimberley was completed in 1885, accelerating the transport of both passengers and goods.[22] The railway connected Kimberley with cheaper sources of grain and other products, as well as supplies of coal, so that one of its local impacts was to undercut (mainly African) trade in fresh produce and firewood in Kimberley’s hinterland.[39] Another footnote to railway history is its role in the initial rapid spread of the Spanish Influenza epidemic in 1918.

The railway reticulation eventually would link Kimberley with Port Elizabeth, Johannesburg, Durban and Bloemfontein. The major junction at De Aar in the Karoo linked early twentieth century lines to Upington (later to Namibia) and to Calvinia. From the 1990s there was a decline in the use of the railways.

- Today passenger train services to and from Kimberley are provided by Spoornet's Shosholoza Meyl, with connections south to Cape Town and Port Elizabeth and north to Johannesburg. Luxury railway experiences are provided on the main north-south line by the Blue Train and Rovos Rail.

Roads

Wagon and coach routes were developed rapidly as the rush for the diamond fields gathered momentum. Two of the major routes were from the Cape and from Port Elizabeth, the nearest maritime port at the time. Contemporary accounts of the 1870s describe the appalling condition of some of the roads and decry the absence of bridges.[40] From the mid-1880s the route through Kimberley and Mafeking (now Mahikeng) became the main axis of British colonial penetration and it was from Kimberley, along that route, that the Pioneer Column for the settlement of Rhodesia set forth in 1890. Today, however, the central arterial route to the north, the N1 from the Cape to Johannesburg, goes via Bloemfontein, not Kimberley.

Kimberley today

Today, Kimberley is the seat of the Provincial Legislature for the Northern Cape and the Provincial Administration. It services the mining and agricultural sectors of the region.

Tourism

The city projects itself as a significant tourist destination, the ‘City that Sparkles’, boasting a diversity of museums and visitor attractions. It is also a gateway to other Northern Cape destinations including the Mokala National Park, nature reserves and numerous game farms or hunting lodges, as well as historic sites of the region.

Conference-hosting

Kimberley has hosted significant meetings and conferences, developing a major venue, the Mittah Seperepere Convention Centre, and other conference hosting facilities. Recent gatherings have included the founding meeting of the Kimberley Process (2000) and a follow-up meeting of this organisation in 2013, and the International Indigenous Peoples Summit on Sustainable Development (2002).

Climate and Geography

Climate

| Climate data for Kimberley (1961–1990, extremes 1877–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 43.3 (109.9) |

43.6 (110.5) |

38.2 (100.8) |

37.5 (99.5) |

31.1 (88) |

27.8 (82) |

27.2 (81) |

31.6 (88.9) |

36.6 (97.9) |

39.7 (103.5) |

39.2 (102.6) |

40.9 (105.6) |

43.6 (110.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32.8 (91) |

31.0 (87.8) |

28.8 (83.8) |

24.7 (76.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.5 (77.9) |

27.8 (82) |

30.2 (86.4) |

32.1 (89.8) |

26.1 (79) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 25.1 (77.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

17.3 (63.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.8 (55) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.7 (67.5) |

22.2 (72) |

24.2 (75.6) |

18.1 (64.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) |

17.3 (63.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

6.5 (43.7) |

3.2 (37.8) |

2.8 (37) |

4.9 (40.8) |

8.9 (48) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.6 (61.9) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.7 (42.3) |

5.6 (42.1) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−2.8 (27) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

2.2 (36) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−8.5 (16.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 57 (2.24) |

76 (2.99) |

65 (2.56) |

49 (1.93) |

16 (0.63) |

7 (0.28) |

7 (0.28) |

7 (0.28) |

12 (0.47) |

30 (1.18) |

42 (1.65) |

46 (1.81) |

414 (16.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 49 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 45 | 53 | 57 | 59 | 54 | 53 | 48 | 41 | 36 | 40 | 42 | 42 | 47 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 307.1 | 260.7 | 265.7 | 262.0 | 281.2 | 264.2 | 286.7 | 299.3 | 288.3 | 305.1 | 310.6 | 331.0 | 3,461.9 |

| Source #1: NOAA,[41] Deutscher Wetterdienst (June record high, November record low),[42] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[43] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: South African Weather Service[44] | |||||||||||||

| Kimberley | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Water

Kimberley’s water is pumped from the Vaal River at Riverton, some 15 km north of the city.

