Morchella rufobrunnea

| Morchella rufobrunnea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Pezizomycetes |

| Order: | Pezizales |

| Family: | Morchellaceae |

| Genus: | Morchella |

| Species: | M. rufobrunnea |

| Binomial name | |

| Morchella rufobrunnea Guzmán & F.Tapia (1998) | |

| Morchella rufobrunnea | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| smooth hymenium | |

|

cap is conical or ovate | |

| stipe is bare | |

|

spore print is cream to yellow | |

| ecology is saprotrophic | |

| edibility: choice | |

Morchella rufobrunnea, commonly known as the blushing morel, is a species of ascomycete fungus in the family Morchellaceae. A choice edible species, the fungus was originally described as new to science in 1998 by mycologists Gastón Guzmán and Fidel Tapia from collections made in Veracruz, Mexico. Its distribution was later revealed to be far more widespread after several DNA studies suggested that it is common in the West Coast of the United States, Israel, Australia, and Cyprus.

M. rufobrunnea grows in disturbed soil or in woodchips used in landscaping, suggesting a saprophytic mode of nutrition. Reports from the Mediterranean under olive trees (Olea europaea), however, suggest the fungus may also be able to form facultative tree associations. Young fruit bodies have conical, grayish caps covered with pale ridges and dark pits; mature specimens are yellowish to ochraceous-buff. The surface of the fruit body often bruises brownish orange to pinkish where it has been touched, a characteristic for which the fungus is named. Mature fruit bodies grow to a height of 9.0–15.5 cm (3.5–6.1 in). M. rufobrunnea differs from other Morchella species by its urban or suburban habitat preferences, in the color and form of the fruit body, the lack of a sinus at the attachment of the cap with the stipe, the length of the pits on the surface, and the bruising reaction. A process to cultivate morels now known to be M. rufobrunnea was described and patented in the 1980s.

Taxonomy

The first scientifically described specimens of Morchella rufobrunnea were collected in June 1996 from the Ecological Institute of Xalapa and other regions in the southern Mexican municipality of Xalapa, which are characterized by a subtropical climate. The type locality is a mesophytic forest containing oak, sweetgum, Clethra and alder at an altitude of 1,350 m (4,430 ft).[1] In a 2008 study, Michael Kuo determined that the "winter fruiting yellow morel"—erroneously referred to as Morchella deliciosa—found in landscaping sites in the western United States was the same species as M. rufobrunnea. According to Kuo,[2] David Arora depicts this species in his popular 1986 work Mushrooms Demystified, describing it as a "coastal Californian form of Morchella deliciosa growing in gardens and other suburban habitats".[3] Kuo suggests that M. rufobrunnea is the correct name for the M. deliciosa used by western American authors.[4] Other North American morels formerly classified as deliciosa have since been recategorized into two distinct species, Morchella diminutiva and M. sceptriformis (=M. virginiana).[5]

Molecular analysis of nucleic acid sequences from the internal transcribed spacer and elongation factor EF-1α regions suggests that the genus Morchella can be divided into three lineages. M. rufobrunnea belongs to a lineage that is basal to the esculenta clade ("yellow morels"), and the elata clade ("black morels").[6][7] This phylogenetic placement implies that it has existed in its current form since the Cretaceous era (roughly 145 to 66 million years ago), and all known morel species evolved from a similar ancestor.[8] M. rufobrunnea is genetically closer to the yellow morels than the black morels.[7] M. anatolica, described from Turkey in 2012, is a closely related sister species.[9]

The specific epithet rufobrunnea derives from the Latin roots ruf- (rufuous, reddish) and brunne- (brown).[3] Vernacular names used for the fungus include "western white morel",[10] "blushing morel",[4] and—accounting for the existence of subtropical species in the "blushing clade"—"red-brown blushing morel".[11]

