Muggiaea atlantica

| Muggiaea atlantica | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Cnidaria |

| Class: | Hydrozoa |

| Order: | Siphonophorae |

| Suborder: | Calycophorae |

| Family: | Diphyidae |

| Genus: | Muggiaea |

| Species: | M. atlantica |

| Binomial name | |

| Muggiaea atlantica Cunningham, 1892[1] | |

Muggiaea atlantica is a species of small hydrozoan jellyfish, a siphonophore in the family Diphyidae. It is a cosmopolitan species occurring in inshore waters of many of the world's oceans, and it has colonised new areas such as the North Sea and the Adriatic Sea. It is subject to large population swings, and has been held responsible for the death of farmed salmon in Norway. The species was first described by J.T. Cunningham in 1892 from a specimen obtained at Plymouth, England.

Description

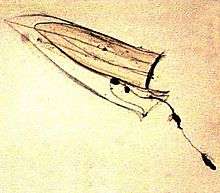

Muggiaea atlantica is a small colonial siphonophore, but one of the two nectophores (swimming bells) is undeveloped. The remaining nectophore grows to a length of about 7 mm (0.3 in). It is translucent and has five straight, longitudinal ridges, some of which may form a keel. The hydroecium (ventral cavity) is about one third of the length of the nectophore, and the long slender somatocyst (extension of the gastrovascular system) reaches the apex of the nectosac (central cavity) and sometimes contains oil droplets.[2][3] The eudoxid (reproductive stage) soon becomes detached. It has a cone-shaped, asymmetric bract with a wide flanged suture running from apex to base. The right edge of the bract is curved while the left edge is truncated horizontally. The lower surface has a small cavity in which the somatocyst is situated.[4]

Distribution and habitat

Muggiaea atlantica is a neritic species that forms part of the zooplankton, and is found in the upper hundred metres of inshore temperate and subtropical waters worldwide. It is present in the Atlantic Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean. It is a common siphonophore and probably more abundant than any other species of siphonophore in nearshore habitats. Its abundance is seasonal, and in parts of the northern hemisphere it has population peaks in May/June and again in September/November.[5] In the western English Channel it occurred sporadically before the 1960s but after 1968 it became resident. Its seasonal distribution and abundance seem to be associated with sea temperature changes and the availability of food.[6] It appeared in the southern Adriatic Sea for the first time in the mid 1990s and became increasingly common there. It was detected in the marine lakes on the island of Mljet in southern Croatia in 2001, and seems to have displaced Muggiaea kochii in the Great Lake there. It is hypothesized that the cold winter of 2000/2001 favoured the more cold-tolerant M. atlantica over the warm-temperate M. kochii.[7]

Ecology

Muggiaea atlantica swims in an arc, propelled by pulsations of its bell, and then remains stationary for several minutes.[8] It feeds almost entirely on copepods, consuming an estimated five to ten prey items daily, mostly during the night.[9] In the eastern Pacific it is eaten by predatory fish such as the blue rockfish (Sebastes mystinus), and by the floating sea snail Carinaria cristata.[5]

Reproduction in this species is by an alternation of generations between an asexual polygastric animal (bearing both asexual and reproductive elements) and the sexual eudoxid stage which becomes detached from the nectophore. The generation time is short and under favourable conditions, numbers can build up rapidly.[6]

A population explosion of M. atlantica in the North Sea in 1989 caused major changes in the composition of the community. The siphonophere was present at densities of five hundred per cubic metre and this depleted the copepods normally present. This resulted in a reduction in the grazing pressure on the phytoplankton and an increase in their growth, causing an algal bloom and other cascading ecosystem effects.[10]

The aquaculture industry in Norway suffered a setback in 2007 when more than 100,000 caged salmon were killed by a bloom of M. atlantica, present at a concentration of 2,000 per cubic metre in coastal waters.[8] This siphonophore is also thought to have been involved in the loss of a million farmed salmon in Ireland in 2003.[11]

References

- ↑ Schuchert, Peter (2015). "Muggiaea atlantica Cunningham, 1892". World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved 2015-04-14.

- ↑ van Couwelaar, M. "Muggiaea atlantica". Zooplankton and Micronekton of the North Sea. Marine Species Identification Portal. Retrieved 2015-04-14.

- ↑ C. D. Todd; M. S. Laverack; Geoff Boxshall (1996). Coastal Marine Zooplankton: A Practical Manual for Students. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-521-55533-3.

- ↑ Russell, F.S. (1938). "On the Development of Muggiaea atlantica Cunningham". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 22 (2): 441–446. doi:10.1017/S0025315400012340.

- 1 2 Mapstone, Gillian M.; Arai, Mary N. (2009). Siphonophora (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa) of Canadian Pacific Waters. NRC Research Press. pp. 23–33. ISBN 978-0-660-19843-9.

- 1 2 Blackett, Michael; Licandro, Priscilla; Coombs, Steve H.; Lucas, Cathy H. (2014). "Long-term variability of the siphonophores Muggiaea atlantica and M. kochi in the Western English Channel". Progress in Oceanography. 128: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.pocean.2014.07.004.

- ↑ Batistić, Mirna; Lučić, Davor; Carić, Marina; Garić, Rade; Licandro, Priscilla; Jasprica, Nenad (2013). "Did the alien calycophoran Muggiaea atlantica outcompete its native congeneric M. kochi in the marine lakes of Mljet Island (Croatia)?". Marine Ecology. 34 (s1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/maec.12021.

- 1 2 Pitt, Kylie A.; Lucas, Cathy H. (2013). Jellyfish Blooms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 121–134. ISBN 978-94-007-7015-7.

- ↑ Purcell, Jennifer E. (1982). "Feeding and growth of the siphonophore Muggiaea atlantica (Cunningham 1893)". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 62 (1): 39–54. doi:10.1016/0022-0981(82)90215-5.

- ↑ Greve, Wulf (1994). "The 1989 German Bight invasion of Muggiaea atlantica". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 51 (4): 355–358. doi:10.1006/jmsc.1994.1037.

- ↑ Woo, Patrick T. K.; Gregory, David W. Bruno (2014). Diseases and Disorders of Finfish in Cage Culture, 2nd Edition. CABI. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-78064-207-9.