Districts/Suburbs/Townships

- Albertynshof

- Ashburnham

- Beaconsfield

- Belgravia

- Carters Glen

- Cassandra

- Colville

- De Beers

- Diamant Park

- Du Toit's Pan

- El Torro Park

- Ernestville

- Floors/Florianville

- Galeshewe incl "Old No 2"

- Gemdene

- Greenpoint

- Greenside

- Hadison Park

- Herlear

- Heuwelsig

- Hillcrest

- Homelite

- Homestead

- Homevale

- Kenilworth

- Kestellhof

- Kimberley North

- Kirstenhof

- Klisserville

- Labram

- Lindene

- Malay Camp

- Minerva Gardens

- Mint Village

- Moghul Park

- Monument Heights

- Newton

- New Park

- Platfontein

- Rhodesdene

- Riviera

- Roodepan/Pescodia

- Royldene

- Roylglen

- Southridge

- Squarehill Park

- Vergenoeg

- Verwoerd Park

- West End

Demography

According to the 2011 census, the population of Kimberley "proper" was 96,977,[45] while the townships Galeshewe and Roodepan had populations of 107,920[46] and 20,263[47] respectively. This gives the urban area a total population of 225,160. Of this population, 63.1% identified themselves as "Black African", 26.8% as "Coloured", 8.0% as "White" and 1.2% as "Indian or Asian". 43.2% of the population spoke Afrikaans as their first language, 35.8% spoke Setswana, 8.7% spoke English, 6.0% spoke isiXhosa and 2.7% spoke Sesotho.

Landscapes, urban and rural

Kimberley is set in a relatively flat landscape with no prominent topographic features within the urban limits. The only "hills" are debris dumps generated by more than a century of diamond mining. From the 1990s these were being recycled and poured back into De Beers Mine (by 2010 it was filled to within a few tens of metres of the surface). Certain of the mine dumps, in the vicinity of the Big Hole, have been proclaimed as heritage features and are to be preserved as part of the historic industrial landscape of Kimberley.

The surrounding rural landscape, not more than a few minutes’ drive from any part of the city, consists of relatively flat plains dotted with hills, mainly outcropping basement rock (andesite) to the north and north west, or Karoo age dolerite to the south and east. Shallow pans formed in the plains.

One of Kimberley’s famous features is Kamfers Dam, a large pan north of the city, which is an important wetland supporting a breeding colony of lesser flamingos. Conservation initiatives in the area aim to bring people from the city in touch with its wildlife. In 2012 rising water levels flooded the artificial island built to enhance flamingo breeding, while in December 2013 a local outbreak of avian botulism bacteria resulted in the deaths of hundreds of birds.[48] The island has since re-emerged.

Government, local and provincial

The administration of the Crown Colony of Griqualand West (from 1873) was conducted from Government Buildings in Kimberley up until the annexation of the Colony to the Cape in 1880. At the level of local government, separate Borough Councils operated in Kimberley and Beaconsfield up to the time of their amalgamation as the City of Kimberley in 1912. Thereafter a single City Council regulated the affairs of the city, while a Divisional Council administered the surrounding rural district. In the 1980s, in the last days of apartheid, a separate political entity referred to as Galeshewe (with Mankurwane) was brought into existence with its own council.

Post-1994 the Kimberley City Council became the Sol Plaatje Local Municipality while the successor to what had become the Diamandveld Regional Services Council was the Frances Baard District Municipality.

The idea of establishing the Northern Cape as a distinct geographic entity dates from the 1940s but it became a political and administrative fact only in 1994, with Kimberley formally becoming the new province’s legislative capital. The provincial legislature initially occupied the old Cape Provincial Administration building at the Civic Centre before moving into a purpose-built Legislature deliberately situated between one of the townships and erstwhile white suburbs. Kimberley is also the seat of the Northern Cape Division of the High Court of South Africa, which exercises jurisdiction over the province.

Education

Education is a major sector in Kimberley's social and economic life.

Primary education

- Beacon Primary School

- Diamantveld Laerskool

- Eureka Primary School

- Flamingo Primary School

- Floors North Primary School

- Herlear Primary School

- Isago Primary School

- Kim Kgolo Primary School

- Kimberley Junior School

- Letshego Primary School

- Masiza Primary School

- Molehabangwe Primary School

- Montshiwa Primary School

- Newton Primary School

- St Cyprian's Grammar School

- St Peters Primary School

- Staat President Swart Primary School (now known as Staats Primary School)

- West End Primary School

- Zingisa Primary School

- Vooruitsig Primary School

Secondary education

- Adamantia Hoërskool

- Diamantveld Hoërskool

- Dr E.P Lekhela High School

- Elizabeth Conradie School "Elcon" (primary and secondary) for children with physical disabilities.