Description

Fruit bodies of M. rufobrunnea can reach 6.0–21.0 cm (2.4–8.3 in) tall, although most are typically found in a narrower range, 9.0–15.5 cm (3.5–6.1 in). The conical to roughly cylindrical hymenophore (cap) is typically 6.0–8.5 cm (2.4–3.3 in) high by 3.0–4.5 cm (1.2–1.8 in) wide. Its surface is covered with longitudinal anastomosed ridges and crosswise veins that form broad, angular, elongated pits. Young fruit bodies are typically dark grey with sharply contrasting beige or buff ridges, while mature specimens fade to ochraceous-buff. The cylindrical stipe is often strongly wrinkled, enlarged at the base and measures 30–70 cm (12–28 in) by 1–2.5 cm (0.4–1.0 in) thick. It is typically covered with a dark brown to greyish pruinescence, often fading at maturity, a useful character to discriminate it from similar species, such as M. tridentina or M. sceptriformis. The stipe and hymenophore often exhibit ochraceous, orange or reddish stains, although this feature is neither constant nor exclusive to M. rufobrunnea and can be seen in a number of Morchella species, such as Morchella tridentina (=Morchella frustrata), M. esculenta, M. guatemalensis, the recently described M. fluvialis (Clowez et al. 2014), and most likely M. anatolica.[12]

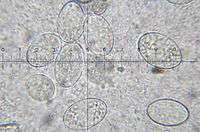

In deposit, the spores are pale orange to yellowish orange. Ascospores are egg-shaped, measuring 20–24 by 14–16 µm when mature, but smaller (14.5–19 by 9–10 µm) in immature fruit bodies. They are thin-walled, hyaline (translucent), and inamyloid. The cylindrical asci (spore-bearing cells) are 300–360 by 16–20 µm with walls up to 1.5 µm thick. Paraphyses measure 90–184 by 10–18.5 µm (6–9 µm thick if immature); they are hyaline, have a septum at the base, and comprise either one or two cells. The flesh is made of thin-walled, hyaline hyphae measuring 3–9 µm wide.[1]

Morchella rubobrunnea is an edible fungus;[13] it has been described variously as "one of the tastiest members of the morel family",[10] and alternately as "bland in comparison to other morel species".[14] Individual specimens over 1 pound (0.45 kg) have been reported.[10]

Similar species

Morchella tridentina (=Morchella frustrata) is also rufescent and very similar to M. rufobrunnea. It is found in mountainous forests and maquis and forms a marked sinus at the attachment of the cap with the stem, which is pure white. At maturity, it develops more or less parallel, ladderlike interconnecting ridges. Microscopically, it often has moniliform paraphyses with septa extending in the upper half and has more regularly cylindrical or clavate 'hairs' on the stem, up to 100 μm long.[12] M. guatemalensis, found in Central America, has a color ranging from yellow to yellowish-orange, but never grey, and it has a more distinct reddish to wine red bruising reaction. Microscopically, it has smaller paraphyses, measuring 56–103 by 6.5–13 µm. The New Guinean species M. rigidoides has smaller fruit bodies that are pale ochre to yellow, without any grey. Its pits are less elongated than those of M. rufobrunnea, and it has wider paraphyses, up to 30 µm.[1]

Morchella americana (=M. esculentoides), is widely distributed in North America, north of Mexico and has similar colours to mature fruit bodies of M. rufobrunnea, but lacks the bruising reaction. M. diminutiva, found in hardwood forests of eastern North America, has a smaller fruit body than M. rufobrunnea, up to 9.4 cm (3.7 in) tall and up to 2.7 cm (1.1 in) wide at its widest point. Morchella sceptriformis (=Morchella virginiana) is found in riparian and upland ecosystems from Virginia to northern Mississippi, usually in association with the American tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera).[5]

Habitat and distribution

A predominantly saprophytic species, Morchella rufobrunnea fruit bodies grow singly or in clusters in disturbed soil or woodchips used in landscaping. Large numbers can appear the year after wood mulch has been spread on the ground.[13] Typical disturbed habitats include fire pits, near compost piles, logging roads, and dirt basements.[15] Fruiting usually occurs in the spring, although fruit bodies can be found in these habitats most of the year. Other preferred habitats include steep slopes and plateaus, and old-growth conifer forests.[10] In Cyprus, the fungus is frequently reported from coastal, urban and suburban areas under olive trees (Olea europaea).[12][16]

