Monsanto Co. v. Rohm and Haas Co.

| Monsanto Co. v. Rohm and Haas Co. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit |

| Argued | May 3 1971 |

| Decided | January 12 1972 |

| Citation(s) | 456 F.2d 592; 172 U.S.P.Q. (BNA) 323 |

| Holding | |

| That in the Monsanto patent application in question, it did not submit information on of all the testing conducted on the chemical compound. This nondisclosure was considered to be a false representation. The failure to disclose amounted to misrepresentation that transgressed equitable standards of conduct owed the public by Monsanto in return for its monopoly. | |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting | Ruggero J. Aldisert, Francis Lund Van Dusen, and Harry Ellis Kalodner |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Aldisert, joined by Van Dusen |

| Dissent | Kalodner |

Monsanto Co. v. Rohm and Haas Co., 456 F.2d 592 (3d Cir. 1972), is a 1972 decision of the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit interpreting what conduct amounts to fraudulent procurement of a patent. It is one of the early decisions following the Supreme Court's landmark 1964 decision in Walker Process v. Food Machinery holding fraud on the patent office as potentially violating the Sherman Antitrust Act, and one of the first (if not the first) to hold that failure to disclose material information to the Patent Office was fraudulent.

Background

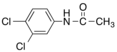

Monsanto procured U.S. Patent No. No. 3,382,280, issued May 7, 1968, having the title 3',4'-dichloropropionanilide (known as 3,4-DCPA or propanil), a herbicide that selectively killed weeds without killing crop plants such as rice.[1] In November 1969 Monsanto sued Rohm and Haas for patent infringement. The only substantial issue was the validity of the patent, and that ultimately turned on whether Monsanto had committed fraud on the Patent Office in procuring the patent.[2]

The application that resulted in the '280 patent was the third of three successive applications, the first two of which were unsuccessful. In the first application, filed in 1957, Monsanto sought a patent on some 100 "compounds, including 3,4-DCPA and 3,4-DCAA (3,4-dichloroacetanilide), a chemical with some similar properties and a similar physical structure. Monsanto claimed that all the members of the class possessed "unusual and valuable herbicidal activity," while related compounds possessed "little or no herbicidal efficiency." Unpersuaded by Monsanto's arguments, the Patent Office rejected the application as unpatentable over the prior art. In 1961, Monsanto filed a new application claiming another large class of compounds, again including 3,4-DCPA and 3,4-DCAA and again asserting that the class possessed "unusual and valuable herbicidal activity." Again, the Patent Office rejected the application as unpatentable over the prior art. In 1967, Monsanto applied again, this time claiming only 3,4-DCPA and representing only that 3,4-DCPA had "unusual and valuable herbicidal activity" and that its activity was "surprising" because "related compounds possess little or no herbicidal efficiency." Again. the Patent Office (initially) rejected the application on the ground that the product was obvious over the prior art. But this time Monsanto overcame the rejection.[3]

A major issue in the Patent Office was whether the patent application should be denied because 3,4-DCPA was obvious from previously known products, the most significant of which was 3,4-DCAA (3,4-dichloroacetanilide), a chemical with some similar properties and a similar physical structure. Both were useful in making pigments and both had herbicidal properties. The structural difference between the two "closely related" compounds was that 3,4-DCAA "differ[ed] in its structural formula solely by having one less CH2 group" than 3,4-DCPA.[4] Because of the similarity in structure between 3,4-DCPA and other chemicals, including 3,4-DCAA, the Patent Office rejected the patent application on obviousness grounds. Monsanto then tried to persuade the Office to withdraw the rejection by submitting documents to show that DCPA was not obvious, because it had greatly superior and unexpected selective herbicidal activity.

Monsanto filed the Husted Affidavit. The trial court found that this document "contains no affirmative misrepresentation and is accurate so far as it goes" but "it is misleading, and was intended to be misleading, in that it fails to state facts known to the applicant which were inconsistent with its position that propanil is a superior herbicide."[5] The court of appeals commented:

The patent was issued, however, . . . after Monsanto submitted an affidavit of Dr. Robert F. Husted, based on tests performed by him on twenty plant species at three different rates of application per acre. The report as presented to the Patent Office asserted that 3,4-DCPA completely killed or severely injured nine of the eleven species and failed to have any effect on only two. Eight other compounds were reported to have no effect on any of the eleven plants and two other compounds, one of them 3,4-DCAA, either had very slight or no effect. Significantly, although the Husted tests entailed tests on twenty species, at three separate rates of application per acre, the Patent Office was informed of tests on only eleven species and only at one rate of application, two pounds per acre. In all, the affidavit showed less than 25 per cent of Husted's results; of 899 tests, only 110 were submitted. The district court concluded that this close-cropping of Husted's findings amounted to misrepresentation.[6]