- Emmang Mmogo Comprehensive School

- Floors High School

- Homevale High School

- Kimberley Boys' High School

- Kimberley Girls' High School

- Northern Cape High School

- St. Boniface High School, Galeshewe

- St Cyprian's Grammar School

- St Patrick's College, Kimberley, formerly CBC Kimberley

- Technical High School Kimberley (HTS Kimberley)

- Tetlanyo High School

- Thabane High School

- Tlhomelang High School

- William Pescod High School

Tertiary education

- Henrietta Stockdale Training College for nurses

- Kimberley Academy of Music aligned with NIHE

- National Institute of Higher Education, Kimberley, incorporating the former Phatsimang and Perseverance Colleges

- Northern Cape Urban FET College, incorporating the former Northern Cape, Moremogolo and RC Elliott Technical Colleges

- Qualitas Career Academy, (Nationally brand, private college). Offering full-time and part-time studies for students as well as corporate training and consulting services for businesses and government departments.

Sol Plaatje University

The Sol Plaatje University opened in Kimberley in 2014, accommodating a modest initial intake of 135 students. Announcing the name for the university, President Jacob Zuma mentioned the development of academic niche areas that did not exist elsewhere, or were under-represented, in South Africa. "Given the rich heritage of Kimberley and the Northern Cape in general," Zuma said, "it is envisaged that Sol Plaatje will specialise in heritage studies, including interconnected academic fields such as museum management, archaeology, indigenous languages, and restoration architecture."[49][50][51][52]

Defunct tertiary institutions

Tertiary education institutions no longer in existence (or absorbed into the above organisational configurations):

- Gore Browne Training Institute

- Moremogolo Technical College / Taemaneng Technical Centre

- Northern Cape Technical College

- Perseverance Teachers' Training College

- Phatsimang Teachers' Training College

- RC Elliott Technical College

Society and culture

Religion

Kimberley, from its earliest days, attracted people of diverse faiths which are still reflected by practising faith communities in the city. Pre-eminently these are various denominations of Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Hinduism, as well as other faiths. Traditional African beliefs continue as an element in the Zionist Christian Church (ZCC). Kimberley is the seat of the Anglican Diocese of Kimberley and Kuruman and also of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Kimberley – previously the Apostolic Vicariate of Kimberley in Orange. Other denominations having churches in the city are the Methodist Church, the Presbyterian Church, the Congregational Church, the Dutch Reformed Church (Afrikaans: Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk), the Baptist Church, the Afrikaans Baptist Church (Afrikaans: Afrikaanse Baptiste Kerk), the Apostolics, Pentecostalists. The Seventh-day Adventist Church in South Africa was first established in Kimberley.

Art, music, film and literature

Notable artists from Kimberley include William Timlin and Walter Westbrook, while an artist noted for his depiction of Kimberley was Philip Bawcombe.

Writers from the city or with strong Kimberley links include Diane Awerbuck, Benjamin Bennett, Lawrence Green, Dorian Haarhoff, Dan Jacobson, E P Lekhela, Z.K. Matthews, Sarah Gertrude Millin, Sol Plaatje, Frank Templeton Prince, Olive Schreiner, A.H.M. Scholtz.

A notable reggae and rhythm and blues musician from Kimberley is Dr Victor.[53]

Museums, monuments and memorials

- The Big Hole, previously known as the Kimberley Mine Museum, is a recreated townscape and museum, with Big Hole viewing platform and other features, situated next to the Kimberley Mine ("Big Hole"). It houses a rich collection of artefacts and information from the early days of the city.[54]

- The McGregor Museum, which celebrated its centennial in 2007, curates and studies major research collections and information about the history and ecology of the Northern Cape, which are reflected in displays at the museum's headquarters at the Sanatorium in Belgravia and nine branch museums.

- The William Humphreys Art Gallery.[55]

- The Kimberley Africana Library.

- Dunluce and Rudd House Museums.