Morchella rufobrunnea ranges from Mexico through California and Oregon in the United States.[2] It has also been introduced to central Michigan from California.[5] It is one of seven Morchella species that have been recorded in Mexico.[1] In 2009, Israeli researchers used molecular genetics to confirm the identity of the species in northern Israel, where it was found growing in gravelly disturbed soil near a newly paved path at the edge of a grove. This was the first documented appearance of the fungus outside the American continent. Unlike North American populations that typically fruit for only a few weeks in spring, the Israeli populations have a long-season ecotype, fruiting from early November to late May (winter and spring). This period corresponds to the rainy season in Israel (October to May), with low to moderate temperatures ranging from 15–28 °C (59–82 °F) during the day and 5–15 °C (41–59 °F) at night.[17]

Cultivation

Morchella rufobrunnea is the morel that is cultivated commercially per US patents 4594809[18] and 4757640.[5][19] This process was developed in 1982 by Ronald Ower with what he thought was Morchella esculenta;[18] M. rufobrunnea had not yet been described. The cultivation protocol consists of preparing a spawn culture that is mixed with nutrient-poor soil. This mixture is laid on nutrient-rich soil and kept sufficiently moist until fruiting. In the nutrient-poor substrate, the fungus forms sclerotia—hardened masses of mycelia that serve as food reserves. Under appropriate environmental conditions, these sclerotia grow into morels.[20]

The fruit bodies of Morchella rufobrunnea have been cultivated under controlled conditions in laboratory-scale experiments. Primordia, which are tiny nodules from which fruit bodies develop, appeared two to four weeks after the first watering of pre-grown sclerotia incubated at a temperature of 16 to 22 °C (61 to 72 °F) and 90% humidity. Mature fruit bodies grew to 7 to 15 cm (3 to 6 in) long.[21]

The early stages of fruit body development can be divided into four discrete stages. In the first, disk-shaped knots measuring 0.5–1.5 mm appear on the surface of the substrate. As the knot expands in size, a primordial stipe emerges from its center. The stipe lengthens, orients upward, and two types of hyphal elements develop: long, straight and smooth basal hairy hyphae and short stipe hyphae, some of which are inflated and project out of a cohesive layer of tightly packed hyphal elements. In the final stage, which occurs when the stipe is 2–3 mm long, immature caps appear that have ridges and pits with distinct paraphyses. Extracellular mucilage that covers the ridge layer imparts shape and rigidity to the tissue and probably protects it against dehydration.[22]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Guzmán G, Tapia F (1998). "The known morels in Mexico, a description of a new blushing species, Morchella rufobrunnea, and new data on M. guatemalensis". Mycologia. 90 (4): 705–14. doi:10.2307/3761230. JSTOR 3761230.

- 1 2 Kuo M. (2008). "Morchella tomentosa, a new species from western North America, and notes on M. rufobrunnea" (PDF). Mycotaxon. 105: 441–6.

- 1 2 Arora D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: A Comprehensive Guide to the Fleshy Fungi. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 978-0-89815-169-5.

- 1 2 Kuo M. (2005). Morels. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-472-03036-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Kuo M, Dewsbury DR, O'Donnell K, Carter MC, Rehner SA, Moore JD, Moncalvo JM, Canfield SA, Stephenson SL, Methven AS, Volk TJ (2012). "Taxonomic revision of true morels (Morchella) in Canada and the United States". Mycologia. 104 (5): 1159–77. doi:10.3852/11-375. PMID 22495449.

- ↑ Kanwal HK, Acharya K, Ramesh G, Reddy MS (2011). "Molecular characterization of Morchella species from the Western Himalayan region of India". Current Microbiology. 62 (4): 1245–52. doi:10.1007/s00284-010-9849-1. PMID 21188589.

