Mersenne's laws

If the tension on a string is ten lbs., it must be increased to 40 lbs. for a pitch an octave higher.[1]

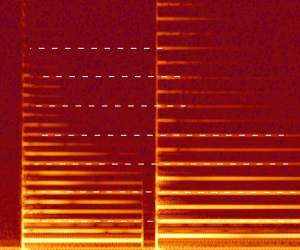

Mersenne's laws are laws describing the frequency of oscillation of a stretched string or monochord,[1] useful in musical tuning and musical instrument construction. The equation was first proposed by French mathematician and music theorist Marin Mersenne in his 1637 work Traité de l'harmonie universelle.[2] Mersenne's laws govern the construction and operation of string instruments, pianos, harps, which must accommodate the total tension force required to keep the strings at the proper pitch. Lower strings are thicker, thus having a greater mass per unit length. They typically have lower tension. Higher-pitched strings typically are thinner, have higher tension, and may be shorter. "This result does not differ substantially from Galileo's, yet it is rightly known as Mersenne's law," because Mersenne physically proved their truth through experiments (while Galileo considered their proof impossible).[3] "Mersenne investigated and refined these relationships by experiment but did not himself originate them".[4]

Equations

The fundamental frequency is:

- a) Inversely proportional to the length of the string (the law of Pythagoras[1]),

- b) Proportional to the square root of the stretching force, and

- c) Inversely proportional to the square root of the mass per unit length.

- (equation 26)

- (equation 27)

- (equation 28)

Thus, for example, all other properties of the string being equal, to make the note one octave higher (2/1) one would need either to decrease its length by half (1/2), to increase the tension to the square (4), or to decrease its mass per unit length by the inverse square (1/4).

| Harmonics | Length, | Tension, | or Mass |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 1/2 = 0.5 | 2² = 4 | 1/2² = 0.25 |

| 3 | 1/3 = 0.33 | 3² = 9 | 1/3² = 0.11 |

| 4 | 1/4 = 0.25 | 4² = 16 | 1/4² = 0.0625 |

| 8 | 1/8 = 0.125 | 8² = 64 | 1/8² = 0.015625 |

These laws are derived from Mersenne's equation 22:[5]

The formula for the fundamental frequency is:

where f is the frequency, L is the length, F is the force and μ is the mass per unit length.

Similar laws were not developed for pipes and wind instruments at the same time since Mersenne's laws predate the conception of wind instrument pitch being dependent on longitudinal waves rather than "percussion".[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Jeans, James Hopwood (1937/1968). Science & Music, p.62-4. Dover. ISBN 0-486-61964-8. Cited in "Mersenne's Laws", Wolfram.com

- ↑ Mersenne, Marin (1637). Traité de l'harmonie universelle, . via the Bavarian State Library. Cited in "Mersenne's Laws", Wolfram.com.

- 1 2 Cohen, H.F. (2013). Quantifying Music: The Science of Music at the First Stage of Scientific Revolution 1580–1650, p.101. Springer. ISBN 9789401576864.

- ↑ Gozza, Paolo; ed. (2013). Number to Sound: The Musical Way to the Scientific Revolution, p.279. Springer. ISBN 9789401595780. Gozza is referring to statements by Sigalia Dostrovsky's "Early Vibration Theory", p.185-187.

- ↑ Steinhaus, Hugo (1999). Mathematical Snapshots, . Dover, ISBN 9780486409146. Cited in "Mersenne's Laws", Wolfram.com.