- Pioneers of Aviation Museum: In 1913, South Africa's first flying school opened at Kimberley and started training the pilots of the South African Aviation Corps, later to become the South African Air Force.[56] The museum is located on the site of that flying school and houses a replica of a Compton Paterson biplane, one of the first aircraft to be used for flight training. The first female on the African continent to receive her pilot's license, Ann Maria Bocciarelli, was trained at this facility.[57]

- Robert Sobukwe's Law Office

- The Sol Plaatje Museum is located in the house where Sol Plaatje lived and wrote Mhudi.

- Transport Spoornet Museum

- Clyde N. Terry Hall of Militaria

- Freddie Tate Museum

- A heritage tramway was opened in 1985, putting one of Kimberley's historic trams back on the rails.

- On the outskirts of Kimberley, on the Barkly West Road, the Wildebeest Kuil Rock Art Centre, as well as Nooitgedacht Glacial Pavements. To the south of the city, the Magersfontein Battlefield Museum (see Battle of Magersfontein), while blockhouses can be seen at Modder River.

Memorials include:

- The Miners' Memorial, also known as the Diggers' Fountain, located in the Oppenheimer Gardens and designed by Herman Wald. It was built in honour of all the miners of Kimberley. The memorial consists of five life-sized diggers lifting a diamond sieve.

- The Honoured Dead Memorial commemorates those who died defending the city during the Siege of Kimberley in the Anglo-Boer War.

- The Cenotaph erected originally to commemorate the fallen of World War I, with plaques added in memory of fallen Kimberley volunteers in World War II. There is a memorial dedicated to the Kimberley Cape Coloured Corps who died in the Battle of Square Hill during World War I. Consisting of a gun captured at the battle, it originally stood in Victoria Crescent, Malay Camp, but, post-1994, was moved to the Cenotaph.

- The Concentration Camp Memorial remembers those who were interned in the Kimberley concentration camp during the Second Boer War, and is located in front of the Dutch Reformed Mother Church.

- The Henrietta Stockdale statue, by Jack Penn, commemorates the Anglican nun, Sister Henrietta CSM&AA (her reinterred remains are buried alongside), who petitioned the Cape Parliament to pass a law recognizing nursing as a profession and requiring compulsory state registration of nurses - a first in the world.

- The statue of Frances Baard was unveiled by Premier Hazel Jenkins on Women's Day, 9 August 2009.

- The Sol Plaatje Statue was unveiled by South African President Jacob Zuma on 9 January 2010, the 98th anniversary of the founding of the African National Congress. Sculpted by Johan Moolman, it is at the Civic Centre, formerly the Malay Camp, and situated approximately where Plaatje had his printing press in 1910-13.[58]

- Burger Monument near Magersfontein Battlefield

- Cape Police Memorial

- Mayibuye Memorial

- Rhodes equestrian statue

- Malay Camp Memorial

Architecture

- Alexander McGregor Memorial Museum (1907)

- De Beers Head Office

- Dunluce (Late Victorian)

- Harry Oppenheimer House (mid-1970s)

- Honoured Dead Memorial

- Kimberley Africana Library

- Kimberley City Hall (Neo-classical)

- Kimberley Club

- Kimberley Regiment Drill Hall (1892)

- Kimberley Sanatorium (McGregor Museum) (1897)

- Kimberley Undenominational Schools

- Masonic Temple

- Northern Cape Provincial Legislature

- Old School of Mines (Late Victorian)

- Rudd House (The Bungalow)

- The Lodge (Duggan-Cronin Gallery)

Notable religious buildings

- Dutch Reformed Mother Church Newton is a good example of Stucco architecture in Kimberley. It was declared a National Monument in 1976, now a Provincial Heritage Site.[59]

- Kimberley's older Mosques were replaced by newer ones as a result of the Group Areas Act and the forced resettlement of the city's Muslim communities.

- Kimberley Seventh-day Adventist Church is a small L shaped corrugated-iron building and is considered the mother church of Seventh-day Adventists in South Africa. It was declared a National Monument in 1967, now a Provincial Heritage Site.[60]

- St Cyprian's Anglican Cathedral was designed by Arthur Lindley of the firm of Greatbatch, the building of the nave being completed in 1908. The remainder of the cathedral was completed in stages, partly under guidance of William M. Timlin (also of the firm of Greatbatch). In 1926 the Chancel was dedicated (and as a World War I memorial); in 1936 the Lady Chapel, Vestry & new organ were added; and in 1961, the tower (a World War II memorial). The cathedral contains notable stained glass windows including works by the Pretoria artist Leo Theron.