- 1 2 Barseghyan GS, Kosakyan A, Isikhuemhen OS, Didukh M, Wasser SP. "Phylogenetic analysis within genera Morchella (Ascomycota, Pezizales) and Macrolepiota (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) inferred from nrDNA ITS and EF-1α sequences". In Misra JK, Tewari JP, Desmukh SK. Systematics and Evolution of Fungi. Progress in Mycological Research. 2. Boca Raton, Florida: Science Publishers. pp. 159–205. ISBN 978-1-57808-723-5.

- ↑ O'Donnell K, Rooney AP, Mills GL, Kuo M, Weber NS, Rehner SA (2011). "Phylogeny and historical biogeography of true morels (Morchella) reveals an early Cretaceous origin and high continental endemism and provincialism in the Holarctic" (PDF). Fungal Genetics and Biology. 48 (3): 252–65. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2010.09.006. PMID 20888422.

- ↑ Taşkın H, Büyükalaca S, Hansen K, O'Donnell K (2012). "Multilocus phylogenetic analysis of true morels (Morchella) reveals high levels of endemics in Turkey relative to other regions of Europe". Mycologia. 104 (2): 446–61. doi:10.3852/11-180. PMID 22123659.

- 1 2 3 4 Jones B. (2013). The Deerholme Mushroom Book: From Foraging to Feasting. Victoria, British Colombia: TouchWood Editions. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-77151-003-5.

- ↑ Pilz D, McLain R, Alexander S, Villarreal-Ruiz L, Berch S, Wurtz TL, Parks CG, McFarlane E, Baker B, Molina R, Smith JE (2007). Ecology and Management of Morels Harvested From the Forests of Western North America. General Technical Report PNW-GTR-710 (PDF) (Report). Portland, Oregon: United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. p. 4.

- 1 2 3 Loizides M, Alvarado P, Clowez P, Moreau PA, de la Osa LR, Palazón A (2015). "Morchella tridentina, M. rufobrunnea, and M. kakiicolor: a study of three poorly known Mediterranean morels, with nomenclatural updates in section Distantes". Mycological Progress. 14 (3): 1030. doi:10.1007/s11557-015-1030-6.

- 1 2 Davis RM, Sommer R, Menge JA (2012). Field Guide to Mushrooms of Western North America. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 392. ISBN 978-0-520-95360-4.

- ↑ Bone E. (2011). Mycophilia: Revelations from the Weird World of Mushrooms. New York, New York: Rodale. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-60961-987-9.

- ↑ Wood M, Stevens F. "Morchella rufobrunnea". California Fungi. MykoWeb. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ↑ Loizides M, Bellanger J-M, Lowez P, Richard F, Moreau P-A (2016). "Combined phylogenetic and morphological studies of true morels (Pezizales, Ascomycota) in Cyprus reveal significant diversity, including Morchella arbutiphila and M. disparilis spp. nov.". Mycological Progress. 15: 39. doi:10.1007/s11557-016-1180-1.

- ↑ Masaphy S, Zabari L, Goldberg D (2009). "New long-season ecotype of Morchella rufobrunnea from northern Israel" (PDF). Micologia Aplicada International. 21 (2): 45–55. ISSN 1534-2581.

- 1 2 4594809, Ower R, Mills GL, Malachowski JA., "Cultivation of Morchella", published 17 June 1986, assigned to Neogen Corporation

- ↑ States4757640 United States 4757640, Malachowski JA, Mills GL, Ower RD., "Cultivation of Morchella", published 19 July 1988, assigned to Neogen Corporation

- ↑ Stamets P. (2000). Growing Gourmet and Medicinal Mushrooms (3rd ed.). Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. p. 421. ISBN 978-1-58008-175-7.

- ↑ Masaphy S. (2010). "Biotechnology of morel mushrooms: Successful fruiting body formation and development in a soilless system". Biotechnology Letters. 32 (10): 1523–7. doi:10.1007/s10529-010-0328-3. PMID 20563623.

- ↑ Masaphy S. (2005). "External ultrastructure of fruit body initiation in Morchella". Mycological Research. 109 (4): 508–12. doi:10.1017/S0953756204002126. PMID 15912939.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morchella rufobrunnea. |