Under applicable law, as understood by the court, if a compound on which a patent is sought is very similar in structure to a known compound, as 3,4-DCPA and 3,4-DCAA were, a rebuttable presumption arises that the later compound is obvious from the earlier one. "To rebut this presumption it must be shown 'that the claimed compound possesse[d] unobvious or unexpected beneficial properties not actually possessed by the prior art homologue.'"[7]

The Husted Affidavit thus appeared to rebut the obviousness rejection by showing that 3,4-DCPA possessed an unexpected beneficial herbicidal property that 3,4-DCAA and other products lacked. The Husted Affidavit misled the Patent Office, the trial court said, because both 3,4-DCPA and 3,4-DCAA "in fact possess the newly discovered property of the claimed compound."[8]

The trial court said that Monsanto submitted a fraudulent affidavit in that: "It is, in short, composed of half-truths." The court pointed to such omissions as these which made the affidavit one of half-truths:

For example, one omitted test result showed that 3,4-DCAA had a complete kill on pigweed at 2 lbs. per acre of application, just as 3,4-DCPA did. . . . Monsanto, by the Husted affidavit, attempted to show that closely related compounds do not possess unique herbicidal properties. The facts not stated were, therefore material."[9]

The district court held the patent invalid and Monsanto appealed top the Third Circuit.

Decision of Third Circuit

The Third Circuit affirmed the district court's judgment of fraud (2-1) in an opinion by Circuit Judge Aldisert.[10]

Majority opinion

The court looked at the Husted Affidavit in light of its place in the three successive Monsanto patent applications:

In view of Huffman's previously unsuccessful attempts to obtain a patent, it is reasonable to conclude that his success with his 1968 application, originally rejected by the examiner, and later accepted after presentation of the Husted Report, was attributed to his emphasis that the compound possessed properties of 'surprising . . . herbicidal efficiency' not possessed by related compounds.[11]

Whether 3,4-DCPA really was surprisingly superior to related compounds as a herbicide was therefore critical to the patent prosecution and to whether Monsanto had committed fraud on the Patent Office. The court rejected Monsanto's argument that in the affidavit it was merely putting its best foot forward:

The Husted affidavit to the Patent Office did not nearly reflect the total Husted test as transmitted to Huffman. Indeed, an examination of the report permits, if not compels, the misleading inference that it constituted a complete and accurate analysis of all the testing instead of an edited version thereof. Concealment and nondisclosure may be evidence of and equivalent to a false representation, because the concealment or suppression is, in effect, a representation that what is disclosed is the whole truth.[12]

Looking at this pattern of conduct, the court said, "[W]e cannot bring ourselves to say that the application for the 1968 patent displayed that standard of conduct demanded under the circumstances." Rather, "Monsanto was obliged to disclose more information as to the herbicidal properties of related compounds to the Patent Office than it did." The reason is that "what is at issue is not merely a contest between the parties but a public interest" that spurious patents should not issue. As a result of Monsanto's truncated disclosure of the facts concerning 3,4-DCPA's comparative efficacy as a herbicide, "it was impossible for the Patent Office fairly to assess Monsanto's application against the prevailing statutory criteria."[13]

The court concluded:

Thus, Monsanto's failure to disclose amounted to misrepresentation transgressing equitable standards of conduct owed the public by the applicant in return for its monopoly. Accordingly, Monsanto was not entitled to the patent monopoly, and the district court did not err in [invalidating the patent].[14]

Dissent

Judge Kalodner dissented. First, he said, the majority decided the case on the basis of the preponderance of evidence but it should have used the "clear and convincing evidence" standard.[15]

Second, the district court erroneously said that it was not necessary to prove specific intent to deceive the Patent Office "when there is evidence of a deliberate withholding of material information," and that the patent must be rejected "even if the decision not to disclose was motivated by nothing more than bad judgment as to the materiality of the information."[16]

Third, it was not shown that the Patent Office "would not have issued the patent but for the claimed fraudulent conduct." There was no proof that the Patent Office was misled.[17]

Commentary

In an article in the George Washington Law Review, Irving Kayton criticized "the Third Circuit's ignorance of the accepted manner and practice, defined by statute and rule, in which patent prosecution takes place."[18] Kayton said that it was the responsibility of the patent examiner to review the records of the earlier stages of the patent prosecution, and there is a legal presumption that the examiner did that; that examination would have disclosed the information that Monsanto withheld in the Husted Affidavit. Accordingly, Kayton argued, "Monsanto['s] patent solicitor was thus completely justified in attributing actual, but at the least, constructive knowledge to the examiner of the contents of the disclosures of both the 1961 and 1957 applications."[19] Co-author Richard H. Stern disagreed with his colleague on this issue. Stern maintained, "The proposed reliance on constructive knowledge, and the indulgence in legal fictions and presumptions that follows, has far more flavor of a determination not to learn damaging facts than it has of the candor required in such cases."[20]