- St Mary's Roman Catholic Cathedral.

- Synagogue in the Byzantine style designed by D.W. Greatbatch, and based on the synagogue in Florence, Italy.

Media

The city is served by both print media and community radio stations.

Newspapers

The earliest newspaper here was the Diamond Field, published initially at Pniel on 15 October 1870. Other early papers with the Diamond News and the Independent. The Diamond Fields Advertiser is Kimberley's current daily newspaper, published since 23 March 1878.[61][62] The Volksblad, with a free local supplement called Noordkaap, is read by Afrikaans-speaking readers.

Radio

Two community radio stations were founded in the 1990s:

- Radio Teemaneng

- XKfm which is based in the !Xun and Khwe settlement of Platfontein outside Kimberley and broadcasts in the two KhoeSan languages spoken at Platfontein (!Xun and Khwedam)

Sport

Cricket

Kimberley has contributed to much of cricket's history having supplied several international players. There was Nipper Nickelson, Xenophon Balaskas born in Kimberley to Greek parents and Ken Viljoen, Ronnie Draper and in more recent times Pat Symcox and the Proteas coach Mickey Arthur.

Kimberley hosted a match from the 2003 ICC Cricket World Cup. Elsie McDonald was a Springbok bowler.

Rugby

Frank Dobbin known as Uncle Dobbin was a member of Paul Roos' original Springboks in the tour to the British Isles in 1906/1907. His memory lives in his old colonial-style home in Roper street, bearing a simple brass plaque with the name 'Dobbin'. Later Springboks to wear green and gold included Ian Kirkpatrick, Tommy Bedford and Gawie Visagie, brother of Ammosal-based Springbok flyhalf Piet Visagie.

Kimberley is home to the GWK Griquas rugby team, which has won the Currie Cup three times in 1899, 1911 and 1970.

Football

Richard Henyekane, South African footballer, came from Kimberley.

Jimmy Tau is from Kimberley, born and grew up in the dusty streets of No. 5 in Makapane Street, Vergenoeg. Joseph Henyekane younger brother to Richard Henyekane played for Golden Arrows [63]

Swimming

Karen Muir, born in Kimberley, became in 1965 the youngest person to break a world record in any sport. This age group record stands to this day.[64] She set it in August 1965 at the junior world champions in Blackpool, England in the 110 metres (360 ft) backstroke at the age of 12. She went on to break many more world records but was denied a role in world swimming when she lost the opportunity to represent her country at the 1968 Olympic games in Mexico City as a result of South Africa being excluded due to its racial apartheid policies. Kimberley also saw a world record broken in the municipal pool which now bears Karen Muir's name. It was Johannesburg's Anne Fairlie who beat Karen Muir and Frances Kikki Caron in world record breaking time.

Charl Bouwer, the paralympic swimmer from South Africa who won gold in the 50m freestyle at the 2012 Summer Paralympics in London, was born in Kimberley.[65]

Athletics

Bevil Rudd, Olympic medallist.

Cycling

Prominent cyclists have been Joe Billet, Steve Viljoen and Eddie Fortune.Joe Billet qualify for the 1968 Olympics to be held in Mexico. Joe was the backbone of cycling in Kimberley for years to come inspired cyclists like the Hendriks brothers and Hennie champ Schoeman

Skateboarding

The first Maloof Money Cup World Skateboarding Championships were held in Kimberley in September 2011 and again in 2012. When the Maloof family sponsorship ended in 2013 the event became known as the Kimberley Diamond Cup.[66]

Sporting facilities

- ABSA Park

- De Beers Diamond Oval*

- Flamingo Park (Thoroughbred horse racing)

- Galeshewe Stadium

- Karen Muir Swimming Pool

Quotations

"Kimberley has had a profound effect on the course of history in Southern Africa. The discovery of diamonds there, more than a century ago, proved to be the first step in the transformation of South Africa from an agricultural into an industrial country. When gold and other minerals were later discovered to the north, there were already Kimberley men of vision and enterprise with the capital and technology to develop the new resources." - H.F. Oppenheimer, 1976. Foreword to Brian Roberts’ book, Kimberley, turbulent city.

Anthony Trollope visited Kimberley in 1877 and was notoriously put off by the heat, enervating and hideous, while the dust and the flies of the early mining town almost drove him mad: "I sometimes thought that the people of Kimberley were proud of their flies and their dust." Of the townscape, largely built of sun-dried brick, and of plank and canvas and corrugated iron sheets brought up by ox-wagon from the coast, he remarked: "In Kimberley there are two buildings with a storey above the ground, and one of these is in the square: this is its only magnificence. There is no pavement. The roadway is all dust and holes. There is a market place in the midst which certainly is not magnificent. Around are the corrugated iron shops of the ordinary dealers in provisions. An uglier place I do not know how to imagine."[67]

A.H.J. Bourne, a former headmaster of Kimberley Boys' High School, returned to the city in 1937, observing that: "The history of Kimberley would appear remarkable to any stranger who could not fail to think that some supermind was behind its destinies. In so short a time it has grown from bare veld."[68]

In the early 1990s writer Dan Jacobson returned to Kimberley, where he had grown up in the 1930s, giving a sense of how things had changed: "The people I had known had vanished; so had their language. That contributed to my ghostlike state. In my earliest years the whites of Kimberley spoke English only; Afrikaans was the tongue of the Cape Coloured people ... Now I was addressed in Afrikaans everywhere I went, by white, black, and Coloured alike".[69]

Kimberley dull? – asked virtualtourist reviewer Catherine Reichardt: "Happily, the answer is a resounding 'No', provided that you have a passion for history - in which case Kimberley has it in spades, and you'll probably need to overnight to fully appreciate its attractions and charms. In many ways, exploring Kimberley and its heritage is like experiencing South African history in microcosm."[70]

Kimberley Miscellany

- The Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) is an initiative for preventing trade in "conflict diamonds" used to finance the undermining of legitimate governments. It was founded in 2003, following a May 2000 meeting of Southern African diamond-producing states in Kimberley. A tenth anniversary meeting of the Kimberley Process was held at the Mittah Seperepere Convention Centre, Kimberley, on 4--7 June 2013, bringing together representatives of Governments, the diamond industry and civil society. A commemorative event was held at the Kimberley Tabernacle, the venue for the original meeting of the KPCS, where 23 individuals present at the very first meeting were honoured for their involvement. South African Minister of Mineral Resources, Susan Shabangu, addressed the closing session, noting the role of the KPCS in minimising "blood diamond" trade, as well as its "significant developmental impact in improving the lives of people dependent on the trade in diamonds."[71]

- The Kimberley Declaration is a statement, inter alia on respect, promotion and protection of traditional knowledge systems, published by the Indigenous Peoples Council on Biocolonialism, on behalf of the International Indigenous Peoples Summit on Sustainable Development, Khoi-San Territory, Kimberley, South Africa, 20–23 August 2002[72]

See also

- Apostolic Vicariate of Kimberley in Orange for the region's Catholic missionary history

- Kimberley Process

- List of heritage sites in Kimberley

- Mokala National Park

- People of Kimberley

- Trams in Kimberley, Northern Cape

References

- 1 2 3 4 Sum of the Main Places Roodepan, Galeshewe and Kimberley from Census 2011.

- ↑ http://afkinsider.com/35226/17-things-didnt-realize-invented-by-south-africans/17/

- 1 2 Martin Meredith (2007). Diamonds, Gold, and War: The British, the Boers, and the Making of South Africa. New York: Public affairs. p. 16. ISBN 1-58648-473-7.

- ↑ Roberts, Brian (1972). The Diamond Magnates. London: Hamilton. p. 5. ISBN 0241021774.

- ↑ Wilson, A.N. (1982). Diamonds : from birth to eternity. Santa Monica, California: Gemological Institute of America. p. 135. ISBN 0873110102.

- ↑ Chilvers, Henry (1939). The Story of De Beers. Cassell. pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Roberts, Brian. 1976. Kimberley, turbulent city. Cape Town: David Philip pp 45-49

- ↑ Ralph, Julia (1900). Towards Pretoria; a record of the war between Briton and Boer, to the relief of Kimberley. Frederick A. Stokes company.

- 1 2 Roberts, Brian. 1976. Kimberley, turbulent city. Cape Town: David Philip, p 115

- ↑ Roberts, Brian. 1976. Kimberley, turbulent city. Cape Town: David Philip, p 116

- ↑ Select Constitutional Documents Illustrating South African History 1795-1910. Routledge and Sons. 1918. p. 66.

- ↑ Roberts, Brian. 1976. Kimberley, turbulent city. Cape Town: David Philip, p. 155.