Moreover, argued Kayton, the fact that the Third Circuit and the judge in the similar Texas case disagreed over whether Monsanto was just "putting its best foot forward" or instead was intentionally defrauding the Patent Office indicates that reasonable men can differ: "This being so, is it not an inescapable conclusion . . . that the Monsanto patent solicitor's [conduct] . . . was at worst a nonculpable mistake of judgment?"[21] Again, co-author Stern disagreed: "No. The Third Circuit, on the contrary, appears to have thought that Judge Singleton's views were plainly erroneous, and that his acceptance of the patentee's theory that 'it is all right to put your best foot forward with the Patent Office' was contrary to the legal standard as to candor required in ex parte proceedings of this type. Given so thoroughly erroneous a concept of the standard of candor, it is neither surprising that in the circumstances of this case the judge using that legal standard found no fraud nor surprising that the judges rejecting it found fraud."[22]

Another discussion of this case faults the district court's decision for purporting to invalidate the patent for fraud, and by implication the subsequent Third Circuit affirmance. The stated basis of the criticism is that fraudulent procurement does not invalidate a patent, but merely makes it permanently unenforceable.[23]

References

| The citations in this Article are written in Bluebook style. Please see the Talk page for this Article. |

- ↑ With an estimated use of about 8 million pounds in 2001, propanil is one of the more widely used herbicides in the United States. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2000-2001 Pesticide Market Estimates.

- ↑ Monsanto Co. v. Rohm & Haas Co., 456 F.2d 592, 596 (3d Cir. 1972) ("In the view we take, it becomes necessary to reach only the misrepresentation issue.").

- ↑ 456 F.2d at 596.

- ↑ 456 F.2d at 596. Such pairs of compounds are termed "adjacent homologues" and they are known to have similar chemical and physical properties. See article homologous series. See also In re Henze, 181 F.2d 196, 201 (CCPA 1950), in which the court stated, "In effect, the nature of homologues and the close relationship the physical and chemical properties of one member of a series bears to adjacent members is such that a presumption of unpatentability arises against a claim directed to a composition of matter, the adjacent homologue of which is old in the art."

- ↑ Monsanto Co. v. Rohm and Haas Co., 312 F. Supp. 778, 791 (E.D. Pa. 1970)

- ↑ 456 F.2d at 596-97.

- ↑ 312 F. Supp. at 789. The court said that the reason for this rule is that "the characteristics normally possessed by members of a homologous series are principally the same, and vary but gradually from member to member. Chemists knowing the properties of one member of a series would in general know what to expect in adjacent members." Id. at 790.

- ↑ 312 F. Supp. at 790.

- ↑ 312 F.Supp. 791-92.

- ↑ 456 F.2d 592 (3d Cir. 1972).

- ↑ 456 F.2d at 599.

- ↑ 456 F.2d at 599. The Third Circuit noted but rejected the conclusion of a Texas district court that addressed these issues in Monsanto v. Dawson Chemical Corp., 312 F.Supp. 452 (S.D. Tex. 1970). The Third Circuit said: "We do not find persuasive that court's treatment of the misrepresentation issue or its conclusion that Monsanto 'did nothing more than put their best foot forward.' " 456 F.2d at 597 n.4 (quoting 312 F. Supp. at 463).

- ↑ 456 F.2d at 600.

- ↑ 456 F.2d at 600-01.

- ↑ The majority opinion took issue with this assertion, which was based with a colloquy with counsel. The trial court's conclusions of law stated that "[u]pon our examination of the record, we have concluded that Rohm and Haas has met its burden of proving invalidity by clear and convincing proof." 456 F.2d at 601 n.14 (quoting 312 F.Supp. at 797).

- ↑ The majority opinion took issue with this assertion, pointing out that it was an alternative holding and that the district court's statement in full was, " 'Even if we were persuaded to change our mind' and find that 'Monsanto did not intend to mislead, . . . a specific intent to deceive is not necessary where there is evidence of deliberate withholding of material information' " 456 F.2d at 601 n.14.

- ↑ 456 F.2d 603-04.

- ↑ Irving Kayton, John F. Lynch, Richard H. Stern, Fraud in Patent Procurement: Genuine and Sham Charges, 43 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1, 99 (1974).

- ↑ Id. at 100.

- ↑ Id. at 100 n.*.

- ↑ Id. at 99.

- ↑ Id at 99 n.*.

- ↑ See Donald R. Dunner, James B, Gambrell, and Irving Kayton, Patent Law (1969-70), in [1970] Ann. Surv. Am. L. 395, 425 n.140 (1970).