- ↑ Hannatjie van der Merwe (20 May 2005). "Big Hole loses claim to fame". News24. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ Bid to plug Big Hole worldwide, News24

- ↑ UNESCO World Heritage Tentative Lists: Kimberley Mines and Associated Early Industries

- ↑ Martin Meredith, Diamonds, Gold, and War: The British, the Boers, and the Making of South Africa, (New York, Public Affairs, 2007):34

- ↑ "Anglo American: De Beers investor presentation" (PDF). Anglo American. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ↑ John Hays Hammond (1974). The Autobiography of John Hays Hammond. Ayer Publishing. p. 205. ISBN 0-405-05913-2.

- ↑ Meredith, 36.

- ↑ Martin Meredith, Diamonds, Gold, and War, (New York, Public Affairs, 2007): 34

- ↑ Sessional Papers By Great Britain Parliament. House of Commons. 1902.

- 1 2 3 Roberts, Brian. 1976. Kimberley, turbulent city. Cape Town: David Philip

- ↑ Apartheid and the archbishop: the life and times of Geoffrey Clayton, Archbishop of Cape Town Paton, A: New York, Scribner 1974 ISBN 0-684-13713-5

- ↑ Review of Paton's Apartheid and the Archbishop by Edgar Brookes

- ↑ Mayibuye Uprising of 8 November 1952 by Johlene May

- ↑ Indian Opinion 23 Jan 1953 – Apartheid policy responsible for riots

- ↑ e.g. Shillington, K. 1985. The colonisation of the Southern Tswana. Johannesburg: Ravan Press

- ↑ 'Local and General' in The Diamond News and Griqualand West Government Gazette (16 May 1878).

- ↑ The arms are depicted on an illuminated address presented to governor Sir Bartle Frere in 1879 and one presented to governor Sir Henry Brougham Loch in 1890.

- ↑ Cape of Good Hope Official Gazette 3270 (18 December 1964).

- 1 2 http://www.national.archsrch.gov.za

- ↑ The arms were depicted on a cigarette card issued in 1931.

- 1 2 Brian Roberts (1976). Kimberley. D. Philip, Historical Society of Kimberley and the Northern Cape. ISBN 0-949968-62-5.

- ↑ Morris, Michael; Linnegar, John (2004). Every Step of the Way. Human Sciences Research Council. ISBN 0-7969-2061-3.

- ↑ Christie, Renfrew (1984). Electricity, Industry and Class in South Africa. London: The Macmillan Press Ltd. pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Conradie, S. R.; Messerschmidt, L. J. M. (2000). A Symphony of Power: The Eskom Story. Johannesburg: Chris van Rensburg Publications. p. 13.

- ↑ Becker, Dave (1991). On Wings of Eagles: South Africa's Military Aviation History (1 ed.). Durban: Walker-Ramus Trading Co. p. 9. ISBN 0-947478-47-7.

- ↑ Burman, Jose (1984). Early Railways at the Cape. Cape Town. Human & Rousseau, p.95. ISBN 0-7981-1760-5

- ↑ Worger, W.H. 1987. South Africa’s City of Diamonds. Mine Workers and Monopoly Capitalism in Kimberley, 1867–1895. London: Yale University Press

- ↑ e.g. Holub, Emil (1881). Seven Years in South Africa: Travels, Researches and Hunting Adventures, Between the Diamond-Fields and the Zambesi (1872–79)

- ↑ "Kimberley Climate Normals 1961−1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- ↑ "Klimatafel von Kimberley, Provinz Northern Cape / Südafrika" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ↑ "Station Kimberley" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- 1 2 "Climate data for Kimberley". South African Weather Service. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- ↑ "Main Place Kimberley". Census 2011.

- ↑ "Main Place Galeshewe". Census 2011.

- ↑ "Main Place Roodepan". Census 2011.

- ↑ Wildenboer, N. 2013. Expert confirms Kamfers Dam birds' cause of death. Diamond Fields Advertiser 13 Dec 2013 p 11

- ↑ Address by the President of South Africa during the announcement of new Interim Councils and names of the New Universities

- ↑ Government Notice 1031 gazetted on 7 Dec 2012, as amended by Government Notice 1073, gazetted on 14 Dec 2012

- ↑ Northern Cape’s first university to open in 2014, Timeslive 21 Mar 2013

- ↑ New Universities Project Management Team: Academic Planning

- ↑ Dr Victor: biography Accessed 9 June 2013

- ↑ The Big Hole Kimberley - Diamonds and Destiny

- ↑ William Humphreys Art Gallery

- ↑ Tidy, Major D.P. "They Mounted up as Eagles (A brief tribute to the South African Air Force)". 5 (6). The South African Military History Society. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009.

- ↑ "The History of Aviation in South Africa". South African Power Flying Association. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ↑ Plaatje Statue unveiled, Diamond Fields Advertiser, 11 Jan 2010, p 6. (Reports in the Sunday Argus and Independent On Line [10 January 2010 at 12:42PM] incorrectly state that the unveiling of this statue took place in Cape Town)

- ↑ "Dutch Reformed Mother Church Newton". South African Heritage Resources Agency. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ↑ "First Seventh Day Adventist Church Blacking Street Kimberley". South African Heritage Resources Agency. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ↑ du Toit, Anneke (10 September 2008). "A lot of news, a lot of newspapers". Volksblad. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Brian Roberts. 1976. Kimberley, turbulent city, p 173

- ↑ SAFA

- ↑ Swimming in South Africa. Last accessed 2008-04-12

- ↑ Charl Bouwer swem SA se negende Paralimpiese medalja los: 2 Sep 2012

- ↑ http://www.kimberleydiamondcup.com

- ↑ cited by Roberts, Brian. 1976. Kimberley, turbulent city, p 159-160

- ↑ cited in L. Moult. 1987. KHStory, p 126

- ↑ Dan Jacobson, The Electronic Elephant: A Southern African Journey, London: Penguin, 1994, p 73

- ↑ Catherine Reichardt on A cracking day out in Kimberley.

- ↑ Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) Intersessional Meeting ends with review on processes and functions Accessed 7 June 2013.

- ↑ Kimberley Declaration Accessed on 7 June 2013

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kimberley (Northern Cape). |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kimberley (South Africa). |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Kimberley. |

- The Kimberley City Portal - An on-line directory for tourists, travellers and residents of Kimberley. Detailed listings of business, attractions, activities and events with photos, contact information and geo-locations.

- Kimberley, turbulent city by Brian Roberts (1976, published by David Phillip & Historical Society of Kimberley and the Northern Cape)

- "Diamond Mines of South Africa" by Gardner Williams (General manager De Beers), Chapter 15 (25 page history + images).

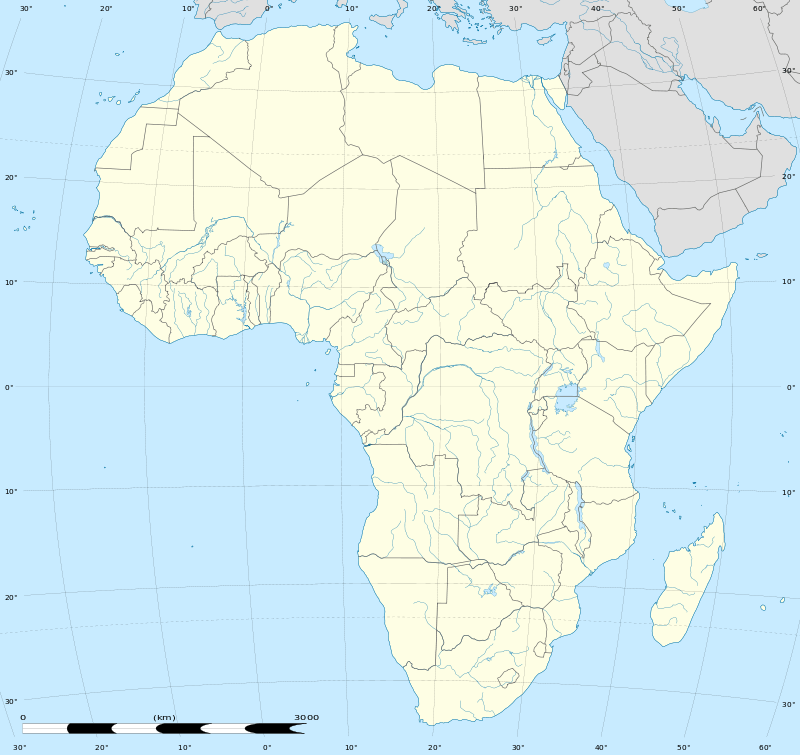

Geographic Location

|

Barkly West | Warrenton | Boshof |  |

| Campbell | |

Bloemfontein | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Douglas | Ritchie | Koffiefontein |

.svg.png)